Chapter 4 the Territorial Organisation of Gaelic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inniskeen Spatial Plan DRAFT

Inniskeen Village Public Realm Spatial Plan (DRAFT) 12th Fenruary 2021 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Analysis 3. Concept 4. Key Spaces 5. Spatial Plan 6. Costs & Phasing Introduction Inniskeen Public Realm Spatial Plan has been prepared to inform the future development of public realm in and around Inniskeen for both locals and visitors alike. Spatial Plan Context Inniskeen is a small village located in Co.Monaghan, it is a historic settlement rich in archaeology, landscape features and architectural character, which inspired much of Patrick Kavanagh’s early work as a writer. There are two areas of commercial activity, at the road junction at McNello’s Pub which includes a public house, a petrol station, shop, and credit union. The second commercial centre is at the former railway station cluster including Magee’s public house and shop. Community uses dominate the centre of the village including the river walk, pitch and putt course, Community Centre, National School, Church of Ireland, Round Tower, Graveyard, and the Patrick Kavanagh Centre. Residential development occurs within the village centre to the north west and principally to the west of the village. Brief The Project Brief was to deliver a design which enhances the architectural quality of the sensitive streetscape, provides a high-quality concept and incorporates the following principles: • Reinvent the village as a place for people. • Development of pedestrian linkages between the Village, Kavanagh Centre and the Monaghan Way/ Railway Station. • Designation of key urban spaces for enhancement and specifi c urban design proposals. • Realisation of the potential of heritage and cultural assets for both locals and visitors. -

A'railway Or Railways, Tr'araroad Or Trainroads, to Be Called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the Town of Dundalk in the Count

2411 a'railway or railways, tr'araroad or trainroads, to be den and Corrick iti the parish of Kilsherdncy in the* called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the town barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Killnacreena, Cor- of Dundalk in the county .of.Loiith to the town of nacarrew, Drumnaskey, Mullaghboy and Largy in Cavan, in the county of Cavan, and proper works, the parish of Ashfield in the barony of Tullygarvy piers, bridges; tunnels,, stations, wharfs and other aforesaid, Tullawella, Cornabest, Cornacarrew,, conveniences for the passage of coaches, waggons, Drumrane and Drumgallon in the parish of Drung and other, carriages properly adapted thereto, said in the barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Glynchgny railway or railways, tramway or tramways, com- or Carragh, Drumlane, Lisclone, Lisleagh, Lisha- mencing at or near the quay of Dundalk, in the thew, Curfyhone; Raskil and Drumneragh in the parish and town of Dundalk, and terminating at or parish of Laragh and barony of Tullygarvy afore- near the town of Cavan, in the county of Cavan, said, Cloneroy in the parish of Ballyhays in the ba- passing through and into the following townlands, rony of Upper Loughtee, Pottle Drumranghra, parishes, places, T and counties, viz. the town and Shankil, Killagawy, Billis, Strgillagh, Drumcarne,.- townlands of Dundalk, Farrendreg, and Newtoun Killynebba, Armaskerry, Drumalee, Killymooney Balregan, -in the parish of Gastletoun, and barony and Kynypottle in the parishes of Annagilliff and of Upper Dundalk, Lisnawillyin the parish of Dun- Armagh, barony of -

Portfolio of Glaslough

An oasis of calm, where the hse is king GLASLOUGH CO MONAGHAN IRELAND INfORMAtION Q pORtfOLIO xxx ENtENtE fLORAL/E EUROpE 2017 CONtENtS foreword ...........................................................1 Beautiful Glaslough .......................................2 planning & Development ...........................3 Natural Environment ...................................5 Built Environment ..........................................7 Landscape ........................................................9 Green Spaces ..............................................10 planting ...........................................................13 Environmental Education ........................15 Effort & Involvement .................................17 tourism & Leisure .....................................18 Community ....................................................21 The Boathouse at Castle Leslie Estate. fOREwORD elcome to beautiful Glaslough, t is a very special privilege to welcome an oasis of calm tucked away the International Jury of Entente Florale Wbetween counties Monaghan, Ito Co. Monaghan to adjudicate Armagh and Tyrone. We were both thrilled Glaslough as one o@f Ireland’s and honoured to be nominated to representatives in this year’s competition. represent Ireland in this year’s Entente Co. Monaghan may not be one of the Florale competition. We hope to do better known tourist destinations of Ireland justice, and that you enjoy the best Ireland, but we are confident that after of scenery and hospitality during your stay spending a day -

National University of Ireland Maynooth the ANCIENT ORDER

National University of Ireland Maynooth THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN COUNTY MONAGHAN WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PARISH OF AGHABOG FROM 1900 TO 1933 by SEAMUS McPHILLIPS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr. J. Hill July 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement--------------------------------------------------------------------- iv Abbreviations---------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Chapter I The A.O.H. and the U.I.L. 1900 - 0 7 ------------------------------------43 Chapter II Death and destruction as home rule is denied 1908 - 21-------------81 Chapter III The A.O.H. in County Monaghan after partition 1922- 33 -------120 Conclusion-------------------------------------------------------------------------------143 ii FIGURES Figure 1 Lewis’s Map of 1837 showing Aghabog’s location in relation to County Monaghan------------------------------------------ 12 Figure 2 P. J. Duffy’s map of Aghabog parish showing the 68 townlands--------------------------------------------------13 Figure 3 P. J. Duffy’s map of the civil parishes of Clogher showing Aghabog in relation to the surrounding parishes-----------14 TABLES Table 1 Population and houses of Aghabog 1841 to 1911-------------------- 19 Illustrations------------------------------------------------------------------------------152 -

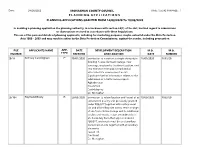

PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED from 14/09/2020 to 18/09/2020

Date: 24/09/2020 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 1:56:42 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 14/09/2020 To 18/09/2020 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION M.O. M.O. NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED AND LOCATION DATE NUMBER 20/34 Anthony Cunningham P 30/01/2020 permission to construct a single storey style 16/09/2020 P855/20 dwelling house, domestic garage, new sewerage, wastewater treatment system, and new entrance onto public road and all associated site development works. Significant further information relates to the submission of a traffic survey report Aghadreenan Broomfield Castleblayney Co. Monaghan 20/104 Raymond Brady R 20/03/2020 permission to retain location and layout of as 18/09/2020 P863/20 constructed poultry unit previously granted under P08/627 together with vertical meal bin and all ancillary site works, retain change of use from nitrate storage unit to additional poultry unit on site, retain amendment's to site boundary from that approved under P08/627, and retain meal bin and ancillary store/shed on site together with all ancillary site works Tassan Td. -

Death Notices and Obituaries Northern Standard 1850-1859

DEATH NOTICE’S AND OBITUARIES IN THE NORTHERN STANDARD 1850 - 1859 Adams, Charles James FarmHill, Clones 17th January 1857 Page.160 Adams, Jane Drumcaw 17th January 1852 Page. 55 Anketell, William Anketell Grove 26th April 1851 Page. 37 Armstrong, John Monaghan 29th March 1851 Page. 33 Barclay, Hugh Diamond, Monaghan 23rd February 1850 Page. 3 Barns, Sarah Ballybay 12th July 1851 Page. 43 Bashford, Margaret Carrickmacross 17th December 1853 Page. 98 Bell, Alexander Billis 26th April 1851 Page. 37 Bellew, Patrick Rev Monaghan 8th February 1851 Page. 29 Bennie, John Farmoyle House 9th April 1853 Page. 86 Birch, Eliza Castleblayney 27th September 1856 Page.153 Blayney, Lady Castleblayney 11th March 1854 Page.107 Bleckley, Mrs Monaghan 16th July 1853 Page.87 Bodely, Robert Drumgrole 4th August 1855 Page.136 Booth,Jane Armstrong Clones 6th March 1858 Page.186 Boyd, Henry Castleblayney 30th December 1854 Page.128 Boyd, James Castleblayney 16th May 1857 Page.166 Boyd, Mary Castleblayney 3rd December 1853 Page. 96 Bradshaw, Jane Eliza Clones 24th September 1853 Page. 91 Breakey, William Ballidian 29th May 1852 Page. 66 Breaky, Isabella Diamond, Monaghan 3rd June 1854 Page.113 Burnell, Eleanor Monaghan 11th January 1851 Page. 25 Campbell, John Crowey 28th August 1858 Page.192 Cargill, Jane Mulladuff 13th March 1852 Page. 60 Cargill, William Glaslough 3rd September 1853 Page. 90 Carroll, Mr Monaghan 28th December 1850 Page. 24 Chambers, David Monaghan 2nd May 1857 Page.165 Charleton, Anne Tully, Emyvale 17th January 1852 Page. 55 Clarke, Alicia Drumreaske, Monaghan 8th June 1850 Page. 12 Clarke, Matthew, Rev. Ballyho Bridge, Clones 13th April 1850 Page. -

File Number Monaghan County Council

DATE : 07/03/2019 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:25:50 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/02/19 TO 15/02/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 19/60 Tiarnan Hand & Rebecca P 11/02/2019 permission for a single storey house, waste water Kenny treatment plant, a new site entrance and associated site works Drumass Inniskeen Co Monaghan 19/61 Norman Francey P 12/02/2019 permission to construct a new free range poultry unit, new litter store, roads underpass, hardened area, vertical meal bins, underground washings, tanks and all ancillary site works Corkish Td Newbliss Co Monaghan 19/62 Damien & Celina Babington P 12/02/2019 permission for a dwelling house, waste water treatment unit, and percolation area, & new entrance onto public road and all associated site works Drumcarrow Carrickmacross Co Monaghan 19/63 Paul & Emma Murphy P 12/02/2019 permission to erect a two storey extension to rear of existing dwelling and all associated site works. Raferagh Shercock Co Monaghan DATE : 07/03/2019 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:25:50 PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/02/19 TO 15/02/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. -

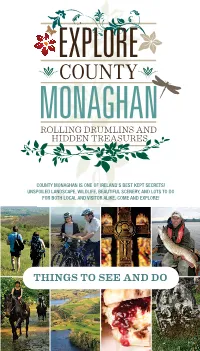

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST. -

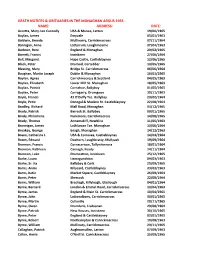

Death Notices & Obituaries in the Monaghan Argus 1963

DEATH NOTICES & OBITUARIES IN THE MONAGHAN ARGUS 1963 - NAME: ADDRESS: DATE: Accetta, Mary nee Connolly USA & Munea, Latton 19/06/1965 Boylan, James Emyvale 05/01/1963 Baldwin, Brenda Mullinarry, Carrickmacross 07/11/1964 Bannigan, Anne Lattycrum, Loughmourne 27/04/1963 Barbour, Roni England & Monaghan 20/02/1965 Barrett, Francis Inniskeen 27/06/1964 Bell, Margaret Hope Castle, Castleblayney 12/06/1965 Black, Peter Drumod, Cortubber 13/05/1965 Blessing, Mary Bridge St. Carrickmacross 06/06/1964 Boughan, Martin Joseph Dublin & Monaghan 16/01/1965 Boylan, Agnes Carrickmacross & Scotland 04/05/1963 Boylan, Elizabeth Lower Mill St. Monaghan 18/05/1963 Boylan, Patrick Cornahoe, Ballybay 01/05/1965 Boylan, Peter Corragarry, Drumgoon 30/11/1963 Boyle, Francis 43 O'Duffy Tce. Ballybay 29/02/1964 Boyle, Petie Donegal & Muckno St. Castleblayney 22/08/1964 Bradley, Richard Mall Road, Monaghan 04/12/1965 Brady, Patrick Barrack St. Ballybay 09/01/1965 Brady, Philomena Nuremore, Carrickmacross 14/08/1965 Brady, Thomas Annamakiff, Newbliss 11/05/1963 Brannigan, James Lathlurcan Tce. Monaghan 13/06/1964 Breakey, George Enagh, Monaghan 14/12/1963 Breen, Catherine J. USA & Corravee, Castleblayney 14/03/1964 Breen, Edward Doohorn, Loughbratty, Mullyash 19/09/1964 Brennan, Francis Cornacarrow, Tullynhinnera 18/01/1964 Brennan, Kathleen Carnagh, Keady 14/11/1964 Brennan, Luke Drumcatton, Inniskeen 25/12/1965 Burke, Laura Lismagunshion 09/03/1963 Burke, Sr. Ita Ballybay & Cork 25/09/1965 Burns, Annie Killycard, Castleblayney 23/02/1963 Burns, Katie Market Square, Castleblayney 26/09/1964 Burns, Peter Shercock 22/08/1964 Burns, William Brackagh, Killyleagh, Glaslough 04/01/1964 Byrne, Bernard London & Emmet Road, Carrickmacross 13/04/1963 Byrne, James England & Main St. -

VA90.1.017 – Helen Drumm T.A Sound Quality

Appeal No. VA90/1/017 AN BINSE LUACHÁLA VALUATION TRIBUNAL AN tACHT LUACHÁLA, 1988 VALUATION ACT, 1988 Helen Drum t/a Sound Quality APPELLANT and Commissioner of Valuation RESPONDENT RE: Shop at Lot No. 12b Townland of Rooskey (Dublin Street), Urban District of Monaghan, Co. Monaghan Quantum - Passing rent, location adjacent to S.C. B E F O R E Henry Abbott Barrister Chairman Brian O'Farrell Valuer Veronica Gates Barrister JUDGMENT OF THE VALUATION TRIBUNAL ISSUED ON THE 22ND DAY OF JANUARY, 1991 By notice of appeal dated the 30th of April, 1990, the appellant appealed against the determination of the Commissioner of Valuation in fixing a rateable valuation of £26.00 on the above described hereditament. The grounds of appeal as set out in the Notice of appeal are "I have the wholly confined use of a small on-street shop premises. I operate a record/tape retail outlet and am two years in business. This is my first venture into business life having been three years umemployed. There is stiff competition here and I am finding it altogether very difficult to manage. This is penal in the 2 extreme and may leave me no choice but to join the many other young people who have already found themselves unable to succeed in todays high cost business world." DESCRIPTION OF PROPERTY: The premises consist of a lock-up 'record shop' with frontage to Dublin Street, Monaghan. It is situated approximately 200 ft from The Diamond. It is held on a three year lease from March 1988. There is a shop floor area of 237 sq.ft. -

Submission Acknowledge on Pig & Poultry Applications

From: Licensing Staff Sent: 20 July 2018 11:34 Subject: Submission Acknowledge on Pig & Poultry applications/reviews Dear Mr Sweetman I acknowledge receipt of your email on 17th July 2018 in relation to a number of licence applications/reviews set out in the table below. DDS BRADY FARMS Carrickboy Farms, Ballyglasson, P0408-02 LIMITED Edgeworthstown, County Longford. P0422-03 Silver Hill Foods Hillcrest, Emyvale, County Monaghan. P0515-02 Laragan Farms Limited Laragan, Elphin, County Roscommon. P0640-02 Mr John Kiernan Tullynaskeagh, Bailieboro, County Cavan. P0790-03 Mr EoinOBrien Annistown, Killleagh, County Cork. P0837-03 F. OHarte Poultry Limited Creevaghy, Clones, County Monaghan. Corlat (Dartree By.), Smithborough, County P0853-02 Mr James Corr Monaghan. P0861-03 Mr Bernard Treanor Doogary, Tydavnet, County Monaghan. P0871-02 Mr Vincent Quinn Cornanagh, Ballybay, County Monaghan. P0878-03 Glenbeg Poultry Limited Glenbeg, Carrickroe, County Monaghan. P0879-02 Mr Leo Treanor Corvoy, Ballybay, County Monaghan. P0880-02 Mr Brian Coleman Longfield, Castleblayney, County Monaghan. P0926-03 Mr Nigel Flynn Tiernahinch Far, Clones, County Monaghan. Tankerstown Pig & Farm Tankerstown, Bansha, Tipperary, County P0965-01 Enterprises Limited Tipperary. Joristown Upper, Killucan, County Westmeath, P0975-02 Clondrisse Pig Farm Limited N91 HK27. P0976-03 Senark Farm Limited Aghnaglough, Stranooden, County Monaghan. P0979-01 Thomas & Trevor Galvin Ballyharrahan, Ring, Co Waterford. P1024-02 Doon Farm Enterprises Limited Doon, Araglin, Kilworth, County Tipperary. Messrs Gerard & Raymond P1029-02 Davagh Otra, Emyvale, County Monaghan. Tierney P1031-02 Kilfilum Limited Nantinan, Milltown, County Kerry. P1032-02 Mile Tree Farms Limited Clashiniska Lower, Clonmel, County Tipperary. P1041-01 Stephen and Carol Brady Clontybunnia, Scotstown, County Monaghan. -

Smythe-Wood Series B

Mainly Ulster families – “B” series – Smythe-Wood Newspaper Index Irish Genealogical Research Society Dr P Smythe-Wood’s Irish Newspaper Index Selected families, mainly from Ulster ‘SERIES B’ The late Dr Patrick Smythe-Wood presented a large collection of card indexes to the IGRS Library, reflecting his various interests, - the Irish in Canada, Ulster families, various professions etc. These include abstracts from various Irish Newspapers, including the Belfast Newsletter, which are printed below. Abstracts are included for all papers up to 1864, but excluding any entries in the Belfast Newsletter prior to 1801, as they are fully available online. Dr Smythe-Wood often found entries in several newspapers for the one event, & these will be shown as one entry below. Entries dealing with RIC Officers, Customs & Excise Officers, Coastguards, Prison Officers, & Irish families in Canada will be dealt with in separate files. In most cases, Dr Smythe-Wood has recorded the exact entry, but in some, marked thus *, the entries were adjusted into a database, so should be treated with more caution. There are further large card indexes of Miscellaneous notes on families which are not at present being digitised, but which often deal with the same families treated below. ACR: Acadian Recorder LON The London Magazine ANC: Anglo-Celt LSL Londonderry Sentinel ARG Armagh Guardian LST Londonderry Standard BAA Ballina Advertiser LUR Lurgan Times BAI Ballina Impartial MAC Mayo Constitution BAU Banner of Ulster NAT The Nation BCC Belfast Commercial Chronicle NCT