Typological Overview of the Languages of Central and Southern Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

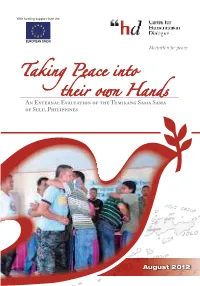

Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands

Taking Peace into An External Evaluation of the Tumikang Sama Sama of Sulu, Philippinestheir own Hands August 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) would like to thank the author of this report, Marides Gardiola, for spending time in Sulu with our local partners and helping us capture the hidden narratives of their triumphs and challenges at mediating clan confl icts. The HD Centre would also like to thank those who have contributed to this evaluation during the focused group discussions and interviews in Zamboanga and Sulu. Our gratitude also goes to Mary Louise Castillo who edited the report, Merlie B. Mendoza for interviewing and writing the profi le of the 5 women mediators featured here, and most especially to the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines, headed by His Excellency Ambassador Guy Ledoux, for believing in the power of local suluanons in resolving their own confl icts. Lastly, our admiration goes to the Tausugs for believing in the transformative power of dialogue. DISCLAIMER This publication is based on the independent evaluation commissioned by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue with funding support from the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines. The claims and assertions in the report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the HD Centre nor of the Eurpean Union. COVER “Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands” expresses how people in the midst of confl ict have taken it upon themselves to transform their situation and usher in relative peace. The cover photo captures the culmination of the mediation process facilitated by the Tumikang Sama Sama along with its partners from the Provincial Government, the Municipal Governments of Panglima Estino and Kalinggalan Caluang, the police and the Marines. -

Domain Dan Bahasa Pilihan Tiga Generasi Etnik Bajau Sama Kota Belud

96 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), Volume 5, Issue 7, (page 96 - 107), 2020 Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH) Volume5, Issue 7, July 2020 e-ISSN : 2504-8562 Journal home page: www.msocialsciences.com Domain dan Bahasa Pilihan Tiga Generasi Etnik Bajau Sama Kota Belud Berawati Renddan1, Adi Yasran Abdul Aziz1, Hasnah Mohamad1, Sharil Nizam Sha'ri1 1Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) Correspondence: Berawati Renddan ([email protected]) ABstrak ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Etnik Bajau Sama merupakan etnik kedua terbesar di negeri Sabah. Kawasan petempatan utama etnik Bajau Sama di Sabah terletak di Kota Belud di Pantai Barat. Sebagai masyarakat yang dwibahasa, pilihan penggunaan bahasa masyarakat yang beragama Islam ini adalah berbeza-beza mengikut generasi dan domain yang berkemungkinan tidak berpihak kepada bahasa ibunda. Teori Analisis Domain (Fishman) diterapkan bagi mengkaji pilihan bahasa dalam domain khusus oleh peserta kajian dari Kampung Taun Gusi, Kota Belud, Sabah. Kaedah tinjauan dengan soal selidik digunakan untuk mendapatkan maklumat daripada generasi pertama (GI), kedua (GII) dan ketiga (GIII). Nilai min bagi setiap kumpulan dlam domain kekeluargaan menunjukkan bahawa GI dan GII Lebih banyak menggunakan bahasa Bajau Sama manakala GIII lebih cenderung kepada bahasa Melayu. Dalam domain kejiranan, GI memilih bahasa Bajau Sama namun GII dan GIII masing-masing memilih BM. Walau bagaimanapun, dalam domain pendidikan, keagamaan, perkhidmatan dan jual-beli, semua generasi memilih bahasa Melayu. Penemuan yang paling penting ialah generasi muda (GIII) kini sudah beralih kepada bahasa Melayu dalam domain kekeluargaan dan domain awam. Generasi ini bertindak sebagai pemangkin peralihan bahasa yang mendatangkan ancaman kepada daya hidup bahasa Bajau Sama, khususnya dalam domain tidak formal seperti kekeluargaan dan kejiranan. -

Biogeography of Mammals in SE Asia: Estimates of Rates of Colonization, Extinction and Speciation

Biological Journal oflhe Linnean Sociely (1986), 28, 127-165. With 8 figures Biogeography of mammals in SE Asia: estimates of rates of colonization, extinction and speciation LAWRENCE R. HEANEY Museum of <oology and Division of Biological Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, U.S.A. Accepted for publication I4 February 1986 Four categories of islands in SE Asia may be identified on the basis of their histories of landbridge connections. Those islands on the shallow, continental Sunda Shelf were joined to the Asian mainland by a broad landbridge during the late Pleistocene; other islands were connected to the Sunda Shelf by a middle Pleistocene landbridge; some were parts of larger oceanic islands; and others remained as isolated oceanic islands. The limits of late Pleistocene islands, defined by the 120 ni bathymetric line, are highly concordant with the limits of faunal regions. Faunal variation among non-volant mammals is high between faunal regions and low within the faunal regions; endcmism of faunal regions characteristically exceeds 70%. Small and geologically young oceanic islands are depauperate; larger and older islands are more species-rich. The number of endemic species is correlated with island area; however, continental shelf islands less than 125000 km2 do not have endemic species, whereas isolated oceanic islands as small as 47 km2 often have endemic species. Geologirally old oceanic islands have many endemic species, whereas young oceanic islands have few endemic species. Colonization across sea channels that were 5-25 km wide during the Pleistocene has been low, with a rate of about 1-2/500000 years. -

Re-Evaluating the Position of Iraya Among Philippine Languages

International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics 13 Academia Sinica, Taipei July 18-23, 2015 Re‐evaluating the position of Iraya among Philippine languages Lawrence A. Reid University of Hawai‘i A L R Presentation Plan • Introduction • About the Iraya language • Position of the Northern Mindoro languages • Contact diffusion into Iraya • Conclusion A L R Mindoro A L R Mindoro A L R Introduction (1) • Iraya is one of the more than 150 Malayo‐Polynesian languages spoken in the Philippines. • It is spoken by the older generation of some 5000 on the island of Mindoro, the 7th largest island in the Philippines. • There are at least 7 languages spoken on the island, of which Iraya is the most northerly and is adjacent to the Batangas area of northern Luzon, where Tagalog is the main language. A L R Introduction (2) • Iraya is distinctly different in a number of features from the other languages of Mindoro, and of the Philippines. • These features include different pronominal forms and functions, several changes in the structure of noun phrases, changes in the patterns of verb structures, changes in word order, and other sentential features, not commonly found in other Philippine languages. A L R Introduction (3) • The question being asked is to what extent these features are retentions, the result of innovations unique to Iraya, or are developments that are the result of contact diffusion. • One factor that needs to be considered: Iraya people have phenotypical features that distinguish them from lowland Philippine peoples, primarily in that they typically have wavy to curly hair, a feature found to a more pronounced degree in Negrito populations of the Philippines, suggesting that these were also a Negrito group that has been heavily influenced by in‐ migration of non‐Negrito peoples. -

Reactions to Blust's ``The Resurrection of Proto-Philippines''

1 Reactions to Blust’s “The Resurrection 2 of Proto-Philippines” 3 R. David Zorc 4 LANGUAGE RESEARCH CENTER AND DUNWOODY PRESS, 5 HYATTSVILLE, MD 6 Blust has secured the position of PPH by raising the number of country-wide 7 innovations to at least 600 etymologies (out of the 1286 proposed). Unlike 8 PMP or PAN, at the phonological level, accent contrasts must be a significant 9 innovation for PPH (although not explicitly stated by Blust, nine minimal pairs 10 are well-established within his survey). An initial *y- and a clear-cut contrast 11 between glottal stop (*ʔ) as opposed to *q can also be reconstructed for PPH. 12 Axis-relationships (areal contact phenomena) have arisen which blur genetic 13 boundaries, but not to any great extent; discreet macro- and microgroups 14 can be substantiated throughout the Philippines, all descended from one 15 proto-language. 16 1. OVERVIEW. Despite the several comments or corrections I have below, I 17 consider Blust’s paper a major contribution to the field. Of the 1286 etymologies 18 presented in appendices 1 and 2,1 well over half (600 or more, see section 6) 19 should stand the test of time. Given that the Philippines was an early landing site 20 for Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP), there were at least 800 years to develop 21 innovations and/or replacements within the archipelago that somehow were not 22 exported. Then, after the dispersal of the Malayo-Polynesian (MP) languages, 23 there were another 2,000 or more years for inter-island interactions. Thus, 24 Idoconcede(videRoss 2005) that there may have been AXIS relationships (areas 25 of heavy contact that transcend historical subgroupings), which I noted were 26 responsible for some replacements that do not correspond with any subgroup 27 (North-Bisayan axis *bakál ‘buy’ replacing PAN *belíh in West Bisayan, Asi, 28 Romblon, Masbate, Hanunoo, and Bikol [ZDS2]; East-Mindanao axis *sidan 29 ‘they’ replacing PMP *sida in Mansakan, Kamayo, Mamanwa, Subanon, Danao, 30 and Binukid Manobo) [ZDS]. -

Axis Relationships in the Philippines – When Traditional Subgrouping Falls Short1 R. David Zorc <[email protected]> AB

Axis Relationships in the Philippines – When Traditional Subgrouping Falls Short1 R. David Zorc <[email protected]> ABSTRACT Most scholars seem to agree that the Malayo-Polynesian expansion left Taiwan around 3,000 BCE and virtually raced south through the Philippines in less than one millenium. From southern Mindanao migrations went westward through Borneo and on to Indonesia, Malaysia, and upwards into the Asian continent (“Malayo”-), and some others went south through Sulawesi also going eastward across the Pacific (-“Polynesian”)2. If this is the case, the Philippine languages are the “left behinds” allowing at least two more millennia for multiple interlanguage contacts within the archipelago. After two proposed major extinctions: archipelago-wide and the Greater Central Philippines (Blust 2019), inter-island associations followed the ebb and flow of dominance, expansion, resettlement, and trade. Little wonder then that “unique” lexemes found on Palawan can appear on Mindoro or Panay; developments throughout the east (Mindanao, the Visayas, and southern Luzon) can appear in Central Luzon, and an unidentified language with the shift of Philippine *R > y had some influence on Palawan and Panay. As early as 1972, while writing up my dissertation (Zorc 1975, then 1977), I found INNOVATIONS that did not belong to any specific subgroup, but had crossed linguistic boundaries to form an “axis” [my term, but related to German “SPRACHBUND”, “NETWORK” (Milroy 1985), “LINKAGE” 3 (Ross 1988. Pawley & Ross 1995)]. Normally, INNOVATIONS should be indicative of subgrouping. However, they can arise in an environment where different language communities develop close trade or societal ties. The word bakál ‘buy’ replaces PAN *bəlih and *mayád ‘good’ replaces PMP *pia in an upper loop from the Western Visayas, through Ilonggo/Hiligaynon, Masbatenyo, Central Sorsoganon, and 1 I am deeply indebted to April Almarines, Drs. -

892-3809-1-PB.Pdf

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines Origins of the Philippine Languages Cecilio Lopez Philippine Studies vol. 15, no. 1 (1967): 130–166 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Origins- of the Philippine Languages CEClLlO LOPEZ 1. Introduction. In the Philippines there are about 70 languages and in Malayo-Polynesia about 500. To say some- thing about unity and diversity among these many languages and about our evidence for their Malayo-Polynesian source is not an easy task, particularly when it must be done briefly and for readers without the requisite linguistic sophistication. For the purposes of this paper, therefore, the best I can do is to explain some representative phenomena, making the presenta- tion as simple as I possibly can. In determining similarities and diversitiea between lan- guages, comparison based on any one of four levels may be used: phonology, morphology, syntax, or vocabulary. The ap- proach using all the four levels is undoubtedly the mast re- liable, particularly if it fulfills the following conditions: exhaus- tiveness of coverage, simplicity of exposition, and elegance of form. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Morphophonology of Magahi

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 SJIF (2019): 7.583 Morphophonology of Magahi Saloni Priya Jawaharlal Nehru University, SLL & CS, New Delhi, India Salonipriya17[at]gmail.com Abstract: Every languages has different types of word formation processes and each and every segment of morphology has a sound. The following paper is concerned with the sound changes or phonemic changes that occur during the word formation process in Magahi. Magahi is an Indo- Aryan Language spoken in eastern parts of Bihar and also in some parts of Jharkhand and West Bengal. The term Morphophonology refers to the interaction of word formation with the sound systems of a language. The paper finds out the phonetic rules interacting with the morphology of lexicons of Magahi. The observations shows that he most frequent morphophonological process are Sandhi, assimilation, Metathesis and Epenthesis. Whereas, the process of Dissimilation, Lenition and Fortition are very Uncommon in nature. Keywords: Morphology, Phonology, Sound Changes, Word formation process, Magahi, Words, Vowels, Consonants 1. Introduction 3.1 The Sources of Magahi Glossary Morphophonology refers to the interaction between Magahi has three kind of vocabulary sources; morphological and phonological or its phonetic processes. i) In the first category, it has those lexemes which has The aim of this paper is to give a detailed account on the been processed or influenced by Sanskrit, Prakrit, sound changes that take place in morphemes, when they Apbhransh, ect. Like, combine to form new words in the language. धमम> ध륍म> धरम, स셍म> सꥍ셍> सााँ셍 ii) In the second category, it has those words which are 2. -

Computational Linguistics Research on Philippine Languages

Computational Linguistics Research on Philippine Languages Rachel Edita O. ROXAS Allan BORRA Software Technology Department Software Technology Department De La Salle University De La Salle University 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines [email protected] [email protected] languages spoken in Southern Philippines. But Abstract as of yet, extensive research has already been done on theoretical linguistics and little is This is a paper that describes computational known for computational linguistics. In fact, the linguistic activities on Philippines computational linguistics researches on languages. The Philippines is an archipelago Philippine languages are mainly focused on 1 with vast numbers of islands and numerous Tagalog. There are also notable work done on languages. The tasks of understanding, Ilocano. representing and implementing these Kroeger (1993) showed the importance of the languages require enormous work. An grammatical relations in Tagalog, such as extensive amount of work has been done on subject and object relations, and the understanding at least some of the major insufficiency of a surface phrase structure Philippine languages, but little has been paradigm to represent these relations. This issue done on the computational aspect. Majority was further discussed in the LFG98, which is on of the latter has been on the purpose of the problem of voice and grammatical functions machine translation. in Western Austronesian Languages. Musgrave (1998) introduced the problem certain verbs in 1 Philippine Languages these languages that can head more than one transitive clause type. Foley (1998) and Kroeger Within the 7,200 islands of the Philippine (1998), in particular, discussed about long archipelago, there are about one hundred and debated issues such as nouns in Tagalog that can one (101) languages that are spoken. -

Modeling the Linguistic Situation in the Philippines

SENRI ETHNOLOGICAL STUDIES ●: 1–15 ©2018 Let’s Talk about Trees: Genetic Relationships of Languages and Their Phylogenic Representation Edited by KIKUSAWA Ritsuko and Lawrence A. REID Modeling the Linguistic Situation in the Philippines Lawrence A. Reid University of Hawai‘i National Museum of the Philippines Abstract This paper explores various problems in modeling the Philippine linguistic situation. Simple cladistic models are valuable in modeling proposed genetic relationships based on the results of the comparative-historical method, but are problematic when dealing with the languages of Negrito groups that adopted Austronesian languages. They are also problematic in dealing with networking as the result of dialect chaining, and widespread lexical borrowing from non-Austronesian languages, each of which creates special problems in modeling the Philippine linguistic situation. 1. Introduction In order to understand the problems involved with modeling the linguistic situation in the Philippines, it is necessary to introduce some facts about the country. The Philippines has a population of over 90,000,000 spread over 7000 islands. The major islands have a wide variety of geographical features, with high mountain ranges, wide river plains and valleys. Ethnologue (Simons and Fennig 2017) lists 175 indigenous Philippine languages that are spoken by two phylogenetically distinct groups, the so-called “Southern Mongoloid” and the “Negritos”. All Philippine languages belong to the Austronesian language family. Despite proposals to the contrary (e.g., Donohue and Denham 2010: 231; 248), there is no linguistic evidence, for prehistoric contact between either of the two phylogenetically distinct groups in the Philippines and any other known linguistic phylum, such as Austro- Asiatic or any other island or mainland non-Austronesian Southeast Asian group.