Magical Realism in Neil Gaiman's Coraline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghosts – Or the (Nearly) Invisible

9 In this volume, ghost stories are studied in the context of their media, their place in history and geography. From prehistory to this day, we have been haunted by our memories, the past itself, by inklings of the future, by events playing outside our lives, and by ourselves. Hence the lure of ghost stories throughout history 9 Volume and presumably prehistory. Science has been a great destroyer of myth and superstition, but at the same time it has created new black boxes which we are ALPHALPH Approaches to Literary Phantasy filling with our ghostly imagination. In this book, literature from the Middle Ages to Oscar Wilde and Neil Gaiman, children’s stories, folklore and films, ranging from the Antarctic and Russia to Haiti, are covered and show the continuing presence of spectral phenomena. Maria Fleischhack / Elmar Schenkel (eds.) Elmar Schenkel (eds.) · Ghosts – or the (Nearly) Invisible / Ghosts – Maria Fleischhack lectures at Leipzig University with a focus on Victorian and Postmodern fiction and Shakespearean drama; special interest: Sherlock or the (Nearly) Invisible Holmes. Elmar Schenkel teaches English Literature at the University of Leipzig. He has Spectral Phenomena in Literature published on Wells, Conrad and Tolkien and the relations between science and the Media and literature. Maria Fleischhack ISBN 978-3-631-66566-4 Guy Tourlamain - 978-3-0353-9996-7 Downloaded from PubFactory at 09/23/2021 02:26:57PM via free access ALPH 09_266566_Fleischhack_gr_HCA5_Eng PLE.indd 1 28.06.16 KW 26 14:24 9 In this volume, ghost stories are studied in the context of their media, their place in history and geography. -

Coraline by Neil Gaiman

Children's Book and Media Review Volume 33 Issue 2 Article 5 2013 Coraline by Neil Gaiman Jameson Testi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Testi, Jameson (2013) "Coraline by Neil Gaiman," Children's Book and Media Review: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cbmr/vol33/iss2/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Children's Book and Media Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Testi: Coraline by Neil Gaiman Author: Gaiman, Neil Title: Coraline Year of Publication: 2002 Publisher: HarperCollins ISBN: 9780380977789 # of pages: 163 Rating: Excellent Reading/Interest Level: Intermediate Keywords: Supernatural; Parents; Adventure; Novels Review: Coraline Jones always craved an adventure, though she never expected to find one inside her own house. A small door in her flat leads her to a new world with a house identical to her own, though everything is more picturesque. In the new world, she has caring parents, wonderful food, lots of adventures—all things she lacks in her normal life. Coraline visits the new world frequently, but soon discovers the place is full of dark and evil secrets. Her real parents go missing, a strange creature poses as her ‘Other Mother’, and she feels trapped inside a world where she is doomed to die. With her real parent’s lives on the line, Coraline must risk her life to save them and stop the Other Mother from continuing her wicked ways. -

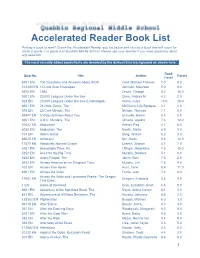

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

BEFORE YOU START Prepare a Group Journal to Help You Record Group Discussions and Responses to the Text As You Work Through the Book

BEFORE YOU START Prepare a group journal to help you record group discussions and responses to the text as you work through the book. These notes refer to the edition illustrated by Chris Riddell but can also be used with Dave McKean’s original illustrations, with some minor adjustments. You could create a glossary of new vocabulary as you read the book – you may want to prepare a format for doing this. As you go through the book, ask the group to pick out words they are unfamiliar with or do not fully understand, such as velvet, muzzle, vermin, raggedy, embroidery, vivid, monstrous, anteroom, shovelled, commercials and rummaged. You could prepare photographs and video sources to bring these words to life and help the pupils use them in context. © Bloomsbury SESSION 1: CHAPTER 1 Focus: Predicting, Close Reading, Thinking Aloud and Summarising Share the front cover with the group. (Do not share the back cover at this point as it reveals some aspects of the plot you may wish to hold back while the children make predictions.) Ask the children to predict what the story could be about. Ask them to justify their responses, drawing out any connections they make to other stories. Record the children’s responses in the journal. Once you have recorded their predictions you can return to these as you read the book, comparing the children’s initial thoughts to how the story actually unfolds. –––––– © Bloomsbury Encourage the children to look in detail at the cover illustration and make connections between this text and other stories they know. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 2-1-2003 SFRA ewN sletter 262 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 262 " (2003). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 78. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. #262 Jan,-Feb, 200J Editor: Christine Mains Manacing Editor: Janice M. Bogstad Nonfiction Reviews: Ed McKnight Fiction Reviews: Philip Snyder The SFRAReview (ISSN 1M ... HIS ISSUE: 1068-395X) is published six times a year by the Science Fiction Research As sociation (SFRA) and distributed to SFRA SFRA Business members. Indi ... idu3.1 iswes are not for sale; however, starting with issue #256, President's Message .2 all issues will be published to SFRA's Minutes of the Executive Meeting website no less than two months after paper publication. For information about Features the SFRA and its benefits, see the de scription at the back of this issue. For a Interview with Greg Bear 6 membership application, contact SFRA Approaches to PerdIdo Street StatIon: Treasurer Dave Mead or get one from I Just Like Monsters 7 the SFRA website: <www.sfra.org>. -

Read Alike List

Read Alike List Juvenile/YA Fiction If you liked…. -The Fault in our Stars—If I Stay by Gayle Forman, Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell, Elsewhere by Gabrielle Zevin, Every Day by David Levithan, Zac and Mia by A.J. Betts, Paper Towns by John Green, Winger by Andrew Smith, And We Stay by Jenny Hubbard, An Abundance of Katherines by John Green, Wintergirls by Laurie Halse Anderson, Anna and the French Kiss by Stephanie Perkins, The Spectacular Now by Tim Tharp, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl by Jesse Andrews, Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple, The Future of Us by Jay Asher & Carolyn Mackler, My Life After Now by Jessica Verdi, The Sky is Everywhere by Jandy Nelson, Twenty Boy Summer by Sarah Ockler, Love and Leftovers by Sarah Tregay, How to Save a Life by Sara Zarr, It’s Kind of a Funny Story by Ned Vizzini, The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky, Looking for Alaska by John Green, Before I Fall by Lauren Oliver, Memoirs of a Teenage Amnesiac by Gabrielle Zevin, 13 Reasons Why by Jay Asher, 13 Little Blue Envelopes by Maureen Johnson, Amy & Roger’s Epic Detour by Morgan Matson, The Beginning of Everything by Robyn Schneider, Me Before You by Jojo Moyes, Ask the Passengers by A.S. King, Love Letters to the Dead by Ava Dellaira -Divergent—Matched by Allyson Condie, Delirium by Lauren Oliver, Uglies by Scott Westerfeld, The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins , The Giver by Lois Lowry, Unwind by Neal Shusterman, The Knife of Never Letting Go by Patrick Ness, Legend by Marie Lu, the Gone series by Michael Grant, Blood Red Road by Moira Young, The Maze Runner by James Dashner, The Selection by Kiera Cass, Article 5 by Kristen Simmons, Witch & Wizard by James Patterson, The Way We Fall by Megan Crewe, Shatter Me by Tahereh Mafi, Enclave by Ann Aguirre, Reboot by Amy Tintera, The Program by Suzanne Young, Taken by Erin Bowman, Birthmarked by Caragh M. -

B.A.Thesis.Pdf

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jitka Marková The Fantastic Worlds as a Representation of the Collective Human Unconscious in the Books by Neil Gaiman Bachelor ’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph. D. 2008 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Jitka Marková 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank Mr. Stephen Paul Hardy, PhD. for supervising my thesis and for his advice during the process of writing, and Mgr. Tomáš Hanzálek and Bc. Michaela Sochorová for advice concerning the administrative affairs. 3 TableofContents Introduction………………………………………………….. 5 1. Theoretical background …………………………….…… 9 1.1. Fantasy as a Genre ……………………………. 9 1.2. Jung and the Collective Unconscious…………… 14 1.3. Functions of Dramatis Personae…………………. 17 2. Neverwhere : Encounter of the Old and Modern World...... 20 3. Stardust : Conscious and Unconscious in Harmony………. 34 4. Coraline : The ‘Other’ World………………………………. 40 Conclusion……………………………………………………. 46 Works Cited …………………………………………………. 50 4 Introduction Thefollowingworkdealswiththerelationships betweenmainstreamsocietyand fantasticworldsinbooks byNeilGaimanfromthe pointofviewofanalytical psychology.Themaingoalofthethesisis toprovethatfantasticworldsdescribedin these books maybeinterpretedasthecollectiveunconscious of peoplelivingwithinthe mainstream society.Itwill bearguedthat the journeyofthemaincharacter,whichplays -

Folklore and Mythology in Neil Gaiman's American Gods

FOLKLORE AND MYTHOLOGY IN NEIL GAIMAN'S AMERICAN GODS by SEAN EDWARD DIXON A THESIS Presented to the Folklore Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Sean Edward Dixon Title: Folklore and Mythology in Neil Gaiman's American Gods This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Folklore Program by: Daniel Wojcik Chairperson John Baumann Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Sean Edward Dixon iii THESIS ABSTRACT Sean Edward Dixon Master of Arts Folklore Program June 2017 Title: Folklore and Mythology in Neil Gaiman's American Gods This thesis provides a critical analysis of the use of folklore and mythology that exists in Neil Gaiman's award-winning novel, American Gods. I focus on the ways in which American Gods is situated within an intertextual corpus of mythological and mythopoeic writing. In particular, this study analyses Gaiman’s writing by drawing upon Mircea Eliade’s ideas about mythology and Northrop Frye’s archetypal criticism to discuss the emergence of secular myth through fantasy fiction. iv CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Sean Edward Dixon GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, Eugene American University, Washington DC DEGREES AWARDED: Master of Arts, -

September 2020

NEW E-BOOKS SEPTEMBER 2020 Call Title Number Author Audiobook 1984 Orwell, George Audiobook 28 Summers Hilderbrand, Elin Audiobook Across That Bridge Lewis, John Audiobook All Systems Red: The Murderbot Diaries, Book 1 Wells, Martha Audiobook All the Devils Are Here Penny, Louise Audiobook Book of Lost Names Harmel, Kristin Audiobook Book of Two Ways Picoult, Jodi Audiobook Caste Wilkerson, Isabel Audiobook Chaos Johansen, Iris Audiobook Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator: Charlie Series, Book 2 Dahl, Roald Audiobook Charlotte's Web White, E. B. Audiobook Conditional Citizens Lalami, Laila Audiobook Darius the Great Deserves Better Khorram, Adib Audiobook Darius the Great Is Not Okay Khorram, Adib Audiobook Fast Break Lupica, Mike Audiobook Friendship List Mallery, Susan Audiobook Guest List Foley, Lucy Audiobook Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Rowling, J. K. Audiobook Hobbit Tolkien, J. R. R. Audiobook Hope in the Holler Tyre, Lisa Lewis Audiobook How to Fly Kingsolver, Barbara Audiobook I Survived the Attacks of September 11, 2001 Tarshis, Lauren Audiobook I'm Thinking of Ending Things Reid, Iain Audiobook Invention of Sound Palahniuk, Chuck Audiobook Invitation Foley, Lucy Audiobook Keeper of Lost Things Hogan, Ruth Audiobook Last Story of Mina Lee Kim, Nancy Jooyoun Audiobook Little Town on the Prairie: Little House Series, Book 7 Wilder, Laura Ingalls Audiobook Lost and Found Bookshop Wiggs, Susan Audiobook Lovecraft Country Ruff, Matt Audiobook Memory of Light Sanderson, Brandon Audiobook Midwife Murders Patterson, James Audiobook Momentous Events in the Life of a Cactus Bowling, Dusti Audiobook Murder Thy Neighbor Patterson, James Audiobook Narwhal on a Sunny Night Osborne, Mary Pope Audiobook No Offense Cabot, Meg Audiobook One and Only Bob Applegate, Katherine Audiobook Royal Steel, Danielle Audiobook Shadows in Death Robb, J. -

Video-Windows-Grosse

THEATRICAL VIDEO ANNOUNCEMENT TITLE VIDEO RELEASE VIDEO WINDOW GROSS (in millions) DISTRIBUTOR RELEASE ANNOUNCEMENT WINDOW DISNEY Fantasia/2000 1/1/00 8/24/00 7 mo 23 Days 11/14/00 10 mo 13 Days 60.5 Disney Down to You 1/21/00 5/31/00 4 mo 10 Days 7/11/00 5 mo 20 Days 20.3 Disney Gun Shy 2/4/00 4/11/00 2 mo 7 Days 6/20/00 4 mo 16 Days 1.6 Disney Scream 3 2/4/00 5/13/00 3 mo 9 Days 7/4/00 5 mo 89.1 Disney The Tigger Movie 2/11/00 5/31/00 3 mo 20 Days 8/22/00 6 mo 11 Days 45.5 Disney Reindeer Games 2/25/00 6/2/00 3 mo 8 Days 8/8/00 5 mo 14 Days 23.3 Disney Mission to Mars 3/10/00 7/4/00 3 mo 24 Days 9/12/00 6 mo 2 Days 60.8 Disney High Fidelity 3/31/00 7/4/00 3 mo 4 Days 9/19/00 5 mo 19 Days 27.2 Disney East is East 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 9/12/00 4 mo 29 Days 4.1 Disney Keeping the Faith 4/14/00 7/4/00 2 mo 16 Days 10/17/00 6 mo 3 Days 37 Disney Committed 4/28/00 9/7/00 4 mo 10 Days 10/10/00 5 mo 12 Days 0.04 Disney Hamlet 5/12/00 9/18/00 4 mo 6 Days 11/14/00 6 mo 2 Days 1.5 Disney Dinosaur 5/19/00 10/19/00 5 mo 1/30/01 8 mo 11 Days 137.7 Disney Shanghai Noon 5/26/00 8/12/00 2 mo 17 Days 11/14/00 5 mo 19 Days 56.9 Disney Gone in 60 Seconds 6/9/00 9/18/00 3 mo 9 Days 12/12/00 6 mo 3 Days 101.6 Disney Love’s Labour’s Lost 6/9/00 10/19/00 4 mo 10 Days 12/19/00 6 mo 10 Days 0.2 Disney Boys and Girls 6/16/00 9/18/00 3 mo 2 Days 11/14/00 4 mo 29 Days 21.7 Disney Disney’s The Kid 7/7/00 11/28/00 4 mo 21 Days 1/16/01 6 mo 9 Days 69.6 Disney Scary Movie 7/7/00 9/18/00 2 mo 11 Days 1212/00 5 mo 5 Days 157 Disney Coyote Ugly 8/4/00 11/28/00 3 -

ICFA 42 “Climate Change and the Anthropocene” Program V. 2021-03-14 9:30 EDT

1 ICFA 42 “Climate Change and the Anthropocene” Program v. 2021-03-14 9:30 EDT NB: PLEASE NOTE THAT IF YOU ARE REGISTERED FOR THE CONFERENCE, YOU HAVE BEEN SENT AN EMAIL THAT CONTAINS INFORMATION ABOUT THE LIVE LINKED PROGRAM. IF YOU DID NOT RECEIVE THE EMAIL, PLEASE CHECK YOUR SPAM FOLDER AS A LOT OF IAFA EMAILS ARE BEING SENT TO SPAM BY VARIOUS EMAIL ACCOUNTS. IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED, AND CHECKED YOUR SPAM FOLDER, AND STILL DO NOT SEE THE EMAIL, PLEASE LET US KNOW. Thursday, March 18, 2021- 10:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. Board Meeting [LIVE] Belle Isle ********** Thursday, March 18, 2021 - 11:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. BIPOC Meeting [LIVE] Magnolia ALL ARE WELCOME TO ATTEND. ********** Thursday, March 18, 2021 - 13:00 p.m. - 14:00 p.m. JFA Business Meeting [LIVE] Belle Isle SCIAFA Meeting [LIVE] Pine Lord Ruthven Assembly Meeting [LIVE] Magnolia ********** Thursday, March 18, 2021 - 15:00 p.m. – 16:00 p.m. SCIAFA Meet & Greet / Orientation [LIVE] Belle Isle ********** Thursday, March 18, 2021 16:00 p.m. - 18:00 p.m. Division Head Meeting [LIVE] Maple ********** 2 Friday, March 19, 2021 08:00 a.m. – 08:50 a.m. 1. (IF/SF/FTV/VPAA) [PRE RECORDED/UPLOADED] Weirding the Maple Anthropocene I: H.R. Giger, The Matrix, Volodine, and VanderMeer Chair: Dale Knickerbocker East Carolina University Decadence and Parasitism in the Anthropocene: An inquiry into the textual and surreal worlds of Weird Fiction, H.R. Giger and The Matric Trilogy of Films Arnab Chakraborty Independent Researcher Anthropocene Weirding in the Fiction of Antoine Volodine and Jeff VanderMeer Christina Lord University of North Carolina Wilmington 2. -

Coraline by Neil Gaiman

In the flat above Coraline's, under the roof, was Coraline a crazy old man with a big moustache. He told Coraline that he was training a mouse circus. He Neil Gaiman wouldn't let anyone see it. 1 ........................................................................................2 "One day, little Caroline, when they are all 2 ........................................................................................5 ready, everyone in the whole world will see the 3 ........................................................................................7 5 ......................................................................................15 wonders of my mouse circus. You ask me why 6 ......................................................................................20 you cannot see it now. Is that what you asked 7 ......................................................................................24 me?" 8 ......................................................................................26 9 ......................................................................................30 10 ....................................................................................33 "No," said Coraline quietly, "I asked you not to 11 ....................................................................................36 call me Caroline. It's Coraline." 12 ....................................................................................39 "The reason you cannot see the mouse circus," said the man upstairs, "is that the mice are not