Thyrotoxic Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Personal Experience and Case Collection from the Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

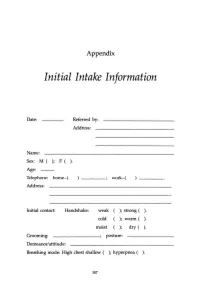

Initial Intake Information

Appendix Initial Intake Information Date: Referred by: Address: Name: Sex: M ( ); F ( ). Age: Telephone: home-( work-( Address: Initial contact: Handshake: weak ); strong ( ). cold ); warm ( ). moist ); dry ( ). Grooming: ________; posture: Demeanor/attitude: Breathing mode: High chest shallow ( ); hyperpnea ( ). 307 308 APPENDIX Sighing: frequent ( ); occasional ( ); absent ( ). Occupation: Contact with: dust ( ); fibers (); paints ( ); solvents ( ); sprays ( ); detergents ( ). Other chemicals or airborne particles: Status: Married ( ); single ( ); divorced ( ); other: children: No. Boys ( ); No. Girls ( ). Physician(s) of record: Last medical examination: _________,199__ Diagnos(e)s: 'Ireatmentts): Medication(s): Do you now have, have you ever had, or has any family member related to you by blood (mother, father, sister, brother, familial grandparents or uncles and aunts) had: ( ) High blood pressure () Heart disease APPENDIX 309 ) Low blood pressure ) Angina ) Diabetes (insulin-dependent) ) Anemia ) Diabetes (non-insulin- ) Allergies dependent) ) Dermatitis ) Colitis ) Muscle spasms ) Gastritis ) Tingling in hands and/or feet ) Ulcer ) Fainting (syncope) ) Shortness of breath ) Dizziness (vertigo) ) Asthma ) Stroke ) Emphysema ) Headache ) Hyperventilation ) TMJlbruxism ) Mitral valve prolapse ) Chronic low backache ) Other heart murmur ) EB virus (mononucl.) ) Heart arrhythmia ) PMS ) Chronic vaginal yeast ) Chronic tiredness ) Cystitis ) Menstrual irregul. ) Raynaud's disease ) Tinnitus ) Chronic pain ) Hyperthyroid ) Eating disorder -

Kuban State Medical University" of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation

Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education «Kuban State Medical University" of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation. ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЕ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ БЮДЖЕТНОЕ ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ВЫСШЕГО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ «КУБАНСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ МЕДИЦИНСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ» МИНИСТЕРСТВА ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ (ФГБОУ ВО КубГМУ Минздрава России) Кафедра пропедевтики внутренних болезней Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases BASIC CLINICAL SYNDROMES Guidelines for students of foreign (English) students of the 3rd year of medical university Krasnodar 2020 2 УДК 616-07:616-072 ББК 53.4 Compiled by the staff of the department of propaedeutics of internal diseases Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education «Kuban State Medical University" of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation: assistant, candidate of medical sciences M.I. Bocharnikova; docent, c.m.s. I.V. Kryuchkova; assistent E.A. Kuznetsova; assistent, c.m.s. A.T. Nepso; assistent YU.A. Solodova; assistent D.I. Panchenko; docent, c.m.s. O.A. Shevchenko. Edited by the head of the department of propaedeutics of internal diseases FSBEI HE KubSMU of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation docent A.Yu. Ionov. Guidelines "The main clinical syndromes." - Krasnodar, FSBEI HE KubSMU of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation, 2019. – 120 p. Reviewers: Head of the Department of Faculty Therapy, FSBEI HE KubSMU of the Ministry of Health of Russia Professor L.N. Eliseeva Head of the Department -

EMS Quick Study Guide NOTICE: You DO NOT Have the Right to Reprint Or Resell This Publication

Presents The EMS Quick Study Guide NOTICE: You DO NOT Have the Right to Reprint or Resell this Publication. You Also MAY NOT Give Away, Sell or Share the Content Herein. If you purchased this book/ebook from anywhere other than http://www.ems-safety.com , you have a pirated copy. Please help stop Internet crime by reporting this to: [email protected] © Copyright The EMS Professional ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any informational storage or retrieval system without the expressed written, dated and signed permission from the author. DISCLAIMER AND/OR LEGAL NOTICES: The information presented herein represents the views of the author as of the date of publication. Because of the rate with which conditions change, the author reserves the right to alter and update this information based on the new conditions. The publication is for informational purposes only. While every attempt has been made to verify the information provided in this publication, neither the author nor its affiliates/partners assume any responsibility for errors, inaccuracies or omissions. Any slights of people or organizations are unintentional. If advice concerning medical, legal or related matters is needed, the services of a fully qualified professional should be sought. You should be aware of any laws/practices or local policies which govern emergency care or other pre hospital care practices in your country and state. -

Physical Examination of the Adult Patient with Respiratory Diseases: Inspection and Palpation

Eur Respir J, 1995, 8, 1584–1593 Copyright ERS Journals Ltd 1995 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.95.08091584 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 SERIES 'CHEST PHYSICAL EXAMINATION' Edited by J.C. Yernault Physical examination of the adult patient with respiratory diseases: inspection and palpation B. Maitre, T. Similowski, J-P. Derenne Physical examination of the adult patient with respiratory diseases: inspection and pal- Service de Pneumologie et de Réanimation, pation. B. Maitre, T. Similowski, J-P. Derenne. ©ERS Journals Ltd 1995. Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, ABSTRACT: Inspection of the thorax identifies the breathing position adopted by France. the patient, the shape of the thorax, the dynamics of respiration (breathing pat- tern, symmetry of expansion, mechanics and synchrony of rib cage and abdominal Correspondence: T. Similowski movements). Inspection of the neck adds useful information, particularly with Service de Pneumologie et de Réanimation respect to the dynamics of breathing. Palpation ascertains the signs suggested by Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière inspection with respect to the mechanics of breathing. It also assesses the state of 47-83 Bd de l'Hôpital 75651 Paris Cedex 13 the pleura and pulmonary parenchyma by studying the tactile fremitus. It inte- France grates extrarespiratory signs, such as enlarged lymph nodes or breast abnorma- lities. Extrathoracic respiratory signs should also be systematically looked for, Keywords: Clinical examination including cyanosis, finger deformation, pulsus paradoxus, and pursed lips breath- inspection ing. palpation Interobserver agreement about respiratory signs has repeatedly been studied, and respiratory system generally found to be low, as are clinical-functional correlations. -

Breathing Patterns Breathsounds

By Breathing Patterns BreathSounds Breathing isn’t just a matter of inhaling the good air and exhaling the bad used air. The entire respiratory pattern is important. Rate, depth, timing, and consistency of breaths are all important to the delicate balance of respiration and metabolism. Certain illnesses or injuries can cause changes in the breathing pattern. Changes other than the typical fast or slow breathing that is most common with many conditions. Below are some of the less common breathing patterns that make many healthcare professionals ask themselves… “Hey, what is that pattern anyway?” Breathing Patterns: 1. Cheyne-Stokes respirations a. Definition: This respiratory pattern is characterized by periods of respirations during which the tidal volume starts shallow and gets progressively deeper, and then gets progressively shallower. This shallow-deep-shallow pattern is followed by periods of significant apnea that can last up to 30 seconds or longer, then the cycle starts over. Each cycle can take anywhere between 30 seconds and 2 minutes or longer. b. Causes: This pattern of respiration is often caused by strokes, traumatic brain injuries, brain tumors, carbon monoxide poisoning, and metabolic encephalopathy. This pattern of respiration can be seen in healthy patients experiencing first-time high altitude sickness, and can also be a normal side-effect of morphine administration. 2. Biot’s breathing (aka cluster respiration) a. Definition: A respiratory pattern characterized by periods or “clusters” of rapid respirations of near equal depth or VT followed by regular periods of apnea. b. Causes: Biot’s breathing can be caused by damage to the medulla oblongata by stroke (CVA) or trauma, pressure on the medulla due to uncal or tentorial herniation. -

Glossary of Definitions, Abbreviations, Symbols and Normal Values

Glossary of definitions, abbreviations, symbols and normal values See also index for definitions in the text. a useful measure of aerobic capacity for Values in [square brackets] are from the USA monitoring endurance training, but of (all values are approximate). limited value in severe COPD because peak 2,3-DPG Enzyme in red blood cells, t in exercise levels are often reached below the chronic hypoxaemia, shifting O2 dissociation anaerobic threshold. In normal subjects, curve to right and allowing easier unload anaerobic threshold can be increased by ing of O2 to hypoxic tissues. 25-40%. A Alveolar, e.g. P A02. Angioplasty Invasive but non-surgical dila a Arterial, e.g. Pa02. tation of coronary artery stenosis, using ACBT Active cycle of breathing techniques. catheter via femoral puncture, or laser. ACE inhibiters Angiotensin-converting en- Anoxia Synonymous with hypoxia, although zyme inhibiter drugs, for hypertension, implying a more complete oxygen lack. e.g. captopril, enalapril. AP Anteroposterior. ACPRC Association of Chartered Physio APACHE Acute Physiology And Chronic therapists in Respiratory Care. Health Evaluation (scoring system to meas ADL Activities of daily living. ure severity of illness). Adult respiratory distress syndrome Alterna Apgar score Combined measurement of heart tive name for acute respiratory distress rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex syndrome. irritability and colour (scoring system to Aerosol Suspension of particles in a gas measure birth asphyxiation). stream. Therapeutic aerosols are for Apneustic breathing Prolonged inspiration humidification and drug delivery, other usually due to brain damage. aerosols spread some lung infections and Apnoea Absence of breathing for > 10 allow damage from noxious agents. -

Common Respiratory Issues Near the End of Life

E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium “Respiratory Issues at End-of-Life” Module 3: Jerry Boltz, FNP Nonpain Symptoms at the January 27, 2012 End of Life Part I E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum Common Respiratory Issues Dyspnea: Definition Near the End of Life • Distressing shortness of breath, air • Dyspnea hunger, or difficulty breathing • • Associated with anxiety, depression, Cough and decreased quality of life • Changes in respiratory rate & rhythm • Can be acute or chronic • Increased Respiratory secretions • Sometimes occurs or worsens only with activity E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum Dyspnea: A subjective Feeling • Dyspnea refers to the sensation of difficult or uncomfortable breathing. It is a subjective experience perceived and reported by an affected patient. E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum 1 Dyspnea Dyspnea Major Pulmonary Causes • Major Cardiac causes Tumor Infiltration Pleural Effusion Aspiration COPD – Congestive Heart Failure Pneumonia Bronchospasm – Pulmonary edema Pulmonary Embolism Pulmonary Fibrosis – Superior Vena Cava Syndrome Pulmonary Hypertension Thick Secretions caused by infectious diseases or – Pericardial Effusion dehydration… – Cardiac disease - arrhythmias Thick secretions caused by Us? Later E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum E L N E C Geriatric Curriculum Dyspnea Dyspnea • Cancer Related Causes • Major Neuromuscular Causes – – Metastatic disease from any primary site Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) – – Obstruction -

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY of PULMONARY SYSTEM 2 Test

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF PULMONARY SYSTEM 2 9. Expiratory dyspnea characterizes the followings: Test control 1) broncho-obstructive syndrome 1. The external respiratory failure is the most likely characterized by: 2) stenosis of trachea 4) attack of bronchial asthma 1) dyspnea 5) hypercapnia 3) the second stage of asphyxia 5) edema of larynx 2) cyanosis 6) hypocapnia 6) chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases 3) hypoxia 7) acidosis 10. Point out the possible consequences of early expiratory closure of 4) hypoxemia 8) alkalosis conducting airways: 2. The acute respiratory failure in compensatory stage is characterized by: 1) increased maximal alveolar ventilation per minute 1) PaO2 lower than 60 mm Hg 3) PaO2 higher than 60 mmHg 2) decreased maximal alveolar ventilation per minute 2) PaCO2 lower than 35 mm Hg 4) PaCo2 higher than 45 mmHg 3) decreased residual volume 4) increased residual volume 3. The acute respiratory failure in decompensatory stage is characterized by: 5) lymphostasis 6) hypoxemia 1) PaO2 lower than 60 mmHg 3) PaO2 higher than 60 mmHg 11. What are the causes for early expiratory closure of conducting airways 2) PaCO2 lower than 35 mm Hg 4) PaCO2 higher than 45 mmHg during expiration? 4. Which of the indexes of flow-volume test the most likely show the 1) decreased resistance to airflow obstruction of upper conductive airways? 2) increased resistance to airflow 1) reduction of flow volume –velocity at the level 75% VC 3) increased laminar axis pressure of airflow in bronchiole 2) reduction of flow volume-velocity at the level 50% VC 4) increased radial pressure of airflow in bronchiole 3) reduction of flow volume –velocity at the level 25% VC 5) decreased radial pressure of airflow in bronchiole 4) decreased top of flow-volume curve 6) increased transpulmonary pressure 5. -

Special Pathophysiology Respiratory System

SPECIAL PATHOPHYSIOLOGY RESPIRATORY SYSTEM 1. The hypoxic-hyperoxic lesion of alveolocytes type II leads to: 1. Mucus hypersecretion. 2. Disturbed synthesis of antiprotease inhibitor. 3. Ig A hyposecretion. 4. Secretion of specific enzymes. 5. Insufficient surfactant production. 2. Surfactant deficiency in the alveoles leads to: 1. Lyophilization of the alveolar membrane. 2. Expiratory collapse of the alveoles. 3. Substrate deficit in the alveoles. 4. Sudden stop of breathing. 5. Abrupt decrease of alveolar pressure. 3. Which respiratory stimulator best reflects the level of damage to the respiratory center? 1. Decreased рО2. 2. Increased рСО2. 3. Decreased рН. 4. Apomorphine. 5. Hyperprogesteronemia. 4. When the pleural cavity is filled with fluid this leads to: 1. Lung collapse and atelectasis. 2. Inhibited stimulation of the respiratory center. 3. Lung immune deficiency. 4. Increased proliferation of alveolar macrophages. 5. Increased lung compliance. 5. Which defense mechanism of the respiratory system has a reflex character? 1. Cough. 2. Alveolar macrophage system. 3. Mucocilliary escalator. 4. Antioxidant systems. 5. Nasopharyngeal filter. 6. Which of the following should be decreased for the patient to have oligopnea? 1. Dead space. 2. Tidal volume. 3. Respiratory rate. 4. Ventilation. 5. Diffusion. 7. Hyperpnea is breathing with: 1. Increased respiratory rate. 2. Increased tidal volume. 3. Increased ventilation. 4. Inadequately high effort. 5. Periodical apneic pauses. 8. The most important outcome of alveolar hypoventilation is: 1. Cyanosis. 2. Increased airway resistance. 3. Dyspnea. 4. Orthopnea. 5. Respiratory acidosis. 9. Which pathologic type of breathing represents with lung hyperventilation and alveolar hypoventilation at the same time? 1. Bradypnea with hyperpnea. -

Oxygenation Adventitious Breath Sounds Abnormal Breath Sounds

Oxygenation Adventitious breath sounds Abnormal breath sounds Apnea Cessation of respirations Atelectasis Collapse of a portion of the lung; specifically alveolar collapse Biot's (cluster) respirations Shallow breaths interrupted by apnea; may be seen in clients with central nervous system disorders Bradypnea Low respiration rate (<12 breaths per minute) Cheyne-Stokes respirations Marked rhythmic waxing and waning of respiration from very deep to very shallow breathing and temporary apnea; common causes include congestive heart failure, increased intracranial pressure, and overdose of certain drugs Cyanosis A bluish discoloration of the skin, nail beds and mucous membranes due to reduced hemoglobin-oxygen saturation Diffusion Movement of gases or other particles from an area of greater pressure of concentration to an area of lower pressure or concentration Dyspnea Difficult or uncomfortable breathing Emphysema A form of COPD; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; a chronic lung ailment that makes ventilation difficult Erythrocytes Red blood cells; men average 5 million erythrocytes per cubic milliliter of blood; women average 4.5 million erythrocytes per cubic milliliter of blood; Eupnea Normal respiration Expectorate “Spit out” Hematocrit The percentage of the blood that is erythrocytes; average hematocrit is 40%-54% in men, and 37%-50% in women Hemoglobin Oxygen-carrying red pigment in red blood cells Humidifiers A device that adds water vapor to inspired air Hypercapnia / Hypercarbia Accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood Hypoxemia A condition of insufficient oxygen in the blood; characterized by a low partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood or low hemoglobin saturation Hypoxia A condition of insufficient oxygen anywhere in the body Hypoxemic hypoxia Hypoxia as a result of decreased O2 levels of the blood. -

Renal & Electrolyte Disturbances

Renal & Electrolyte Disturbances 20% 6% 80% 186 RENAL I. INTRODUCTION AACN-CCRN/CCRN-E 6% Chronic Renal Failure Acute Renal Failure Life Threatening Electrolyte Disturbances II. RENAL PHYSIOLOGY Major Functions of the Kidney 1. Excretion of Metabolic Wastes 2. Urine Formation 3. Acid-Base Balance Regulation 4. Electrolyte Regulation 5. Fluid Regulation 6. Blood Pressure Regulation 7. Erythropoietin Secretion/Anemia Regulation Renal Assessment 1. Blood Work Blood Urea Nitrogen Creatinine Serum Electrolytes Hgb & Hct Serum Albumin Serum Osmolality Blood Urea Nitrogen: BUN: 5.0 – 25 mg/dL Urea is formed in the liver along with C02 as a waste by product of protein metabolism. It is carried by the blood and excreted by the renal system. Elevated BUN levels are significant for either increased protein catabolism or decreased renal excretion of urea. Situations, which would increase protein catabolism, include high protein diets, GI bleeding (protein from blood is broken down), DKA, burns and cancer. Any pre-renal (shock state, poor renal perfusion) or intra-renal failure (nephrotoxic medications or kidney diseases) will decrease the GFR and therefore urea excretion. The elevation of the metabolic waste products can cause fatigue, muscle weakness, and seizures. Volume status of the patient can also affect the BUN. Treatment is related to the cause of the elevation, which would include hydration, stopping protein catabolism, and/or dialysis. 187 Creatinine: 0.6 – 1.5 mg/dL slightly lower in females, children and elderly Creatinine is a waste product of creatinine phosphate breakdown. Creatinine phosphate is a high-energy compound found in skeletal muscle tissue and is released during muscle breakdown. -

Congestive Heart Failure

CRITICAL CARE NURSING CARE PLANS Sheree Corner Contributor: Barbara Sage1 R.N., M.s., C.C.R.N. -- -- DELMAR THOMSON LEARNING Africa Australia Canada Denmark Japan Mexico New Zealand Philippines Puerto Rico Singapore Spain United Kingdom United States NOTICE TO THE READER Publisher does not warrant or guarantee any of the products described herein or perform any independent analysis in connection with any of the product information contained herein. Publisher does not assume, and expressly disclaims, any obligation to obtain and include information other than that provided to it by the manufacturer. The reader is expressly warned to consider and adopt all safety precautions that might be indicated by the activities herein and to avoid all potential hazards. By following the instructions contained herein, the reader willingly assumes all risks in connection with such instructions. The Publisher makes no representation or warranties of any kind, including but not limited to, the warranties of fitness for particular purpose or merchantability, nor are any such representations implied with respect to the material set forth herein, and the publisher takes no responsibility with respect to such material. The publisher shall not be liable for any special, consequential, or exemplary damages resulting, in whole or part, from the readers' use of, or reliance upon, this material. COPYRIGHT 0 1998 Delmar, a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. The Thomson Learningm is a trademark used herein under license. Printed in the United States of America 2345678910XXX050403020100 For more information, contact Delmar, 3 Columbia Circle, PO Box 15015, Albany, NY 12212-0515; or find us on the World Wide Web at http://www.delmar.com International Division List Asia AustraliaINew Zealand: Latin America: Thomson Learning NelsonfI'homson Learning Thomson Learning 60 Albert Street, #15-01 102 Dodds Street Seneca, 53 Albert Complex South Melbourne, Victoria 3205 Colonia Polanco Singapore 189969 Australia 11560 Mexico D.F.