Silver As a Drinking-Water Disinfectant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

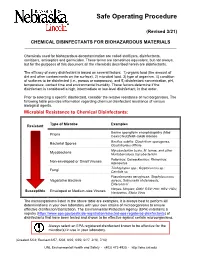

Chemical Disinfectants for Biohazardous Materials (3/21)

Safe Operating Procedure (Revised 3/21) CHEMICAL DISINFECTANTS FOR BIOHAZARDOUS MATERIALS ____________________________________________________________________________ Chemicals used for biohazardous decontamination are called sterilizers, disinfectants, sanitizers, antiseptics and germicides. These terms are sometimes equivalent, but not always, but for the purposes of this document all the chemicals described herein are disinfectants. The efficacy of every disinfectant is based on several factors: 1) organic load (the amount of dirt and other contaminants on the surface), 2) microbial load, 3) type of organism, 4) condition of surfaces to be disinfected (i.e., porous or nonporous), and 5) disinfectant concentration, pH, temperature, contact time and environmental humidity. These factors determine if the disinfectant is considered a high, intermediate or low-level disinfectant, in that order. Prior to selecting a specific disinfectant, consider the relative resistance of microorganisms. The following table provides information regarding chemical disinfectant resistance of various biological agents. Microbial Resistance to Chemical Disinfectants: Type of Microbe Examples Resistant Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (Mad Prions Cow) Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Bacillus subtilis; Clostridium sporogenes, Bacterial Spores Clostridioides difficile Mycobacterium bovis, M. terrae, and other Mycobacteria Nontuberculous mycobacterium Poliovirus; Coxsackievirus; Rhinovirus; Non-enveloped or Small Viruses Adenovirus Trichophyton spp.; Cryptococcus sp.; -

UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE PRODUCTION of VANILLIC ACID (SILVER, Oxide PROCESS) Irwin A

Patented Apr. 15, 1947 2,419,158 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE PRODUCTION OF VANILLIC ACID (SILVER, oxIDE PROCESS) Irwin A. Pearl, Appleton, Wis., assignor, by mesne assignments, to Sulphite Products Corporation, - Appleton, Wis., a corporation of Wisconsin No Drawing. Application January 12, 1944, Seria No. 517,985 8 Claims. (C. 260-521) 2 The present invention relates to the production About 300 parts of vanillic acid melting at 210 of vanillic and closely related acids, and to an 211 is obtained. - a improved process for producing acids derived by Ortho vanillin and syringaldehyde react in the oxidation from vanillin, Ortho-vanillin, and same way as the vanillin in Example I, with syringaldehyde. similarly high yields of completely transformed Most aldehydes may be transformed to the material. corresponding acids by common oxidizing agents If the treatment with solid sodium hydroxide or in the Cannizzaro reaction, but vanillin, Ortho warms the solution materially above 50° C., the vanillin, and Syringaldehyde are exceptions and vaniliin reacts as fast as it is added and the have been reported as not amenable to either temperature rises, but full completion of the reaction. Ordinary oxidizing agents either (1) action is assured by slight further heating. I have no action on the compound or (2) act as have secured good results with final temperatures dehydrogenating agents, and yield the dehydro of 75° to 85, but higher temperatures are dicompound or (3) cause complete decomposition. innocuous. The Cannizzaro reaction is conveniently written 5 However, if the materials are admixed at tem as follows: peratures materially below 50° C., it is first neces NaOH sary to warm them, and at about 50° C. -

Decontamination of Rooms, Medical Equipment and Ambulances Using an Aerosol of Hydrogen Peroxide Disinfectant B.M

Journal of Hospital Infection (2006) 62, 149–155 www.elsevierhealth.com/journals/jhin Decontamination of rooms, medical equipment and ambulances using an aerosol of hydrogen peroxide disinfectant B.M. Andersena,*, M. Rascha, K. Hochlina, F.-H. Jensenb, P. Wismarc, J.-E. Fredriksend aDepartment of Hospital Infection, Ulleva˚l University Hospital, Oslo, Norway bDivision of Pre-hospital Care, Ulleva˚l University Hospital, Oslo, Norway cDepartment of Medical Equipment, Ulleva˚l University Hospital, Oslo, Norway dHealth and Environment AS, Oslo, Norway Received 17 November 2004; accepted 1 July 2005 KEYWORDS Summary A programmable device (Sterinis, Gloster Sante Europe) Room decontamina- providing a dry fume of 5% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) disinfectant was tion; Ambulance tested for decontamination of rooms, ambulances and different types of decontamination; medical equipment. Pre-set concentrations were used according to the Medical equipment decontamination; volumes of the rooms and garages. Three cycles were performed with Hydrogen peroxide increasing contact times. Repetitive experiments were performed using fume decontamina- Bacillus atrophaeus (formerly Bacillus subtilis) Raven 1162282 spores to tion; Spore test control the effect of decontamination; after a sampling plan, spore strips were placed in various positions in rooms, ambulances, and inside and outside the items of medical equipment. Decontamination was effective in 87% of 146 spore tests in closed test rooms and in 100% of 48 tests in a surgical department when using three cycles. One or two cycles had no effect. The sporicidal effect on internal parts of the medical equipment was only 62.3% (220 tests). When the devices were run and ventilated during decontamination, 100% (57/57) of spore strips placed inside were decontaminated. -

Engineering a Model of the Earth As a Water Filter by Jonathon Kilpatrick, Nanette Marcum-Dietrich, John Wallace, and Carolyn Staudt

Copyright © 2018, National Science Teachers Association (NSTA). Reprinted with permission from Science and Children, Vol. 56, No. 3, October 2018. Engineering a Model of the Earth as a Water Filter By Jonathon Kilpatrick, Nanette Marcum-Dietrich, John Wallace, and Carolyn Staudt eaching students about the wa- from groundwater. Most is supplied smaller pieces lower down,” offered ter cycle is a staple of elemen- through public drinking water sys- one student. Another replied, “A lot of Ttary science instruction. When tems. But over 15 million families rely sand is mixing with the water though, asked to describe the water cycle, most on private, household wells and use and now it looks really dirty. Maybe students can quickly recite the contin- groundwater as their source of fresh sand should go first.” These conversa- ual cyclical process of condensation, water” (EPA 2016). Noting the im- tions continued throughout the design precipitation, and evaporation. But portance of infiltration in the water process. this simple definition misses the es- cycle and in the supply of essential By the end of the session, the stu- sential process of infiltration. Ground- groundwater led us to develop an engi- dents had constructed three filters. water and the process of infiltration, neering activity in which students are Two of them were stackable filters which cleans that water, are vital to our challenged to build a stackable filter with the water passing in turn through survival, but they are also hidden from using the Earth process of infiltration different layers and materials. The view and too often absent from our sci- as a model. -

Evaluating Disinfectants for Use Against the COVID-19 Virus

When it comes to choosing a disinfectant to combat the COVID-19 virus, research and health authorities suggest not all disinfectants are equally effective. The difference is in their active ingredient(s). HEALTH CANADA AND U.S. EPA ASSESSMENTS The work to evaluate disinfectants perhaps best starts with lists of approved disinfectants compiled by government health authorities. Health Canada has compiled a list of 85 hard surface disinfectant products (as of March 20, 2020) that meet their requirements for disinfection of emerging pathogens, including the virus that causes COVID-19. It can be accessed here. You can wade through the entire list. But if you locate the Drug Identification Number (DIN) on the disinfectant product label or the safety data sheet (SDS), then you can use the search function to quickly see if the product meets Health Canada requirements. A second list, updated on March 19, 2020, provides 287 products that meet the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) criteria for use against SARS-CoV-2, the novel coronavirus that causes the disease COVID-19. This list can be found here. Like the Health Canada list, you can wade through this one too. However, to best use this list, you should locate the U.S. EPA registration number on the product label or SDS, and use that number to search the list. The U.S. EPA registration number of a product consists of two sets of numbers separated by a hyphen. The first set of numbers refers to the company identification number, and the second set of numbers following the hyphen represents the product number. -

The Sport Berkey Portable Water Purifier – Generic Version

® The Sport Berkey Portable Water Purifier – Generic Version Sport Berkey® The Portable Water Purifier is the ideal personal protection traveling companion — featuring the IONIC ADSORPTION MICRO FILTRATION SYSTEM. The theory behind this innovation is simple. The bottle’s filter is designed to remove and/or dramatically reduce a vast array of health-threatening contaminants from questionable sources of water, including remote lakes and streams, stagnant ponds and water supplies in foreign countries where regulations may be sub standard, at best. Sport Berkey® The Portable Water Purifier Utilizes IONIC ADSORPTION MICRO FILTRATION This advanced technology was developed, refined, and proven through diligent, investigative research and testing performed by water purification specialists, researchers and engineers. The media within the filter element removes contaminants by a surface phenomenon known as “adsorption” which results from the molecular attraction of substances to the surface of the media. As the bottle is pressed, the source water is forced through the filter. The quality and volume of media used, determine the rate of adsorption. The flow rate or time of exposure through the filter has been calculated to yield the greatest volume removal of toxic chemicals caused by pollution from industry Sport Berkey® and agriculture. This exclusive filter also incorporates proprietary absorbing The Portable media that are impregnated into the micro-porous filter for the IONIC Water Purifier eliminates or absorption of pollutants into the filter such as aluminum, cadmium, reduces up to 99.9% of: chromium, copper, lead, mercury, and other dangerous heavy metals. • Harmful microscopic pathogens: The “Tortuous Path” structure of these pores gives it its unique E-coli (>99.99999%), Cryptosporidium, Sport Berkey® Giardia and other pathogenic bacteria. -

Comparative Study of Disinfectants for Use in Low-Cost Gravity Driven Household Water Purifiers Rajshree A

443 © IWA Publishing 2013 Journal of Water and Health | 11.3 | 2013 Comparative study of disinfectants for use in low-cost gravity driven household water purifiers Rajshree A. Patil, Shankar B. Kausley, Pradeep L. Balkunde and Chetan P. Malhotra ABSTRACT Point-of-use (POU) gravity-driven household water purifiers have been proven to be a simple, low- Rajshree A. Patil Shankar B. Kausley (corresponding author) cost and effective intervention for reducing the impact of waterborne diseases in developing Pradeep L. Balkunde Chetan P. Malhotra countries. The goal of this study was to compare commonly used water disinfectants for their TCS Innovation Labs – TRDDC, fi 54B, Hadapsar Industrial Estate, feasibility of adoption in low-cost POU water puri ers. The potency of each candidate disinfectant Pune - 411013, was evaluated by conducting a batch disinfection study for estimating the concentration of India E-mail: [email protected] disinfectant needed to inactivate a given concentration of the bacterial strain Escherichia coli ATCC 11229. Based on the concentration of disinfectant required, the size, weight and cost of a model purifier employing that disinfectant were estimated. Model purifiers based on different disinfectants were compared and disinfectants which resulted in the most safe, compact and inexpensive purifiers were identified. Purifiers based on bromine, tincture iodine, calcium hypochlorite and sodium dichloroisocyanurate were found to be most efficient, cost effective and compact with replacement parts costing US$3.60–6.00 for every 3,000 L of water purified and are thus expected to present the most attractive value proposition to end users. Key words | disinfectant, drinking water, E. -

Safer Disinfectant Use in Child Care and Schools During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Safer Disinfectant Use in Child Care and Schools During the COVID-19 Pandemic Vickie Leonard, PhD Environmental Health in Early Care and Educaon Project, Western States Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (WSPEHSU) 1 Why Should We Be Concerned about Environmental Health in ECE? 2 Why Should We Be Concerned about Environmental Health in ECE? • There are 8 million children in child care centers in the U.S. A child may spend up to 12,500 hours in an ECE facility. A million child care providers work in these centers in the U.S. Half are child-bearing age. • Many toxicants found in child care facilities are not addressed in state child care health and safety regulations. • No agency at the state or federal level is charged with ensuring children’s health and safety in and around schools and ECE facilities. • No systematic means exists for collecting data on environmental exposures in these buildings. • Teachers have more protection in these buildings (unions, OSHA) than children do 3 Why Should We Be Concerned about Environmental Health in ECE? • Many people think that adults and children are exposed to, and affected by, toxic chemicals in the same way. • This is not the case. • Children • have higher exposures to toxicants in the environment, • are more vulnerable to the effects of those toxicants than adults. 4 Cleaning and Disinfec?ng Products: A Major Source of Exposure in Child Care and Schools • Products used to clean, sanitize and disinfect child care facilities and schools are a good example of the pervasive and unregulated use of toxic chemicals that put the health of our children at risk. -

The Design and Creation of a Portable Water Purification System

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Honors Theses Undergraduate Research 2012 The Design and Creation of a Portable Water Purification System Adam Shull Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors Recommended Citation Shull, Adam, "The Design and Creation of a Portable Water Purification System" (2012). Honors Theses. 39. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors/39 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. John Nevins Andrews Scholars Andrews University Honors Program Honors Thesis The design and creation of a portable water purification system Adam Shull April 2, 2012 Advisor: Dr. Hyun Kwon Primary Advisor Signature: _____________________ Department: Engineering and Computer Science 2 Abstract A portable, low-power water purification system was developed for use by aid workers in underdeveloped world regions. The design included activated carbon and ceramic candle filtration to 0.2 microns for bacteria and turbidity reduction followed by UV irradiation for virus destruction. Flexibility and modularity were incorporated into the system with AC, DC, and environmental power supply options as well as the facility to purify water from either surface or local utility sources. Initial prototype testing indicated the successful filtration of methylene blue dye to well above the 75% UV transmittance level required for virus destruction by the UV reactor. -

Silver Nanoparticle Nanocomposite Filaments Produced by an In-Situ Reduction Reactive Melt Mixing Process

biomimetics Article Three-Dimensional Printed Antimicrobial Objects of Polylactic Acid (PLA)-Silver Nanoparticle Nanocomposite Filaments Produced by an In-Situ Reduction Reactive Melt Mixing Process Nectarios Vidakis 1, Markos Petousis 1,* , Emmanouel Velidakis 1, Marco Liebscher 2 and Lazaros Tzounis 3 1 Mechanical Engineering Department, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Estavromenos, 71004 Heraklion, Crete, Greece; [email protected] (N.V.); [email protected] (E.V.) 2 Institute of Construction Materials, Technische Universität Dresden, DE-01062 Dresden, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Ioannina, 45110 Ioannina, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2810-37-9227 Received: 14 August 2020; Accepted: 31 August 2020; Published: 2 September 2020 Abstract: In this study, an industrially scalable method is reported for the fabrication of polylactic acid (PLA)/silver nanoparticle (AgNP) nanocomposite filaments by an in-situ reduction reactive melt mixing method. The PLA/AgNP nanocomposite filaments have been produced initially + reducing silver ions (Ag ) arising from silver nitrate (AgNO3) precursor mixed in the polymer melt to elemental silver (Ag0) nanoparticles, utilizing polyethylene glycol (PEG) or polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), respectively, as macromolecular blend compound reducing agents. PEG and PVP were added at various concentrations, to the PLA matrix. The PLA/AgNP filaments have been used to manufacture 3D printed antimicrobial (AM) parts by Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF). The 3D printed PLA/AgNP parts exhibited significant AM properties examined by the reduction in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria viability (%) experiments at 30, 60, and 120 min duration of contact (p < 0.05; p-value (p): probability). -

Designing a Low-Cost Ceramic Water Filter Press

International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 62-77, Spring 2013 ISSN 1555-9033 Designing a Low-Cost Ceramic Water Filter Press Michael Henry BS, Immunology and Infectious Disease The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802 [email protected] Siri Maley BS, Mechanical Engineering The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802 [email protected] Khanjan Mehta* Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship (HESE) Program The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802 [email protected] *Corresponding Author Abstract -- Diarrheal diseases due to unsanitary water are a leading cause of death in low- and middle- income countries. One potential solution to this problem is widespread access to point-of-use ceramic water filters made from universally-available materials. This increased access can be achieved by empowering local artisans to initiate self-sustaining and scalable entrepreneurial ventures in their communities. However, a major barrier to the start-up of these businesses is the prohibitively expensive press used to form the filters. This article reviews filter press technologies and identifies specific functional requirements for a suitable and affordable filter press. Early-stage field-testing results of a proof-of- concept design that can be manufactured by two people in two days at one-tenth of the cost of popular filter presses is presented. Index Terms - Ceramic Water Filter, Filter Press, Filtration, Global Health INTRODUCTION The water crisis -

Controlled Growth of Silver Oxide Nanoparticles on the Surface of Citrate Anion Intercalated Layered Double Hydroxide

nanomaterials Article Controlled Growth of Silver Oxide Nanoparticles on the Surface of Citrate Anion Intercalated Layered Double Hydroxide Do-Gak Jeung 1, Minseop Lee 2, Seung-Min Paek 2,* and Jae-Min Oh 1,* 1 Department of Energy and Materials Engineering, Dongguk University-Seoul, Seoul 04620, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Chemistry, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 41566, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.-M.P.); [email protected] (J.-M.O.) Abstract: Silver oxide nanoparticles with controlled particle size were successfully obtained utilizing citrate-intercalated layered double hydroxide (LDH) as a substrate and Ag+ as a precursor. The lattice of LDH was partially dissolved during the reaction by Ag+. The released hydroxyl and citrate acted as a reactant in crystal growth and a size controlling capping agent, respectively. X-ray diffraction, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, and microscopic measurements clearly showed the development of nano-sized silver oxide particles on the LDH surface. The particle size, homogeneity and purity of silver oxide were influenced by the stoichiometric ratio of Ag/Al. At the lowest silver ratio, the particle size was the smallest, while the chemical purity was the highest. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and UV-vis spectroscopy results suggested that the high Ag/Al ratio tended to produce silver oxide with a complex silver environment. The small particle size and homogeneous distribution of silver oxide showed advantages in antibacterial efficacy compared with bulk silver oxide. LDH Citation: Jeung, D.-G.; Lee, M.; Paek, with an appropriate ratio could be utilized as a substrate to grow silver oxide nanoparticles with S.-M.; Oh, J.-M.