Estatism, Escapism, and Inhabiting the Inhibitive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prison Education in England and Wales. (2Nd Revised Edition)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 388 842 CE 070 238 AUTHOR Ripley, Paul TITLE Prison Education in England and Wales. (2nd Revised Edition). Mendip Papers MP 022. INSTITUTION Staff Coll., Bristol (England). PUB DATE 93 NOTE 30p. AVAILABLE FROMStaff College, Coombe Lodge, Blagdon, Bristol BS18 6RG, England, United Kingdom (2.50 British pounds). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Correctional Education; *Correctional Institutions; Correctional Rehabilitation; Criminals; *Educational History; Foreign Countries; Postsecondary Education; Prisoners; Prison Libraries; Rehabilitation Programs; Secondary Education; Vocational Rehabilitation IDENTIFIERS *England; *Wales ABSTRACT In response to prison disturbances in England and Wales in the late 1980s, the education program for prisoners was improved and more prisoners were given access to educational services. Although education is a relatively new phenomenon in the English and Welsh penal system, by the 20th century, education had become an integral part of prison life. It served partly as a control mechanism and partly for more altruistic needs. Until 1993 the management and delivery of education and training in prisons was carried out by local education authority staff. Since that time, the education responsibility has been contracted out to organizations such as the Staff College, other universities, and private training organizations. Various policy implications were resolved in order to allow these organizations to provide prison education. Today, prison education programs are probably the most comprehensive of any found in the country. They may range from literacy education to postgraduate study, with students ranging in age from 15 to over 65. The curriculum focuses on social and life skills. -

165/Diciembre/2017 Ejemplar Gratuito

revista sobre programación de plataformas de televisión de pago en españa 165/diciembre/2017 ejemplar gratuito knightfall hbo book diciembre2017 una publicación de www.neeo.es Sony Pictures Television Networks Iberia, S.L. Turner Broadcasting System España The Walt Disney Company Iberia Discovery Networks International Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia AMC Networks International | Iberia NBC Universal Global Networks España Viacom International Media Networks Fox Networks Group España neeo no se responsabiliza de los DTS Distribuidora de Televisión Digital posibles cambios que puedan Netflix España realizar los diversos canales en su TV5Monde programación. HBO España Amazon.com, Inc Ejemplar gratuito. TV5Monde cine y series infantil deportes amazon prime video canal panda eurosport 1 amc nickedoleon eurosport 2 axn canal hollywood documentales música comedy central a&e sol música cosmo cazavisión vh1 dark crimen + investigación fox discovery channel hbo españa historia movistar cine nat geo wild movistar series national geographic movistar series xtra odisea movistar xtra mtv netflix extra somos canal cocina sundancetv decasa tcm tnt xtrm book cine series book amazon prime video HD amazon.com, inc. Jean-Claude Van Johnson Jean-Claude Van Damme no muestra ninguna piedad y tampoco hace prisioneros en el nuevo tráiler de la última serie de Amazon Original Jean-Claude Van Johnson que aúna acción y humor. Si necesitas eliminar a un rival político, debilitar a una corporación multinacional o derrocar al gobierno, y quieres hacerlo con la máxima discreción, sólo hay una persona que puede ayudarte: una de las estrellas de cine más reconocidas internacionalmente. Jean-Claude Van Johnson está protagonizada por Jean-Claude Van Damme (JCVD) que interpreta a “Jean-Claude Van Johnson” un reconocido maestro de artes marciales y un auténtico fenómeno en el mundo del cine que, además bajo el nombre de “Johnson” trabaja de manera encubierta como unos de los mercenarios más peligrosos del mundo. -

British TV Streaming Guide

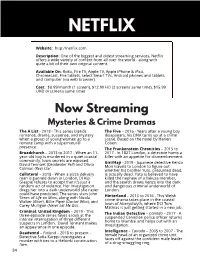

NETFLIX Website: http://netflix.com Description: One of the biggest and oldest streaming services, Netflix offers a wide variety of content from all over the world - along with quite a bit of their own original content. Available On: Roku, Fire TV, Apple TV, Apple iPhone & iPad, Chromecast, Fire tablets, select Smart TVs, Android phones and tablets, and computer (via web browser). Cost: $8.99/month (1 screen), $12.99 HD (2 screens same time), $15.99 UHD (4 screens same time) Now Streaming Mysteries & Crime Dramas The A List - 2018 - This series blends The Five – 2016 - Years after a young boy romance, drama, suspense, and mystery disappears, his DNA turns up at a crime when a group of young women go to a scene. Based on the novel by Harlen remote camp with a supernatural Coben. presence. The Frankenstein Chronicles – 2015 to Broadchurch – 2013 to 2017 - When an 11- 2017 - In 1827 London, a detective hunts a year-old boy is murdered in a quiet coastal killer with an appetite for dismemberment. community, town secrets are exposed. Giri/Haji - 2019 - Japanese detective Kenzo David Tennant (Deadwater Fell) and Olivia Mori travels to London to figure out Colman (Rev) star. whether his brother Yuto, presumed dead, Collateral – 2018 - When a pizza delivery is actually dead. Yuto is believed to have man is gunned down in London, DI Kip killed the nephew of a Yakuza member, Glaspie refuses to accept that it's just a and the search draws Kenzo into the dark random act of violence. Her investigation and dangerous criminal underworld of drags her into a dark underworld she never London. -

Statewatch Bulletin Vol 6 No 4, July-August 1996

Statewatch bulletin and strong pressure from the US government. Vol 6 no 4, July-August 1996 Philippino president, Mr Fidel Ramos, recently called upon Dr Sison to return to his country, IMMIGRATION & ASYLUM promising that he would be safe there, but human rights organizations have warned that the communist SWEDEN leader would risk being killed at the hands of death France admits wrong man named squads. There is still an unofficial price on his head of one million pesos, dead or alive. Mr Ramos was The French Security Police have now admitted that responsible for the nine-year detention and repeated the Algerian citizen Abdelkrim Deneche had been torture of Dr Sison under the Marcos government wrongly named as responsible for the bomb attack at between 1977 and 1986. the Paris Saint-Michel metro station 25 July last year. Dutch legal experts have expressed their disbelief He had been mistaken for the another person, Ait and criticism about the government's position, calling Touchent, called Tarek. the present decision "insane" and "a text riddled with When the French authorities asked for the beginner's mistakes". They have pointed out that extradition of Deneche in 1995, based on an eye- there is no solid ground for the accusation of witness statement by a French policeman, the "terrorist activities", an argument also put forward by Swedish Supreme Court found that there was the Raad van State, and that in the Philippines itself, conclusive evidence that Deneche was innocent (see there is no outstanding warrant against Dr Sison. The Statewatch, vol 5 no 6). -

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

Media Nations 2020 UK Report

Media Nations 2020 UK report Published 5 August 2020 Contents Section Overview 3 1. Covid-19 media trends: consumer behaviour 6 2. Covid-19 media trends: industry impact and response 44 3. Production trends 78 4. Advertising trends 90 2 Media Nations 2020 Overview This is Ofcom’s third annual Media Nations, a research report for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. It reviews key trends in the TV and online video sectors, as well as radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this report is an interactive report that includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. This year’s publication comes during a particularly eventful and challenging period for the UK media industry. The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown period has changed consumer behaviour significantly and caused disruption across broadcasting, production, advertising and other related sectors. Our report focuses in large part on these recent developments and their implications for the future. It sets them against the backdrop of longer-term trends, as laid out in our five-year review of public service broadcasting (PSB) published in February, part of our Small Screen: Big Debate review of public service media. Media Nations provides further evidence to inform this, as well as assessing the broader industry landscape. We have therefore dedicated two chapters of this report to analysis of Covid-19 media trends, and two chapters to wider market dynamics in key areas that are shaping the industry: • The consumer behaviour chapter examines the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on media consumption trends across television and online video, and radio and online audio. -

The Good Prison.Pdf

Gerard Lemos was described by Community Care magazine as ‘one of the UK’s leading thinkers on social policy’. His previous books include The End of the Chinese Dream: Why Chinese people fear the future published by Yale University Press and The Communities We Have Lost and Can Regain (with Michael Young). He has held many public appointments including as a Non-Executive Director of the Crown Prosecution Service. First published in 2014 Lemos&Crane 64 Highgate High Street, London N6 5HX www.lemosandcrane.co.uk All rights reserved. Copyright ©Lemos&Crane 2014 The right of Gerard Lemos to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 978-1-898001-75-1 Designed by Tom Keates/Mick Keates Design Printed by Parish Print Consultants Limited To navigate this PDF, click on the chapter headings below, you can return to the table of contents by clicking the return icon Contents Foreword vii Introduction 8 Part One : Crime and Society 15 1. Conscience, family and community 15 2. Failure of conscience in childhood and early family experiences of offenders 26 3. The search for punishment 45 4. A transformed social consensus on crime and punishment since the 1970s 56 5. Justice and restoration 78 Part Two: The Good Prison 92 6. Managing the Good Prison 92 7. Family life of prisoners and opportunities for empathy 110 8. Mindfulness: reflection and collaboration 132 9. Creativity and artistic activity 159 10. -

European High-End Fiction Series. State of Play and Trends

European high-end fiction series: State of play and trends This report was prepared with the support of the Creative Europe programme of the European Union. If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication, please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. The analysis presented in this publication cannot in any way be considered as representing the point of view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. European high-end fiction series: State of play and trends Gilles Fontaine Marta Jiménez Pumares Table of contents Executive summary .................................................................................................. 1 Scope and methodology .......................................................................................... 5 1. Setting the scene in figures ............................................................................. 8 1.1. The production of high-end fiction series in the European Union .................................................................... 8 1.1.1. The UK is the primary producer of high-end series in Europe ................................................... 10 1.1.2. International co-productions: small but growing .......................................................................... -

Too Close for Comfort: Direct Address and the Affective Pull of the Confessional Comic Woman in Chewing Gum and Fleabag

Too close for comfort: direct address and the affective pull of the confessional comic woman in Chewing Gum and Fleabag Article Accepted Version Woods, F. (2019) Too close for comfort: direct address and the affective pull of the confessional comic woman in Chewing Gum and Fleabag. Communication, Culture and Critique, 12 (2). pp. 194-212. ISSN 1753-9129 doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz014 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/81363/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz014 Publisher: Oxford University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Too Close for Comfort: Direct address and the affective pull of the confessional comic woman in Chewing Gum and Fleabag. Abstract The 2010s saw a boom in television comedies, created by, written, and starring women, that exploring the bawdy and chaotic lives of protagonists who were experiencing some form of arrested development. These comedies sought to build intimate connections with their imagined audiences by crossing boundaries — social, bodily and physical — to produce comedies of discomfort. Drawing in part on Rebecca Wanzo’s consideration of ‘precarious-girl comedy’ (2016) I examine how two British television comedies intensified these intimate connections through the use of direct address, binding the audience tightly to the sexual and social misadventures of their twenty-something female protagonists. -

(IN)VISIBLE ENTREPRENEURS: CREATIVE ENTERPRISE in the URBAN MUSIC ECONOMY Joy White

(IN)VISIBLE ENTREPRENEURS: CREATIVE ENTERPRISE IN THE URBAN MUSIC ECONOMY Joy White A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. Signed: Signed: Dated: June 2014 ! "" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the unwavering support of my supervisors, Dr Gauti Sigthorsson and Dr Stephen Kennedy. In particular, for letting me know that this research project had value and that it was a worthwhile object of study. Also, Dawn, Maxine, Dean and Alvin who proofread the final drafts - without complaining and resisted the temptation to ask whether I’d finished it yet. Lindsey and Gamze, for their encouragement and support throughout all of the economic and social ups and downs during the life of this project. My mum, Ivaline White whose three-week journey in 1954 from Jamaica to London provided the foundation, and gave me the courage, to start and to finish this. My daughter Karis, who once she had embraced her position as a ‘PhD orphan’, grew up with the project, accompanied me while I presented at an academic conference in Turkey, matured and evolved into an able research assistant, drawing my attention to significant events, music and debates. -

HUMANE JUSTICE What Role Do Kindness, Hope and Compassion Play in the Criminal Justice System?

The Monument Fellowship HUMANE JUSTICE What role do kindness, hope and compassion play in the criminal justice system? Edited by LISA ROWLES & IMAN HAJI “Kindness has a vital role to play in our society, and none more so than in our prison system. For those who have failed to live a normal law-abiding life, we need kindness to be at the forefront of their prison experience. Kindness from prison officers, nurses, probation officers and fellow inmates will help produce the fellow citizen who embraces society, not fights against it. As this book clearly demonstrates, the kinder a prison system is, the more successful it will be.” James Timpson. Chief Executive, Timpson Group “The Monument Fellowship has assembled a fascinating and varied array of perspectives from informed contributors on the role of compassion and kindness in addressing injustice. Covid-19 has shone a spotlight on many of these injustices and this collection provides a positive, evidence based and hopeful road map for how we can move forwards.” Frances Mapstone, acting CEO of Just for Kids Law “This book, with its focus on the role of kindness, hope and compassion within the criminal justice system, is set to be a wonderful portfolio of optimism, insight and expertise. It enables an amplification of the voices of those most affected by it – the people subject to its rules and restrictions, the people responsible for their care, and those with an interest in its reform and effectiveness. Through its broad diversity of contributors and media, the book is sure to demonstrate that a bright light exists in the dark corners of our society. -

Billy Rivista Di Cinema E Altre Perversioni Il Contagio

E ALTRE PERVERSIONI E ALTRE DICINEMA RIVISTA BILLY FREE PRESS CRONACHE DICONTAMINAZIONIARTISTICHE IL CONTAGIO marzo/1.20 MARCO BACCHI, LEANDRA BORSCI, Ramiro Castro Xiques, NOEMI GIUGLIANO, Francesca Leoni, MATTEO LOLLETTI, Davide Mastrangelo, PIERO MEROLA, MARCO MULANA, PAOLO UTILI. INDICE Il contagio 3 CITAZIONE Germano Celant 4 LO STATO DELL’ARTE «Oggi l’arte si fa con tutto Leandra Borsci Cronache di contaminazioni artistiche di contaminazioni Cronache 6 LE CITTÀ INVIVIBILI e ovunque, senza confini Ramiro Castro Xiques 8 IL “BISOGNO” DEL CONTAGIO: linguistici e territoriali. BREVE EXCURSUS NEL CINEMA DEL 2000 Paolo Utili Gli artisti entrano e agiscono 10 PETER GREENAWAY, L’ARTISTA CONTAMINATO Noemi Giugliano nel campo dell’immagine 12 IL DOCUMENTARIO COME FINZIONE DEL REALE con un’attitudine leggera Marco Bacchi 14 NOI SIAMO PAROLA e plurale, Matteo Lolletti 17 LA LINGUA BATTE DOVE VUOLE muovendosi senza istanze Leandra Borsci 20 SUA ALTEZZA REAL(TÀ) Marco Mulana univoche nella panoramica 22 NUOVE CONTAMINAZIONI MUSICALI: LA “BLACK DIASPORA” È IL FUTURO di tutti i media». DELLA SCENA BRITANNICA Piero Merola Germano Celant 24 VIDEOARTE > ARTI INTERMEDIALI Francesca Leoni e Davide Mastrangelo 26 CRUCIVIRUS Mulangella 3 LO STATO DELL’ARTE Il contagio Abbiamo scritto, riscritto, riformulato, disfatto e Ma abbiamo portato avanti le nostre istanze, i nostri reinterpretato questo editoriale rincorrendo l’attua- pensieri, le nostre battute sulla tastiera con maggio- artistiche di contaminazioni Cronache lità più recente, troppo sfuggente e troppo poco pre- re enfasi quando la cultura è venuta in soccorso come dicibile. Quando ragionavamo su questo primo numero di anticorpo per riempire il silenzio dell’isolamento da BILLY di quello che si sarebbe da lì a poco rivelato un COVID-19.