Genitourinary Pathogen Nucleic Acid Detection Panel Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmittal 3771, Claims Processing

Department of Health & CMS Manual System Human Services (DHHS) Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 3771 Date: May 12, 2017 Change Request 10055 SUBJECT: New Waived Tests I. SUMMARY OF CHANGES: This Change Request (CR) will inform contractors of new Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) waived tests approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Since these tests are marketed immediately after approval, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) must notify its contractors of the new tests so that the contractors can accurately process claims. There are 12 newly added waived complexity tests. The initial release of this Recurring Update Notification applies to Chapter 16, section 70.8 of the IOM. EFFECTIVE DATE: January 1, 2017 *Unless otherwise specified, the effective date is the date of service. IMPLEMENTATION DATE: July 3, 2017 Disclaimer for manual changes only: The revision date and transmittal number apply only to red italicized material. Any other material was previously published and remains unchanged. However, if this revision contains a table of contents, you will receive the new/revised information only, and not the entire table of contents. II. CHANGES IN MANUAL INSTRUCTIONS: (N/A if manual is not updated) R=REVISED, N=NEW, D=DELETED-Only One Per Row. R/N/D CHAPTER / SECTION / SUBSECTION / TITLE N/A N/A III. FUNDING: For Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs): The Medicare Administrative Contractor is hereby advised that this constitutes technical direction as defined in your contract. CMS does not construe this as a change to the MAC Statement of Work. -

List of SARS-Cov-2 Diagnostic Test Kits and Equipments Eligible For

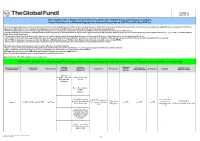

Version 33 2021-09-24 List of SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic test kits and equipments eligible for procurement according to Board Decision on Additional Support for Country Responses to COVID-19 (GF/B42/EDP11) The following emergency procedures established by WHO and the Regulatory Authorities of the Founding Members of the GHTF have been identified by the QA Team and will be used to determine eligibility for procurement of COVID-19 diagnostics. The product, to be considered as eligible for procurement with GF resources, shall be listed in one of the below mentioned lists: - WHO Prequalification decisions made as per the Emergency Use Listing (EUL) procedure opened to candidate in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) to detect SARS-CoV-2; - The United States Food and Drug Administration’s (USFDA) general recommendations and procedures applicable to the authorization of the emergency use of certain medical products under sections 564, 564A, and 564B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; - The decisions taken based on the Canada’s Minister of Health interim order (IO) to expedite the review of these medical devices, including test kits used to diagnose COVID-19; - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for inclusion on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on the basis of the Expedited TGA assessment - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare after March 2020 with prior scientific review by the PMDA - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests listed on the French -

Recommended Laboratory HIV Testing Algorithm for Serum Or Impact of HIV/AIDS

Journal of HIV for Clinical and Scientific Research eertechz Uğur Tüzüner*, Begüm Saran Gülcen Review article and Mehmet Özdemir Necmettin Erbakan University, Meram Medical Faculty, Medical Microbiology Department, Medical Virology Laboratory Algorithm in HIV Division. Konya, Turkey Dates: Received: 02 April, 2016; Accepted: 18 April, Infection Diagnosis 2016; Published: 19 April, 2016 *Corresponding author: Dr. Uğur Tüzüner, Abstract Necmettin Erbakan University, Meram Medical Faculty, Medical Microbiology Department, AIDS caused by HIV is an infection disease which was defined firstly in the USA in 1981. Since Konya, Turkey, Tel:+90 332 223 7029; E-mail: then, number of AIDS patients has increased continuously. About 36.9 million people are living with HIV around the world. Approximately 15 million people living with HIV were receiving antiretroviral therapy. Early detection is important due to the high risk of transmission that precedes seroconversion www.peertechz.com and also because it provides an opportunity to improve health outcomes with an early antiretroviral therapy. HIV testing is the key part of diagnosis and prevention efforts. Many tests have been used ISSN: 2455-3786 in the diagnosis of HIV over years and with developing testing methods, accuracy of the laboratory Keywords: HIV; Laboratory diagnosis; Algorithm diagnosis of HIV infection has been improved. Detecting p24 antigens, HIV 1-2 antibodies and HIV nucleic acid demonstrated that antibody testing alone might miss a considerable percentage of HIV infections detectable by these tests. This review provides updated recommendations and algorithm for HIV testing that are necessary for diagnosing HIV and offers approaches for accurate assessment of test results. Introduction HIV infection (asymptomatic HIV infection or clinical latency), and progression to AIDS (the late stage of HIV infection). -

Rapid Review: Performance and Feasibility of Rapid COVID-19 Tests

COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group Rapid Evidence Report Do the rapid COVID-19 tests on the market represent a feasible opportunity for Alberta? 1. What are the reported performance characteristics of the rapid COVID-19 tests that have been approved for commercial (diagnostic) use in Canada? 2. What are the optimal strategies for deployment of rapid testing, to improve either clinical care or outbreak control in health care and community settings? Context • It is unclear how the rapid (point-of-care) molecular and antigen tests for COVID-19 tests compare to each other. • Five point-of-care testing devices/systems have been approved for diagnostic use by Health Canada: 1) BD Veritor System for Rapid Detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Becton Dickinson and Company) 2) BKit Virus Finder COVID-19 (Hyris Ltd.) 3) ID NOW COVID-19 (Abbott Diagnostics Scarborough Inc.) 4) Panbio COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device (Abbott Rapid Diagnostics) 5) Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 (Cepheid). • The federal government has committed to distributing the consumables for the Abbott ID NOW and PanBio testing kits to each Canadian jurisdiction, however, the strategy for deploying the rapid test kits will be the responsibility of the public health leaders in the provincial/territorial governments. • The implementation of rapid testing in other jurisdictions offers an opportunity to learn from their experiences in deploying rapid COVID-19 tests and avoid potential missteps. These implementation activities have included mass assessments, population-level testing to determine prevalence, returned traveler assessment, staff screening at long-term care facilities, and school testing. Key Messages from the Evidence Summary • The body of evidence for rapid testing platforms is poor – many of the studies are at high risk of bias. -

Lower Respiratory SARS-Cov-2 Testing for Lung Donors

Notice of OPTN Emergency Policy Change Lower Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Testing for Lung Donors Sponsoring Committee: Ad Hoc Disease Transmission Advisory Policies Affected: Policy 1.2: Definitions Policy 2.9: Required Deceased Donor Infectious Disease Testing Public Comment: August 3, 2021-September 30, 2021 Board Approved: April 26, 2021 Effective Date: May 27, 2021 Summary of Changes The policy change defines what a lower respiratory specimen is and requires that all lung donors receive lower respiratory specimen testing by nucleic acid test (NAT). The policy specifies that testing results must be available pre-transplant of lungs. Purpose of Policy Change There has been accumulating evidence of a patient safety risk to lung recipients in four recent cases of deceased lung donors testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 by upper respiratory specimen and retrospectively testing positive by lower respiratory specimen. Three cases resulted in donor-derived transmission to lung recipients while the fourth resulted in lung discard. One lung recipient has died as a result of the donor-derived transmission. As of March 2021, only 60% of lung donors were tested by lower respiratory specimen.1 Policy is needed to ensure organ procurement organizations (OPOs) perform and obtain results from lower respiratory specimen testing for all potential deceased lung donors to avoid SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) transmission to lung recipients. The policy change is emergent because of the significant patient safety implications of donor-derived COVID-19 and the subsequent risk of patient mortality. The policy change requires nucleic acid testing (NAT) for COVID-19 by lower respiratory specimen for all potential deceased lung donors, with results being available prior to lung transplantation. -

Laboratory Testing for COVID-19

Laboratory Testing for COVID-19 Biotech Centre for Viral Disease Emergency National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Wenling Wang, PhD [email protected] October 19, 2020 Table of contents 2. Overview Testing 1. techniques PART ONE PART 01 Overview The identification of SARS-CoV-2 Jan 2, 2020 Jan 7, 2020 Samples arrived, RNA isolation and viral Visualization of SARS-CoV-2 with culture transmission electron microscopy 04 02 04 Jan 3, 2020 Jan 12, 2020 01 Whole genome sequencing 03 Sequences submitted to GISAID 03 Timeline of the key events of the COVID-19 outbreak Hu B., et al. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation dashboard Globally, as of 18 October 2020, there have been 39,596,858 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 1,107,374 deaths, reported to WHO. Symptoms of diseases caused by human coronavirus Headache Fever Overall soreness and ache Flu symptoms Chills Dry cough Vomiting PART TWO PART 02 Testing techniques Laboratory testing techniques for COVID-19 √ √ √ Nucleic acid Serological testing testing Viral isolation 2.1 Specimen collection requirements 2.2 Nucleic acid testing Contents 2.3 Antibody testing 2.4 Biosafety requirements Specimen collection Part I requirements ⚫ Collection target ⚫ Requirements for the sampling personnel ⚫ Specimen categories ⚫ Specimen processing ⚫ Specimen packaging and preservation ⚫ Specimen transportation 1. Specimen collection targets 1 Suspected COVID-19 cases; 2 Others requiring diagnosis or differential diagnosis for COVID-19 2. Sample collection requirements Sampling personnel 1. The COVID-2019 testing specimens shall be collected by qualified technicians who have passed biosafety training and are equipped with the corresponding laboratory skills. -

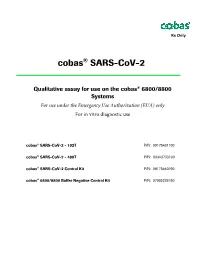

Cobas SARS-Cov-2 Instructions For

Rx Only ® cobas SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay for use on the cobas® 6800/8800 Systems For use under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) only For in vitro diagnostic use cobas® SARS-CoV-2 - 192T P/N: 09175431190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 - 480T P/N: 09343733190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Control Kit P/N: 09175440190 cobas® 6800/8800 Buffer Negative Control Kit P/N: 07002238190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Table of contents Intended use ............................................................................................................................ 5 Summary and explanation of the test ................................................................................. 5 Reagents and materials ......................................................................................................... 7 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 reagents and controls ............................................................................................. 7 cobas omni reagents for sample preparation .......................................................................................... 9 Reagent storage and handling requirements ......................................................................................... 10 Additional materials required ................................................................................................................. 11 Instrumentation and software required ................................................................................................. 12 Precautions and handling requirements ........................................................................ -

Biofire® Respiratory Panel 2.1 (RP2.1)

423738 ® BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1 (RP2.1) For Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) only Rx Only Instructions for Use https://www.biofiredx.com/e-labeling/ITI0101 Quick Guide https://www.biofiredx.com/e-labeling/ITI0072 Safety Data Sheet (SDS) https://www.biofiredx.com/e-labeling/ITI0060 Phone: 1-800-735-6544 (toll free) Customer and Technical Support Information U.S. Customers E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.biofiredx.com *For more information on how to contact Contact the local bioMérieux sales Customer and Technical Support, refer to Outside of the U.S. Appendix B. representative or an authorized distributor. INTENDED USE The BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1 (RP2.1) is a multiplexed nucleic acid test intended for the simultaneous qualitative detection and differentiation of nucleic acids from multiple viral and bacterial respiratory organisms, including nucleic acid from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), in nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) obtained from individuals suspected of COVID-19 by their healthcare provider. Testing is limited to laboratories certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a, that meet requirements to perform high complexity or moderate complexity tests. The BioFire Respiratory Panel 2.1 (RP2.1) is intended for the detection and differentiation of nucleic acid from SARS- CoV-2 and the following organism types and subtypes identified using the BioFire RP2.1. Viruses Bacteria Adenovirus Bordetella parapertussis Coronavirus 229E Bordetella -

Nucleic Acid-Based Diagnostic Tests for the Detection SARS-Cov-2: an Update

diagnostics Review Nucleic Acid-Based Diagnostic Tests for the Detection SARS-CoV-2: An Update Choo Yee Yu 1 , Kok Gan Chan 2 , Chan Yean Yean 3,* and Geik Yong Ang 4,* 1 Independent Researcher, Kuala Lumpur 51200, Malaysia; [email protected] 2 Division of Genetics and Molecular Biology, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kota Bharu 16150, Malaysia 4 Faculty of Sports Science and Recreation, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam 40450, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.Y.Y.); [email protected] (G.Y.A.) Abstract: The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) began as a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China before spreading to over 200 countries and territories on six continents in less than six months. Despite rigorous global containment and quarantine efforts to limit the transmission of the virus, COVID-19 cases and deaths have continued to increase, leaving devastating impacts on the lives of many with far- reaching effects on the global society, economy and healthcare system. With over 43 million cases and 1.1 million deaths recorded worldwide, accurate and rapid diagnosis continues to be a cornerstone of pandemic control. In this review, we aim to present an objective overview of the latest nucleic acid-based diagnostic tests for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 that have been authorized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under emergency use authorization (EUA) as of 31 October 2020. -

The Point-Of-Care Diagnostic Landscape for Sexually Transmitted Infections (Stis)

The Point-of-Care Diagnostic Landscape for Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) Maurine M. Murtagh The Murtagh Group, LLC 2019 1 Introduction Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a significant global public health issue, with an estimated 378 million people becoming ill in 2016 with one of 4 STIs: syphilis, Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG), and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) (1) . In addition, more than 291 million women have a human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, which is a necessary cause of high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (grade 2 or higher [CIN2+]) (1). This report considers the available and pipeline diagnostics for curable STIs, namely syphilis, CT, NG, TV, and HPV. With some exceptions, the existing diagnostics for these STIs are laboratory-based platforms, which typically require strong infrastructure and well-trained laboratory technicians. In addition, test turnaround time (TAT) is often long, requiring patients to return for test results on a subsequent clinic visit. This, in turn, leads to significant loss to follow-up. Therefore, while these laboratory-based diagnostics are effective, they may not always be suitable for use in resource-limited settings where diagnostic access and delivery are difficult. There are now a variety of tests available for use at or near the point of patient care (POC) for STIs (2). These include a wide range of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and syphilis, among others, with which it is possible to detect infection using fingerprick blood, or in some cases, oral fluid.1 In addition, other types of POC tests, including simple molecular tests for use in primary healthcare settings, have also become available recently. -

Principles Behind the Technology for Detecting SARS-Cov-2, the Cause of COVID-19

Editors’ Note: The co-editors of the Hawaiʻi Journal of Health & Social Welfare extend our warmest wishes to our readers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our health care brethren around the world and here in Hawaiʻi are bringing their collective expertise to help quell the pandemic and minimize the loss of human life. In this issue, we are pleased to offer three non-peer reviewed guest columns to help our readers understand some of the key issues of COVID-19. Stay safe and be well. — S. Kalani Brady and Tonya Lowery St. John COVID-19 Special Column: Principles Behind the Technology for Detecting SARS-CoV-2, the Cause of COVID-19 Lauren Ching BS; Sandra P. Chang PhD; and Vivek R. Nerurkar PhD Abstract LFIA = lateral flow immunoassay M = membrane protein Nationwide shortages of tests that detect severe acute respiratory syndrome MERS-CoV = Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and diagnose coronavirus disease 2019 (CO- MIA = microsphere immunoassay VID-19) have led the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to significantly N = nucleocapsid protein relax regulations regarding COVID-19 diagnostic testing. To date the FDA has NAT = nucleic acid test given emergency use authorization (EUA) to 48 COVID-19 in vitro diagnostic NAAT = nucleic acid amplification test tests and 21 high complexity molecular-based laboratory developed tests, as nsp = non-structural protein well as implemented policies that give broad authority to clinical laboratories ORF = open reading frame and commercial manufacturers in the development, distribution, and use of POC = point-of-care COVID-19 diagnostic tests. Currently, there are 2 types of diagnostic tests qRT-PCR = real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction available for the detection of SARS-CoV-2: (1) molecular and (2) serological RNA = ribonucleic acid tests. -

Recommended Laboratory HIV Testing Algorithm for Serum Or Plasma Specimens

Recommended Laboratory HIV Testing Algorithm for Serum or Plasma Specimens 1. Laboratories should conduct initial testing for HIV with an FDA-approved antigen/antibody combination immunoassay* that detects HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies and HIV-1 p24 antigen to test for established HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection and for acute HIV-1 infection. No further testing is required for specimens that are nonreactive on the initial immunoassay. 2. Specimens with a reactive antigen/antibody combination immunoassay result (or repeatedly reactive, if repeat testing is recommended by the manufacturer or required by regulatory authorities) should be tested with an FDA-approved antibody immunoassay that differentiates HIV-1 antibodies from HIV-2 antibodies. Reactive results on the initial antigen/antibody combination immunoassay and the HIV- 1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay should be interpreted as positive for HIV-1 antibodies, HIV-2 antibodies, or HIV antibodies, undifferentiated. 3. Specimens that are reactive on the initial antigen/antibody combination immunoassay and nonreactive or indeterminate on the HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay should be tested with an FDA-approved HIV-1 nucleic acid test (NAT). A reactive HIV-1 NAT result and nonreactive HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay result indicates laboratory evidence for acute HIV-1 infection. A reactive HIV-1 NAT result and indeterminate HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay result indicates the presence of HIV-1 infection confirmed by HIV-1 NAT. A negative HIV-1 NAT result and nonreactive or indeterminate HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay result indicates a false-positive result on the initial immunoassay.