Ten Views of a Landslip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal-Management-Policy-In-Purbeck-Jan2021 V1

Coastal Adaption Strategy, January 2021 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Coastal Management in Purbeck ....................................................................................... 3 Annual review and priority actions for 2021 ........................................................................... 4 Looking back on 2020… ...................................................................................................................... 4 Priority actions for 2021… ................................................................................................................... 4 2. Background .................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Shifting Shores .................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Shoreline Management Plans ............................................................................................ 6 2.3 Climate Change and the Coast ........................................................................................... 7 2.4 Communication and Engagement Strategy ....................................................................... 8 2.5 Coastal Monitoring ............................................................................................................ 8 3. Our strategy for the Purbeck coast ............................................................................... -

Tunnels, Deeper, Freefall, and Closer by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams

READING GROUP GUIDE Tunnels, Deeper, Freefall, and closer by Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams Enter the terrifying world of Tunnels—a subterranean society under the streets of modern London, whose citizens are enslaved by a strange, cruel sect, the Styx, who plan to exterminate all Topsoilers. Can fourteen-year-old Will defeat the Styx, and rescue his missing father? Roderick Gordon and Brian Williams first met at college in London and have remained friends ever since. Gordon, a former investment banker, now lives with his wife and children in Norfolk, England; Williams, an installation artist, inhabits the city’s Hackney neighborhood, accompanied everywhere by his invisible dog. About their writing process, Gordon says: “When I lived in London, my house was only a ten-minute bike ride from where Brian lived, so he’d cycle round and we would work on Tunnels at my kitchen table. When I moved with my family to the country, we discussed Deeper over many late-night phone calls, and swapped sections by email. When I visit London we go to a couple of favorite cafés. They’ve gotten used to us and know that we can make a cup of coffee last several hours!” Tunnels A New York Times Bestseller About the book He’s a loner at school, his sister’s beyond bossy, and his mother watches TV all day long, but at least Will Burrows shares one hobby with his otherwise weird father: They’re both obsessed with archeological sites. When the two discover an abandoned tunnel buried below modern London, they think they’re on the brink of a major find. -

Download Highfield Mole, Book 1, , Roderick Gordon, Brian Williams

Highfield Mole, Book 1, , Roderick Gordon, Brian Williams, Mathew & Son Limited, 2005, 0954839900, 9780954839901, . DOWNLOAD http://archbd.net/17MYMtN Freefall , Roderick Gordon, Brian James Williams, Feb 1, 2010, , 599 pages. As 14-year-old archaeologist Will and his friends plummet down a subterranean pore, they face deadly creatures and discover a strange fungal shelf, which not only holds .... The Battle for God , Karen Armstrong, 2001, Religion, 442 pages. Reveals how the fundamentalist movements in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam were born out of a dread of modernity.. John Carter of Mars , Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1964, Carter, John (Fictitious character), 157 pages. All the classic works in the John Carter series are featured here.. Boy Zero Wannabe Hero The Attack of the Brain-Dead Breakdancing Zombies, Peter Millett, Nov 1, 2010, , 144 pages. General Pandemonium’s back and he’s badder than ever.Disguised as pop singer Andy Dandy he’s out to brainwash the world with his hypnotic songs and turn everyone into a bunch .... The Caretaker and The Dumb Waiter Two Plays, Harold Pinter, 1988, Drama, 121 pages. The text of Pinter's two plays, depicting the terrors of everyday life. both of which were performed in London during 1960. Developing Trends Under the Consumer Product Safety Act , Irving Scher, 1974, Product safety, 296 pages. Wannabe , Melanie Spears, Aug 1, 2000, Juvenile Nonfiction, 160 pages. Offers a behind-the-scenes look at some of the most powerful and glamorous jobs in the world, such as sports legend and super model, along with helpful advice, true stories ... -

The National Trust February 2019

Shell Bay, Studland The National Trust February 2019 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background .................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Shifting Shores .................................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Shoreline Management Plans .......................................................................................... 5 2.3 Climate Change and the Coast ............................................................................................. 6 2.4 Communication and Engagement Strategy ...................................................................... 7 2.5 Coastal Monitoring ........................................................................................................... 7 3. Coastal Management Policy Description ........................................................................ 8 3.1 Middlebere Peninsula .................................................................................................... 10 3.2 Brands Bay and Bramble Bush Bay ................................................................................. 12 3.3 South Haven Point .......................................................................................................... 13 3.4 Shell Bay ........................................................................................................................ -

Geological Sights! Southwest England Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society

Geological Sights! Southwest England Harrow and Hillingdon Geological Society @GeolAssoc Geologists’ Association www.geologistsassociation.org.uk Southwest England Triassic Mercia Mudstone & Penarth Groups (red & grey), capped with Early Jurassic Lias Group mudstones and thin limestones. Aust Cliff, Severn Estuary, 2017 Triassic Mercia Mudstone & Penarth Groups, with Early Jurassic Lias Group at the top. Looking for coprolites Gypsum at the base Aust Cliff, Severn Estuary, 2017 Old Red Sandstone (Devonian) Portishead, North Somerset, 2017 Carboniferous Limestone – Jurassic Inferior Oolite unconformity, Vallis Vale near Frome Mendip Region, Somerset, 2014 Burrington Oolite (Carboniferous Limestone), Burrington Combe Rock of Ages, Mendip Hills, Somerset, 2014 Whatley Quarry Moon’s Hill Quarry Carboniferous Limestone Silurian volcanics Volcaniclastic conglomerate in Moon’s Hill Quarry Mainly rhyodacites, andesites and tuffs - England’s only Wenlock-age volcanic exposure. Stone Quarries in the Mendips, 2011 Silurian (Wenlock- age) volcaniclastic conglomerates are seen here above the main faces. The quarry’s rock types are similar to those at Mount St Helens. Spheroidal weathering Moons Hill Quarry, Mendips, Somerset, 2011 Wave cut platform, Blue Lias Fm. (Jurassic) Kilve Mercia Mudstone Group (Triassic) Kilve St Audrie’s Bay West Somerset, 2019 Watchet Blue Lias Formation, Jurassic: Slickensiding on fault West Somerset, 2019 Triassic, Penarth Group Triassic, Mercia Mudstone Blue Anchor Fault, West Somerset, 2019 Mortehoe, led by Paul Madgett. Morte Slates Formation, Devonian (Frasnian-Famennian). South side of Baggy Point near Pencil Rock. Ipswichian interglacial dune sands & beach deposit (125 ka) upon Picton Down Mudstone Formation (U. Devonian) North Devon Coast, 1994 Saunton Down End. ‘White Rabbit’ glacial erratic (foliated granite-gneiss). Baggy Headland south side. -

Higher Geography

LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES MARINE EROSION PROCESSES. Read the course booklet. You will need to know and be able to explain the four methods of coastal erosion and two of weathering The next few slides illustrate these processes. 1 LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES Hydraulic Action The force of waves hitting a cliff (or sea wall) compresses water and air into cracks and joints. This increase in pressure may lead to cracks widening and pieces of rock breaking off. 2 LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES Abrasion Rock fragments may be picked up by waves and thrown against the rock face of cliffs by subsequent waves. Sometimes the softer strata are abraded more than the harder ones, giving a striped appearance. Abrasion is most effective at the base of cliffs. 3 LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES Wave attrition Rock fragments are worn down into smaller and more rounded pieces. Currents and tidal movements cause the fragments to be swirled around and to grind against each other. This type of erosion produces pebble beaches. 4 LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES Water- layer weathering Alternative wetting and drying -as happens with the rise and fall of the tides -can disintegrate porous or coarser rock layers. Salt crystals growing in rock spaces can do the same thing. 5 LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES Corrosion (solution) Salts and acids in sea water can react with rocks , slowly dissolving them away. 6 LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES Rates of erosion depend on many factors: Waves – strength, frequency, height Weather – frequency of storm conditions Geology of the coastline : -type of rock -orientation of stratification (the way the bedding planes in the rock face the sea) 7 LITHOSPHERE CORE COASTLINES The FETCH is the distance travelled by waves from one shore to another. -

Somersetshire Archzeological Natural History Societys Proceedings, 1871

S O ME R S E TS H I R E A R C H ZE O L OG I C A L NA TUR A L H I STO R Y ’ SO C I E T Y S PR O C E E D I N G S 1 8 1 , 7 I VO L . XVI T A U N T O N S T F R E D E R I C K M A Y , H I G H T R E E L O NDO N : L O NG MA NS G R E EN R EA DER A ND D Y ER M DC C C L XXI I 1 400 91 3 The followin g Illustrations have been presented to the ociety W H . The Monument to Sir John de Dummer, by . H el ar . f m y , Esq , of Coker Court ; and the Seals o Du mer, B d . by Thomas on , Esq , of Tyneham . u an M t ts . P R O C E E D I N G S . G w 1 8 71 eneral Meeting at Cre kerne, Report of Council Financial Statement m E A . A . s . Inaugural ddress by E Free an, q W . H . i E s . ells Cathedral Statutes , by F D ckinson, q Public Records in the County of Somerset, by T Mr . S erel - . on Pi C The Evening Meeting, Mr Pooley, g ross A . J . B ncient Embroidered Copes, by Mr C uckley Excursion : Montacute H ouse - - H ambdon Montacute Church, Stoke sub H H R r ev . -

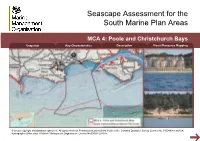

Poole and Christchurch Bays Snapshot Key Characteristics Description Visual Resource Mapping

Seascape Assessment for the South Marine Plan Areas MCA 4: Poole and Christchurch Bays Snapshot Key Characteristics Description Visual Resource Mapping © Crown copyright and database right 2013. All rights reserved. Permission Number Defra 012012.003. Contains Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100049981 and UK Hydrographic Office data. © Marine Management Organisation. Licence No EK001-201188. MCA 4: Poole and Christchurch Bays Overall cShnaarpaschteort Key Characteristics Description Visual Resource Mapping Location and boundaries This Marine Character Area (MCA) covers the coastline from Peveril Point in the west to the eastern fringes of Milford on Sea in the east, covering the whole of Poole and Christchurch Bays. Its seaward boundary with The Solent (MCA 5) is formed by the change in sea and tidal conditions upon entry into the Needles Channel. In the west, the coastal/seaward boundary with MCA 3 follows the outer edge of the Purbeck Heritage Coast. The Character Area extends to a maximum distance of approximately 40 kilometres (22 nautical miles) offshore, ending at the northern extent of the Wight-Barfleur Reef candidate offshore SAC (within MCA 14). Please note that the MCA boundaries represent broad zones of transition (not immediate breaks in character). Natural, visual, cultural and socio- economic relationships between adjacent MCAs play a key role in shaping overall character. Therefore individual MCAs should not be considered in isolation. Overall character This MCA is dominated in the west by the busy port of Poole Harbour, which is a hive of marine-based activity as well as an internationally important wildlife refuge. The more tranquil Christchurch Harbour sits beyond the protruding Hengistbury Head, which separates the two bays. -

Poole Bay, Poole Harbour and Wareham Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management

Poole Bay, Poole Harbour and Wareham Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Final Strategy December 2014 Aerial photo credit: Kitchenham Ltd 1 Foreword ‘The Poole and Wareham ‘I am pleased to be able to Strategy area is one of the support this Flood and most vibrant and diverse Coastal Erosion Risk sections of coast in England. Management Strategy, and to The range of cultural, social, thoroughly recommend that all archaeological, biodiversity members of our coastal and landscape features leads communities make to high value and high themselves aware of the sensitivity when considering issues that we face going into potential changes. The Flood the future. The effects of and Coastal Erosion Risk climate change are Management Strategy is challenging to predict, but the progressing towards formal best way for us to protect the adoption under the things we value as a society is stewardship of a Steering to engage with the issues and Group which includes the add our voices to the strategic Local Authorities, Port decisions. The comments Authority and Conservation that have been received Groups, representing the strengthen this Strategy which different interests and will shape the future of our ensuring that the future of the coast.’ Wareham and Poole area is sustainable for the next 20, 50 Andy Bradbury and 100 years. The Strategy Chair Southern Coastal Group has built on the existing Catchment Flood Management Plans, Shoreline Management Plans and the comments from organisations and members of the public.’ Alan Lovell Chair Wessex Regional -

Boscobel Or, the Royal Oak

Boscobel or, the Royal Oak William Harrison Ainsworth Boscobel or, the Royal Oak Table of Contents Boscobel or, the Royal Oak......................................................................................................................................1 William Harrison Ainsworth..........................................................................................................................1 Book the first: the Battle of Worcester.......................................................................................................................4 Chapter 1. HOW CHARLES THE SECOND ARRIVED BEFORE WORCESTER, AND CAPTURED A FORT, WHICH HE NAMED FORT ROYAL ..............................................................4 Chapter 2. SHOWING HOW THE MAYOR OF WORCESTER AND THE SHERIFF WERE TAKEN TO UPTON−ON−SEVERN, AND HOW THEY GOT BACK AGAIN.....................................10 Chapter 3. HOW CHARLES MADE HIS TRIUMPHAL ENTRY INTO WORCESTER; AND HOW HE WAS PROCLAIMED BY THE MAYOR AND SHERIFF OF THAT LOYAL CITY......................14 Chapter 4. HOW CHARLES WAS LODGED IN THE EPISCOPAL PALACE; AND HOW DOCTOR CROSBY PREACHED BEFORE HIS MAJESTY IN THE CATHEDRAL...........................17 Chapter 5. HOW CHARLES RODE TO MADRESFIELD COURT; AND HOW MISTRESS JANE LANE AND HER BROTHER, WITH SIR CLEMENT FISHER, WERE PRESENTED TO HIS MAJESTY...................................................................................................................................................20 Chapter 6. HOW CHARLES ASCENDED THE WORCESTERSHIRE -

Flat 1, the Pinnacles, 2 the Parade, Swanage £385,000

FLAT 1, THE PINNACLES, 2 THE PARADE, SWANAGE £385,000 LEASEHOLD This spacious maisonette comprises the entire ground floor and lower ground floor of a substantial terraced building located in a private position on The Parade, directly overlooking Swanage Bay and about 200 metres from the main shopping thoroughfare. The accommodation is tastefully decorated with a neutral decor maximising the light and overall spatial feeling. On the foreshore, it offers character coastal living with carved ornate fireplace, high ceilings with embellished cornicing and wood flooring to the ground floor. The property is thought to have been constructed around the turn of the 20th Century and has frontal elevations of part Purbeck stone, the remainder being brick, under an imitation slate roof. The seaside town of Swanage lies at the Eastern tip of the Isle of Purbeck, delightfully situated between the Purbeck Hills. It has a safe, sandy beach, and is an attractive mixture of old stone cottages and more modern properties, all of which blend in well with the peaceful surroundings. To the South is the Durlston Country Park renowned for being the gateway to the Jurassic Coast and World Heritage Coastline. The market town of Wareham is some 9 miles away and has main line rail link to London Waterloo (about 2.5 hours). Viewing is strictly by appointment through the Sole Agents, Corbens, 01929 422284. Postcode for SATNAV BH19 1DA. Property Ref: PAR1231 Council Tax Band C The finest feature of this split level apartment has to be the generously sized living/dining room with large bay window overlooking the bay giving outstanding panoramic views to Ballard Down. -

The Distribution of the Foraminiferida in the Albian and Cenomanian of S.W. England. by M.B. Hart, B.So., F.C.S. Thesis Submitt

The Distribution of the Foraminiferida in the Albian and Cenomanian of S.W. England. by M.B. Hart, B.So., F.C.S. VOL Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London. February 1970. 2 Abstract An attempt has been made at resolving some of the difficulties of British mid—Cretaceous stratigraphic correlation using Foraminiferida. Over six hundred samples have been collected from all the major Albian and Cenomanian sections in south and south west England and these have been processed for their foraminiferal content. Over two hundred species and varieties from eighty six genera have been documented, many for the first time. These fossils have been used in the ratification of a zonal scheme and as a testing ground for a correlation technique based on the varying proportions of planktonic and benthonic individuals in each sample. The results of these investigations have demonstrated the value of Foraminiferida in the solution of stratigraphic problems, and as a result of this a new correlation scheme for the Albian and Cenomanian of southern England has been tentatively suggested. The Albian/Cenomanian and Cenomanian/Turonian boundaries have also been determined in the British lithological successions and characteristic faunas for each stage outlined. The main feature of stratigraphic interest has been the determination of a period of mid,-Cenomanian folding and its resulting affect on the stratigraphy. 3 Table of Contents page Abstract 2 Table of Contents 3 Index of Figures 4 Index of Text Plates 5 Index of Plates 6 Index of Enclosures 7 Acknowledgements 8 Chapter 1.