Architectural / Stylistic / Material Aspects of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Views and Opinions Expressed in This Document Are Those of the Author and Do Not Necessarily

Department of Environmental Studies DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PAGE The undersigned have examined the dissertation entitled: Ramapough/Ford: The Impact and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy presented by Chuck Stead candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that it is accepted. Committee Chair Name: Alesia Maltz Title/Affiliation: Antioch University Committee Member Name: Charlene DeFreese Title/Affiliation: Ramapough Lenape Nation Committee Member Name: Michael Edelstein Title/Affiliation: Ramapo College of New Jersey Committee Member Name: Tania Schusler Title/Affiliation: Antioch University Defense Date: August 22, 2014 Ramapough/Ford: The Impact and Survival of an Indigenous Community in the Shadow of Ford Motor Company’s Toxic Legacy By: Chuck Stead A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Environmental Studies at Antioch University New England Committee: Alesia Maltz, Ph.D. (Chair) Tania Schusler, Ph.D. Michael Edelstein, Ph.D. Sub-Chief Charlene DeFreese 2015 The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the reviewers or Antioch University. i This is dedicated to the elders. ii Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Antioch School of Environmental Studies, and the Doctorial Committee, Dr. Michael Edelstein, Dr. Tania Shuster, Charlene Defreese and Dr. Alesia Maltz for their guidance, as well as my cohort colleague Claudia Ford. I would also like to thank the members of the Ramapo Lenape Nation especially Chief Perry, Chief Mann, and Vivian Milligan for their support and guidance. -

The Vernacular Houses of Harlan County, Kentucky

-ABSTRACT WHAT is the vernacular ? Are some houses vernacular while others are not? Traditional definitions suggest that only those buildings that are indigenous, static and handmade can be considered vernacular. This thesis uses Harlan County, Kentucky as a case study to argue that vernacular architecture includes not only those houses that are handmade, timeless and traditional but also those houses that are industrial and mass-produced. Throughout the 19 th century Harlan County was an isolated, mountainous region where settlers built one and two-room houses from logs, a readily available material. At the turn of the century a massive coal boom began, flooding the county with people and company-built coal camp houses which were built in large quantities as cheaply as possible with milled lumber and hired help. Given traditional conceptions of the vernacular, it would have been appropriate to assume the vernacular tradition of house building ended as camp houses, those houses that were not built directly by the residents with manufactured materials, began to replace the traditional log houses. However, the research presented in this thesis concludes that many elements of form, construction and usage that were first manifest in the handmade log cabins continued to be expressed in the county’s mass-produced camp houses. These camp houses not only manifest an evolution of local building traditions but also established qualities of outside influence which in turn were embraced by the local culture. Harlan County’s houses make the case for a more inclusive conception of vernacular architecture. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 6 I. -

The Ordinary Iconic Ranch House Is About the Mid-20 -Century Ranch

1 The Ordinary Iconic Ranch House Mid-20th Century Ranch Houses in Georgia PART III: THE RANCH HOUSE IN AMERICA AFTER WORLD WAR II September 2011 Richard Cloues, Ph.D. The Ordinary Iconic Ranch House is about the mid-20th-century Ranch House in Georgia. It is presented in six parts. Part III (this part) documents the emergence of the Ranch House nationally as the favored house type at the middle of the 20th century. Other parts of The Ordinary Iconic Ranch House tell other parts of the Ranch House story. 2 World War II may have put the brakes on the housing industry, but not on people’s dreams of new houses. 3 A housing report issued just as the war was ending advised prospective homebuyers that “a California-styled house … like the ranch type … is your best bet for the post-war.” 4 And, as if to make the point, in 1946 a demonstration “Post-War House” was built in Los Angeles: A fabulous, ahead-of-its-time, Contemporary-style Ranch House … 5 sponsored by a consortium of architects, landscape architects, appliance manufacturers, and builders led by Ranch House architect Fritz Burns. 6 The house was widely publicized in popular magazines and newspapers. 7 Also in 1946, a national housing survey found that the typical American homeowner-to-be did in fact favor what was described as “the low, rambling … Ranch House which has come out of the Southwest.” 8 This book, edited by California Ranch-House designer Cliff May and published by Sunset Magazine in 1946, perhaps best illustrates what was “coming out of the Southwest” at that time: 9 long, low, linear Ranch Houses … 10 linear Ranch Houses with “clusters” of bedrooms at one end, an integral garage or carport at the other, and open family living spaces in between … 11 L-shaped or half-courtyard houses (in actuality, the linear Ranch House bent in the middle) … 12 full courtyard houses … 13 and the sprawling “rambling” Ranch House. -

Residential Pattern Book

Residential Pattern Book and Resource Manual PREmier Homes and Neighborhoods Preserve Renew Enhance City of Virginia Beach Department of Housing and Neighborhood Preservation 2424 Courthouse Drive, Building 18-A Virginia Beach, VA 23456 (757) 385-5750 http://www.vbgov.com/government/departments/housing-neighborhood- preservation/homeowners/Pages/Pattern-Book.aspx Revised 09.24.12 City of Virginia Beach Pattern Book Pattern Book Page | 2 City of Virginia Beach Pattern Book City Staff ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Natasha Wise, Administrative Technician Natalie Pierce, Special Projects Coordinator We hereby acknowledge the following people for their contributions to this Pattern Book: Olin Walden, Housing Development Coordinator Pattern Book Project Manager/ Principal Author Sharon Prescott, Housing Development Administrator th th 4 and 5 Year Design Students, Department of Architecture Andrew Friedman, Director Hampton University Department of Housing and Neighborhood Preservation Robert S. Herbert, Deputy City Manager Adreon Bell, Kirsten Bias, Spencer Ferguson, Carl Hamilton Walter Harris IV, Charelle Johnson, Leon Peters, Daniel Robinson, Carmen Ross, Joi Ruffin, Briana Smith, Marcus Thomas and Valecia Wilson Under the direction of Olin Walden, B. Arch, NOMA, Project Manager And to the citizens of Virginia Beach whose homes are shown throughout this document. Pattern Book Page | 3 City of Virginia Beach Pattern Book TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Welcome Home 6 Chapter 3: Home Styles 16 Welcome to the City of Virginia Beach Pattern Book 7 Common Housing -

VOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 7 | 1 APRIL 2020 REVIEWS the Earth Issue

Featuring 331 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 7 | 1 APRIL 2020 REVIEWS The Earth Issue Conversations with Hope Jahren, Michael Christie, Anuradha Rao, and more from the editor’s desk: Chairman Writing To Save the Planet HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy John Paraskevas courtesy Photo Few world figures in recent years have been as inspiring as Greta Thun- Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER berg, the 16-year-old Swedish activist who is the face of today’s environmental [email protected] Vice President of Marketing movement. Her example led tens of thousands of students across Europe to SARAH KALINA skip school on Fridays to protest government inaction on climate change and [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor still more young people and adults to march in the streets of the world’s cit- ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] ies. She has addressed the United Nations. She was nominated for the Nobel Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK Peace Prize. In December, she was named Time magazine’s Person of the Year. [email protected] Children’s Editor Sixteen of Thunberg’s remarkable speeches were recently collected in No VICKY SMITH [email protected] One Is Too Small To Make a Difference (2019). In a starred review, Kirkus called Young Adult Editor Tom Beer it “a tiny book, not much bigger than a pamphlet, with huge potential impact.” LAURA SIMEON [email protected] It’s just one of the dozens of outstanding titles about climate change and the environment that cross Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE our desks here at Kirkus. -

INTEGRATION of HISTORIC PRESERVATION and SUSTAINABILITY PRINCIPLES for LOCAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSIONS by KIMBERLY L. KO

INTEGRATION OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND SUSTAINABILITY PRINCIPLES FOR LOCAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSIONS by KIMBERLY L. KOOLES (Under the Direction of John Waters) ABSTRACT This thesis will serve to aide historic preservation commissions through the process of integrating sustainability into local historic preservation practices. Included will be models of energy efficiency updates, green modifications, and reasons for conserving the built and natural environment. INDEX WORDS: Historic Preservation, Historic Preservation Commissions, Design Guidelines, Sustainability, Solar Panels, Wind Turbines, Embodied Energy, Historic Districts INTEGRATION OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND SUSTAINABILITY PRINCIPLES FOR LOCAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSIONS by KIMBERLY L. KOOLES BA, College of Charleston, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Kimberly L. Kooles All Rights Reserved INTEGRATION OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND SUSTAINABILITY PRINCIPLES FOR LOCAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSIONS by KIMBERLY L. KOOLES Major Professor: John Waters Committee: James Reap Alfred Vick Jennifer Martin Lewis Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2009 DEDICATION To the greatest blessing life has given me personally, my parents. Thank You. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give my sincere thanks to everyone who has assisted in the completion of my thesis. My family has been unconditionally supportive throughout my time in graduate school, even more so down the winding road it took for me to recommence my studies. My exceptional friends who helped me through my sleepless nights and relentless fretting, thanks for reminding me that it is very important to take breaks from one’s computer for life’s greater moments. -

How Identity Influenced the Historic Forms of the William Brinton 1704 House Anthony Richard Carlos Hita University of Pennsylvania

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2018 One Building, Four Houses: How Identity Influenced the Historic Forms of the William Brinton 1704 House Anthony Richard Carlos Hita University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Hita, Anthony Richard Carlos, "One Building, Four Houses: How Identity Influenced the Historic Forms of the William Brinton 1704 House" (2018). Theses (Historic Preservation). 647. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/647 Suggested Citation: Hita, Anthony Carlos Hita (2018). One Building, Four Houses: How Identity Influenced the Historic Forms of the William Brinton 1704 House (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/647 For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Building, Four Houses: How Identity Influenced the Historic Forms of the William Brinton 1704 House Abstract Built in 1704 by early Chester County Quaker, William Brinton the Younger (1670-1751), the 1704 House underwent four substantial phases of use and modification--a genteel great house (1704-1752), an ornamental farmhouse (1829-1863), a moral rural homestead (1864-1953), and a Colonial Revival house museum (1954-2018). Each of these phases represented a different owner of the structure who modified it to meet their needs and priorities. This thesis examines who these individuals were, how they were influenced by their own conscious values and subconscious social norms, and why and how they adapted the 1704 House as a result. Today, following a 1954 restoration to its circa 1752 form, the house is interpreted mainly as a family shrine to the early Brintons, with little mention of the two intermediate phases. -

The Transition of Domestic Mormon Architecture in Cache Valley, Utah, 1860--1915

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2009 From Cultural Traditions to National Trends: The Transition of Domestic Mormon Architecture in Cache Valley, Utah, 1860--1915 Jami J. Van Huss Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Van Huss, Jami J., "From Cultural Traditions to National Trends: The Transition of Domestic Mormon Architecture in Cache Valley, Utah, 1860--1915" (2009). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 371. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/371 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, School of 5-1-2009 From Cultural Traditions to National Trends: The Transition of Domestic Mormon Architecture in Cache Valley, Utah, 1860--1915 Jami J. Van Huss Utah State University Recommended Citation Van Huss, Jami J., "From Cultural Traditions to National Trends: The Transition of Domestic Mormon Architecture in Cache Valley, Utah, 1860--1915" (2009). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. Paper 371. http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/371 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, School of at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. -

Mar Vista Community Council Community Plan Committee

Mar Vista Community Council Community Plan Committee INITIAL INPUT DOCUMENT MARCH 12, 2019 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Part A: General Considerations 6 I. Zoning .............................................................................6 Background 6 II. Mobility ..........................................................................15 Traffic 15 Emergency Evacuation 16 III. Infrastructure .................................................................16 Streets, the Urban Canopy and Urban Runoff 16 a. Streets 16 b. Urban Canopy 17 c. Urban Runoff 19 Summary ............................................................................21 Part B: Zone-Specific Input 22 Zone 1 .................................................................................22 Background 22 Goals 23 Zone 2 .................................................................................27 Zone 3 .................................................................................28 Zone 4 .................................................................................29 Housing 29 Transit Considerations 29 reCode LA 31 MVCC - Master Input Document $2 of $61 MAR VISTA - Boyer’s Grove 34 Biona Hills (Boyer’s Grove) 36 A Hidden Jewel 36! ZIMAS Map of Parcels Affected 37 Assessor Parcel Numbers for 11314 - 11325 38! Assessor Parcel Numbers for 11328 - 11335 39! Assessor Parcel Numbers for 11338 - 11345 40! Assessor Parcel Numbers for 11348 - 11361 41! Assessor Parcel Numbers for 11404 - 11421 42! Assessor Parcel Numbers for 11424 - 11435 43! reCode LA - Preserve -

Village of East Hampton Is an Incorporated Village of 2,000 Residents, Located Approximately 100 Miles East of New York City on Long Island's South Shore

NFS Form 10-800 0-82) OHB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received. ^ uunJUN T 1988 inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name ________________ historic_______________________________ ___________ and or common Villa8e of Eas t Hampton Multiple Resource Area 2. Location street & number various not for publication city, town East Hampton vicinity of state New York code 036 county Suffolk code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use x district(s) public x occupied agriculture .X _ museum building(s) private unoccupied — _ commercial x park structure x both work in progress educational x private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment x religious object in process yes: restricted x government scientific being considered x~ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation NA no military other: 4. Owner of Property name various street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Suffolk County Clerk's Office street & number Suffolk County Center city, town Riverhead state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys New York Statewide Inventory title °f Historic Resources has this property been determined eligible? yes no x date 1979 federal state county local Division for Historic Preservation depository for survey records city, town Albany state New York 7. Description Condition * Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered original site good ruins altered moved date fair . unexposed *Refer to district building lists for property specific data. -

Green House Manual North America

GREEN HOUSE MANUAL NORTH AMERICA A Bioclimatic Design Analysis Tulane University School of Architecture A publication of the Tulane City Center 1 GREEN HOUSE MANUAL A Bioclimatic Design Analysis Tulane School of Architecture In assembling this manual I was influenced by Rural and Urban House Types, PAMPLET ARCHITECTURE NO.9. That book presented a series of house types based on the needs and habits of its occupants. It documented not only the plan and design intent but also the form it implied; that logic belonging to a regional (site and climate) and an architectural (tradition) idea was expressed in the form. In teaching an environmental technology course at Tulane University; specifically the class on bioclimatic design, I have discussed these same house types in relationship to climate, how the sun, wind and seasonal changes shape the buildings. Along with Victor Olgyay’s essays in Design With Climate concerning regional design characteristics, I wanted to provide my students with a manual of types and case studies that they could reference throughout the course. This manual focuses on buildings in North America, specifically looking at historical examples, early modern houses and global multifamily housing in the 21st Century. Each of these precedents offer characteristics that should continue to inform the way we build today. Michael Crosby NOLA, 2010 “Five zones possess the sky which one is ever red from blazing sun ever burnt by fire.” Virgil CONTENTS Essay : Thin Buildings / Fat Buildings 1 Icons: Comparative Climate Analysis 6 Early American House Types 8 Essay : Winter Dress / Summer Dress 23 20th Century Case Studies 26 Sun Studies 43 Essay: 21st Century Strategies 51 Acknowledgements 54 Thin Buildings Fat Buildings A Bioclimatic Design Analysis All forms of life transform to adapt to their environment. -

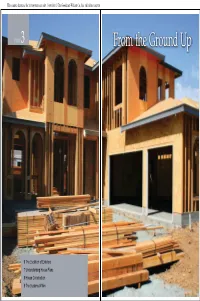

Chapter 6 the Evolution of Exteriors 165 PART 3 from the Ground Up

This sample chapter is for review purposes only. Copyright © The Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. All rights reserved. 164 Part 3 From the Ground Up Chapter 6 The Evolution of Exteriors 165 PART 3 From the Ground Up 6 The Evolution of Exteriors 7 Understanding House Plans 8 House Construction 9 The Systems Within This sample chapter is for review purposes only. Copyright © The Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. All rights reserved. 166 Part 3 From the Ground Up Chapter 6 The Evolution of Exteriors 167 CHAPTER 6 The Evolution of Exteriors Terms to Learn Arts and Crafts bungalow traditional International style folk ranch classic Contemporary style Early English earth-sheltered half-timbered Tidewater South Chapter Objectives New England Cape Cod After studying this chapter, you will be symmetrical able to dormer • summarize the development Saltbox of exterior architectural styles Garrison throughout history, including Spanish Traditional (both folk and classic), stucco Modern, and Contemporary house asymmetrical styles. Scandinavian • compare and contrast historical log cabin architectural and housing styles. gable roof German • summarize the value of historical pent roof preservation. Dutch Colonial gambrel roof Reading with Purpose French Normandy French Plantation As you read this chapter, write a letter to yourself. Imagine French Manor that you will receive this letter in a few years when you are Mansard roof working at your future job as an interior designer. What French Provincial key chapter points will be important to remember from this Georgian chapter? In the letter, list these points. hip roof Federal Adam style Early Classical Revival Greek Revival Southern Colonial Victorian Modern style Prairie style This sample chapter is for review purposes only.