Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THOUSAND MILE SONG Also by David Rothenberg

THOUSAND MILE SONG Also by David Rothenberg Is It Painful to Think? Hand’s End Sudden Music Blue Cliff Record Always the Mountains Why Birds Sing THOUSAND MILE SONG Whale Music In a Sea of Sound DAVID ROTHENBERG A Member of the Perseus Books Group New York Copyright © 2008 by David Rothenberg Published by Basic Books, A Member of the Perseus Books Group All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016–8810. Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255–1514, or e-mail [email protected]. Designed by Linda Mark Set in 12 pt Granjon by The Perseus Books Group Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rothenberg, David, 1962- Thousand mile song: whale music in a sea of sound / David Rothenberg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-465-07128-9 (alk. paper) 1. Whales—Behavior. 2. Whale sounds. I. Title. QL737.C4R63 2008 599.5’1594—dc22 2007048161 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS 1 WE DIDN’T KNOW, WE DIDN’T KNOW: Whale Song Hits the Charts 1 2GONNA GROW -

“The Dying of the Light”

“The Dying of the Light” How Common Core No. 113 Damages Poetry Instruction April 2014 A Pioneer Institute White Paper by Anthony Esolen, Jamie Highfill, and Sandra Stotsky Pioneer’s Mission Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data- driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government. Pioneer’s Centers This paper is a publication of the Center for School Reform, which seeks to increase the education options available to parents and students, drive system-wide reform, and ensure accountability in public education. The Center’s work builds on Pioneer’s legacy as a recognized leader in the charter public school movement, and as a champion of greater academic rigor in Massachusetts’ elementary and secondary schools. Current initiatives promote choice and competition, school- based management, and enhanced academic performance in public schools. The Center for Better Government seeks limited, accountable government by promoting competitive delivery of public services, elimination of unnecessary regulation, and a focus on core government functions. Current initiatives promote reform of how the state builds, manages, repairs and finances its transportation assets as well as public employee benefit reform. The Center for Economic Opportunity seeks to keep Massachusetts competitive by promoting a healthy business climate, transparent regulation, small business creation in urban areas and sound environmental and development policy. Current initiatives promote market reforms to increase the supply of affordable housing, reduce the cost of doing business, and revitalize urban areas. -

From Silver Apples of the Moon to a Sky of Cloudless Sulphur: V Morton Subotnick & Lillevan 2015 US, Europe & JAPAN

From Silver Apples of the Moon to A Sky of Cloudless Sulphur: V Morton Subotnick & Lillevan 2015 US, Europe & JAPAN February 3 – 7 Oakland, California Jean Macduff Vaux ComposerinResidence at Mills College February 7 Oakland, California Mills College, Littlefield Concert Hall March 7 Moscow Save Festival at Arma March 4 New York the Kitchen: SYNTH Nights May Tel-Aviv, Israel Vertigo Dance Company June 7 London Cafe Oto June 16 Tel-Aviv, Israel Israel Museum June 20 Toronto Luminato Festival/Unsound Toronto July 28 Berlin Babylon Mitte (theatre) September 11 Tokyo TodaysArt.JP Tokyo September 12 Yamaguchi YCAM September 20 Kobe TodaysArt.JP Kobe November 22 Washington, DC National Gallery of Art 1 Morton Subotnick 2015 Other Events photo credit: Adam Kissick for RECORDINGS WERGO released in June 2015 After the Butterfly The Wild Beasts http://www.schott-music.com/news/archive/show,11777.html?newsCategoryId=19 Upcoming re-releases from vinyl on WERGO Fall 2015: Axolotl, Joel Krosnick, cello A Fluttering of Wings with the Juilliard Sting Quartet Ascent into Air from Double life of Amphibians The Last Dream of the Beat for soprano, Two Celli and Ghost electronics; Featuring Joan La Barbara, soprano Upcoming Mode Records: Complete Piano Music of Morton Subotnick The Other Piano, Liquid Strata, Falling Leaves and Three Piano Preludes. Featuring SooJin Anjou, pianist Release of a K-6 online music curriculum: Morton Subotnicks Music Academy https://musicfirst.com/msma 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM INFO Pg 4 CONCERT LISTING AND BIOS Pg 5 CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pg 6 PRESS PHOTOS Pg 8 AUDIO AND VIDEO LINKS Pg 13 PRESS QUOTES Pg 15 TECH RIDER Pg 19 3 PROGRAM INFO TITLE OF WORK TO BE PRESENTED From Silver Apples of the Moon to A Sky of Cloudless Sulphur Revisited :VI PROGRAM DESCRIPTION A light and sound duet utilizing musical resources from my analog recordings combined with my most recent electronic patches and techniques performed spontaneously on my hybrid Buchla 2003/Ableton Live ’instrument’, with video animation by Lillevan. -

Issue 197.Pmd

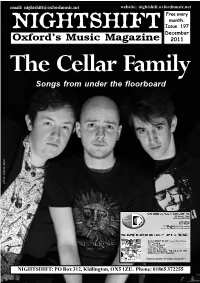

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 197 December Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 The Cellar Family Songs from under the floorboard photo: Johnny Moto NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net taken control of the building three years ago after Solarview, the company that refurbished it after years of neglect, went into liquidation. Trouble at a couple of club nights in the past had earned The Regal a bad reputation in certain sections of the press, but more recently the building looked like it was set to fulfil its potential as the biggest dedicated live music venue in Oxford. SECRET RIVALS release a new single next month. ‘Once More M83 have added a date at the O2 Academy on Tuesday 24th January With Heart’ b/w ‘I Know to their UK tour. The band, centred around French musician and Something’ is released on It’s All producer Anthony Gonzalez, recently followed up their acclaimed JONQUIL return to town for a Happening Records on January 2008 album `Saturdays = Youth’ with new album, `Hurry Up, We’re special Blessing Force-themed 16th. Visit www.secretrivals.com Dreaming. Tickets, priced £12.50, are on sale now from the venue box show at the O2 Academy on for more news on the band. office. Saturday 17th December. They are THE HORRORS, meanwhile, have re-arranged their Academy joined for the night by Pet Moon, THE ORIGINAL RABBIT FOOT show for Thursday 19th January after their original date in October Sisterland and Motherhood as well SPASM BAND play a fundraising was postponed when singer Faris Badwan lost his voice. -

Muc 4313/5315

MUC 4313/5315 Reading Notes: Chadabe - Electric Sound Sample Exams Moog Patch Sheet Project Critique Form Listening List Truax - Letter To A 25-Year Old Electroacoustic Composer Fall 2003 Table of Contents Chadabe - Electric Sound Chapter Page 1 1 2 3 3 7 4 9 5 10 6 14 7 18 8 21 9 24 10 27 11 29 12 33 Appendex 1 – Terms and Abbreviations 35 Appendex 2 – Backus: Fundamental Physical Quantities 36 Sample Exams Exam Page Quiz 1 37 Quiz 2 40 Mid-Term 43 Quiz 3 47 Quiz 4 50 Final 53 Moog Patch Sheet 59 Project Critique Form 60 Listening List 61 Truax - Letter to a 25-Year Old Electroacoustic Composer 62 i Chapter 1, The Early Instruments What we want is an instrument that will give us a continuous sound at any pitch. The composer and the electrician will have to labor together to get it. (Edgard Varèse, 1922) History of Music Technology 27th cent. B.C. - Chinese scales 6th cent. B.C. - Pythagoras, relationship of pitch intervals to numerical frequency ratios (2:1 = 8ve) 2nd cent. C.E. - Ptolemy, scale-like Ptolemaic sequence 16 cent. C.E. - de Salinas, mean tone temperament 17th cent. C.E. - Schnitger, equal temperament Instruments Archicembalo (Vicentino, 17th cent. C.E.) 31 tones/8ve Clavecin electrique (La Borde, 18th cent. C.E.) keyboard control of static charged carillon clappers Futurist Movement L’Arte dei Rumori (Russolo, 1913), description of futurist mechanical orchestra Intonarumori, boxes with hand cranked “noises” Gran concerto futuristica, orchestra of 18 members, performance group of futurist “noises” Musical Telegraph (Gray, 1874) Singing Arc (Duddell, 1899) Thaddeus Cahill Art of and Apparatus for Generating and Distributing Music Electronically (1897) Telharmonium (1898) New York Cahill Telharmonic Company declared bankruptcy (1914) Electrical Means for Producing Musical Notes (De Forest, 1915), using an audion as oscillator, more cost effective Leon Theremin Aetherphone (1920) a.k.a. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Subotnick-Lillevan 2015Edit.2016

Jan. 28, 2016 Washington, DC American University: Song and Dance Feb. 4, 2016 Brooklyn, NY Interpretations at Roulette: Song and Dance April 21, 2016 Copenhagen Jazzhouse: Song and Dance April 23, 2016 Malma, Sweden CTM Festival: Song and Dance May 21, 2016 Durham, NC Moogfest: Song and Dance May 27, 2016 Detroit Trip Metal Fest: Song and Dance Sept. 27, 2016 Brooklyn, NY After 9 Evenings, Issue Project Room: Song and Dance Nov. 1, 2016 London St. John Sessions: Song and Dance Nov. 4, 2016 Berlin Ableton Loop: Song and Dance Dec 27-29, 2016 Israel Colloquium & Performances Feb. 15, 2017 Philadelphia Annenberg Center (w/Lillevan) April 22, 2017 San Francisco Buchla Memorial Festival July 20-22, 2017 NYC Lincoln Center: Crowds and Power Morton Subotnick 2015 Other Events photo credit: Adam Kissick for RECORDINGS WERGO released in June 2015 After the Butterfly The Wild Beasts http://www.schott-music.com/news/archive/show,11777.html?newsCategoryId=19 Upcoming re-releases from vinyl on WERGO Fall 2015: Axolotl, Joel Krosnick, cello A Fluttering of Wings with the Juilliard Sting Quartet Ascent into Air from Double life of Amphibians The Last Dream of the Beat for soprano, Two Celli and Ghost electronics; Featuring Joan La Barbara, soprano Upcoming Mode Records: Complete Piano Music of Morton Subotnick The Other Piano, Liquid Strata, Falling Leaves and Three Piano Preludes. Featuring SooJin Anjou, pianist Release of a K-6 online music curriculum: Morton Subotnicks Music Academy https://musicfirst.com/msma 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM INFO Pg 4 CONCERT LISTING AND BIOS Pg 5 CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pg 6 PRESS PHOTOS Pg 8 AUDIO AND VIDEO LINKS Pg 13 PRESS QUOTES Pg 15 TECH RIDER Pg 19 3 PROGRAM INFO Song and Dance PROGRAM DESCRIPTION A light and sound duet utilizing musical resources from my analog recordings combined with my most recent electronic patches and techniques performed spontaneously on my hybrid Buchla 200e/Ableton Live ’instrument’, with live video animation by Lillevan. -

Section I - Overview

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Masterworks Subject: Terry Riley Discipline: Music SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 SECTION II – PROFILE & CONTEXT..................................................................................................3 ARTIST PROFILE CONTEXT: THE BIG PICTURE.............................................................................................................4 SECTION III – RESOURCES .................................................................................................................6 TEXTS & PERIODICALS AUDIO RECORDINGS WEB SITES VIDEOS SECTION IV – BAY AREA FIELD TRIPS..............................................................................................9 SECTION III – VOCABULARY.......................................................................................................... 10 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 12 Composer Terry Riley reflects on a long, successful career. Still image from SPARK story June 2005. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES Masterworks Individual and group research Individual and group exercises SUBJECT Written research materials Terry Riley Group oral discussion, review and analysis GRADE RANGES K-12, Post-Secondary EQUIPMENT NEEDED TV & VCR with SPARK story “Masterworks,” about CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS Terry Riley and Kronos Quartet Music -

October 1996 There Is No Greater Gift Than to ~

- THE OTHER SIDE VOLUME XXVII OCTOBER.1996 Editor-in-Chief POLITICS S EASON: 0 Shanti Webley Tire political minds of Pit=er rise to f7Tllrftlmv'fliQ Executive Editor: hy justin Anderson, Ed Martini III Albert Aaron Rhodes - ·- ·- ·- ·- ·- ·- ·- ·- ·- --A - -- ·- ·- -·-·- ·- ·- ·- ·-·-·- ·- ·- ·- · WITHOUT A Box'S MISSION Assistant Editors: Putting the "Imp" back in Imprav: Tile group sets out again to reclaim Bill Pluecker their namesake. by jonathan Stokes mfd Aaron Rhodes Angelica Diehn AbbieTew l'liisiArio; · e:i·EViAND . !s-oNFii£ · - · - · - · - · - · - · - · - · - · - · - · - · - · - - - · - - ~ Music Editor: Todd Berry ::si~:= ~~~~-~~~~n~J:.::d~ ~.:~ ~~·-~~~l~nd Mall Rmnirez ~ ' Photographers: Aaron Rhodes GUATEMALA, UP CLOSE AND PERso AL Trillium Sellers Her visions tuzd ~ to. Centml by La Ia Welbom Artists: Liz Biala Tracv Johnson Do-ugWein Thomas Weitz Registered Voters: Justin Anderson Ben Ball Adam Block There are 't ry few reY1ardS J Jose Calderon But there is one reward tl\~t money cannot buy 53.'11 J. Farrar And that no gift in the •orld can ~urpass - Suzanne Foster The gift of your eyes, Tou;r heart, and }'miT mind. Ed Martini ill Zach Pall The moment when your eyes open wide and I can see Matthew Ramirez That you can see Michael A. Rippins The plight of the farmworkers in the fields. r-..fichell Silas The tired arms of the janitor scrubbing the floors in the college halls, Fiona Spring The power relations that create a chasm between Jonathan Stokes Domestication and Liberation -- Rebecca Uchill There is no greater gift -

The Great Practice Master

The Great Practice Whit Griffin 1 The Great Practice Whit Griffin Table Of Contents The Great Practice 3 The Poetics Of Reincarnation 166 A Selected / Suggested Bibliography 182 Acknowledgments 187 2 The Great Practice Whit Griffin The ferocious alligator pisses the tobacco plant. The crying baboons who piss each hour during the equinoxes. Urinating on cereal grains to test for pregnancy. The birth of the divine child, whether he bears the name Horus, Osiris, Helios, Dionysus, or Aeon, was celebrated in the Koreion in Alexandria, in the temple dedicated to Kore, on the day of the winter solstice, when the new divine light is born. The Great Central Sun of Sacred Power. I am perception and Knowledge, uttering a Voice by means of Thought. I am the real Voice. The voice of the sun. The ring of deliverance. The silver apples of wisdom. A wisdom of loving participation. The tortoise stands in opposition to the sun. In the mythology of the oldest known Semitic-Babylonian calendar, the moon signifies life; the sun signifies death. 3 The Great Practice Whit Griffin Some say poets invented the gods, the Trojan War was directed by hallucinations. Was the Israelite exodus from Egypt contemporaneous with the Trojan War? * The lotus blossom of psychic flowering. Energy with the quality of mind. The blond moon. The soul is hundreds of thousands of times finer and more powerful than intelligence. A stream of wind is blowing through the tube of the sun. As the Gorgon is the night sun. As the moon is the night snake that walks in the water. -

A History of Electronic Music Pioneers David Dunn

A HISTORY OF ELECTRONIC MUSIC PIONEERS DAVID DUNN D a v i d D u n n “When intellectual formulations are treated simply renewal in the electronic reconstruction of archaic by relegating them to the past and permitting the perception. simple passage of time to substitute for development, It is specifically a concern for the expansion of the suspicion is justified that such formulations have human perception through a technological strate- not really been mastered, but rather they are being gem that links those tumultuous years of aesthetic suppressed.” and technical experimentation with the 20th cen- —Theodor W. Adorno tury history of modernist exploration of electronic potentials, primarily exemplified by the lineage of “It is the historical necessity, if there is a historical artistic research initiated by electronic sound and necessity in history, that a new decade of electronic music experimentation beginning as far back as television should follow to the past decade of elec- 1906 with the invention of the Telharmonium. This tronic music.” essay traces some of that early history and its —Nam June Paik (1965) implications for our current historical predicament. The other essential argument put forth here is that a more recent period of video experimentation, I N T R O D U C T I O N : beginning in the 1960's, is only one of the later chapters in a history of failed utopianism that Historical facts reinforce the obvious realization dominates the artistic exploration and use of tech- that the major cultural impetus which spawned nology throughout the 20th century. video image experimentation was the American The following pages present an historical context Sixties. -

REDCAT Fall 2013 Press Release

REDCAT Fall 2013 Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 16, 2013 Media Contact: Kelly Hargraves 213-237-2873 [email protected] REDCAT ANNOUNCES ITS TENTH ANNIVERSARY SEASON The Radar L.A. International Festival of Contemporary Theater Launches the Fall 2013 Season of Performances, Film, and Literary Series Featuring: Cynthia Hopkins, Gregory Maqomba, Faifai, Tiger Lillies, Charlie Haden, Angel City Jazz Festival, Now Hear Ensemble, Morton Subotnick, Reinier van Houdt, Nicolas Rey, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Jodie Mack, Bruce Baillie (Los Angeles, CA) – REDCAT, CalArts' downtown center for contemporary arts, under the direction of Mark Murphy, announces its Tenth Anniversary Season, opening in September with the second Radar L.A. International Festival of Contemporary Theater, a one-week event with over 100 performances by 18 companies from Latin America, the Pacific Rim and Los Angeles highlighting the vibrancy of new theater works at historic downtown theaters and venues throughout Los Angeles, produced in association with Center Theatre Group and a consortium of local and national partners. The Gallery at REDCAT launches a new season under the direction of new Curator Ruth Estevez, hosting a series of inspiring international visual artists who are creating new work especially for the gallery. September 21st marks the start of the new installation, Different Kinds of Water Pouring Into a Swimming Pool by Andrés Jaque and his influential Office for Political Innovation, based in Madrid. REDCAT Executive Director Mark Murphy says, “The fall program offers you a range of experiences that exemplify the unique role and contributions of REDCAT and CalArts to the vibrancy of the region’s cultural ecology.” REDCAT opened as CalArts’ downtown center for contemporary arts at the inception of the Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003.