Índiceen Formato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Andrzej Wajda's Korczak (1990)

Studia Filmoznawcze 39 Wroc³aw 2018 Marek Haltof Northern Michigan University THE CASUALTY OF JEWISH-POLISH POLEMICS: REVISITING ANDRZEJ WAJDA’S KORCZAK (1990) DOI: 10.19195/0860-116X.39.4 Emblematic of Wajda’s later career is Korczak (1990), one of the most important European pictures about the Holocaust. Steven Spielberg1 More interesting than the issue of Wajda’s alleged an- ti-Semitism is the question of Korczak’s martyrdom. East European Jews have suffered a posthumous violation for their supposed passivity in the face of the Nazi death machine. Why then should Korczak be exalted for leading his lambs to the slaughter? It is, I believe, because the fate of the Orphan’s Home hypostatizes the extremity of the Jewish situation — the innocence of the victims, their utter abandonment, their merciless fate. In the face of annihilation, Janusz Korczak’ tenderness is a terrifying reproach. He is the father who did not exist. J. Hoberman2 1 S. Spielberg, “Mr. Steven Spielberg’s Support Letter for Poland’s Andrzej Wajda,” Dialogue & Universalism 2000, no. 9–10, p. 15. 2 J. Hoberman, “Korczak,” Village Voice 1991, no. 6, p. 55. Studia Filmoznawcze, 39, 2018 © for this edition by CNS SF 39.indb 53 2018-07-04 15:37:47 54 | Marek Haltof Andrzej Wajda produced a number of films dealing with the Holocaust and Polish-Jewish relationships.3 His often proclaimed ambition had been to reconcile Poles and Jews.4 The scriptwriter of Korczak, Agnieszka Holland, explained that this was Wajda’s “obsession, the guilt.”5 Given the above, it should come as no surprise that he chose the story of Korczak as his first film after the 1989 return of democracy in Poland. -

The Holocaust in French Film : Nuit Et Brouillard (1955) and Shoah (1986)

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2008 The Holocaust in French film : Nuit et brouillard (1955) and Shoah (1986) Erin Brandon San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Brandon, Erin, "The Holocaust in French film : Nuit et brouillard (1955) and Shoah (1986)" (2008). Master's Theses. 3586. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.y3vc-6k7d https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3586 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOLOCAUST IN FRENCH FILM: NUITETBROUILLARD (1955) and SHOAH (1986) A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Erin Brandon August 2008 UMI Number: 1459690 Copyright 2008 by Brandon, Erin All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 1459690 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. -

Of Gods and Men

A Sony Pictures Classics Release Armada Films and Why Not Productions present OF GODS AND MEN A film by Xavier Beauvois Starring Lambert Wilson and Michael Lonsdale France's official selection for the 83rd Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film 2010 Official Selections: Toronto International Film Festival | Telluride Film Festival | New York Film Festival Nominee: 2010 European Film Award for Best Film Nominee: 2010 Carlo di Palma European Cinematographer, European Film Award Winner: Grand Prix; Ecumenical Jury Prize - 2010Cannes Film Festival Winner: Best Foreign Language Film, 2010 National Board of Review Winner: FIPRESCI Award for Best Foreign Language Film of the Year, 2011 Palm Springs International Film Festival www.ofgodsandmenmovie.com Release Date (NY/LA): 02/25/2011 | TRT: 120 min MPAA: Rated PG-13 | Language: French East Coast Publicist West Coast Publicist Distributor Sophie Gluck & Associates Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Sophie Gluck Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 124 West 79th St. Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10024 110 S. Fairfax Ave., Ste 310 550 Madison Avenue Phone (212) 595-2432 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] Phone (323) 634-7001 Phone (212) 833-8833 Fax (323) 634-7030 Fax (212) 833-8844 SYNOPSIS Eight French Christian monks live in harmony with their Muslim brothers in a monastery perched in the mountains of North Africa in the 1990s. When a crew of foreign workers is massacred by an Islamic fundamentalist group, fear sweeps though the region. The army offers them protection, but the monks refuse. Should they leave? Despite the growing menace in their midst, they slowly realize that they have no choice but to stay… come what may. -

Jewish Experience on Film an American Overview

Jewish Experience on Film An American Overview by JOEL ROSENBERG ± OR ONE FAMILIAR WITH THE long history of Jewish sacred texts, it is fair to characterize film as the quintessential profane text. Being tied as it is to the life of industrial science and production, it is the first truly posttraditional art medium — a creature of gears and bolts, of lenses and transparencies, of drives and brakes and projected light, a creature whose life substance is spreadshot onto a vast ocean of screen to display another kind of life entirely: the images of human beings; stories; purported history; myth; philosophy; social conflict; politics; love; war; belief. Movies seem to take place in a domain between matter and spirit, but are, in a sense, dependent on both. Like the Golem — the artificial anthropoid of Jewish folklore, a creature always yearning to rise or reach out beyond its own materiality — film is a machine truly made in the human image: a late-born child of human culture that manifests an inherently stubborn and rebellious nature. It is a being that has suffered, as it were, all the neuroses of its mostly 20th-century rise and flourishing and has shared in all the century's treach- eries. It is in this context above all that we must consider the problematic subject of Jewish experience on film. In academic research, the field of film studies has now blossomed into a richly elaborate body of criticism and theory, although its reigning schools of thought — at present, heavily influenced by Marxism, Lacanian psycho- analysis, and various flavors of deconstruction — have often preferred the fashionable habit of reasoning by decree in place of genuine observation and analysis. -

Bibliographie Der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020)

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff; Ludger Kaczmarek Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014– 2020) 2020 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14981 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Kaczmarek, Ludger: Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020). Westerkappeln: DerWulff.de 2020 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 197). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14981. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0197_20.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 197, 2020: Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020). Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek. ISSN 2366-6404. URL: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0197_20.pdf. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Letzte Änderung: 19.10.2020. Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020) Zusammengestell !on "ans #$ %ul& und 'udger (aczmarek Mit der folgenden Bibliographie stellen wir unseren Leser_innen die zweite Fortschrei- bung der „Bibliographie der Filmmusik“ vor die wir !""# in Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere $#% !""#& 'rgänzung )* +,% !"+-. begr/ndet haben. 1owohl dieser s2noptische 3berblick wie auch diverse Bibliographien und Filmographien zu 1pezialproblemen der Filmmusikforschung zeigen, wie zentral das Feld inzwischen als 4eildisziplin der Musik- wissenscha5 am 6ande der Medienwissenschaft mit 3bergängen in ein eigenes Feld der Sound Studies geworden ist. -

The Shoah on Screen – Representing Crimes Against Humanity Big Screen, Film-Makers Generally Have to Address the Key Question of Realism

Mémoi In attempting to portray the Holocaust and crimes against humanity on the The Shoah on screen – representing crimes against humanity big screen, film-makers generally have to address the key question of realism. This is both an ethical and an artistic issue. The full range of approaches has emember been adopted, covering documentaries and fiction, historical reconstructions such as Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, depicting reality in all its details, and more symbolic films such as Roberto Benigni’s Life is beautiful. Some films have been very controversial, and it is important to understand why. Is cinema the best way of informing the younger generations about what moire took place, or should this perhaps be left, for example, to CD-Roms, videos Memoi or archive collections? What is the difference between these and the cinema as an art form? Is it possible to inform and appeal to the emotions without being explicit? Is emotion itself, though often very intense, not ambivalent? These are the questions addressed by this book which sets out to show that the cinema, a major art form today, cannot merely depict the horrors of concentration camps but must also nurture greater sensitivity among increas- Mémoire ingly younger audiences, inured by the many images of violence conveyed in the media. ireRemem moireRem The Shoah on screen – www.coe.int Representing crimes The Council of Europe has 47 member states, covering virtually the entire continent of Europe. It seeks to develop common democratic and legal princi- against humanity ples based on the European Convention on Human Rights and other reference texts on the protection of individuals. -

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA CELEBRATES THE 75th ANNIVERSARY OF THE NEW YORK FILM CRITICS CIRCLE BY INVITING MEMBERS TO SELECT FILM FOR 12-WEEK EXHIBIITON Critical Favorites: The New York Film Critics Circle at 75 July 3—September 25, 2009 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters & The Celeste Bartos Theater NEW YORK, June 19, 2009 —The Museum of Modern Art celebrates The New York Film Critics Circle’s (NYFCC) 75th anniversary with a 12-week series of award-winning films, from July 3 to September 25, 2009, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters. As the nation‘s oldest and most prestigious association of film critics, the NYFCC honors excellence in cinema worldwide, giving annual awards to the ―best‖ films in various categories that have all opened in New York. To mark the group‘s milestone anniversary, each member of the organization was asked to choose one notable film from MoMA‘s collection that was a recipient of a NYFCC award to be part of the exhibition. Some screenings will be introduced by the contributing film critics. Critical Favorites: The New York Film Critics Circle at 75 is organized by Laurence Kardish, Senior Curator, Department of Film, in collaboration with The New York Film Critics Circle and 2009 Chairman Armond White. High-resolution images are available at www.moma.org/press. No. 58 Press Contacts: Emily Lowe, Rubenstein, (212) 843-8011, [email protected] Tessa Kelley, Rubenstein, (212) 843-9355, [email protected] Margaret Doyle, MoMA, (212) 408-6400, [email protected] Film Admission: $10 adults; $8 seniors, 65 years and over with I.D. -

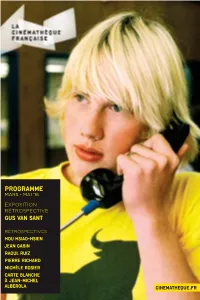

Prog-Web.Pdf

Programme Programme MARS - MAI ‘16 EXPOSITION MARS - MAI 2016 RÉTROSPECTIVE GUS VAN SANT RÉTROSPECTIVES HOU HSIAO-HSIEN Jean gabin Raoul ruiz Pierre richard MichÈle rosier Carte blanche à jean-michel alberola cinematheque.fr La Cinematheque-Parution MDE-012016 19/01/16 15:12 Page1 www.maisondesetatsunis.com POUR Vos voyages à PORTLAND La Maison des Etats-Unis ! Love Portland - 1670 €* Séjour de 7 j. / 5 n. Vols internationaux, hôtel*** Partez assisté d’une équipe de spécialistes qui fera de votre voyage un moment inoubliable. Retrouvez l’ensemble de nos offres www.maisondesetatsunis.com 3, rue Cassette Paris 6ème Tél. 01 53 63 13 43 [email protected] Du lundi au samedi de 10h à 19h. Prix à partir de, soumis à conditions Copyright Torsten Kjellstrand www.travelportland.com Gerry ÉDITORIAL Après Martin Scorsese, c’est à Gus Van Sant que la Cinémathèque française consacre une grande exposition et une rétrospective intégrale. Nourri de modernité euro- péenne, figure du cinéma américain indépendant dans les années 90, à l’instar d’un Jim Jarmush pour la décennie précédente, le cinéaste de Portland, Oregon est un authentique plasticien. Nous sommes heureux de montrer pour la première fois en France ses travaux de photographe et de peintre, et d’établir ainsi des correspon- dances avec ses films. Grand inventeur de dispositifs cinématographiques Elephant( , pour citer le plus connu de ses théorèmes), Gus Van Sant est aussi avide d’expériences commerciales, menées au cœur même de l’industrie (Prête-à-tout, Psychose, Will Hunting ou À la recherche de Forrester), et pour lesquelles il peut déployer toute sa plasticité d’auteur très américain, à la fois modeste et déterminé. -

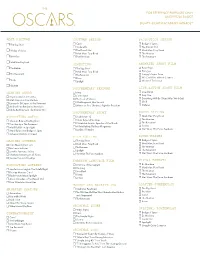

Best Picture Leading Actor Supporting Actor Leading

FOR REFERENCE PURPOSES ONLY UNOFFICIAL BALLOT EIGHTY–EIGHTH ACADEMY AWARDS ® BEST PICTURE COSTUME DESIGN PRODUCTION DESIGN ☐ The Big Short ☐ Carol ☐ Bridge of Spies ☐ Cinderella ☐ The Danish Girl ☐ Bridge of Spies ☐ The Danish Girl ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ The Martian ☐ Brooklyn ☐ The Revenant ☐ The Revenant ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road DIRECTING ANIMATED SHORT FILM ☐ The Martian ☐ The Big Short ☐ Bear Story ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ Prologue ☐ The Revenant ☐ The Revenant ☐ Sanjay’s Super Team ☐ Room ☐ We Can’t Live without Cosmos Room ☐ ☐ Spotlight ☐ World of Tomorrow ☐ Spotlight DOCUMENTARY FEATURE LIVE ACTION SHORT FILM LEADING ACTOR ☐ Amy ☐ Ave Maria ☐ Day One ☐ Bryan Cranston in Trumbo ☐ Cartel Land ☐ Everything Will Be Okay (Alles Wird Gut) ☐ Matt Damon in The Martian ☐ The Look of Silence ☐ Shok ☐ Leonardo DiCaprio in The Revenant ☐ What Happened, Miss Simone? ☐ Stutterer ☐ Michael Fassbender in Steve Jobs ☐ Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom ☐ Eddie Redmayne in The Danish Girl DOCUMENTARY SHORT SOUND EDITING SUPPORTING ACTOR ☐ Body Team 12 ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ The Martian ☐ Christian Bale in The Big Short ☐ Chau, beyond the Lines Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Shoah ☐ The Revenant ☐ Tom Hardy in The Revenant ☐ A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness ☐ Sicario ☐ Mark Ruffalo in Spotlight ☐ ☐ Star Wars: The Force Awakens ☐ Mark Rylance in Bridge of Spies ☐ Last Day of Freedom ☐ Sylvester Stallone in Creed FILM EDITING SOUND MIXING LEADING ACTRESS ☐ The Big Short ☐ Bridge of Spies ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ -

The 88Th Annual Academy Awards Nominations the Oscars Will Be Presented on Sunday, February 28, 2016, at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles

The 88th annual Academy Awards nominations The Oscars will be presented on Sunday, February 28, 2016, at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles Best Picture: Best Foreign Language Film: q "The Big Short" q "Embrace of the Serpent" (Colombia) q "Bridge of Spies" q "Mustang" (France) q "Brooklyn" q "Son of Saul" (Hungary) q "Mad Max: Fury Road" q "Theeb" (Jordan) q "The Martian" q "A War" (Denmark) q "The Revenant" q "Room" Best Adapted Screenplay: q "Spotlight" q "The Big Short" q "Brooklyn" Best Director: q "Carol" q Adam McKay, "The Big Short" q "The Martian" q George Miller, "Mad Max: Fury Road" q "Room" q Alejandro G. Iñárritu, "The Revenant" q Lenny Abrahamson, "Room" Best Original Screenplay: q Tom McCarthy, "Spotlight" q "Bridge of Spies" q "Ex Machina" Best Actor: q "Inside Out" q Bryan Cranston, "Trumbo" q "Spotlight" q Matt Damon, "The Martian" q "Straight Outta Compton" q Leonardo DiCaprio, "The Revenant" q Michael Fassbender, "Steve Jobs" Best Animated Feature Film q Eddie Redmayne, "The Danish Girl" q "Anomalisa" q "Boy and the World" Best Actress: q "Inside Out" q Cate Blanchett, "Carol" q "Shaun the Sheep Movie" q Brie Larson, "Room" q "When Marnie Was There" q Jennifer Lawrence, "Joy" q Charlotte Rampling, "45 Years" Best Cinematography: q Saoirse Ronan, "Brooklyn" q "Carol" q "The Hateful Eight" Best Supporting Actor: q "Mad Max: Fury Road" q Christian Bale, "The Big Short" q "The Revenant" q Tom Hardy, "The Revenant" q "Sicario" q Mark Ruffalo, "Spotlight" q Mark Rylance, "Bridge of Spies" Best Costume Design: q Sylvester Stallone, -

Nga | Viewing History Through the Filmmaker's Lens

VIEWING HISTORY THROUGH THE FILMMAKER'S LENS Agnieszka Holland, lecture delivered Sunday, December 1, 2013 National Gallery of Art When I was thirteen years old, I became fascinated with ancient Rome. The impulse for that was a highly suggestive Polish TV adaptation of Billy Wilder's The Ides of March. I desperately wanted to enter this intense world, and so I decided that I must have reincarnated many times and that in ancient Rome I had been Brutus, with all his complexity and remorse, only to return in the Renaissance, but not as Michelangelo or Leonardo, but as an unknown friend of the latter (who, by the way, had a mysterious, dangerous relationship with Buonarotti). I even kept diaries as these pretended incarnations of mine. I was also convinced that one of my incarnations lived in occupied Poland during the Second World War, but this seemed to painful to write about. It wasn't until years later that this subject came back to me. I don't really believe in films describing historical events that happened ages ago. The stronger the remoteness, the more arbitrarily a filmmaker has to present it. This engenders a certain risk of falling into the most commonly encountered kind of kitsch: simplification, anachronisms, and overt aestheticization. The easiest step is to imitate the external time indicators (though even this requires intuition, knowledge, and diligence), such as costumes, props, and architectural details. The most difficult task is to discover the sense of inner truth, which makes the story deeply rooted in the historical context but at the same time doesn't make it look like some history manual article. -

Family & Domesticity in the Films of Steven Spielberg

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Why Did I Marry A Sentimentalist?: Family & Domesticity in the Films of Steven Spielberg Emmet Dotan Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Dotan, Emmet, "Why Did I Marry A Sentimentalist?: Family & Domesticity in the Films of Steven Spielberg" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 232. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/232 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Did I Marry A Sentimentalist?: Family & Domesticity in the Films of Steven Spielberg Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Arts of Bard College by Emmet Dotan Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 Acknowledgements I want to thank my advisor, Ed Halter, for pushing me to understand why I love the films that I love. I would also like to thank Natan Dotan for always reminding me why I do what I do.