1 Performing Gender in the Studio and Postmodern Musical Michael

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

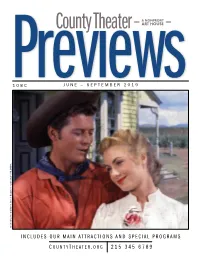

County Theater ART HOUSE

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Judy Garland (1922-1969)

1/22 Data Judy Garland (1922-1969) Pays : États-Unis Sexe : Féminin Naissance : Grand-Rapid (S. D.), 10-06-1922 Mort : Londres, 22-01-1969 Note : Chanteuse et actrice américaine Autre forme du nom : Frances Gumm (1922-1969) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0000 8380 6106 (Informations sur l'ISNI) Judy Garland (1922-1969) : œuvres (255 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres audiovisuelles (y compris radio) (45) "Un enfant attend. - [2]" "Un enfant attend. - [2]" (2016) (2016) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le magicien d'Oz" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2013) (2013) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "La jolie fermière" "Till the clouds roll by" (2013) (2012) de George Wells et autre(s) de Richard Whorf et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "Meet me in St. Louis. - Vincente Minnelli, réal.. - [2]" (2012) (2012) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "La pluie qui chante. - Richard Whorf, réal.. - [2]" (2011) (2010) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de George Wells et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur data.bnf.fr 2/22 Data "Le chant du Missouri" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2009) (2009) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "The pirate" "La danseuse des Folies Ziegfeld" (2008) (2007) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Sonya Levien et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Parade de printemps" "Un enfant attend. -

The Marilyn Monroe Collection at May Fair Bar Limited-Edition Cocktail

The Marilyn Monroe Collection at May Fair Bar Limited-edition cocktail menu and exclusive dinner screenings in celebration of Marilyn Monroe’s legendary costumes display, ahead of their sale at Julien’s Auctions This autumn, celebrate one of Hollywood’s most iconic starlets with an exclusive display of JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE LIFE AND CAREER OF MARILYN MONROE at The May Fair, A Radisson Collection Hotel. A unique cocktail menu at May Fair Bar and a series of indulgent dinner screenings of her most famous roles will run in conjunction with the exclusive viewing of the Hollywood legend’s costumes and clothing from 24th September to 21st October 2019. Four outfits that Marilyn Monroe wore in her films and press conferences will be on view in the celebrated London hotel The May Fair ahead of their sale by the acclaimed auction house Julien’s Auctions. The dresses on display are from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, There’s No Business Like Show Business, River of No Return and Some Like It Hot and will be sold live on 1st November at Julien’s Auctions at The Standard Oil Building in Beverly Hills at 1pm PT (8pm GMT) and online at www.juliensauctions.com. The Marilyn Monroe Collection cocktail menu will consist of four original drinks created by May Fair Bar’s award-winning team, each inspired by one of the four outfits exclusively on display in the hotel. Enjoy the finer things with Lorelei Lee, a luxurious mix of Courvoisier VSOP, Moët & Chandon Brut, Cabernet Sauvignon & cherry reduction and Champagne foam inspired by 1953’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, or dive into the flavours of the old West with Kay Weston from River of No Return, made with Bombay Sapphire gin, saffron syrup, orange blossom honey, lemon & Fever-Tree Mediterranean tonic. -

The Honorable Mentions Movies- LIST 1

The Honorable mentions Movies- LIST 1: 1. A Dog's Life by Charlie Chaplin (1918) 2. Gone with the Wind Victor Fleming, George Cukor, Sam Wood (1940) 3. Sunset Boulevard by Billy Wilder (1950) 4. On the Waterfront by Elia Kazan (1954) 5. Through the Glass Darkly by Ingmar Bergman (1961) 6. La Notte by Michelangelo Antonioni (1961) 7. An Autumn Afternoon by Yasujirō Ozu (1962) 8. From Russia with Love by Terence Young (1963) 9. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors by Sergei Parajanov (1965) 10. Stolen Kisses by François Truffaut (1968) 11. The Godfather Part II by Francis Ford Coppola (1974) 12. The Mirror by Andrei Tarkovsky (1975) 13. 1900 by Bernardo Bertolucci (1976) 14. Sophie's Choice by Alan J. Pakula (1982) 15. Nostalghia by Andrei Tarkovsky (1983) 16. Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders (1984) 17. The Color Purple by Steven Spielberg (1985) 18. The Last Emperor by Bernardo Bertolucci (1987) 19. Where Is the Friend's Home? by Abbas Kiarostami (1987) 20. My Neighbor Totoro by Hayao Miyazaki (1988) 21. The Sheltering Sky by Bernardo Bertolucci (1990) 22. The Decalogue by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1990) 23. The Silence of the Lambs by Jonathan Demme (1991) 24. Three Colors: Red by Krzysztof Kieślowski (1994) 25. Legends of the Fall by Edward Zwick (1994) 26. The English Patient by Anthony Minghella (1996) 27. Lost highway by David Lynch (1997) 28. Life Is Beautiful by Roberto Benigni (1997) 29. Magnolia by Paul Thomas Anderson (1999) 30. Malèna by Giuseppe Tornatore (2000) 31. Gladiator by Ridley Scott (2000) 32. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring by Peter Jackson (2001) 33. -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love You 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 911 More Than A Woman 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You Ariana Grande Dangerous Woman "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Eat It "Weird Al" Yankovic White & Nerdy *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC (God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You *NSYNC I'll Never Stop *NSYNC It's Gonna Be Me *NSYNC No Strings Attached *NSYNC Pop *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart *NSYNC That's When I'll Stop Loving You *NSYNC This I Promise You *NSYNC You Drive Me Crazy *NSYNC I Want You Back *NSYNC Feat. Nelly Girlfriend £1 Fish Man One Pound Fish 101 Dalmations Cruella DeVil 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Mandy 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 10cc Don't Turn Me Away 10cc Feel The Love 10cc Food For Thought 10cc Good Morning Judge 10cc Life Is A Minestrone 10cc One Two Five 10cc People In Love 10cc Silly Love 10cc Woman In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 2nd Baptist Church (Lauren James Camey) Rise Up 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Call Dam Bids on December 10, Is Plan

LEADING A lAVE ADVERTISING NEWSPAPER IN A MEDIUM Coulee City Dispatch PROGREBSIVE OWHR VOLUME XXVI—NUMBER 16 COULEE CITY, GRANT COUNTY, WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, PCT. 21, 1937 SUBSCRIPTION $1.50 PER YEAR Call Dam Bids on December 10, Is Plan Huge Oil Fraud Charged as At the Russian Polar Base Tentative Date Grand Jury Indicts Eleven Set by Page former and sal- Eleven officers CARD [PARTY SATURDAY ' December 10 was tentatively esmen for the Peoples Gas and set today for opening of bids for Ofl comipany and associated ‘com- for the card The date Rebekah completion of Grand Coulee dam. paniesz were indicted by a federal party changed from Fri- has been - The bids will be opened ip the district court grand jury at Taco- day until Saturday night, it was assembly hall of the Chamber of ma Yyesterday for mail fraud, vio- announced today. The change was Commerce. lation of the federal securities act that made when it was learned Announcment lof the bid opening and congpiracy. was Sat- no dance scheduled for was made in Washington, D, C, to- The complaint involved business urday night to the conflict with day by John C. Page, federal of the Peoples Gas and Oil com- com- affair. missioner (of reclamation. pany, by which it clgijmed the Prizes will be awarded winners was * “A lot depends on when we, com- de’endants have .collected more and a supper served following the plete the specifications,” Page than $1,881,000 from Washington pinochle session. ’Mir. recidents. said, ‘“The contractors should have at least six weeks to look them Denfendants Named ROAD JOBS AWARDED f over and make their estimates Joseph F. -

Marilyn Monroe, Lived in the Rear Unit at 5258 Hermitage Avenue from April 1944 to the Summer of 1945

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC-2015-2179-HCM ENV-2015-2180-CE HEARING DATE: June 18, 2015 Location: 5258 N. Hermitage Avenue TIME: 10:30 AM Council District: 2 PLACE: City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: North Hollywood – Valley Village 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: South Valley Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Valley Village 90012 Legal Description: TR 9237, Block None, Lot 39 PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the DOUGHERTY HOUSE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER(S): Hermitage Enterprises LLC c/o Joe Salem 20555 Superior Street Chatsworth, CA 91311 APPLICANT: Friends of Norma Jean 12234 Chandler Blvd. #7 Valley Village, CA 91607 Charles J. Fisher 140 S. Avenue 57 Highland Park, CA 90042 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. NOT take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation do not suggest the submittal warrants further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. MICHAEL J. LOGRANDE Director of Planning [SIGN1907 [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Shannon Ryan, City Planning Associate Office of Historic Resources Attachments: Historic-Cultural Monument Application CHC-2015-2179-HCM 5258 N. Hermitage, Dougherty House Page 2 of 3 SUMMARY The corner property at 5258 Hermitage is comprised of two one-story buildings. -

Lorna Luft Next to Take the Stage at Live at the Orinda Theatre, Oct. 4

LAMORINDA WEEKLY | Lorna Luft next to take the stage at Live at the Orinda Theatre, Oct. 4 Published Octobwer 3rd, 2018 Lorna Luft next to take the stage at Live at the Orinda Theatre, Oct. 4 By Derek Zemrak Lorna Luft was born into Hollywood royalty, the daughter of Judy Garland and film producer Sidney Luft ("A Star is Born"). She will be bringing her musical talent to the Orinda Theatre at 7:30 p.m. Oct. 4 as part of the fall concert series, Live at the Orinda, where she will be singing the songs her mother taught her. Luft's acclaimed career has encompassed virtually every arena of entertainment. A celebrated live performer, stage, film and television actress, bestselling author, recording artist, Emmy-nominated producer, and humanitarian, she continues to triumph in every medium with critics labeling her one of the most versatile and exciting artists on the stage today. The daughter of legendary entertainer Garland and producer Luft, music and entertainment have always been integral parts of her life. Luft is a gifted live performer, frequently featured on the Lorna Luft Photos provided world's most prestigious stages, including The Hollywood Bowl, Madison Square Garden, Carnegie Hall, The London Palladium, and L'Olympia in Paris. She proves again and again that she's a stellar entertainer, proudly carrying the torch of her family's legendary show business legacy. "An Evening with Lorna Luft: Featuring the Songbook of Judy Garland" is a theatrical extravaganza that melds one of the world's most familiar songbooks with personal memories of a loving daughter. -

032343 Born Yesterday Insert.Indd

among others. He is a Senior Fight Director with OUR SPONSORS ABOUT CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY Dueling Arts International and a founding member of Dueling Arts San Francisco. He is currently Chevron (Season Sponsor) has been the Center REP is the resident, professional theatre CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY teaching combat related classes at Berkeley Rep leading corporate sponsor of Center REP and company of the Lesher Center for the Arts. Our season Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director School of Theatre. the Lesher Center for the Arts for the past nine consists of six productions a year – a variety of musicals, LYNNE SOFFER (Dialect Coach) has coached years. In fact, Chevron has been a partner of dramas and comedies, both classic and contemporary, over 250 theater productions at A.C.T., Berkeley the LCA since the beginning, providing funding that continually strive to reach new levels of artistic presents Rep, Magic Theatre, Marin Theater Company, for capital improvements, event sponsorships excellence and professional standards. Theatreworks, Cal Shakes, San Jose Rep and SF and more. Chevron generously supports every Our mission is to celebrate the power of the human Opera among others including ten for Center REP. Center REP show throughout the season, and imagination by producing emotionally engaging, Her regional credits include the Old Globe, Dallas is the primary sponsor for events including Theater Center, Arizona Theatre Company, the intellectually involving, and visually astonishing Arena Stage, Seattle Rep and the world premier the Chevron Family Theatre Festival in July. live theatre, and through Outreach and Education of The Laramie Project at the Denver Center.