A Conversation with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justices' Profiles Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Supreme Court Preview Conferences, Events, and Lectures 1995 Section 1: Justices' Profiles Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School, "Section 1: Justices' Profiles" (1995). Supreme Court Preview. 35. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview/35 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview WARREN E. BURGER IS DEAD AT 87 Was Chief Justice for 17 Years Copyright 1995 The New York Times Company The New York Times June 26, 1995, Monday Linda Greenhouse Washington, June 25 - Warren E. Burger, who retired to apply like an epithet -- overruled no major in 1986 after 17 years as the 15th Chief Justice of the decisions from the Warren era. United States, died here today at age 87. The cause It was a further incongruity that despite Chief was congestive heart failure, a spokeswoman for the Justice Burger's high visibility and the evident relish Supreme Court said. with which he used his office to expound his views on An energetic court administrator, Chief Justice everything from legal education to prison Burger was in some respects a transitional figure management, scholars and Supreme Court despite his tenure, the longest for a Chief Justice in commentators continued to question the degree to this century. He presided over a Court that, while it which he actually led the institution over which he so grew steadily more conservative with subsequent energetically presided. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E812 HON

E812 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 30, 2009 Engine Repair Shop. The USS Tutuila func- of the Year by the United States Track & Field tion on Florida folk life while working for the tioned as a repair ship for the hundreds of and Cross Country Coaches Association WPA’s Federal Writers Project. As a result of small armed craft, or swift boats, used by the (USTFCCCA). her extensive anthropological research, her U.S. Navy and their South Vietnamese coun- Overall, the win marks SUNY Cortland’s writings have become invaluable sources on terparts in patrolling the numerous inland and 22nd national team title, including 16 NCAA African American life during the Harlem Ren- coastal waterways. Mr. Nissen and his fellow crowns in seven different sports. aissance. In all, Hurston wrote four novels and sailors worked around the clock to keep the Madam Speaker, I am honored to represent more than 50 published short stories, plays, swift boats functioning. They were often re- such skilled and hard-working athletes in my and essays, and she is best known for her sponsible for towing boats out of hostile areas district. Please join me in congratulating the 1937 novel ‘‘Their Eyes Were Watching God.’’ and transporting wounded sailors to safety. team and wishing them the best of luck in Madam Speaker, I would also like to recog- During his service on the USS Tutuila, Mr. their future athletic and scholarly pursuits. nize Dr. Gladys Pumariega Soler. Dr. Soler Nissen became interested in the work of the f was born in Cuba in 1930 and earned a med- medical staff and became a ‘‘striker’’ for a rat- ical degree from Havana University in 1955. -

Lessons Learned from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

LESSONS LEARNED FROM JUSTICE RUTH BADER GINSBURG Amanda L. Tyler* INTRODUCTION Serving as a law clerk for Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the Supreme Court’s October Term 1999 was one of the single greatest privileges and honors of my life. As a trailblazer who opened up opportunities for women, she was a personal hero. How many people get to say that they worked for their hero? Justice Ginsburg was defined by her brilliance, her dedication to public service, her resilience, and her unwavering devotion to taking up the Founders’ calling, set out in the Preamble to our Constitution, to make ours a “more perfect Union.”1 She was a profoundly dedicated public servant in no small measure because she appreciated just how important her role was in ensuring that our Constitution belongs to everyone. Whether as an advocate or a Justice, she tirelessly fought to dismantle discrimination and more generally to open opportunities for every person to live up to their full human potential. Without question, she left this world a better place than she found it, and we are all the beneficiaries. As an advocate, Ruth Bader Ginsburg challenged our society to liber- ate all persons from the gender-based stereotypes that held them back. As a federal judge for forty years—twenty-seven of them on the Supreme Court—she continued and expanded upon that work, even when it meant in dissent calling out her colleagues for improperly walking back earlier gains or halting future progress.2 In total, she wrote over 700 opinions on the D.C. -

Does Eliminating Life Tenure for Article Iii Judges Require a Constitutional Amendment?

DOW & MEHTA_03_15_21 (DO NOT DELETE) 3/17/2021 6:41 PM DOES ELIMINATING LIFE TENURE FOR ARTICLE III JUDGES REQUIRE A CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT? DAVID R. DOW & SANAT MEHTA* ABSTRACT Beginning in the early 2000s, a number of legal academicians from across the political spectrum proposed eliminating life tenure for some or all Article III judges and replacing it with a term of years (or a set of renewable terms). These scholars were largely in agreement such a change could be accomplished only by a formal constitutional amendment of Article III. In this Article, Dow and Mehta agree with the desirability of doing away with life tenure but argue such a change can be accomplished by ordinary legislation, without the need for formal amendment. Drawing on both originalism and formalism, Dow and Mehta begin by observing that the constitutional text does not expressly provide for lifetime tenure; rather, it states that judges shall hold their office during good behavior. The good behavior criterion, however, was not intended to create judicial sinecures for 20 or 30 years, but instead aimed at safeguarding judicial independence from the political branches. By measuring both the length of judicial tenure among Supreme Court justices, as well as voting behavior on the Supreme Court, Dow and Mehta conclude that, in fact, life tenure has proven inconsistent with judicial independence. They maintain that the Framers’ objective of insuring judicial independence is best achieved by term limits for Supreme Court justices. Copyright © 2021 David R. Dow & Sanat Mehta. * David Dow is the Cullen Professor at the University of Houston Law Center; Sanat Mehta, who graduated magna cum laude from Rice University in 2020 with a degree in computer science and a minor in Politics, Law, and Social Thought, is a data analyst at American Airlines. -

The US Supreme Court and Criminal Justice Policy

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 The mpI act of New Justices: The .SU . Supreme Court and Criminal Justice Policy Christopher E. Smith Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Judges Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Christopher E. (1997) "The mpI act of New Justices: The .SU . Supreme Court and Criminal Justice Policy," Akron Law Review: Vol. 30 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol30/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Smith: The U.S. Supreme Court and Criminal Justice Policy The Impact of New Justices: The U.S. Supreme Court and Criminal Justice Policy by * Christopher E. Smith I. Introduction The Supreme Court is an important policy-making institution. In criminal justice,1 for example, the high court issues decisions affecting institutions, actors, and processes throughout the justice system, from police investigations2 through corrections and parole.3 The Court's policy decisions affecting criminal justice are produced by the votes of the nine justices who select, hear, decide, and issue opinions in cases. -

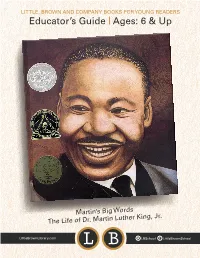

Educator's Guide | Ages: 6 & Up

LIT TLE, BROWN AND COMPANY BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS Educator’s Guide | Ages: 6 & Up Martin’s Big Words The Life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. LittleBrownLibrary.com LBSchool LittleBrownSchool Martin’s Big Words Pre-Reading With a small group, discuss questions about leaders. What is a leader? What does a person do to become a leader? What makes a good leader? Genre We study biographies to learn from the lives of others. Why is Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., an important person to read about? What can we learn from the way he lived his life? The author inserted many of Dr. King’s own words throughout the text. Why do you think this was an important thing to do? Pick one quote and explain the significance. Theme: Equality The civil rights movement worked to create equal opportunities for African American people. What are some specific examples in education, employment, and public settings that needed to change for equality? Use the book to provide specific examples that support001-040_MBW_C75362.indd your 11 JOB NO:06-97121 TITLE:MARTIN’S BIG WORDS 1/5/16 10:50 AM 12-AC75362 #150 (JBRD) DTP:44 PAGE:11 answer. Are there still things that need to be changed? Setting What are the major settings in the biography of Dr. King? Which illustrations give you a clue that it is in a time different from today? What part of the country did most of Dr. King’s work focus on? Why? Show where you found your answer in the text. Across the Curriculum Language Arts Use technology to research another hero or major figure of the civil rights movement and write a biography. -

(Candace Fleming) B EARHART O Tells the Story of Amelia Earhart's Life - As a Child, a Woman, and a Pilot - and Describes the Search for Her Missing Plane

Real Life Rebels Amelia Lost: The life and Disappearance of Amelia Earhart (Candace Fleming) B EARHART o Tells the story of Amelia Earhart's life - as a child, a woman, and a pilot - and describes the search for her missing plane. Bad Girls: Sirens, Jezebels, Murderesses, Thieves & other Female Villains (Jane Yolen) 920.72 Y o Harlot or hero? Liar or lady? There are two sides to every story. Meet twenty-six of history's most notorious women, and debate alongside authors Yolen and Stemple--who appear in the book as themselves in a series of comic panels--as to each girl's guilt or innocence. Being Jazz: My Life as a Transgender Teen (Jazz Jennings) B JENNINGS o Teen activist and trailblazer Jazz Jennings--named one of "The 25 most influential teens" of the year by Time--shares her very public transgender journey, as she inspires people to accept the differences in others while they embrace their own truths. Brown Girl Dreaming (Jacqueline Woodson) B WOODSON o The author shares her childhood memories and reveals the first sparks that ignited her writing career in free-verse poems about growing up in the North and South Claudette Colvin: Twice Toward Justice (Phillip Hoose) CD 323.092 H o On March 2, 1955, a slim, bespectacled teenager refused to give up her seat to a white woman on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Shouting 'It's my constitutional right!' as police dragged her off to jail, Claudette Colvin decided she'd had enough of the Jim Crow segregation laws that had angered and puzzled her since she was a young child. -

Celebrating Women's History Month

March 2021 - Celebrating Women’s History Month It all started with a single day in 1908 in New York City when thousands of women marched for better labor laws, conditions, and the right to vote. A year later on February 28, in a gathering organized by members of the Socialist Party, suffragists and socialists gathered again in Manhattan for what they called the first International Woman’s Day. The idea quickly spread worldwide from Germany to Russia. In 1911, 17 European countries formally honored the day as International Women’s day. By 1917 with strong influences and the beginnings of the Russian Revolution communist leader Vladimir Lenin made Women’s Day a soviet holiday. But due to its connections to socialism and the Soviet Union, the holiday wasn’t largely celebrated in the United States until 1975. That’s when the United Nations officially began sponsoring International Woman’s day. In 1978 Woman’s Day grew from a day to a week as the National Women’s History Alliance became frustrated with the lack of information about women’s history available to public school curriculums. Branching off of the initial celebration, they initiated the creation of Women’s History week. And by 1980 President Jimmy Carter declared in a presidential proclamation that March 8 was officially National Women’s History Week. As a result of its country wide recognition and continued growth in state schools, government, and organizations by 1986, 14 states had gone ahead and dubbed March Women’s History Month. A year later, this sparked congress to declare the holiday in perpetuity. -

Janet Reno, First Female US Attorney General, Dies

6A » Tuesday, November 8, 2016 » KITSAPSUN MONEY LIFE MONDAY MARKETS GOOD DAYFOR LORDE FANS INDEX CLOSE CHG DowJones Industrial Avg. 18,260 x 371.32 On the eve of her 20th birthday,the Nasdaq composite 5,166.17 x 119.80 pop idol offered asmall gift to fans: S&P 500 2,131.52 x 46.34 The promise of new music. “I want you T-note,10-year yield 1.83% x 0.06 Oil, light sweet crude $44.89 x 0.82 to see the album cover,poreover the Euro(dollarsper euro) $1.1040 y 0.0077 lyrics (the best I’ve written in my life), Yenper dollar 104.58 x 1.45 touch the merch, experiencethe live SOURCES USA TODAYRESEARCH, MARKETWATCH.COM show,” Lorde wrote in an open letter vAmericasMarkets.usatoday.com KEVIN WINTER/GETTY IMAGES published late Sunday. Nation &World Watch JanetReno,firstfemale From Gannett and wirereports vCushing, Okla.: Quake US attorneygeneral, dies damages 40-50 buildings Dozens of buildings sustained “sub- stantial damage” after a5.0-magnitude earthquakestruck an Oklahoma town ‘Fiercely independent’ leader headed Justice through tough times that’shome to one of the world’skey oil hubs,but officials said Mondaythat no Jane Onyanga-Omara damagewas reported at the oil terminal. and Kevin Johnson Cushing City Manager SteveSpears said 40 to 50 buildings were damaged in USA TODAY Sunday’searthquake, which wasthe third in Oklahoma this year with amag- JanetReno,the firstwoman nitude of 5.0orgreater.Oklahoma has to serveasU.S.attorney gener- had thousands of earthquakes in recent al, whose tenure spanned some years,with nearly all traced to the under- of the mosttumultuous periods ground injection of wastewater left over in American life, has died. -

Justice Sandra Day O'connor: the World's Most Powerful Jurist?

JUSTICE SANDRA DAY O'CONNOR: THE WORLD'S MOST POWERFUL JURIST? DIANE LOWENTHAL AND BARBARA PALMER* I. INTRODUCTION Justice Sandra Day O'Connor has been called a "major force on [the] Supreme Court,"' the "real" Chief Justice, 2 and "America's most powerful jurist."' 3 Others have referred to her as "the most 5 powerful woman in America" 4 and even of "the world.", Even compared to women like Eleanor Roosevelt and Hillary Clinton, there is no one "who has had a more profound effect on society than any other American woman... If someone else had been appointed to her position on the court, our nation might now be living under different rules for abortion, affirmative action, race, religion in school and civil rights. We might well have a different president." 6 Former Acting Solicitor General Walter Dellinger noted, "What is most striking is the assurance with which this formerly obscure state court judge effectively decides many hugely important questions for a country of 275 million people.",7 As one journalist put it, "We are all living in * Diane Lowenthal, Ph.D. in Social and Decision Sciences, Carnegie Mellon University and Barbara Palmer, Ph.D. in Political Science, University of Minnesota, are assistant professors in American University's Washington Semester Program. The authors would like to thank their undergraduate research assistants, Amy Bauman, Nick Chapman-Hushek, and Amanda White. This paper was presented at October 28, 2004 Town Hall The Sway of the Swing Vote: Justice Sandra Day O'Connor and Her Influence on Issues of Race, Religion, Gender and Class sponsored by the University of Maryland Law Journal of Race, Religion, Gender and Class and the Women, Leadership and Equality Program. -

Florida Women's Heritage Trail Sites 26 Florida "Firsts'' 28 the Florida Women's Club Movement 29 Acknowledgements 32

A Florida Heritag I fii 11 :i rafiM H rtiS ^^I^H ^bIh^^^^^^^Ji ^I^^Bfi^^ Florida Association of Museums The Florida raises the visibility of muse- Women 's ums in the state and serves as Heritage Trail a liaison between museums ^ was pro- and government. '/"'^Vm duced in FAM is managed by a board of cooperation directors elected by the mem- with the bership, which is representa- Florida tive of the spectrum of mu- Association seum disciplines in Florida. of Museums FAM has succeeded in provid- (FAM). The ing numerous economic, Florida educational and informational Association of Museums is a benefits for its members. nonprofit corporation, estab- lished for educational pur- Florida Association of poses. It provides continuing Museums education and networking Post Office Box 10951 opportunities for museum Tallahassee, Florida 32302-2951 professionals, improves the Phone: (850) 222-6028 level of professionalism within FAX: (850) 222-6112 the museum community, www.flamuseums.org Contact the Florida Associa- serves as a resource for infor- tion of Museums for a compli- mation Florida's on museums. mentary copy of "See The World!" Credits Author: Nina McGuire The section on Florida Women's Clubs (pages 29 to 31) is derived from the National Register of Historic Places nomination prepared by DeLand historian Sidney Johnston. Graphic Design: Jonathan Lyons, Lyons Digital Media, Tallahassee. Special thanks to Ann Kozeliski, A Kozeliski Design, Tallahassee, and Steve Little, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee. Photography: Ray Stanyard, Tallahassee; Michael Zimny and Phillip M. Pollock, Division of Historical Resources; Pat Canova and Lucy Beebe/ Silver Image; Jim Stokes; Historic Tours of America, Inc., Key West; The Key West Chamber of Commerce; Jacksonville Planning and Development Department; Historic Pensacola Preservation Board. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E865 HON. SHEILA JACKSON

September 21, 2020 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E865 Fairness Act. I had intended to vote ‘‘no’’ on ner at his family home and asked the female every respect, that they could have successful roll call vote 194, against the Motion to law students, including Ginsburg, ‘‘Why are careers and also could, if they chose, be de- Recommit. you at Harvard Law School, taking the place voted wives or mothers, thereby breaking bar- f of a man?’’ riers for generations of women to follow in her When her husband took a job in New York footsteps. IN REMEMBRANCE OF THE HONOR- City, Ruth Bader Ginsburg transferred to Co- In fact, many of Ginsburg’s opinions helped ABLE RUTH BADER GINSBURG, lumbia Law School and became the first solidify the constitutional protections she had THE ‘NOTORIOUS RBG,’ ASSO- woman to be on two major law reviews: Har- fought so hard to establish decades earlier. CIATE JUSTICE OF THE SU- vard Law Review and Columbia Law Review. While we commemorate Justice Ginsburg’s PREME COURT, FEMINIST ICON In 1959, she earned her law degree at Co- work for advancing the women’s movement AND TRAILBLAZER, INSPIRATION lumbia and tied for first in her class but de- both as a Justice and as a lawyer, all are in TO MILLIONS, TIRELESS CHAM- spite these enviable credentials and distin- her debt who cherish the progress made in PION FOR JUSTICE AND FIERCE guished record of excellence, no law firm in the areas of LGBTQ+ equality, immigration re- DEFENDER OF THE CONSTITU- New York City would hire as a lawyer because form, environmental justice, voting rights, pro- TION she was a woman.