High Conservation Value Forest (HCVF) Toolkit for Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Identity of Diplospora Africana (Rubiaceae)

The identity of Diplospora africana (Rubiaceae) E. Robbrecht Nationale Plantentuin van Belgie, Domein van Bouchout, Meise, Belgium Diplospora africana Sim is shown to be a distinct species Introduction belonging to Tricalysia subg. Empogona sect. Kraussiopsis. When Sim (1907) dealt with Tricalysia in the Cape, he did It possesses the characteristics of this subgenus: Flowers not follow the delimitation of the genus proposed in with densely hairy corolla throat and appendiculate anthers, and fruits black at complete maturity. The necessary Schumann's (1891) account of the family (i.e. Diplospora and combination under the name Tricalysia and an amplified Kraussia are considered as sections of Trica/ysia) , but description of the species are provided. This rather rare distinguished between Diplospora (with tetramerous flowers), species is a Pondoland endemic separated by a wide Kraussia (pentamerous) and Tricalysia (hexamerous), stating interval from its Guineo-Congolian relatives. A key to the that this artifical distinction 'probably does not hold good species of Trica/ysia in South Africa is provided; T. africana elsewhere'. Sim recognized five species in South Africa: D . is easily distinguished from the five other southern African Trica/ysia species by its tetramerous flowers. ajricana Sim, K. lanceo/ata Sand. [ = T. lanceolata (Sand.) S. Afr. J. Bot. 1985, 51: 331-334 Burtt-Davy], K. jloribunda Harv., K. coriacea Sond. ( = T. sonderana Hiern) and T. capensis (Meisn.) Sim. While the Diplospora africana Sim is 'n maklik onderskeidbare spesie last four species are now well known elements of the South wat in Tricalysia subg. Empogona sect. Kraussiopsis African flora, Dip/ospora ajricana remained obscure and ingesluit word. -

Taxanomic Composition and Conservation Status of Plants in Imbak Canyon, Sabah, Malaysia

Journal of Tropical Biology and Conservation 16: 79–100, 2019 ISSN 1823-3902 E-ISSN 2550-1909 Short Notes Taxanomic Composition and Conservation Status of Plants in Imbak Canyon, Sabah, Malaysia Elizabeth Pesiu1*, Reuben Nilus2, John Sugau2, Mohd. Aminur Faiz Suis2, Petrus Butin2, Postar Miun2, Lawrence Tingkoi2, Jabanus Miun2, Markus Gubilil2, Hardy Mangkawasa3, Richard Majapun2, Mohd Tajuddin Abdullah1,4 1Institute of Tropical Biodiversity and Sustainable Development, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, 21030, Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu 2Forest Research Centre, Sabah Forestry Department, Sandakan, Sabah, Malaysia 3 Maliau Basin Conservation Area, Yayasan Sabah 4Faculty of Science and Marine Environment, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, 21030, Kuala Terengganu *Corresponding authors: [email protected] Abstract A study of plant diversity and their conservation status was conducted in Batu Timbang, Imbak Canyon Conservation Area (ICCA), Sabah. The study aimed to document plant diversity and to identify interesting, endemic, rare and threatened plant species which were considered high conservation value species. A total of 413 species from 82 families were recorded from the study area of which 93 taxa were endemic to Borneo, including 10 endemic to Sabah. These high conservation value species are key conservation targets for any forested area such as ICCA. Proper knowledge of plant diversity and their conservation status is vital for the formulation of a forest management plan for the Batu Timbang area. Keywords: Vascular plant, floral diversity, endemic, endangered, Borneo Introduction The earth as it is today has a lot of important yet beneficial natural resources such as tropical forests. Tropical forests are one of the world’s richest ecosystems, providing a wide range of important natural resources comprising vital biotic and abiotic components (Darus, 1982). -

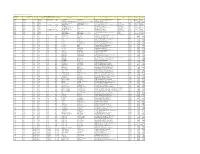

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

The Vulnerability of Bajau Laut (Sama Dilaut) Children in Sabah, Malaysia

A position paper on: The vulnerability of Bajau Laut (Sama Dilaut) children in Sabah, Malaysia Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN) 888/12, 3rd Floor Mahatun Plaza, Ploenchit Road Lumpini, Pratumwan 10330 Bangkok, Thailand Tel: +66(0)2-252-6654 Fax: +66(0)2-689-6205 Website: www.aprrn.org The vulnerability of Bajau Laut (Sama Dilaut) children in Sabah, Malaysia March 2015 Background Statelessness is a global man-made phenomenon, variously affecting entire communities, new-born babies, children, couples and older people, and can occur because of a bewildering array of causes. According to UNHCR, at least 10 million people worldwide have no nationality. While stateless people are entitled to human rights under international law, without a nationality, they often face barriers that prevent them from accessing their rights. These include the right to establish a legal residence, travel, work in the formal economy, access education, access basic health services, purchase or own property, vote, hold elected office, and enjoy the protection and security of a country. The Bajau Laut (who often self-identify as Sama Dilaut and are referred to by others as ‘Pala’uh’) are arguably some of the most marginalised people in Malaysia. Despite records of their presence in the region dating back for centuries, today many Bajau Laut have no legal nationality documents bonding them to a State, are highly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. The Bajau Laut are a classic example of a protracted and intergenerational statelessness situation. Children, the majority of whom were born in Sabah and have never set foot in another country, are particularly at risk. -

Flora of Singapore Precursors, 9: the Identities of Two Unplaced Taxa Based on Types from Singapore

Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 70 (2): 295–299. 2018 295 doi: 10.26492/gbs70(2).2018-06 Flora of Singapore precursors, 9: The identities of two unplaced taxa based on types from Singapore I.M. Turner1, 2, M. Rodda2, K.M. Wong2 & D.J. Middleton2 1Singapore Botanical Liaison Officer, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AE, U.K. [email protected] 2Singapore Botanic Gardens, National Parks Board, 1 Cluny Road, 259569, Singapore. ABSTRACT. Work on the Gentianales for the Flora of Singapore has clarified the identities of two names based on types collected in Singapore that have long been considered of uncertain application. Dischidia wallichii Wight is shown to be a synonym of Micrechites serpyllifolius (Blume) Kosterm. (Apocynaceae) and Saprosma ridleyi King & Gamble is a synonym of Psychotria maingayi Hook.f. (Rubiaceae). A lectotype is designated for Dischidia wallichii. Keywords. Apocynaceae, Dischidia wallichii, Micrechites serpyllifolius, Psychotria maingayi, Rubiaceae, Saprosma ridleyi, synonymy Introduction The Gentianales have recently been the focus of intensive research in preparation for the accounts of the included families for the Flora of Singapore (Rodda & Ang, 2012; Rodda et al., 2015, 2016; Middleton et al., 2018; Rodda & Lai, 2018; Seah & Wong, 2018; Turner, 2018; Turner & Kumar, 2018; Wong & Mahyuni, 2018; Wong et al, in press; Wong & Lua, 2018). This involved a closer look at two taxa described from specimens collected in Singapore that have long eluded satisfactory conclusions as to their identities, Dischidia wallichii Wight (Apocynaceae) and Saprosma ridleyi King & Gamble (Rubiaceae). Through a collaboration among the authors of this paper, who have wide expertise across these families, we can now place these two names in synonymy of other taxa. -

The Executive Survey General Information and Guidelines

The Executive Survey General Information and Guidelines Dear Country Expert, In this section, we distinguish between the head of state (HOS) and the head of government (HOG). • The Head of State (HOS) is an individual or collective body that serves as the chief public representative of the country; his or her function could be purely ceremonial. • The Head of Government (HOG) is the chief officer(s) of the executive branch of government; the HOG may also be HOS, in which case the executive survey only pertains to the HOS. • The executive survey applies to the person who effectively holds these positions in practice. • The HOS/HOG pair will always include the effective ruler of the country, even if for a period this is the commander of foreign occupying forces. • The HOS and/or HOG must rule over a significant part of the country’s territory. • The HOS and/or HOG must be a resident of the country — governments in exile are not listed. • By implication, if you are considering a semi-sovereign territory, such as a colony or an annexed territory, the HOS and/or HOG will be a person located in the territory in question, not in the capital of the colonizing/annexing country. • Only HOSs and/or HOGs who stay in power for 100 consecutive days or more will be included in the surveys. • A country may go without a HOG but there will be no period listed with only a HOG and no HOS. • If a HOG also becomes HOS (interim or full), s/he is moved to the HOS list and removed from the HOG list for the duration of their tenure. -

Vascular Plant Composition and Diversity of a Coastal Hill Forest in Perak, Malaysia

www.ccsenet.org/jas Journal of Agricultural Science Vol. 3, No. 3; September 2011 Vascular Plant Composition and Diversity of a Coastal Hill Forest in Perak, Malaysia S. Ghollasimood (Corresponding author), I. Faridah Hanum, M. Nazre, Abd Kudus Kamziah & A.G. Awang Noor Faculty of Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia 43400, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Tel: 98-915-756-2704 E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 7, 2010 Accepted: September 20, 2010 doi:10.5539/jas.v3n3p111 Abstract Vascular plant species and diversity of a coastal hill forest in Sungai Pinang Permanent Forest Reserve in Pulau Pangkor at Perak were studied based on the data from five one hectare plots. All vascular plants were enumerated and identified. Importance value index (IVI) was computed to characterize the floristic composition. To capture different aspects of species diversity, we considered five different indices. The mean stem density was 7585 stems per ha. In total 36797 vascular plants representing 348 species belong to 227 genera in 89 families were identified within 5-ha of a coastal hill forest that is comprises 4.2% species, 10.7% genera and 34.7% families of the total taxa found in Peninsular Malaysia. Based on IVI, Agrostistachys longifolia (IVI 1245), Eugeissona tristis (IVI 890), Calophyllum wallichianum (IVI 807), followed by Taenitis blechnoides (IVI 784) were the most dominant species. The most speciose rich families were Rubiaceae having 27 species, followed by Dipterocarpaceae (21 species), Euphorbiaceae (20 species) and Palmae (14 species). According to growth forms, 57% of all species were trees, 13% shrubs, 10% herbs, 9% lianas, 4% palms, 3.5% climbers and 3% ferns. -

24 Mac 1986 1488

Jilid IV fi Hari Isnin Bit, 10 ' 24hb Mac, 1986 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RAKYAT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES PARLIMEN KEENAM Sixth Parliament PENGGAL KEEMPAT Fourth Session KANDUNGANNYA JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [Ruangan 1501] USUL: Rancangan Malaysia Kelima 1986-1990 [Ruangan 1552] DICETAK OLEH JABATAN PERCETAKAN NEGARA, KUALA LUMPUR HAJI MOKHTAR SHAMSUDDIN , J.S.D., S.M.T., S.M.S., K.M.N., P.I.S. KETUA PENGARAH 1986 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KEENAM Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG KEEMPAT AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATO' MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAJI ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Pertahanan, DATO' SERI DR MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, S.S.D.K., S.S.A.P ., S.P.M.S ., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., S.P.C. M., S.S.M .T., D.U.N.M. (Kubang Pasu). Yang Berhormat Menteri Kerjaraya, DATO' S. SAMY VELLU, S.P.M.J ., D.P.M.S., P.C.M., A.M.N. (Sungei Siput). „ Menteri Luar Negeri, Y.B.M. TENGKU DATO' AHMAD RITHAUDDEEN AL-HAJ BIN TENGKU ISMAIL, S.P.M.P., S.S.A.P., P.M.K. (Kota Bharu). „ Menteri Perdagangan dan Perindustrian, Y.B.M. TENGKU TAN SRI RAZALEIGH HAMZAH, D.K., P.S. M., S.P.M . K., S.S.A . P., S.P.M.S. (Ulu Kelantan). „ Menteri Perusahaan Utama, DATO' PAUL LEONG KHEE SEONG, D.P.C.M. -

Senarai Pakar/Pegawai Perubatan Yang Mempunyai Nombor Pendaftaran Pemeriksaan Kesihatan Bakal Haji Bagi Musim Haji 1440H / 2019M

SENARAI PAKAR/PEGAWAI PERUBATAN YANG MEMPUNYAI NOMBOR PENDAFTARAN PEMERIKSAAN KESIHATAN BAKAL HAJI BAGI MUSIM HAJI 1440H / 2019M HOSPITAL & KLINIK KERAJAAN NEGERI PAHANG TEMPAT BERTUGAS BIL NAMA DOKTOR (ALAMAT LENGKAP HOSPITAL & DAERAH KLINIK) 1. Dr. Wan Atiqah Binti Wan Abd Rashid KLINIK KESIHATAN BUKIT GOH Kuantan Kuantan 26050 Kuantan 2. Dr. Siti Qariah Binti Adam KLINIK KESIHATAN KURNIA Kuantan Batu 3 Jalan Gambang 25150 Kuantan 3. Dr. Sazali Bin Salleh HOSPITAL TENGKU AMPUAN AFZAN Kuantan Jabatan Ortopedik Jalan Tanah Putih 25150 KUANTAN 4. Dr. Nurul Syahidah Binti Mansor KLINIK KESIHATAN INDERA MAHKOTA Kuantan Jalan IM4, Bandar Indera Mahkota 25582 Kuantan 5. Dr. Nursiah Binti Muhd Dom KLINIK KESIHATAN BANDAR KUANTAN Kuantan Jalan Bukit Sekilau 25200 Kuantan 6. Dr. Nurhanis Binti Ahmran KLINIK KESIHATAN BALOK Kuantan Balok 26100 Kuantan SENARAI PAKAR/PEGAWAI PERUBATAN YANG MEMPUNYAI NOMBOR PENDAFTARAN PEMERIKSAAN KESIHATAN BAKAL HAJI BAGI MUSIM HAJI 1440H / 2019M HOSPITAL & KLINIK KERAJAAN NEGERI PAHANG TEMPAT BERTUGAS BIL NAMA DOKTOR (ALAMAT LENGKAP HOSPITAL & DAERAH KLINIK) 7 Dr. Nurhamidah Binti Kamarudin KLINIK KESIHATAN GAMBANG Kuantan Jalan Gambang 26300 Kuantan 8 Dr. Noorazida Zaharah Binti Mansor HOSPITAL TENGKU AMPUAN AFZAN Kuantan Jabatan Psikiatari Jalan Tanah Putih 25150 Kuantan 9 Dr. Noor Ashikin Binti Johari KLINIK KESIHATAN PAYA BESAR Kuantan Jalan Pintasan Kuantan-Gambang 25100 Kuantan 10 Dr. Mohd Daud Bin Che Yusof KLINIK KESIHATAN BESERAH Kuantan Jalan Beserah 26100 KUANTAN 11 Dr. Megat Razeem Bin Abdul Razak HOSPITAL TENGKU AMPUAN AFZAN Kuantan Jabatan Perubatan Jalan Tanah Putih 25150 KUANTAN 12 Dr. Jannatul Raudha Binti Azmi KLINIK KESIHATAN BUKIT GOH Kuantan Kuantan 26050 Kuantan SENARAI PAKAR/PEGAWAI PERUBATAN YANG MEMPUNYAI NOMBOR PENDAFTARAN PEMERIKSAAN KESIHATAN BAKAL HAJI BAGI MUSIM HAJI 1440H / 2019M HOSPITAL & KLINIK KERAJAAN NEGERI PAHANG TEMPAT BERTUGAS BIL NAMA DOKTOR (ALAMAT LENGKAP HOSPITAL & DAERAH KLINIK) 13 Dr. -

Diplospora Should Be Separated From

BLUMEA 35 (1991) 279-305 Remarks on the tropical Asian and Australian taxa included in Diplospora or Tricalysia (Rubiaceae — Ixoroideae — Gardenieae) S.J. Ali & E. Robbrecht Summary The Asian and Australian species generally included in Diplospora or Tricalysia are shown to form an artificial assemblage. A few species even do not belong to the Gardenieae-Diplosporinae and need to be transferred to other tribes of the Ixoroideae. So Diplospora malaccensis, Diplospora and the The minahassae, Tricalysia purpurea, Tricalysia sorsogonensis belong to Hypobathreae. three Australian members of the Pavetteae and transferred Tarenna. A Diplosporas are are to survey is given of the characters of the remaining Asian species of Diplospora/Tricalysia, demonstrating that these be accommodated under the African and 1) species cannot genus Tricalysia, 2)Discosper- mum, since a century included in the synonymy ofDiplospora, merits to be revived at generic rank. The differ in fruit size and fruit wall two genera placentation, texture, number of seeds per locule, seed and exotestal cell combinations shape, anatomy. Eight necessary new are provided: Diplospora puberula, Diplospora tinagoensis, Discospermum abnorme, Discospermum beccarianum,Discosper- mum whitfordii, Tarenna australis, Tarenna cameroni, and Tarenna triflora. An annotated check-list including the more than 100 names involved is given. 1. Introduction Present undertaken short-time study, as a postdoctoral research of the first author, intends to settle the problem of the generic position of the Asian species included in Tricalysia or Diplospora (Rubiaceae-Ixoroideae-Gardenieae-Diplosporinae). In- deed, it is not clear whether the Asian genus Diplospora should be separated from Tricalysia or not. Robbrecht (1979, 1982, 1983, 1987), when revising the African species of Tricalysia, left the question unanswered. -

The Genus Koilodepas Hassk. (Euphorbiaceae) in Malesia

B I O D I V E R S I T A S ISSN: 1412-033X Volume 5, Nomor 2 Juli 2004 Halaman: 52-60 The Genus Koilodepas Hassk. (Euphorbiaceae) in Malesia MUZAYYINAH1,♥, EDI GUHARDJA2, MIEN A. RIFAI3, JOHANIS P. MOGEA3, PETER VAN WALZEN4 1Program Study of Biological Education, Department of PMIPA FKIP Sebelas Maret University Surakarta 57126, Indonesia. 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematic and Sciences, Bogor Agriculture University, Bogor Indonesia 3"Herbarium Bogoriense", Department of Botany, Research Center of Biology -LIPI, Bogor 16013, Indonesia 4Rijksherbarium Leiden, The Netherlands. Received: 8th December 2003. Accepted: 17th May 2004. ABSTRACT The Malesian genus Koilodepas Hassk. has been revised based on the morphological and anatomical character using available herbarium collection in Herbarium Bogoriense and loan specimens from Kew Herbarium and Leiden Rijksherbarium. The present study is based on the observation of 176 specimens. Eight species has been recognized, namely K. bantamense, K. cordifolium, K. frutescns, K. homalifolium, K. laevigatum, K. longifolium, K. pectinatum, and two varieties within K. brevipes. The highest number of species is found in Borneo (5 species), three of them are found endemically in Borneo, K. cordisepalum endemically in Aceh, and K. homalifolium endemically in Papua New Guinea. A phylogenetic analysis of the genus, with Cephalomappa as outgroup, show that the species within the genus Koilodepas is in one group, starting with K. brevipes as a primitive one and K. bantamense occupies in an advance position. 2004 Jurusan Biologi FMIPA UNS Surakarta Keyword: Koilodepas Hassk., Malesia, outgroup, phylogenetic analysis, outgroup. INTRODUCTION Methods The methods of research were morphological and The genus Koilodepas belongs to the tribe Epipri- leaf-anatomical description. -

Key to the Families and Genera of Malesian <I>Euphorbiaceae</I> in the Wide Sense

Blumea 65, 2020: 53–60 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2020.65.01.05 Key to the families and genera of Malesian Euphorbiaceae in the wide sense P.C. van Welzen1,2 Key words Abstract Identification keys are provided to the different families in which the Euphorbiaceae are split after APG IV. Presently, Euphorbiaceae in the strict sense, Pandaceae, Peraceae, Phyllanthaceae, Picrodendraceae and Euphorbiaceae Putranjivaceae are distinguished as distinct families. Within the families, keys to the different genera occurring in the keys Malesian area, native and introduced, are presented. The keys are to be tested and responses are very welcome. Pandaceae Peraceae Published on 3 April 2020 Phyllanthaceae Picrodendraceae Putranjivaceae INTRODUCTION KEY TO THE EUPHORBIACEOUS FAMILIES The Euphorbiaceae in the wide sense (sensu lato, s.lat.) were 1. Ovary with a single ovule per locule . 2 always a heterogeneous group without any distinct combination 1. Ovary with two ovules per locule ................... 4 of characters. The most typical features are the presence of uni- 2. Fruits drupes. Flowers of both sexes with petals . sexual simple flowers and fruits that fall apart in various carpel ...................................2. Pandaceae fragments and seeds, leaving the characteristic columella on the 2. Fruits capsules, sometimes drupes or berries, then flowers plant. However, some groups, like the Pandaceae and Putranji of both sexes lacking petals.......................3 vaceae, were morphologically already known to be quite unlike 3. Herbs, shrubs, lianas, trees, mono- or dioecious. Flowers in the rest of the Euphorbiaceae s.lat. (e.g., Radcliffe-Smith 1987). cauliflorous, ramiflorous, axillary, or terminal inflorescences The Putranjivaceae formerly formed the tribe Drypeteae in the ................................1.