Enculturation of Kledi Dayak Kebahan Penyelopat (Inheritance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

Bang on a Can Announces Onebeat Marathon #2 Live Online! Sunday, May 2, 2021 from 12PM - 4PM EDT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press contact: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists 646.536.7864 x2, [email protected] Bang on a Can Announces OneBeat Marathon #2 Live Online! Sunday, May 2, 2021 from 12PM - 4PM EDT A Global Music Celebration curated and hosted by Found Sound Nation. Four Hours of LIVE Music at live.bangonacan.org Note: An embed code for the OneBeat Marathon livestream will be available to press upon request, to allow for hosting the livestream on your site. The OneBeat Virtual Marathon is back! OneBeat, a singular global music exchange led by our Found Sound Nation team, employs collaborative original music as a potent new form of cultural diplomacy. We are thrilled to present this second virtual event, showcasing creative musicians who come together to make music, not war. The OneBeat Marathon brings together disparate musical communities, offering virtuosic creators a space to share their work. These spectacular musicians join us from across the globe, from a wide range of musical traditions. They illuminate our world, open our ears, and break through the barriers that keep us apart. - Julia Wolfe, Bang on a Can co-founder and co-artistic director Brooklyn, NY — Bang on a Can is excited to present the second OneBeat Marathon – Live Online – on Sunday, May 2, 2021 from 12PM - 4PM ET, curated by Found Sound Nation, its social practice and global collaboration wing. Over four hours the OneBeat Marathon will share the power of music and tap into the most urgent and essential sounds of our time. From the Kyrgyz three-stringed komuz played on the high steppe, to the tranceful marimba de chonta of Colombia's pacific shore, to the Algerian Amazigh highlands and to the trippy organic beats of Bombay’s underground scene – OneBeat finds a unifying possibility of sound that ties us all together. -

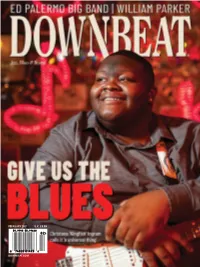

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Squeezeboxnew Directions in Music

NEW DIRECTIONS IN MUSIC SQUEEZEBOXNEW DIRECTIONS IN MUSIC NEW DIRECTIONS IN MUSIC ARTISTIC DIRECTOR’S WELCOME It was the accordion in Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera that hooked me on this chameleon of an instrument. Its very sound conjures up such an aching nostalgia—bittersweet and decadent—that one could feel and smell the Berlin cabarets. It simply gets under your skin. From giddy hysteria to the depths of depression, the accordion family plumbs the full spectrum of human emotion. An instrument that is at home on the street corner as well as in the concert hall, it occupies a unique place in cultures around the globe. Two extraordinary Canadian pioneers, Joseph Macerollo and Joseph Petric, lifted the accordion from novelty status to full-fledged concert instrument, contributing to the creation and performance of new works on a monumental scale. We are delighted to have Joseph Macerollo and his protégé Michael Bridge with us tonight, playing definitive Canadian works by R. Murray Schafer, Alexina Louie, and Marjan Mozetich. The accordion developed in Europe in the 1770s, a descendent of the Chinese sheng, but powered by bellows instead of the breath. Virtuoso performer gamin’s instrument, the Korean saenghwang, is also descended from the sheng. She performs Korean composer Taejong Park and a world premiere by Canadian Anna Pidgorna. The bandoneón, used in popular and religious music, evolved in the 1880s and was brought to Argentina in the 20th century. There, Proud to support SoundMakers. in the streets, it gave birth to the sensational tango and milonga genres, performed tonight in a return visit by legendary Argentinian bandoneón player Héctor del Curto. -

Perfect Pitch and Pitch Standardization

Ian Watson Qualitative Research Methods Department of Sociology Rutgers University Spring 2000 PITCH STANDARDIZATION AND PERFECT PITCH This is really two studies in one. The first is a discussion of the social process of pitch standardization. Nature gives us a smooth continuum of audible sound frequencies on which there are an infinite number of points. But the frequencies of the pitches we actually hear every day cluster around just a few socially conventional points. The first part of this paper tries to explain how and why that happens. It differs from other accounts of pitch standardization (such as Lloyd 1954) in that it tries to show how pitch standardization is just one of many kinds of social coordination, and that all these sorts of coordination share abstract features in common. The second part of this study is a report of six interviews with people who have perfect pitch (also called absolute pitch). Perfect pitch is, among other things, the ability to hear a musical note and then instantly give the name of its pitch. This part of the study is, on the one hand, simply an ethnographic report of the things I learned during six relatively open-ended short interviews with people who have perfect pitch. However, it is my conviction that one cannot come to a full understanding of perfect pitch without a full understanding of pitch standardization. In this sense the first part of the study is simply a preliminary to the second part. Indeed, I propose the thesis that no one would be able to develop perfect pitch if the pitches they hear around them were not distributed categorically, in clusters around a 1 few dozen socially conventional focal points. -

Compendium of Quality Musical Instruments Compiled by Myron Peterson, Urbandale High School Thanks to All Contributors Noted Below

Compendium of Quality Musical Instruments Compiled by Myron Peterson, Urbandale High School Thanks to all contributors noted below. Flute Good Better Best Yamaha 362 Yamaha 462 Pearl 765 Pearl 665 Miyazawa 102 Miyazawa 402 Trevor James Cantabile Miyazawa 202 Piccolo Good Better Best Yamaha YPC32 Yamaha YPC-62 Keefe Any model Yamaha YPC-81, 82 Hammig Any model Emerson Boston Legacy Hammig 650/2 or 3 Merchants: Rieman's Music Uptempo Music West Music, Coralville, IA Woodwind Brasswind Miyazawa Flutes Hammig Piccolos Contributors Margaret Kegel Amy Sams Compendium of Quality Musical Instruments Compiled by Myron Peterson, Urbandale High School Thanks to all contributors noted below. Oboe Good Better Best Fox Renard 300 Fox Renard 330, 330 Protégé Yamaha TOB-831 or 841 Fox 450 Loree Royal Rigoutat Rlec Fossati Howarth Bassoon Good Better Best Fox Renard 222 Fox Renard 220 Merchants: Rieman's Music Uptempo Music Woodwind Brasswind Midwest Musical Importswww.mmimports.com/index.html Contributors Leslie Fleer Jade Fox Cassidy Noring Melanie Spohnheimer Compendium of Quality Musical Instruments Compiled by Myron Peterson, Urbandale High School Thanks to all contributors noted below. Clarinet (B-Flat) Good Better Best Selmer CL211 Buffet Crampon E11 / E13 Buffet Crampon R13 Yamaha 450 Series YCL450N Yamaha CSVR Selmer Paris Signature B16(followed by any combination of Mouthpieces letters / numbers) Better Best Hite Premiere Vandoren M15 or Vandoren M30 Fobes Debut Fobes San Francisco Series (many options here) Vandoren B45 Bass Clarinet (B-flat) -

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques

TC 1-19.30 Percussion Techniques JULY 2018 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard) *TC 1-19.30 (TC 12-43) Training Circular Headquarters No. 1-19.30 Department of the Army Washington, DC, 25 July 2018 Percussion Techniques Contents Page PREFACE................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... xi Chapter 1 BASIC PRINCIPLES OF PERCUSSION PLAYING ................................................. 1-1 History ........................................................................................................................ 1-1 Definitions .................................................................................................................. 1-1 Total Percussionist .................................................................................................... 1-1 General Rules for Percussion Performance .............................................................. 1-2 Chapter 2 SNARE DRUM .......................................................................................................... 2-1 Snare Drum: Physical Composition and Construction ............................................. -

A Contemporary Study of Musical Arts Informed by African Indigenous Knowledge Systems

A CONTEMPORARY STUDY OF MUSICAL ARTS INFORMED BY AFRICAN INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS VOLUME 1 THE ROOT – FOUNDATION Meki Nzewi Ciimda series A contemporary study of musical arts informed by African indigenous knowledge systems Volume 1 Author: Meki Nzewi Music typesetting & illustrations: Odyke Nzewi Reviewer and editor: Christopher Walton Copy editor: Hester Honey Music instrument illustrations: Themba Simabine Proofreading: Chérie M. Vermaak Book design and typesetting: Janco Yspeert ISBN 978-1-920051-62-4 © 2007 Centre for Indigenous Instrumental African Music and Dance (Ciimda) First edition, first impression All rights reserved Production management: Compress www.compress.co.za CONTENTS INTRODUCTION vii MODULE 101: MUSICAL STRUCTURE AND FORM 1 UNIT 1 – REVIEW OF THE ELEMENTS OF MUSIC WRITING 3 TOPIC 1 Symbols for writing music 3 TOPIC 2 Graphic representation of pitches 6 TOPIC 3 Identifying and writing intervals or steps 9 TOPIC 4 Measurement of musical time 16 UNIT 2 – COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE AND FORM OF A MELODY 20 TOPIC 1 Aural and visual features of a melody 20 TOPIC 2 The structure of a melody 21 UNIT 3 – TONE/PITCH ORDER, SCALE SYSTEM AND KEYS 31 TOPIC 1 Tone order 31 TOPIC 2 Scale system 33 TOPIC 3 Keys 34 MODULE 102: FACTORS OF MUSIC APPRECIATION 47 UNIT 1 – FACTORS OF MUSIC-KNOWING AND MUSIC APPRECIATION IN INDIGENOUS AFRICAN CULTURES 49 TOPIC 1 Pulse in African music 49 TOPIC 2 Music and dance relationship in African musical arts 51 TOPIC 3 Cultural sonic preferences 52 TOPIC 4 Cultural rhythm 52 TOPIC 5 Psychical tolerance -

On the Notation and Performance Practice of Extended Just Intonation

On Ben Johnston’s Notation and the Performance Practice of Extended Just Intonation by Marc Sabat 1. Introduction: Two Different E’s Like the metric system, the modern tempered tuning which divides an octave into 12 equal but irrational proportions was a product of a time obsessed with industrial standardization and mass production. In Schönberg’s words: a reduction of natural relations to manageable ones. Its ubiquity in Western musical thinking, epitomized by the pianos which were once present in every home, and transferred by default to fixed-pitch percussion, modern organs and synthesizers, belies its own history as well as everyday musical experience. As a young musician, I studied composition, piano and violin. Early on, I began to learn about musical intervals, the sound of two tones in relation to each other. Without any technical intervention other than a pitch-pipe, I learned to tune my open strings to the notes G - D - A - E by playing two notes at once, listening carefully to eliminate beating between overtone-unisons and seeking a stable, resonant sound-pattern called a “perfect fifth”. At the time, I did not know or need to know that this consonance was the result of a simple mathematical relationship, that the lower string was vibrating twice for every three vibrations of the upper one. However, when I began to learn about placing my fingers on the strings to tune other pitches, the difficulties began. To find the lower E which lies one whole step above the D string, I needed to place my first finger down. -

Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak in Korean Culture1

International Journal of Korean Humanities and Social Sciences Vol. 5/2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/kr.2019.05.05 COEXISTENCE OF CLASSICAL MUSIC AND GUGAK IN KOREAN CULTURE1 SO HYUN PARK, M.A. Conservatory Orchestra Instructor, Korean Bible University (한국성서대학교) Nowon-gu, Seoul, South Korea [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7848-2674 Abstract: Classical music and Korean traditional music ‘Gugak’ in Korean culture try various ways such as creating new music and culture through mutual interchange and fusion for coexistence. The purpose of this study is to investigate the present status of Classical music in Korea that has not been 200 years old during the flowering period and the Japanese colonial period, and the classification of Korean traditional music and musical instruments, and to examine the preservation and succession of traditional Gugak, new 1 This study is based on the presentation of the 6th international Conference on Korean Humanities and Social Sciences, which is a separate session of The 1st Asian Congress, co-organized by Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland and King Sejong Institute from July 13th to 15th in 2018. So Hyun PARK: Coexistence of Classical Music and Gugak… Korean traditional music and fusion Korean traditional music. Finally, it is exemplified that Gugak and Classical music can converge and coexist in various collaborations based on the institutional help of the nation. In conclusion, Classical music and Korean traditional music try to create synergy between them in Korean culture by making various efforts such as new attempts and conservation. Key words: Korean Traditional Music; Gugak; Classical Music; Culture Coexistence. -

The Accordion in Twentieth-Century China A

AN UNTOLD STORY: THE ACCORDION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC AUGUST 2004 By Yin YeeKwan Thesis Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Ricardo D. Trimillos Fred Blake ©Copyright2004 by YinYeeKwan iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My 2002 and 2003 fieldwork in the People's Republic ofChina was funded by The Arts and Sciences Grant from the University ofHawai'i at Manoa (UHM). I am grateful for the generous support. I am also greatly indebted to the accordionists and others I interviewed during this past year in Hong Kong, China, Phoenix City, and Hawai'i: Christie Adams, Chau Puyin, Carmel Lee Kama, 1 Lee Chee Wah, Li Cong, Ren Shirong, Sito Chaohan, Shi Zhenming, Tian Liantao, Wang Biyun, Wang Shusheng, Wang Xiaoping, Yang Wentao, Zhang Gaoping, and Zhang Ziqiang. Their help made it possible to finish this thesis. The directors ofthe accordion factories in China, Wang Tongfang and Wu Rende, also provided significant help. Writing a thesis is not the work ofonly one person. Without the help offriends during the past years, I could not have obtained those materials that were invaluable for writings ofthis thesis. I would like to acknowledge their help here: Chen Linqun, Chen Yingshi, Cheng Wai Tao, Luo Minghui, Wong Chi Chiu, Wang Jianxin, Yang Minkang, and Zhang Zhentao. Two others, Lee Chinghuei and Kaoru provided me with accordion materials from Japan. I am grateful for the guidance and advice ofmy committee members: Professors Frederick Lau, Ricardo D.