Chapter Thirteen Ariadne, a Social Art Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protest » Video- Collage

FemLink, the International Videos-Collage LIST OF VIDEOS in THE « PROTEST » VIDEO- COLLAGE 26 videos - 50 min. The videos inccluded in the collage was created for FemLink 01 - IT’S JUST A GAME, Maria Rosa Jijon (Ecuador) The word Game is indeed a trap: not only translates into play but, above all, in prey. In an era apparently facilitated by the invasion of computers and machines, the reality is that everything looks, more and more, like the locations of Orwell’s 1984. The removal of spatio- temporal boundaries is just a consolation prize, because the customs continue to exist and overcome them is always crooked at least as to live as emigrants once exceeded. Ilaria Giordano Drome Magazine CREDITS : Music: Mario Bross 02 - OVERFLOW. A NOTE OF SUICIDE, Sara Malinarich (Chile) A woman sacrifices herself in a technological scene, in front of virtual witnesses and streets coexisting in time in different places. The screen is the suicide note, the physical support of a protest that overflows through an invisible mechanics that activates the self-destruction sequence. It is the suicide note that burns and sets fire to the woman, becoming the bonfire of her protests. 'Overflow' is a videocreation made in real-time with automated machines and telepresence systems (and a veiled tribute to José Val del Omar.) Credits: Cast: CAROLINA PRIEGO. Technical Management: MANUEL TERÁN. Photography: MAKU LÓPEZ. Edition, Postproduction & Graphics: JORGE RUIZ ABÁNADES. 3D Motion: FRANÇOIS MOURRE. Music: EN BUSCA DEL PASTO Note: The audio of this piece is in Dia-phonic system, created by José Val del Omar in 1944. -

High Performance Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5p30369v Online items available Finding aid for the magazine records, 1953-2005 Finding aid for the magazine 2006.M.8 1 records, 1953-2005 Descriptive Summary Title: High Performance magazine records Date (inclusive): 1953-2005 Number: 2006.M.8 Creator/Collector: High Performance Physical Description: 216.1 Linear Feet(318 boxes, 29 flatfile folders, 1 roll) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: High Performance magazine records document the publication's content, editorial process and administrative history during its quarterly run from 1978-1997. Founded as a magazine covering performance art, the publication gradually shifted editorial focus first to include all new and experimental art, and then to activism and community-based art. Due to its extensive compilation of artist files, the archive provides comprehensive documentation of the progressive art world from the late 1970s to the late 1990s. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Linda Burnham, a public relations officer at University of California, Irvine, borrowed $2,000 from the university credit union in 1977, and in a move she described as "impulsive," started High -

Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 Contents

Henriette Huldisch Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 Contents 5 Director’s Foreword 9 Acknowledgments 13 Before and Besides Projection: Notes on Video Sculpture, 1974–1995 Henriette Huldisch Artist Entries Emily Watlington 57 Dara Birnbaum 81 Tony Oursler 61 Ernst Caramelle 85 Nam June Paik 65 Takahiko Iimura 89 Friederike Pezold 69 Shigeko Kubota 93 Adrian Piper 73 Mary Lucier 97 Diana Thater 77 Muntadas 101 Maria Vedder 121 Time Turned into Space: Some Aspects of Video Sculpture Edith Decker-Phillips 135 List of Works 138 Contributors 140 Lenders to the Exhibition 141 MIT List Visual Arts Center 5 Director’s Foreword It is not news that today screens occupy a vast amount of our time. Nor is it news that screens have not always been so pervasive. Some readers will remember a time when screens did not accompany our every move, while others were literally greeted with the flash of a digital cam- era at the moment they were born. Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 showcases a generation of artists who engaged with monitors as sculptural objects before they were replaced by video projectors in the gallery and long before we carried them in our pockets. Curator Henriette Huldisch has brought together works by Dara Birnbaum, Ernst Caramelle, Takahiko Iimura, Shigeko Kubota, Mary Lucier, Muntadas, Tony Oursler, Nam June Paik, Friederike Pezold, Adrian Piper, Diana Thater, and Maria Vedder to consider the ways in which artists have used the monitor conceptually and aesthetically. Despite their innovative experimentation and per- sistent relevance, many of the sculptures in this exhibition have not been seen for some time—take, for example, Shigeko Kubota’s River (1979–81), which was part of the 1983 Whitney Biennial but has been in storage for decades. -

Nancy Buchanan Consumption

NANCY BUCHANAN CONSUMPTION ).'82/+0'3+9-'22+8? NANCY BUCHANAN CONSUMPTION Charlie James Gallery is delighted to present Consumption, Buchanan has collaborated with Carolyn Potter to make our first solo show with Los Angeles-based artist Nancy miniatures incorporating video. In American Dream #6, Buchanan. their very first piece together, every surface is littered with home improvement brochures while on the small TV Joe Intending to focus on painting at UC Irvine, Nancy McCarthy is shouting, and bundled newspapers trace the Buchanan’s (b. 1946, Boston, MA) conceptual bent started history of atomic weapons. Another miniature – Use Value when she was a student of Robert Irwin. Absorbing his celebrates the local economies of garage sales. lesson that art is an experience rather than an object, she extended her production to unusual materials (shredded Buchanan will donate 50% of the proceeds of her sales from newspaper, human hair) and methods of presentation. the 50 Shades of Cake series to the LAMP organization Buchanan works across drawing, performance, video, collage, (begun in 1985 as Los Angeles Men’s Place) that assists mixed media work and installation. As she embraces the homeless people in and around Skid Row. notion that art should evidence the time of its making, Buchanan’s pieces often address social and political Beginning with her participation as a founding member of issues. F Space Gallery in Costa Mesa, Nancy Buchanan has been involved in numerous artists’ groups including The Los “Consumption” was the 19th-century name for tuberculosis, Angeles Woman’s Building and Los Angeles Contemporary from the Latin root con (completely) plus sumere (to take Exhibitions (LACE); she has also acted as curator for up from under), a disease Buchanan suffered from as a young several exhibitions and projects. -

25 Years of Ars Electronica

Literature: Winners in the film section – Computer Animation – Visual Effects Literature: Literature : Literature: Literature (2) : Literature: Literature (2) : Blick, Stimme und (k)ein Körper – Der Einsatz 1987: John Lasseter, Mario Canali, Rolf Herken Cyber Society – Mythos und Realität der Maschinen, Medien, Performances – Theater an Future cinema !! / Jeffrey Shaw, Peter Weibel Ed. Gary Hill / Selected Works Soundcultures – Über elektronische und digitale Kunst als Sendung – Von der Telegrafie zum der elektronischen Medien im Theater und in 1988: John Lasseter, Peter Weibel, Mario Canali and Honorary Mentions (right) Informationsgesellschaft / Achim Bühl der Schnittstelle zu digitalen Welten / Kunst und Video / Bettina Gruber, Maria Vedder Intermedialität – Das System Peter Greenaway Musik / Ed. Marcus S. Kleiner, A. Szepanski 25 years of ars electronica Internet / Dieter Daniels VideoKunst / Gerda Lampalzer interaktiven Installationen / Mona Sarkis Tausend Welten – Die Auflösung der Gesellschaft Martina Leeker (Ed.) Yvonne Spielmann Resonanzen – Aspekte der Klangkunst / 1989: Joan Staveley, Amkraut & Girard, Simon Wachsmuth, Zdzislaw Pokutycki, Flavia Alman, Mario Canali, Interferenzen IV (on radio art) Liveness / Philip Auslander im digitalen Zeitalter / Uwe Jean Heuser Perform or else – from discipline to performance Videokunst in Deutschland 1963 – 1982 Arquitecturanimación / F. Massad, A.G. Yeste Ed. Bernd Schulz John Lasseter, Peter Conn, Eihachiro Nakamae, Edward Zajec, Franc Curk, Jasdan Joerges, Xavier Nicolas, TRANSIT #2 -

Barbara T. Smith Coffin Series and Related Material, 1965-1967

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8st7rjv Online items available Finding aid for the Barbara T. Smith Coffin series and related material, 1965-1967 Isabella Zuralski Finding aid for the Barbara T. 2013.M.23 1 Smith Coffin series and related material, 1965-1967 Descriptive Summary Title: Barbara T. Smith Coffin series and related material Date (inclusive): 1965-1967 Number: 2013.M.23 Creator/Collector: Smith, Barbara Turner, 1931- Physical Description: 12.26 Linear Feet(16 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The collection comprises Coffin, a unique set of twenty-five hand-bound artist's books documenting Barbara T. Smith's experiments with an early Xerox 914 copy machine, and a set of working materials and other works related to the Coffin series. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical / Historical Note Barbara T. Smith, a pioneer in performance and body art, was born in Pasadena, California in 1931. She studied painting, art history and religion at Pomona College, graduating in 1953. In 1965, she began to study at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, and in 1971, she received her MFA from the University of California, Irvine. While attending UC Irvine, she founded, together with Nancy Buchanan and Chris Burden, the student-run experimental art gallery F-Space. -

A Performing Archive 17.02.17, 10�14

re.act.feminism - a performing archive 17.02.17, 1014 Search A Ebtisam Abdulaziz Marina Abramović Helena Almeida Eleanor Antin Arahmaiani Malin Arnell Oreet Ashery Augusta Atla Margarita Azurdia B Back to selection Antonia Baehr Complete Archive Maja Bajević Manon, La dame au crâne rasé, 1970s Anne Bean Anat Ben-David Renate Bertlmann Manon Document media Pauline Boudry & Das lachsfarbene Boudoir / La dame au crâne video, colour, sound, 12:10 min Renate Lorenz rasé Issue date Nisrine Boukhari 1974, 1978 / 2006 After studying commercial art and acting in Zurich, in 1974 Marijs Boulogne Tags Manon (*1946, Switzerland) began creating environments in Tania Bruguera beauty, fashion/glamour, which she plays different roles together with sometimes as femininity, in/visibility, Nancy Buchanan many as 60 extras and uses virtually all forms of modern private/public Maris Bustamante media. She was one of Switzerland’s first performance artists About the project C Archive Signature Partners and is most likely the country’s most famous. She lived in Paris MAN 1 Cabello / Carceller Imprint from 1977 to 1980 before moving back to Zurich, where she lives Shirley Cameron/ Contact and works today. Since 1998, she has been concentrating Monica Ross/ Find us on facebook mainly on installations which explore eroticism and transience, Evelyn Silver most recently in 2011 in her project "Hotel Dolores" concerned Graciela Carnevale with deserted spa hotels in the spa district of Baden, Aargau Theresa Hak Kyung (Switzerland). Cha Helen Chadwick This is a collection of TV features about, among other works, Manon’s Das lachsfarbene Boudoir (The Salmon-Coloured Chicks on Speed Boudoir), her first environment which she reconstructed for the Lygia Clark Migros Museum Zurich in 2006, and La dame au crâne rasé (The Mary Coble Woman with the Shaved Head), a series of staged photographs Colette in Paris. -

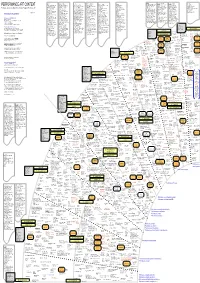

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012 Jan 23)

OTIS Ben Maltz Gallery WB Exhibition Checklist 1 | Page of 58 (2012_Jan_23) GUIDE TO THE EXHIBITION Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011–January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design Introduction “Doin’ It in Public” documents a radical and fruitful period of art made by women at the Woman’s Building—a place described by Sondra Hale as “the first independent feminist cultural institution in the world.” The exhibition, two‐volume publication, website, video herstories, timeline, bibliography, performances, and educational programming offer accounts of the collaborations, performances, and courses conceived and conducted at the Woman’s Building (WB) and reflect on the nonprofit organization’s significant impact on the development of art and literature in Los Angeles between 1973 and 1991. The WB was founded in downtown Los Angeles in fall 1973 by artist Judy Chicago, art historian Arlene Raven, and designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville as a public center for women’s culture with art galleries, classrooms, workshops, performance spaces, bookstore, travel agency, and café. At the time, it was described in promotional materials as “a special place where women can learn, work, explore, develop their own point of view and share it with everyone. Women of every age, race, economic group, lifestyle and sexuality are welcome. Women are invited to express themselves freely both verbally and visually to other women and the whole community.” When we first conceived of “Doin’ It in Public,” we wanted to incorporate the principles of feminist art education into our process. -

Woman's Building Records LSC.1982

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8dn45sp No online items Finding aid for the Woman's Building Records LSC.1982 Stacy Wood; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 9 March 2021. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding aid for the Woman's LSC.1982 1 Building Records LSC.1982 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Woman's Building records Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1982 Physical Description: 3 Linear Feet(5 boxes and 1 oversized flat box) Date (inclusive): 1975-1994 Abstract: The Woman's Building was a feminist community space that served as an educational facility and central icon in the feminist art and larger political movements. During its eighteen year lifespan, it housed conferences, performances, exhibitions and community events in downtown Los Angeles. This collection contains materials produced at the Woman's Building, exhibition catalogs, newsletters and calendars as well as information about different internal and external affiliated groups. COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements COLLECTION CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: Audiovisual materials in this collection will require assessment and possible digitization for safe access. -

Nancy Buchanan Nancybuchanan.Net Curriculum Vitae 1969 BA, University of California, Irvine 1971 MFA, University of California

Nancy Buchanan nancybuchanan.net Curriculum Vitae 1969 BA, University of California, Irvine 1971 MFA, University of California, Irvine EXHIBITIONS/VIDEO SCREENINGS/MEDIA PRESENTATIONS 2020 Artists + Poets, http://suturo.com/artistsandpoems/index.php Show Me the Signs, Blum + Poe, Los Angeles, CA Virtual Talks with Media Activists, https://mediaburn.org/events/virtual-talks-with-video-activists/nancy-buchanan/ Digital Power, https://digital-power.siggraph.org/ ACM SIGGRAPH Do Not Link, http://www.upstream.gallery 2019 California Winter, Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles, CA With a Little Help from My Friends — A Benefit for Bryan Chagolla, Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles These Creatures, Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art, Rancho Cucamunga, CA The Vision Board, Paul Kopeiken Gallery, Culver City, CA Book Launch — Hair Stories, POTTS, Alhambra, CA 2018 Functional – Small Ceramic Works, Future Studio Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Collecting on the Edge, Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, Logan, Utah Remote Castration, LAXART, Los Angeles, CA Group video screening, Provisional Gallery, San Francisco, CA Tow Truck Towing a Tow Truck, as-is.la, Los Angeles, CA 2017 Pursuing the Unpredictable: The New Museum 1977 – 2017, New York, NY Faces: Gender, Art, Technology: 20 years of interactions, connections and collaborations, Schaumbad, Graz, Austria MFRU 2017 Computer Art, various locations, Maribor, Slovenia Consumption, Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (solo show) Nancy Buchanan, Morgan Canavan, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, -

State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970

November 13, 2013 State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 Una DimitriJevic State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970 3 October 2013 – 12 January 2014 Smart Museum of Art, Chicago Review by Una DimitriJevic of Brave New Art World Organised as part of the landmark Pacific Standard Time initiative by the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAM/PFA), and the Orange County Museum of Art,’ State of Mind: New California Art Circa 1970’ is the first in-depth survey of conceptual art from California. Unlike their counterparts on the East coast, these Californian artists (whose collective output is represented here through more than 150 works by 60 artists and collectives) developed their ideas http://www.thisistomorrow.info/viewArticle.aspx?artId=2128 far from the highly monetised art-world and did not hesitate to confront questions about art-making and the role of artists with a good dose of humour. Their focus was on ideas and the artistic process, with the end-product itself seen as a secondary affair, a documentary relic. This was coupled with a desire to circumvent the traditional system of displaying and selling art. As such, much of the art produced by the California conceptualists consisted of happenings, public interventions and performances which are by their very nature ephemeral and irreproducible. All that can be represented in a gallery space is documentation of their occurrence: mainly video and photography, as well as the occasional scathing news article such as 'Conceptual Art – Just what is it?' from a 1971 edition of the Chronicle.