Rapid Review: Performance and Feasibility of Rapid COVID-19 Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmittal 3771, Claims Processing

Department of Health & CMS Manual System Human Services (DHHS) Pub 100-04 Medicare Claims Processing Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Transmittal 3771 Date: May 12, 2017 Change Request 10055 SUBJECT: New Waived Tests I. SUMMARY OF CHANGES: This Change Request (CR) will inform contractors of new Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) waived tests approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Since these tests are marketed immediately after approval, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) must notify its contractors of the new tests so that the contractors can accurately process claims. There are 12 newly added waived complexity tests. The initial release of this Recurring Update Notification applies to Chapter 16, section 70.8 of the IOM. EFFECTIVE DATE: January 1, 2017 *Unless otherwise specified, the effective date is the date of service. IMPLEMENTATION DATE: July 3, 2017 Disclaimer for manual changes only: The revision date and transmittal number apply only to red italicized material. Any other material was previously published and remains unchanged. However, if this revision contains a table of contents, you will receive the new/revised information only, and not the entire table of contents. II. CHANGES IN MANUAL INSTRUCTIONS: (N/A if manual is not updated) R=REVISED, N=NEW, D=DELETED-Only One Per Row. R/N/D CHAPTER / SECTION / SUBSECTION / TITLE N/A N/A III. FUNDING: For Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs): The Medicare Administrative Contractor is hereby advised that this constitutes technical direction as defined in your contract. CMS does not construe this as a change to the MAC Statement of Work. -

List of SARS-Cov-2 Diagnostic Test Kits and Equipments Eligible For

Version 33 2021-09-24 List of SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic test kits and equipments eligible for procurement according to Board Decision on Additional Support for Country Responses to COVID-19 (GF/B42/EDP11) The following emergency procedures established by WHO and the Regulatory Authorities of the Founding Members of the GHTF have been identified by the QA Team and will be used to determine eligibility for procurement of COVID-19 diagnostics. The product, to be considered as eligible for procurement with GF resources, shall be listed in one of the below mentioned lists: - WHO Prequalification decisions made as per the Emergency Use Listing (EUL) procedure opened to candidate in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) to detect SARS-CoV-2; - The United States Food and Drug Administration’s (USFDA) general recommendations and procedures applicable to the authorization of the emergency use of certain medical products under sections 564, 564A, and 564B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; - The decisions taken based on the Canada’s Minister of Health interim order (IO) to expedite the review of these medical devices, including test kits used to diagnose COVID-19; - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for inclusion on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on the basis of the Expedited TGA assessment - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare after March 2020 with prior scientific review by the PMDA - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests listed on the French -

Rapid Antigen Detection Test for Group a Streptococcus in Children with Pharyngitis (Review)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis (Review) Cohen JF, Bertille N, Cohen R, Chalumeau M Cohen JF, Bertille N, Cohen R, Chalumeau M. Rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 7. Art. No.: CD010502. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010502.pub2. www.cochranelibrary.com Rapid antigen detection test for group A streptococcus in children with pharyngitis (Review) Copyright © 2016 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 3 BACKGROUND .................................... 5 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 7 METHODS ...................................... 7 RESULTS....................................... 10 Figure1. ..................................... 11 Figure2. ..................................... 12 Figure3. ..................................... 13 Figure4. ..................................... 15 Figure5. ..................................... 16 Figure6. ..................................... 18 Figure7. ..................................... 20 DISCUSSION ..................................... 21 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 23 REFERENCES ..................................... 24 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 42 DATA ....................................... -

Recommended Laboratory HIV Testing Algorithm for Serum Or Impact of HIV/AIDS

Journal of HIV for Clinical and Scientific Research eertechz Uğur Tüzüner*, Begüm Saran Gülcen Review article and Mehmet Özdemir Necmettin Erbakan University, Meram Medical Faculty, Medical Microbiology Department, Medical Virology Laboratory Algorithm in HIV Division. Konya, Turkey Dates: Received: 02 April, 2016; Accepted: 18 April, Infection Diagnosis 2016; Published: 19 April, 2016 *Corresponding author: Dr. Uğur Tüzüner, Abstract Necmettin Erbakan University, Meram Medical Faculty, Medical Microbiology Department, AIDS caused by HIV is an infection disease which was defined firstly in the USA in 1981. Since Konya, Turkey, Tel:+90 332 223 7029; E-mail: then, number of AIDS patients has increased continuously. About 36.9 million people are living with HIV around the world. Approximately 15 million people living with HIV were receiving antiretroviral therapy. Early detection is important due to the high risk of transmission that precedes seroconversion www.peertechz.com and also because it provides an opportunity to improve health outcomes with an early antiretroviral therapy. HIV testing is the key part of diagnosis and prevention efforts. Many tests have been used ISSN: 2455-3786 in the diagnosis of HIV over years and with developing testing methods, accuracy of the laboratory Keywords: HIV; Laboratory diagnosis; Algorithm diagnosis of HIV infection has been improved. Detecting p24 antigens, HIV 1-2 antibodies and HIV nucleic acid demonstrated that antibody testing alone might miss a considerable percentage of HIV infections detectable by these tests. This review provides updated recommendations and algorithm for HIV testing that are necessary for diagnosing HIV and offers approaches for accurate assessment of test results. Introduction HIV infection (asymptomatic HIV infection or clinical latency), and progression to AIDS (the late stage of HIV infection). -

Options for the Use of Rapid Antigen Tests for COVID-19 JD

TECHNICAL REPORT Options for the use of rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 in the EU/EEA and the UK 19 November 2020 Key messages Rapid antigen tests can contribute to overall COVID-19 testing capacity, offering advantages in terms of shorter turnaround times and reduced costs, especially in situations in which RT-PCR testing capacity is limited. Test sensitivity for rapid antigen tests is generally lower than for RT-PCR. Rapid antigen tests perform best in cases with high viral load, in pre-symptomatic and early symptomatic cases up to five days from symptom onset. ECDC agrees with the minimum performance requirements set by WHO at ≥80% sensitivity and ≥97% specificity. ECDC recommends that EU Member States perform independent and setting-specific validations of rapid antigen tests before their implementation. The use of rapid antigen tests is appropriate in high prevalence settings when a positive result is likely to indicate true infection, as well as in low prevalence settings to rapidly identify highly infectious cases. Rapid antigen tests can help reduce further transmission through early detection of highly infectious cases, enabling a rapid start of contact tracing. Scope of this document On 28 October 2020, a European Commission Recommendation on COVID-19 testing strategies, including the use of rapid antigen tests was published [1]. That recommendation calls for European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) Member States and the United Kingdom (UK) to agree on criteria to be used for the selection of rapid antigen tests, and to share and discuss information regarding the results of validation studies. This ECDC document is intended to facilitate further discussions between Member States with the aim of reaching agreement on the criteria to be used for the selection of rapid antigen tests, as well as scenarios and settings during which it is appropriate to use rapid antigen tests. -

Diagnostic COVID-19 Testing Faqs

Diagnostic COVID-19 Testing FAQs Q: What testing is currently available to diagnose active COVID-19 infection? A: There are two types of COVID-19 tests available – a traditional PCR test that is sent to a lab and a Rapid Antigen Test that is run on site. Each test is performed by taking a swab from the nose to test for the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 (the virus causing COVID-19). Q: How long does it take to get results and how accurate are they? A: PCR Test: It takes approximately 3-5 days for a result to be returned from our lab and has a high degree of accuracy both for positives and negatives. Rapid Antigen Test: The advantage of this test is the ability to get a result while you wait, usually within 15 minutes. This test has a high accuracy rate for positive test results, but approximately an 85% accuracy rate for negative results. Q: What does a positive test result mean? A: A positive test for COVID-19 indicates active infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Q: What does a negative test result mean? A: A negative test for COVID-19 means an individual was probably not infected at the time their sample was collected. However, that does not mean they will not get sick in the future. False negatives can also be possible, particularly with antigen testing. Q: If I choose a Rapid Antigen Test and my result is negative, what should I do? A: If you are suffering from symptoms or have been exposed to someone with COVID-19, you will need to have a PCR test to verify your negative test result. -

Idaho Interim Guidance on Use of Rapid Antigen Tests for COVID-19

Idaho Interim Guidance on Use of Rapid Antigen Tests for COVID-19 Revised March 2021 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for several rapid antigen tests, which greatly increase point-of-care testing options for COVID-19. Rapid antigen tests are less complex than most molecular tests and provide results in 30 minutes or less. As point of care diagnostics, they can be used in doctors’ offices and other facilities with a valid Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) Certificate of Waiver. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, the gold-standard for COVID-19 diagnosis, is both highly sensitive and specific but requires more complex laboratory expertise and equipment and is not available as a point of care test. Rapid antigen tests are less sensitive than the RT-PCR test, which means that more viral particles must be present in the nose (or other approved sampling site) to generate the positive result. Lower sensitivity means that false negatives may occur more frequently, particularly very early or very late in the course of infection. All authorized rapid antigen tests have specificity similar to RT-PCR, which means that false positive results are expected to occur about as frequently as with an RT-PCR test. False positive results can occur and are most likely to occur in populations where the prevalence of SARS-CoV- 2 infection is low. People with COVID-19 disease tend to shed greater amounts of virus within the first five days of symptom onset. After viral shedding peaks, it steadily declines over 10 to 20 days depending on the patient’s immune response and the severity of disease. -

Lower Respiratory SARS-Cov-2 Testing for Lung Donors

Notice of OPTN Emergency Policy Change Lower Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Testing for Lung Donors Sponsoring Committee: Ad Hoc Disease Transmission Advisory Policies Affected: Policy 1.2: Definitions Policy 2.9: Required Deceased Donor Infectious Disease Testing Public Comment: August 3, 2021-September 30, 2021 Board Approved: April 26, 2021 Effective Date: May 27, 2021 Summary of Changes The policy change defines what a lower respiratory specimen is and requires that all lung donors receive lower respiratory specimen testing by nucleic acid test (NAT). The policy specifies that testing results must be available pre-transplant of lungs. Purpose of Policy Change There has been accumulating evidence of a patient safety risk to lung recipients in four recent cases of deceased lung donors testing negative for SARS-CoV-2 by upper respiratory specimen and retrospectively testing positive by lower respiratory specimen. Three cases resulted in donor-derived transmission to lung recipients while the fourth resulted in lung discard. One lung recipient has died as a result of the donor-derived transmission. As of March 2021, only 60% of lung donors were tested by lower respiratory specimen.1 Policy is needed to ensure organ procurement organizations (OPOs) perform and obtain results from lower respiratory specimen testing for all potential deceased lung donors to avoid SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) transmission to lung recipients. The policy change is emergent because of the significant patient safety implications of donor-derived COVID-19 and the subsequent risk of patient mortality. The policy change requires nucleic acid testing (NAT) for COVID-19 by lower respiratory specimen for all potential deceased lung donors, with results being available prior to lung transplantation. -

Performance Evaluation of Three Rapid Antigen Tests for the Diagnosis of Group a Streptococci

Open access Research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025438 on 5 August 2019. Downloaded from Performance evaluation of three rapid antigen tests for the diagnosis of group A Streptococci Ha-Nui Kim, Jeeyong Kim, Woong Sik Jang, Jeonghun Nam, Chae Seung Lim To cite: Kim H-N, Kim J, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Jang WS, et al. Performance Objective To compare the diagnostic performance of evaluation of three rapid antigen three rapid antigen detection tests (RADTs) for group A tests for the diagnosis of group ► This study compared the diagnostic performance of Streptococcus (GAS). A Streptococci. BMJ Open three rapid antigen detection tests (RADTs) with two Design A hospital-based, cross-sectional, retrospective 2019;9:e025438. doi:10.1136/ references, the group A Streptococcus streptococcal study. bmjopen-2018-025438 pyrogenic exotoxin B (speB) gene PCR and culture Setting A comparative study of rapid diagnostic tests for methods. ► Prepublication history for GAS using clinical specimens in a single institute. ► The careUS Strep A Plus is a useful test that is highly this paper is available online. Participants 225 children in the outpatient clinics ofKorea comparable with the ‘reference standard’ test. To view these files please visit University Guro Hospitalwith suspicious symptoms were the journal online (http:// dx. doi. ► We used samples stored below −70°C in a 10 mL subjected to throat swab sampling. A dual-swab applicator org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018- transport tube containing 1 mL liquid Stuart’s trans- was used. Samples were stored at below −70°C in a 025438). -

COVID-19 TESTING Frequently Asked Questions

COVID-19 TESTING Frequently Asked Questions Who is eligible for COVID-19 testing at UR Medicine Urgent Care? Testing is now available for everyone – whether ill with COVID-19 symptoms or asymptomatic. For testing requested based on rapid positive results, exposure or symptoms, you may require further testing and additional costs may be incurred. What is a COVID-19 Rapid Antigen Test, and how does it differ from a PCR test? The antigen test, or rapid test, detects if a patient is currently infected with COVID-19. The PCR test is considered the “gold standard” in COVID-19 detection. This test confirms with higher accuracy if a patient currently has the virus.* Which type of test will I get? For patients without COVID-19 symptoms and not exposed to a COVID-19 positive individual, a rapid test will be administered. For individuals with COVID-19 symptoms, or have been exposed to a confirmed COVID-19 positive individual, a PCR test will be administered. How long does it take to get results from a COVID-19 test? The rapid test offers results in about 15 minutes during your visit. Typically, individuals receive PCR test results within 24 to 48 hours. However, this can be delayed due to high demand. How do I find out the results of the PCR test? The quickest way to find out your PCR test results is to sign up for MyChart atmychart.urmc.edu How much does a rapid test cost? Since the rapid test is not covered by insurance for asymptomatic, non-exposed patients, it is a self-pay service. -

Laboratory Testing for COVID-19

Laboratory Testing for COVID-19 Biotech Centre for Viral Disease Emergency National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Wenling Wang, PhD [email protected] October 19, 2020 Table of contents 2. Overview Testing 1. techniques PART ONE PART 01 Overview The identification of SARS-CoV-2 Jan 2, 2020 Jan 7, 2020 Samples arrived, RNA isolation and viral Visualization of SARS-CoV-2 with culture transmission electron microscopy 04 02 04 Jan 3, 2020 Jan 12, 2020 01 Whole genome sequencing 03 Sequences submitted to GISAID 03 Timeline of the key events of the COVID-19 outbreak Hu B., et al. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation dashboard Globally, as of 18 October 2020, there have been 39,596,858 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 1,107,374 deaths, reported to WHO. Symptoms of diseases caused by human coronavirus Headache Fever Overall soreness and ache Flu symptoms Chills Dry cough Vomiting PART TWO PART 02 Testing techniques Laboratory testing techniques for COVID-19 √ √ √ Nucleic acid Serological testing testing Viral isolation 2.1 Specimen collection requirements 2.2 Nucleic acid testing Contents 2.3 Antibody testing 2.4 Biosafety requirements Specimen collection Part I requirements ⚫ Collection target ⚫ Requirements for the sampling personnel ⚫ Specimen categories ⚫ Specimen processing ⚫ Specimen packaging and preservation ⚫ Specimen transportation 1. Specimen collection targets 1 Suspected COVID-19 cases; 2 Others requiring diagnosis or differential diagnosis for COVID-19 2. Sample collection requirements Sampling personnel 1. The COVID-2019 testing specimens shall be collected by qualified technicians who have passed biosafety training and are equipped with the corresponding laboratory skills. -

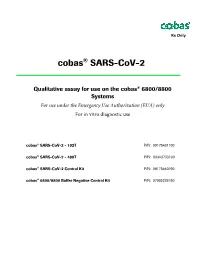

Cobas SARS-Cov-2 Instructions For

Rx Only ® cobas SARS-CoV-2 Qualitative assay for use on the cobas® 6800/8800 Systems For use under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) only For in vitro diagnostic use cobas® SARS-CoV-2 - 192T P/N: 09175431190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 - 480T P/N: 09343733190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Control Kit P/N: 09175440190 cobas® 6800/8800 Buffer Negative Control Kit P/N: 07002238190 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Table of contents Intended use ............................................................................................................................ 5 Summary and explanation of the test ................................................................................. 5 Reagents and materials ......................................................................................................... 7 cobas® SARS-CoV-2 reagents and controls ............................................................................................. 7 cobas omni reagents for sample preparation .......................................................................................... 9 Reagent storage and handling requirements ......................................................................................... 10 Additional materials required ................................................................................................................. 11 Instrumentation and software required ................................................................................................. 12 Precautions and handling requirements ........................................................................