Trade Marks Inter Partes Decision O/066/20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terms and Condition of Online Shopping At

TERMS AND CONDITION OF ONLINE SHOPPING AT WWW.SACOORBROTHERS.COM These terms and conditions (“T&C”) are a legally binding agreement and are part of the terms and conditions that govern the acquisition from SACNET SA, a company incorporated under Portuguese law and registered at the Cascais Companies Registration office under the tax number. 509791484, with registered office at Talaíde Park, Estrada Octávio Pato, nº 177, Edif. A, A3, 2785-783 S. Domingos de Rana, (“Sacoor”) by any Sacoor Brothers customer (“Customer”) of products through the website www.sacoorbrothers.com/en (“Website”). Customers may access these terms and conditions in PDF format for download and reproduction. The Website is managed by Sacoor. Customers must ensure that they have carefully read the information in these T&C, bearing in mind that these are directly applicable to any orders made on the Website. By accepting the T&C, Customers are declaring that they have the necessary capacity for signing a Contract, namely that they are aged over 18, and that they have understood and accept all of their provisions. If a Customer is a company, these T&C shall be applicable with the necessary changes. 1. ORDERS AND PAYMENT At the moment, online ordering and delivery of Sacoor products is only possible in the following countries: Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Byelorussia, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malta, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, Vatican City, the United Kingdom. -

Portugal a Country-Brand in Fashion Interview

BUSINESS,ECONOMY,MARKETING AND LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE PORTUGAL A COUNTRY-BRAND IN FASHION REVIEW INTERVIEW WINTER 2017 • YEAR XIV • 0,01 EUROS • QUARTERLY • DIRECTOR SOFIA ARNAUD • DIRECTOR • QUARTERLY YEAR XIV • 0,01 EUROS WINTER 2017 • CATALONIA: FERNANDO FARIA THE HISTORY OF A BUSINESS DE OLIVEIRA COUNTRY DENIED RONALDO PLANET ON THE WAY TO MATURITY WITH THE SUPPORT SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY OF OUR COLLEAGUES BUSINESS FROM BRAZIL AND UNICEF: AN INSTITUTION ON THE FRONT LINE MOZAMBIQUE AND OF WITH MORE THAN 70 YEARS OF THE DIGITAL OUR PARTNERS FROM OF HISTORY SPAIN AND COLOMBIA TRANSFORMATION DIRECTOR CONTENTS ART DIRECTOR Hugo de Jesus WRITING Carlos Renato Teixeira, Maria João de Perestrello, João Bérnard Garcia e Miguel Morgado COLLABORATORS IN THIS EDITION António Cunha Vaz, Daniel Feged, David Seromenho, Paget Langford-Holt e Tiago Antunes TRANSLATION Outernational ADVERTISING Tel.:+351 21 012 06 00 PRINTER OWNERSHIP Cunha Vaz & Associados – Consultores em Comunicação, SA EDITORIAL OFFICE Av. dos Combatentes, n.º 43, 12.º 1600-042 Lisboa CRC LISBON 13538-01 ERC REGISTER 124 353 LEGAL DEPOSIT 4 EDITORIAL 28 BUSINESS 42 BUSINESS 320943/10 6 NEWS Ronaldo Planet CIRCULATION News from the world 34 BUSINESS 44 BUSINESS 2000 Copies 8 CV&A CTT: On the front line of the C V & A C O R P O R A T I V E MAGAZINE The CV&A partners in Brazil, digital transformation Portuguese tables Spain and Colombia 36 BUSINESS 46 SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 14 BANK Talking with Nuno Barra, UNICEF: The organization from Interview to Fernando Faria Director of Vista Alegre-Atlantis -

Majid Al Futtaim Reports Strong 2016 Growth Whilst Continuing Expansion Into New Territories

PRESS RELEASE: Majid Al Futtaim reports strong 2016 growth whilst continuing expansion into new territories Key Highlights: Note: The following information is a trading statement based on unaudited management accounts for Full Year ended 31 December 2016. • Overall group revenue up 9% year-on-year to AED 29.9 billion for full year 2016 • EBITDA up 8% at AED 4.1 billion • Commenced construction of the 103,000 sqm City Centre Almaza, Cairo and Aloft Hotel, City Centre Deira and began expansions at City Centre Ajman and City Centre Sharjah • Successfully opened My City Centre Al Barsha • Expanded the Carrefour network with 10 new supermarkets and 10 new hypermarkets, including the company’s first hypermarket in Africa in Kenya • Increased VOX Cinemas footprint in Oman and established joint-ventures in Bahrain, bringing its total number of screens to 242 and making it the largest cinema operator in the Middle East and North Africa region • Unveiled first outdoor VOX Cinemas concept in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, and refurbished VOX Cinemas at City Centre Deira • Opened four new Magic Planet entertainment centres and three new LEGO stores • City Centre Me’aisem awarded Green Commercial Building of the Year by Emirates GBC Awards Programme • Received 18 retail awards from the Middle East Council for Shopping Centres • Ski Dubai awarded 2016 World Ski Award for the World’s Best Indoor Ski Resort • Launched Tomouhi, the company’s new Graduate Management Development Programme • Increased headcount to 34,000 employees and 104 nationalities • BBB -

The Edge CC -- Brisco

PAVILION KUALA LUMPUR ` Pavilion Kuala Lumpur is an award-winning, world-class mixed-use urban development located in the heart of Bukit Bintang, the shopping paradise of Malaysia. Opened to visitors on 20 September 2007, Pavilion Kuala Lumpur blends the best of the international and local retail world and is positioned as the ‘Defining authority in fashion, food and urban leisure’. A NATIONAL LANDMARK PAVILION CRYSTAL FOUNTAIN The essence of this fountain is a reflection of our Prime Minister’s “1 Malaysia” vision. The fountain features the Bloom of Hibiscus, the national flower of Malaysia, a symbol of opulence, passion and progression. The three bowls represent Malaysia’s multiracial culture living harmoniously in unity and ascending to signify the growing aspirations of the people. Designer Pavilion KL in collaboration with Liuligongfang The crystal bowls were crafted in Shanghai, China Malaysia Book of Record Tallest Liuli Crystal Fountain in Malaysia 3.6m in height 6m in width PROJECT FACTS Location Bukit Bintang, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Owner MTrustee Berhad for Pavilion REIT Description Pavilion Kuala Lumpur is a world-class mixed-use urban development, comprising a 7-storey premier shopping mall, 2 blocks of Pavilion Residences, Pavilion Tower office block and the upcoming 5-star Royale Pavilion Hotel. Land Area 12.6 acres Nett Lettable Area 1.37 million square feet Gross Built-up Area 2.2 million square feet Number of Retail Floors Seven (7) Number of Stores 698 Precincts Eight (8) - Gourmet Emporium, Level 1 - Centre Court, Level -

Annual Report 2012

PAVILION REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUST • ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Pavilion REIT Management Sdn. Bhd. (Company Number : 939490-H) Level 10, Pavilion Kuala Lumpur, 168, Jalan Bukit Bintang, 55100 Kuala Lumpur T : +603 2118 8888 F : +603 2118 8889 E : [email protected] W : www.pavilion-reit.com Annual Report 2012 VISION, MISSION AND INVESTMENT STRATEGIES Pavilion REIT was established on 13 October 2011 and listed on Main Market of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad on 7 December 2011 with the principal investment policy of investing, directly and indirectly, in a diversified portfolio of income producing real estate used solely or predominantly for retail purposes (including mixed-use developments with a retail component) in Malaysia and other countries within the Asia-Pacific region as well as real estate related assets. VISION To be the leading and most sought after REIT in Malaysia. MISSION To provide unitholders with regular and stable distributions as well as to achieve long term growth in net asset value per unit, while maintaining an appropriate capital structure. STRATEGIES The Manager intends to achieve the vision and mission of Pavilion REIT through the following strategies: (a) Actively pursuing acquisition opportunities in accordance with the authorised investments of Pavilion REIT – acquire yield accretive income-producing properties – explore repositioning opportunities (b) Pursuing an efficient capital management strategy – diversify sources of debt funding – maintaining a reasonable level of debt service capability – securing -

Softlogic Holdings PLC Annual Report 2019/20 CONTENTS

Softlogic Holdings PLC Annual Report 2019/20 CONTENTS OVERVIEW About This Report 1 Financial Highlights 2 Non-Financial Highlights 3 About The Group 4 Our Businesses 6 Year At A Glance 8 LEADERSHIP FINANCIAL & GOVERNANCE STATEMENTS Chairman’s Message 10 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 56 Board of Directors 14 Independent Auditors’ Report 57 Sector Heads 18 Income Statement 62 Functional Heads 20 Statement of Comprehensive Income 63 Corporate Governance Report 22 Statement of Financial Position 64 Statement of Changes In Equity 66 2 5 Statement of Cash Flow 68 Notes to the Financial Statements 70 OPERATIONAL & SUPPLEMENTARY FINANCIAL REVIEW INFORMATION Overview of Economy 28 Shareholder Information 176 Risk & Uncertainty 29 Corporate Directory 178 Financial Review 32 Notice of Meeting 182 Form of Proxy 183 3 6 Corporate Information IBC MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS Retail 36 Healthcare Services 38 Financial Services 40 Leisure And Property 42 Automobiles 44 4 Information Technology & Others 46 Committee Reports Annual Report of the Board of Directors on the Affairs of the Company 48 Board Audit Committee Report 51 Report of The Related Party Transactions Review Committee 52 HR & Remuneration Committee Report 53 1 ABOUT THIS REPORT This Annual Report covers the operations of Softlogic Holdings PLC and its Group companies for the period from 1st April 2019 to 31st March 2020. Given the unprecedented financial and operational challenges that prevailed during the year, we have sought to produce a concise report which complies with all relevant statutory requirements while fulfilling the high-level information needs of our stakeholders. The Report includes discussions on the Group’s operating landscape during the year, strategy and performance of business sectors, corporate governance, and risk management practices. -

Traffic Fatalities Drop in Qatar

QATAR | Page 24 SPORT | Page 1 Pep draws fi rst blood INDEX as Man City DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-4, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 MoI lines up cultural REGION 6 BUSINESS 1 – 12 shows for communities’ win derby 18,137.87 10,534.10 45.89 ARAB WORLD 7 CLASSIFIED 6, 7 -342.04 -100.80 -1.73 INTERNATIONAL 8 – 21 SPORTS 1 – 8 Eid celebration -1.85% -0.95% -3.63% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXVII No. 10208 September 11, 2016 Dhul-Hijja 9, 1437 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Shoppers flock to stores In brief Traffi c QATAR | Audience fatalities Emir to receive Eid well-wishers HH the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani will receive well- wishers at Al Wajbah Palace on the first day of Eid al-Adha, the drop Emiri Diwan announced yesterday. Immediately after the Eid prayers until 6:15am, the Emir will receive sheikhs, ministers, the Speaker of the Advisory (Shura) Council, ministries’ undersecretaries, Shura Council members and citizens. in Qatar From 6:15am to 6:30am, heads of diplomatic missions will be Traff ic violations accounted for was QR495 (across various categories). received. From 6:30am to 6:45am, 121,684 in July 2016, up 10.02% on Demographic statistics provided by the Emir will receive the armed June this year the Ministry of Development Planning forces and police off icers as well and Statistics indicated that Qatar’s as directors of departments and raffi c fatalities in Qatar have population reached 2,32mn in July, up national institutions. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Vision Design-Led, Quality and Service-Driven

A Testoni / Abercrombie & Fitch / Adidas / AIA / Aigner / Aldo / Alfa Romeo / All Watches / Anya Hindmarch / ANZ / APM / Apple / ArtScience Museum / Art Stage Singapore / Asahi / Ascott International / Asia Pacific Breweries / Aspial / ATR / Audi / Audio–Technica / Aussino / Balenciaga / Bally / Banana Republic / Bang & Olufsen / Bank of America / Barclays / Base Entertainment / Bausch & Lomb / Bebe / Bell & Ross / Bershka / Billabong / Binny & Smith / Blackberry / Bloomberg / BMW / Boeing / Boncafé / Bonia / Bottega Veneta / Boucheron / Braun Buffel / Bridgestone / British Dispensary / British India / Broadridge / Brooks Brothers / Bruno Magli / Buratti / Burberry / Bvlgari / Calvin Klein / Camel Active / Camus / Canali / Canon / Caran d’Ache / Carl F. Bucherer / Cartier / Celine / Cemax Asia / Central Narcotics Bureau / CGV / Chanel / Changi Airport Group / Charles & Keith / Charles Jourdan / Chaumet / Chevignon / Chevrolet / Christian Dior / Christian Louboutin / Citibank / Clarins / Club Culture / Clubmarc / Coach / CoCo ICHIBANYA / Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf / Cold Wear / Cortina Watch / COS / COSCIA / Cotton On / Credit Suisse / CVTOS / Daim Chrysler / DBS / Debenhams / Delifrance / Desigual / Deutsche Telekom / DFS / Diane von Furstenberg / Dickson Group / DKNY / Doosan Heavy Industries / Dunhill / Economic Development Board / Elecom / Electrolux / Eli Lily / Elle / Embassy of Ireland / Embraer / Emporio Armani / EQ:IQ / Ericsson / Ermenegildo Zegna / Escada / Esprit / Estee Lauder / Etro / Etude House / Eurocosmesi / Eu Yan Sang / -

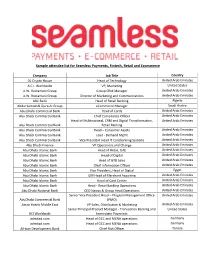

Sample Attendee List for Seamless Payments, Fintech, Retail and Ecommerce

Sample attendee list for Seamless Payments, Fintech, Retail and Ecommerce Company Job Title Country 01 Crypto House Head of Technology United Arab Emirates A.C.I. Worldwide VP, Marketing United States A.W. Rostamani Group Group CRM Manager United Arab Emirates A.W. Rostamani Group Director of Marketing and Communications United Arab Emirates ABC Bank Head of Retail Banking Algeria Abdul Samad Al Qurashi Group eCommerce Manager Saudi Arabia Abu Dhabi Commecial Bank Head of Cards United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank Chief Compliance Officer United Arab Emirates Head of Multinational, CRM and Digital Transformation, United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank Retail Banking Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank Head – Consumer Assets United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank Lead - Demand Mgmt United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank Vice President Head IT Corebanking Systems United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Finance VP Operations and Change United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank Head of Retail, UAE United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank Head of Digital United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank Head of GTB Sales United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank Chief Information Officer United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank Vice President, Head of Digital Egypt Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank GM Head of Merchant Acquiring United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank Head of Card Centre United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank Head - Retail Banking Operations United Arab Emirates Abu Dhabi National Bank CEO Nawat & Group Head -

P7 Northwestern Eastern University in Qatar Will P20 Germany Keeps Have the Opportunity Its Plush While This Summer to Updating for the Further Their Research

Community Community Two students Art Deco from cinema in P7 Northwestern eastern University in Qatar will P20 Germany keeps have the opportunity its plush while this summer to updating for the further their research. modern age. Monday, June 13, 2016 Ramadan 8, 1437 AH DOHA 33°C—42°C TODAY LIFESTYLE/HOROSCOPE 13 PUZZLES 14 & 15 On the Zika trail It has reached 60 countries and territories, but there’s much that COVER STORY the scientists still don’t know about the crippling virus. P4-5 BONDING: Evellyn Mendes Santos, 9, kisses her baby sister, Heloyse, outside of their home in Joao Pessoa, Brazil. Their mother, Maria da Luz Mendes Santos, said it was her “biggest dream” to have two daughters. 2 GULF TIMES Monday, June 13, 2016 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT Love Me Tomorrow GENRE: Comedy, Romance CAST: Piolo Pascual, Coleen Garcia, Dawn Zulueta DIRECTION: Gino M Santos SYNOPSIS: A generational love story about a DJ, a confl icted millennial woman, and a woman who is described to PRAYER TIME be ‘on the verge of renaissance’. They Fajr 3.14am will be caught in a Shorooq (sunrise) 4.43am love triangle that will Zuhr (noon) 11.34am spark thoughts on Asr (afternoon) 2.57pm one-night stands, Maghreb (sunset) 6.28pm May-December Isha (night) 7.58pm aff airs and other aspects of life. Love Me Tomorrow USEFUL NUMBERS is a timely and empowering fi lm that celebrates the enduring power of true love. THEATRES: The Emergency 999 Mall, Royal Plaza Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires -

Retailnext the NEW WAVE of PEOPLE, PRODUCTS & PROCESSES

2019 Post Show Report RetailNEXT THE NEW WAVE OF PEOPLE, PRODUCTS & PROCESSES 14-15 October 2019 Le Méridien Hotel & Conference Centre, Dubai EVENT PARTNERS GOLD PARTNERS CX PARTNER SILVER PARTNERS EXHIBITION KNOWLEDGE DESIGN MEDIA PARTNER PARTNER PARTNER PARTNERS RetailNEXT #MRF2019 THE NEW WAVE OF PEOPLE, PRODUCTS & PROCESSES ABOUT MIDDLE EAST RETAIL FORUM 2019 The Middle East Retail Forum (MRF) is a powerful aggregator of entrepreneurs, leaders, innovators and global retail trends. As the annual flagship knowledge-oriented forum that started eight years ago, MRF facilitates charting out the future of retail’s blueprint in the Middle East and beyond. With the theme “RetailNEXT: The new wave of People, Products & Processes”, MRF 2019 witnessed leaders, visionaries, innovators, change-makers and disruptors share their views on topics ranging from technology to talent, seamless to sustainability…and everything in between. @ME.RetailForum @imagesretailme middleeastretailforum middleeastretailforum middleeastretailforum.com RetailNEXT #MRF2019 THE NEW WAVE OF PEOPLE, PRODUCTS & PROCESSES WHAT THEY SAID 8th EDITION 87+ SPEAKERS 367+ DELEGATES 250+ COMPANIES “Thank you for inviting me to be a part of MRF 2019. “Thanks again for everything It was a pleasure to engage with my colleagues around MRF. It was beneficial in the retail sector. It was a great pleasure to join as I met three retailers with the CEOs Roundtable along so many successful whom I spoke about our colleagues and discuss the ever-changing landscape new brand Samha” of our business” Patrick Dorais, Director of Sales, Al Nassma Chocolate LLC Shames Al Hashemi, Director – Member of Board, Dual Investments Congratulations on an extremely successful conference. -

The Year of Growth the Region’S Dedicated Forum for Retailers, Shopping Centre Owners & Service Providers

JOINTLY ORGANISED BY The Year of Growth The Region’s Dedicated Forum for Retailers, Shopping Centre Owners & Service Providers NOVEMBER 24 - 26, 2013 The Westin Dubai Mina Seyahi, Dubai, UAE www.reconmiddleeast.com PLATINUM SPONSORS ANNUAL SPONSORS GOLD SPONSORS SILVER SPONSORS SUPPORT SPONSOR SUPPORTED AND ENDORSED BY MEDIA PARTNERS RECon Middle East & North Africa 2013 “The Growth of Retail” The preeminent networking and educational conference for the Retailers, Shopping Centre Owners & Service Providers in the Middle East & North Africa. Shopping centres in the Middle East and North Africa are among some of the most vibrant and successful throughout the world. It is clear that what made shopping centres successful in the first place, great brands, good food, and an array of entertainment options, will never go out of fashion. But to make these components work successfully you need to be up on the latest trends and best practices. RECon Middle East & North Africa will take participants on a deep dive to what they need to know now, and in the future, to operate successful shopping centres and to understand our retailers. Conference The three day conference will feature intense pre-conference workshops, conference sessions, and panel discussions by noted industry experts and professionals that know the business inside and out. Just practical information and advice that shopping centre professionals can use to enhance their careers and improve their company’s bottom line. Highlights of some of the topics and discussions this year: • Retail