Chios-Theodoulou2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Current Organization and Administration Situation of the Secondary Education Units in the North Aegean Region

ISSN 2664-4002 (Print) & ISSN 2664-6714 (Online) South Asian Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: South Asian Res J Human Soc Sci | Volume-1 | Issue-4| Dec -2019 | DOI: 10.36346/sarjhss.2019.v01i04.010 Original Research Article The Current Organization and Administration Situation of the Secondary Education Units in the North Aegean Region Dimitrios Ntalossis, George F. Zarotis* University of the Aegean, Faculty of Human Sciences, Rhodes, Greece *Corresponding Author Dr. George F. Zarotis Article History Received: 14.12.2019 Accepted: 24.12.2019 Published: 30.12.2019 Abstract: After analyzing various studies, we can conclude that the elements characterizing an effective school unit are leadership, teachers, and communication among school unit members, the climate of a school unit, school culture, the logistical infrastructure, the school's relationship with the local community, and the administrative system of the educational institution. The ultimate goal of this research is to detect the current organization and administration situation of secondary education units. In particular, to examine the concept of education, the school role and the concept of effective school, to identify the existing model of administration of the educational system, the organization and administration models of the school unit in which the respondents work, and furthermore the school culture level. The method adopted for the study is the classified cluster sampling method. According to this method, clusters are initially defined, which in this case are Secondary School Units. The clusters are then classified according to their characteristics, which in this case was the geographical feature: they all belonged to the North Aegean Region. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE «19o NAVIGATOR 2019 - THE SHIPPING DECISION MAKERS FORUM» Athens, 10th, December 2019 The 19th NAVIGATOR 2019 - THE SHIPPING DECISION MAKERS FORUM was organized by NAVIGATOR SHIPPING CONSULTANTS with great success on Friday, November 29, 2019 at the "Lighthouse" of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center. The response to the call to the maritime industry to #bepartofthechange was impressive with the participation of more than 600 including high- ranking stakeholders from the entire shipping spectrum – shipping executives, representatives from maritime organizations, journalists, Embassies, academics and students from Universities as well as from the Merchant Marine Academies of Oinousses, Hydra and Aspropyrgos. Danae Bezantakou, CEO of NAVIGATOR welcomed the participants underlining that this Navigator Forum 2019 is the result of discussions and meetings which took place on a monthly basis in collaboration with the Advisory Board, composed by most of sponsors and speakers of the Forum. The Advisory Board is the forerunner of a shipping think tank that pledged to be institutionalized with NAVIGATOR ASSEMBLY, which firstly was addressed to Shipowners of 1-15 ships. The results of the 8 discussion topics related to NEW REGULATIONS, SMART SHIPPING, HUMAN ELEMENT, LEGAL & INSURANCE, GREEN FINANCING, PORT STATE CONTROL, COMMERCIAL, SUPPLY CHAIN were presented during the forum by the respective moderators. The President of NAVIGATOR, Capt. Dimitris Bezantakos, was referred to the volatile period of the global shipping and economy, which creates a puzzle of strange social phenomena, such as terrorism and malicious acts on ships and installations, leading to a trampoline of oil prices. He also referred to the new regulations the problems that their implementation will cause and the major changes that are taking place in the tug- boats' market in Europe and beyond. -

Adoption Des Déclarations Rétrospectives De Valeur Universelle Exceptionnelle

Patrimoine mondial 40 COM WHC/16/40.COM/8E.Rev Paris, 10 juin 2016 Original: anglais / français ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L’ÉDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Quarantième session Istanbul, Turquie 10 – 20 juillet 2016 Point 8 de l’ordre du jour provisoire : Etablissement de la Liste du patrimoine mondial et de la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril. 8E: Adoption des Déclarations rétrospectives de valeur universelle exceptionnelle RESUME Ce document présente un projet de décision concernant l’adoption de 62 Déclarations rétrospectives de valeur universelle exceptionnelle soumises par 18 États parties pour les biens n’ayant pas de Déclaration de valeur universelle exceptionnelle approuvée à l’époque de leur inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial. L’annexe contient le texte intégral des Déclarations rétrospectives de valeur universelle exceptionnelle dans la langue dans laquelle elles ont été soumises au Secrétariat. Projet de décision : 40 COM 8E, voir Point II. Ce document annule et remplace le précédent I. HISTORIQUE 1. La Déclaration de valeur universelle exceptionnelle est un élément essentiel, requis pour l’inscription d’un bien sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial, qui a été introduit dans les Orientations devant guider la mise en oeuvre de la Convention du patrimoine mondial en 2005. Tous les biens inscrits depuis 2007 présentent une telle Déclaration. 2. En 2007, le Comité du patrimoine mondial, dans sa décision 31 COM 11D.1, a demandé que les Déclarations de valeur universelle exceptionnelle soient rétrospectivement élaborées et approuvées pour tous les biens du patrimoine mondial inscrits entre 1978 et 2006. -

Investment Profile of the Chios Island

Island of Chios - Investment Profile September 2016 Contents 1. Profile of the island 2. Island of Chios - Competitive Advantages 3. Investment Opportunities in the island 4. Investment Incentives 1. Profile of the island 2. Island of Chios - Competitive Advantages 3. Investment Opportunities in the island 4. Investment Incentives The island of Chios: Οverview Chios is one of the largest islands of the North East Aegean and the fifth largest in Greece, with a coastline of 213 km. It is very close to Asia Minor and lies opposite the Erythraia peninsula. It is known as one of the most likely birthplaces of the ancient mathematicians Hippocrates and Enopides. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic and its nickname is ”The mastic island”. The Regional Unit of Chios includes the islands of Chios, Psara, Antipsara and Oinousses and is divided into three municipalities: Chios, Psara and Oinouses. ➢ Area of 842.5 km² ➢ 5th largest of the Greek islands ➢Permanent population: ➢52.574 inhabitants (census 2011) including Oinousses and Psara ➢51.390 inhabitants (only Chios) Quick facts The island of Chios is a unique destination with: Cultural and natural sites • Important cultural heritage and several historical monuments • Rich natural environment of a unique diversity Archaeological sites: 5 • Rich agricultural land and production expertise in agriculture and Museums: 9 livestock production (mastic, olives, citrus fruits etc) Natura 2000 regions: 2 • RES capacity (solar, wind, hydro) Beaches: 45 • Great concentration in fisheries and aquaculture Source: http://www.chios.gr • Satisfactory infrastructure of transport networks (1 airport, 2 ports and road network) • Great history, culture and tradition in mercantile maritime, with hundreds of seafarers and ship owners Transport infrastructure Chios is served by one airport and two ports (Chios-central port and Mesta-port) and a satisfactory public road network. -

LESVOS LIMNOS AGIOS EFSTRATIOS CHIOS OINOUSSES PSARA SAMOS IKARIA FOURNOI 2 9 Verschiedene Welten

LESVOS LIMNOS AGIOS EFSTRATIOS CHIOS OINOUSSES PSARA SAMOS IKARIA FOURNOI 2 9 verschiedene Welten... Entdecken Sie sie!! REGIONALVERWALTUNG DER NORDÄGÄIS 1 Kountourioti Str., 81 100 Mytilini Tel.: 0030 22513 52100 Fax: 0030 22510 46652 www.pvaigaiou.gov.gr TOURISMUSBEHÖRDE Tel.: 0030 22510 47437 Fax: 0030 22510 47487 e-mail: [email protected] © REGIONALVERWALTUNG DER NORDÄGÄIS FOTOGRAFEN: Giorgos Depollas, Giorgos Detsis, Pantelis Thomaidis, Christos Kazolis, Giorgos Kakitsis, Andreas Karagiorgis, Giorgos Malakos, Christos Malahias, Viron Manikakis, Giorgos Misetzis, Klairi Moustafelou, Dimitris Pazaitis, Pantelis Pravlis, Giannis Saliaris, Kostas Stamatellis, Petros Tsakmakis, Giorgos Filios, Tolis Flioukas, Dimitris Fotiou, Tzeli Hatzidimitriou, Nikos Chatziiakovou 3 Inseln der Nordägäis Mehr als zweitausend kleine und große Inseln schmücken wie auf dem Meer schwimmende wertvolle Seerosen den Archipel Griechenlands. Im Nordostteil der Ägäis dominieren die Inseln: Limnos, Ai Stratis, Lesvos, Psara, Chios, Oinousses, Samos, Ikaria und Fournoi. Es sind besondere Inseln, auf denen die Geschichte eindringlich ihre Spuren hinterlassen hat, lebende Organismen eines vielseitigen kulturellen Wirkens, das sich in Volksfesten und Traditionen, darstellender und bildender Kunst, Produkten und Praktiken sowie in der Architektur des strukturierten Raumes ausdrückt. Die eigentümliche natürliche Umgebung und die wechselnden Landschaften heben die Inseln der Nordägäis hervor und führen den Besucher auf Entdeckungs- und Erholungspfade. Feuchtbiotope -

The Chios, Greece Earthquake of 23 July 1949: Seismological Reassessment and Tsunami Investigations

Pure Appl. Geophys. 177 (2020), 1295–1313 Ó 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02410-1 Pure and Applied Geophysics The Chios, Greece Earthquake of 23 July 1949: Seismological Reassessment and Tsunami Investigations 1 2 3,4 1 5 NIKOLAOS S. MELIS, EMILE A. OKAL, COSTAS E. SYNOLAKIS, IOANNIS S. KALOGERAS, and UTKU KAˆ NOG˘ LU Abstract—We present a modern seismological reassessment of reported by various agencies, but not included in the Chios earthquake of 23 July 1949, one of the largest in the Gutenberg and Richter’s (1954) generally authorita- Central Aegean Sea. We relocate the event to the basin separating Chios and Lesvos, and confirm a normal faulting mechanism tive catalog. This magnitude makes it the second generally comparable to that of the recent Lesvos earthquake largest instrumentally recorded historical earthquake located at the Northern end of that basin. The seismic moment 26 in the Central Aegean Sea after the 1956 Amorgos obtained from mantle surface waves, M0 ¼ 7 Â 10 dyn cm, makes it second only to the 1956 Amorgos earthquake. We compile event (Okal et al. 2009), a region broadly defined as all available macroseismic data, and infer a preference for a rupture limited to the South by the Cretan–Rhodos subduc- along the NNW-dipping plane. A field survey carried out in 2015 tion arc and to the north by the western extension of collected memories of the 1949 earthquake and of its small tsunami from surviving witnesses, both on Chios Island and nearby the Northern Anatolian Fault system. -

Obesity in Mediterranean Islands

Obesity in Mediterranean Islands Supervisor: Triantafyllos Pliakas Candidate number: 108693 Word count: 9700 Project length: Standard Submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MSc in Public Health (Health Promotion) September 2015 i CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background on Obesity ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Negative Impact of Obesity ..................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 The Physical and Psychological ....................................................................... 1 1.2.2 Economic Burden ............................................................................................ 2 1.3 Obesity in Mediterranean Islands ............................................................................ 2 1.3.1 Obesity in Europe and the Mediterranean region ............................................. 2 1.3.2 Obesogenic Islands ......................................................................................... 3 1.4 Rationale ................................................................................................................ 3 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................. 4 3 METHODS .................................................................................................................... -

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2017, 71-94 Sustainable Local

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2017, 71-94 Sustainable local development on Aegean Islands: a meta-analysis of the literature Sofia Karampela University of the Aegean, Mytilini, Greece [email protected] Charoula Papazoglou University of the Aegean, Mytilini, Greece [email protected] Thanasis Kizos University of the Aegean, Mytilini, Greece [email protected] and Ioannis Spilanis University of the Aegean, Mytilini, Greece [email protected] ABSTRACT: Sustainable local development is central to debates on socioeconomic and environmental change. Although the meaning of sustainable local development is disputed, the concept is frequently applied to island cases. Studies have recently been made of many local development initiatives in different contexts, with various methods and results. These experiences can provide valuable input on planning, managing, and evaluating sustainable local development on islands. This paper provides a literature review of positive and negative examples of sustainable local development for the Aegean Islands, Greece. Out of an initial 1,562 papers, 80 papers made the final selection based on theme, empirical approach, and recency. The results demonstrate a wide thematic variety in research topics, with tourism, agriculture, and energy being the most frequent themes, while integrated frameworks are largely absent. The literature includes a wide range of methods, from quantitative approaches with indicators and indexes to qualitative assessments, which blurs overall assessments in many instances. Keywords: Aegean islands, economy, environment, sustainable local development, meta-analysis https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.6 © 2017 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. 1. Introduction Sustainability and sustainable development are notions that are widely used today in areas of research, policies, monitoring, and planning (Spilanis et al., 2009). -

NAUTICAL the Sea Is Nearly All About Greece

NAUTICAL www.visitgreece.gr The sea is nearly all about Greece. An aquatic heaven, in abundance. So, sail the deep blue sea and explore the teeming with life. Seawaters wash the continental part 3,000 islands of the Greek archipelago and the coastline NAUTICAL_2 Sail the from the East, the South and the West, creating a wealth that extends for more than 20,000 km. Live your dream! of ever-changing images, completing the greater picture, showing the harmony and sheer beauty of it all. Follow this travelogue and sail the Greek seas, discover mythological figures, legendary heroes and ordinary men. Visiting a place is not just about seeing it; it is mostly about experiencing the way of life on it. Geographical View the coastline and part of the inland from a different dream information, even the most detailed data, cannot but fail perspective. Acquaint yourself with the unique character to describe the place’s true character. This brochure aims and amazing topography of the various groups of islands. only at becoming an incentive for future tourists, as the Feel the vigour of nature! true challenge is about discovery and experience. Our sea voyage will start from the Ionian Sea and When one thinks of Greek seas, water sports are most likely the western Greek shoreline, continue all along the to spring to mind. Greece is the ideal place for enjoying Pelopponesian coast, Attica and the Argo-Saronic Gulf; them as there are modern facilities, experienced teachers we will sail through the Cycladic islands, then on to the and well-organised schools for a wide variety of activities such as water-skiing, windsurfing, kite surfing, scuba Sporades Islands and the Northern Aegean Islands, then diving, sport fishing or ringo and banana riding. -

Rapid Assessment of the Refugee Crisis in the Aegean Islands During August and September 2015

Second Draft Report ASSESMENT Migration Aegean Islands Rapid Assessment of the Refugee Crisis in the Aegean Islands during August and September 2015 SolidarityNow Athens, 25 November 2015 Page 1 of 30 Second Draft Report ASSESMENT Migration Aegean Islands Foreword Within the framework of the EEAGR08.02 Project and according to the Project’s contract, a fund for bilateral relations was set aside to fund activities that encourage cooperation between actors in Greece and the Donor states or with Intergovernmental organizations. In view of utilizing this fund in order to enhance the bilateral relations between Greece and Norway while also addressing the urgent issue of augmenting refugee and migration flows, SN proposed to the Fund Operator and the Project’s donors to cooperate with selected Norwegian NGOs within the framework of the emergency crisis that is ongoing in Greece since spring 2015. This –honestly- didn’t seem as the most “mainstream” suggestion for the cause. As the main means to achieve the objective. Moreover, what was broadly discussed and also partially documented up to the time the idea of a joint assessment was finally shaped and proposed was a basic exchange project between Greek and Norwegian NGO partners including a number of visits and events to touch base and establish initial lines of communication. Still, the ground developments in Greece couldn’t leave Solidarity Now’s plans unaltered or our mind and hearts unchanged to the drama unfolding. Knowing that one of the main objectives of our mutual effort with EEA Grants was to ensure access to a comprehensive package of services to the mostly need and marginalized populations, we started working on a contingency plan that would combine addressing simultaneously People on the Move as well as Greek citizens’ needs while adjusting to a new reality, characterized by significant refugee and migrant flows as well as by the deepening results of a national socioeconomic crisis. -

LESVOS LIMNOS AGIOS EFSTRATIOS CHIOS OINOUSSES PSARA SAMOS IKARIA FOURNOI 2 3 9 Worlds

LESVOS LIMNOS AGIOS EFSTRATIOS CHIOS OINOUSSES PSARA SAMOS IKARIA FOURNOI 2 3 9 worlds... explore them all! NORTH AEGEAN REGION 1 Kountourioti Str., 81 100 Mytilini Tel.: 0030 22513 52100 Fax: 0030 22510 46652 www.pvaigaiou.gov.gr DIRECTORATE OF TOURISM Tel.: 0030 22510 47437 Fax: 0030 22510 47487 e-mail: [email protected] © NORTH AEGEAN REGION Islands of the North Aegean More than two thousand small and large islands adorn Greece, making up our country’s archipelago, like invalu- able lily pads resting on the sea. The northeast edge of the Aegean is dominated by the islands of Limnos, Agios Efstratios, Lesvos, Psara, Chios, Oinousses, Samos, Ikaria and Fournoi. Singular islands, with history’s marks still easily discernible, they are living organisms of multifaceted cultural activity and expression, with popular events and traditions, performing and visual art forms, local products and practices, and architectural styles. The unique natural environment and variety of scenery make the islands of the N. Aegean stand out and lead visitors to trails for exploration and recreation. Wetlands with rare flora and fauna, salt marshes, waterfalls, dense forests of pine, walnut, oak, olive groves, mastic trees are just a few of the things to be enjoyed on the islands. The islands of the North Aegean, so very different from one another, like the pebbles on a beach, have something that brings them together and yet makes them stand out. They have managed to maintain their local culture and natural environ- ment, offering visitors unique images, flavours and scents of times past. “Anemoessa” Limnos of the rocks and Poliochne - the most ancient organized city in Europe – crowned with its vineyards and its islands, almost untouched by time. -

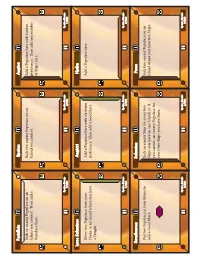

Print and Play

Psytalleia Spetses Aegina Sack an enemy Populace on an Sack two enemy Populace on an Add a Populace here with timber Island you control. Then add a Island you control. preference. Then add any number Populace there. of Ships here. Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze 7/220 4/220 1/220 Leros Salaminos Angistri Hydra Move two Populace from your Add a Populace here with electrum Add a Populace here. Home to an Island where you have preference. Then add a Good here. a Temple. Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze 8/220 5/220 2/220 Revythoussa Salamina Poros Pay two Populace at your Home to Sack an enemy Ship for every two Sack two enemy Populace on an add a Good there. Ships you have on one Island, or if Island where you have two Ships. you cannot, an enemy Populace for every two Ships you have there. Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze 9/220 6/220 3/220 Plateia Spetsopoula Moni Aiginas Sack an enemy Populace on every Add a Populace here. Then pay Add a Populace here with bronze Island where you have a Populace a Good here to add a Populace at preference. Then add another except your Home. each Island with a Good. Populace here. Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze Sparta - Bronze 16/220 13/220 10/220 Bisti Petrokaravo Dokos Move one or more of your Populace Move three Populace from Home to Sack an enemy Populace on each on one Ship to any other Island. an Island where you have a Temple Island where you have a Ship.