Global Research Network Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMMITTEE on the PEACEFUL USES of OUTER SPACE Chaired by Alan Lai

COMMITTEE ON THE PEACEFUL USES OF OUTER SPACE Chaired by Alan Lai Session XXII Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Topic A: Regulating the Militarization of Outer Space Topic B: R egulating Commercial Activity in Outer Space Committee Overview ad hoc committee, with 18 inaugural members, including the two major parties The United Nations Committee on involved in the space race: the United States the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space of America and the Soviet Union. In 1959, (COPUOS) was set up by the United the U.N. General Assembly officially Nations General Assembly in 1959. established COPUOS as a permanent body, Founded because of the implications that which had 24 members at that time.1 the successful launch of Sputnik had for the COPUOS now has 87 members, and world, COPUOS’s mission is to review maintains its goal as “a focal point for international cooperation in peaceful uses international cooperation in the peaceful of outer space, to study spacerelated exploration and use of outer space, activities that could be undertaken by the maintaining close contacts with United Nations, to encourage space governmental and nongovernmental research programmes, and to study legal organizations concerned with outer space problems arising from the exploration of activities, providing for exchange of 1 outer space. information relating to outer space The United Nations realized early on activities and assisting in the study of that space would be the next frontier for measures for the promotion of international exploration, and so it has been involved in cooperation in those activities.”2 In addition space activities since the beginning of the to being one of the largest committees in space age. -

WIC Template

1 Talking Point 6 Week in 60 Seconds 7 Economy Week in China 8 Cross Straits 9 Internet and Tech 10 China and the World 11 Banking and Finance 13 Chinese Consumer 14 Energy and Resources 26 April 2013 15 Society and Culture Issue 190 18 And Finally www.weekinchina.com 19 The Back Page Not without conditions m o c . n i e t s p e a t i n e b . w w w Calling a halt: why China’s antitrust bosses are flexing their muscles in international M&A Brought to you by Week in China Talking Point 26 April 2013 Strings will be attached International M&A deals now face a formidable hurdle: China ong stretches of China’s com - What’s the background to the Lmercial history have been about latest antitrust cases? defending domestic monopo - Beijing has granted approvals lies rather than worrying for two high-profile deals this about anti-competitive be - month. First to get the green haviour. The manufacture of light was Glencore’s $30 billion silk was protected on pain of takeover of Xstrata. The deal death, for instance, with the had proved challenging from threat of a grisly end for any - the start, living up to its Everest one caught smuggling silk - codename (John Bond, depart - worms out of the country. ing chairman of Xstrata, and Si - That stopped the trade from mon Murray, who chairs Glen - arriving on the fringes of Eu - core, are both said to be rope until the middle of the mountaineering enthusiasts). sixth century, when two There was even last-minute Nestorian monks brought silk - drama, when former British worm eggs to the court of the leader Tony Blair was called Emperor Justinian in Byzan - in to bridge differences be - tium. -

Exoplanet Exploration Collaboration Initiative TP Exoplanets Final Report

EXO Exoplanet Exploration Collaboration Initiative TP Exoplanets Final Report Ca Ca Ca H Ca Fe Fe Fe H Fe Mg Fe Na O2 H O2 The cover shows the transit of an Earth like planet passing in front of a Sun like star. When a planet transits its star in this way, it is possible to see through its thin layer of atmosphere and measure its spectrum. The lines at the bottom of the page show the absorption spectrum of the Earth in front of the Sun, the signature of life as we know it. Seeing our Earth as just one possibly habitable planet among many billions fundamentally changes the perception of our place among the stars. "The 2014 Space Studies Program of the International Space University was hosted by the École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) and the École des Hautes études commerciales (HEC), Montréal, Québec, Canada." While all care has been taken in the preparation of this report, ISU does not take any responsibility for the accuracy of its content. Electronic copies of the Final Report and the Executive Summary can be downloaded from the ISU Library website at http://isulibrary.isunet.edu/ International Space University Strasbourg Central Campus Parc d’Innovation 1 rue Jean-Dominique Cassini 67400 Illkirch-Graffenstaden Tel +33 (0)3 88 65 54 30 Fax +33 (0)3 88 65 54 47 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.isunet.edu France Unless otherwise credited, figures and images were created by TP Exoplanets. Exoplanets Final Report Page i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The International Space University Summer Session Program 2014 and the work on the -

Edristi-Navatra-July-2021.Pdf

Preface Dear readers, we have started edristi English edition as well since August, 2015. We are hopeful that it will help us to connect to the broader audience and amplify our personal bonding with each other. While presenting Day-to-day current affairs, we are very cautious on choosing the right topics to make sure only those get the place which are useful for competitive exams perspective, not to increase unnecessary burden on the readers by putting useless materials. Secondly, we have also provided the reference links to ensure its credibility which is our foremost priority. You can always refer the links to validate its authenticity. We will try to present the current affairs topics as quickly as possible but its authenticity is given higher priority over its turnaround time. Therefore it could happen that we publish the incident one or two days later in the website. Our plan will be to publish our monthly PDF on very first day of every month with making appropriate modifications of day-to-day events. In general, the events happened till 30th day will be given place in the PDFs. The necessity of this is to ensure the contents factual authenticity. Reader’s satisfaction is our utmost priority so requesting you to provide your valuable feedback to us. We will warmly welcome your appreciation/criticism given to us. It will surely show us the right direction to improve the content quality. Hopefully the current affairs PDF (from 1st July to 31st July) will benefit our beloved readers. Current affairs data will be useless if it couldn’t originate any competitive exam questions. -

July-28-2021

INS IDE... WEDNESDAY, JULy 28, 2021 KELLY CRANE RECOGNIZED AS IRON IRON COUNTY WATER STEWARD COUNTY VOL. 13 NO. 35 IRONCOUNTYTODAY.COM WEDNESDAY, JULy 28, 2021 life 4 Opinion Meeting the 7 Showcase Sorrowing 8 Life Harrison IRON 16 Sports Family 18 Classifieds COUNTY 21 Comics/Puzzles Rain Reigns As returning rain reigns in Southern Utah so does the gratitude from the ground and all things that grow and live upon it. CONNIE BARLOW, BERYL, UT Sons of the Utah Pioneers turning hearts of children to their grandfathers from Don Anderson winners have had very special When Kathryn (who is a sister to Kaleb Lopez, who was the first- FOR IRON COUNTY TODAY experiences during the writing of Kyle’s grandmother Irene Tebbs) place winner for East Elementary, also their essays. heard about Kyle winning the contest, had a meaningful experience with Fourth graders study Utah Kyle Tebbs won the prestigious she asked him to come visit and read his essay. Kaleb and his family are in history in school and this year 352 of First Place award for the school his essay to her. When he did, she Hawaii at the funeral of the grand- them wrote an essay about a family district for his essay on his late was so impressed she asked what his father he wrote about in his essay. member or a person in Utah history, grandfather Richard Tebbs. When award had been. When Kyle reported He was not back in time to attend and they were all excellent. They Howard called to remind Kyle about he had received $75 and was the our Town Meeting, but Kaleb shared were also given about $700 in cash the SUP Town Meeting on July 24, his overall winner in the school district, his essay as part of his grandfather’s and prizes. -

AEROPAC Spring 2016 Newsletter

Association of Experimental Rocketry of the Pacific Volume 22 Issue 1 TRIPOLI Rocketry Association, Inc. Prefecture No. 23 May 2016 AEROPAC Spring 2016 Newsletter Photo by Phoenix 4, courtesy of Curt Von Delius President’s Pad Jim Green What’s Inside Greetings, fellow AEROPAC mem- Page 4 - Recognition, Awards for Dr. Lynn Cominsky bers! Page 7 - Project ARQUE We will be starting this year’s Page 12 - AEROPAC’s New Wireless Launch System launches with a shiny new wireless Page 16 - ARLISS Date Logger Project—Part 2 launch system. Thanks to Gene Page 24 - AEROPAC 2016 Equipment Cleaning Party Engelgau for researching, purchas- ing, and testing this new system. Page 26 - TRA’s > 50k’ Black Rock Flight Process Page 40 - ARLISS Flyers Support Magnitude.io Stem The equipment cleaning party Education Program / Chat with Magnitude.io went well thanks to the crew of volunteers who cleaned last year’s crud off our rails, rods and other equipment. Thanks also to Lynn after all. Cominsky for letting us use her The FAA has re-evaluated the hazards around our launch area and is property for the job. reducing our daily waiver altitude. High flights will have to be done There are reports of dry playa so during the Saturday morning window. I’ll send out more information MUDROCK might not be so muddy when the waiver has been processed. © AERO‐PAC Inc. 2016 Association of Experimental Rocketry of the Pacific Volume 22 Issue 1 TRIPOLI Rocketry Association, Inc. Prefecture No. 23 May 2016 2© AERO‐PAC Inc. 2016 Association of Experimental Rocketry of the Pacific Volume 22 Issue 1 TRIPOLI Rocketry Association, Inc. -

The Economic Battle for Space, What China Understands That We Don’T

Lt. General Steven Kwast - Space war EP82 CLEARED FOR RELEASE 04/09/2020 [Economic Battle PlanTM points: 97) The Economic Battle for Space, What China Understands That We Don’t Lt. General Steven Kwast joins the Economic War Room for your briefing this week. We have seen the economic impact of the Chinese coronavirus, but sadly that is minimal compared to the economic threat we face if we lose the Space Race. The country that controls the electromagnetic spectrum can paralyze economies and block information. It’s all about quantum energy, artificial intelligence, and the design of data. The space economy can be built for the good of all mankind, but right now Chinese Communist Party is focused on controlling it for their purposes. In space, it is critical America owns the gateways, so we can provide information to all Americans or anybody who believes in our values. The key is that we maintain the values of trust, liberty, privacy and independence that we expect as individuals. As Americans, we need to continue to look forward and not backward. We need to be prepared for the unexpected and recognize it is not time to operate in a “business as usual” format. Too often militaries, civilizations and organizations get comfortable doing things the way they have always done them. They assume they are too big to fail. Yet, throughout history we have seen civilizations and big corporations fall that looked unbeatable. They ultimately fail because some other challenger or adversary shifts the paradigm and attacks in another way. “The civilization that has a more powerful economy will always be able to defend its freedom to act and to do things they want to do.” –Lt. -

SPACE RACE: Commercialising the Path

SPACE RACE: Commercialising the Path Point-of-View July 2021 Contents From race of superpowers Roads to success to race of billionaires in exploring space What is shaping the space Who are in the space exploration industry of today? race of today? Future of in-space economy Introduction to What benefits will a space journey space exploration bring Executive summary for the economy? 2 Introduction to a space journey Journey into space started 50 years ago with nations’ race making first steps using moderate technology at hand… Key elements of space journey 50 years ago Nations’ Space race Single use rockets & costly shuttles First milestones achieved: 1st man in space Industry drivers: 1st step on the Moon ideology & national pride 1st space station 3 Source: BDO Centers analysis Introduction to a space journey …and continues with visionary leaders driving space into the era of affordable travel and game-changing projects Key elements of space journey now Billionaires’ Space race Ambitious projects Reusable, cheap, are about to come true: and big rockets moon base, people on Mars & beyond, space tourism Industry drivers: commercialisation & business leaders’ aspiration 4 Source: BDO Centers analysis Introduction to a space journey Active exploration and rapid growth of the global space industry enable multilateral perspectives in the future Key space players Prospective in-space industries Elon Musk Jeff Bezos Enable the Build the low-cost road to colonisation of Mars space to enable near-Earth Space Space logistics Space hospitality Space -

Aviation Week & Space Technology

STARTS AFTER PAGE 34 MRO’s Bumpy Path Rolls Speeds Back to Recovery to Supersonics ™ $14.95 AUGUST 17-30, 2020 ADVANCING AIR MOBILITY Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

Supreme Leadership"

Praise for "Supreme Leadership" Supreme read! You may not recognize these CEOs’ names, but the lessons they share resonate loud and deep. – Ludovic Beaufils | Vice President Product Marketing, Whirlpool I have always believed it is always about people. This book tells you how and why. – Neville Isdell | ex-Chairman & CEO, the Coca-Cola Company and ex-board member, General Motors A great book to teach you, or remind you, of some of the most important ideas that form the foundation of business and life success. – John Spence | one of the Top 100 business thought leaders in America This book is a must read for anyone who is or wants to be a true leader. It’s new, fresh and the stories are supreme. Supreme Leadership will change you and the people you surround yourself with if you read it and use the very practical examples. This book will show you how to go from great to supreme. – Robert Shemin | New York Times bestselling author * * * This is the definitive leadership playbook. Follow the advice inside here and you'll learn what it takes be a leader worth following. – Paul Sohn | bestselling author of Quarter-Life Calling, leadership coach and speaker A powerful, practical guide that shows you how to make it to your company’s 25th anniversary… from people who’ve done that and more. – David Burkus | associate professor of leadership and innovation, Oral Roberts University; author of Under New Management Nothing beats experience, especially in leadership. If you want direct knowledge from leaders who have faced what you will, Alinka Rutkowska brings you unfiltered, honest accounts directly from leaders who have been there. -

English and Tamil Medium Syllabus for Students of Classes I to XII

CONTENTS TNPSC BITS ........................................................................................................................................... 15 TAMIL NADU .......................................................................................................................................... 23 New and 30th Director General of Police - Tamil Nadu ..................................... 23 S.Peter Alphonse ............................................................................................ 24 Kudankulam - 5th power unit .......................................................................... 24 Mariyappan Thangavelu - flag bearer .............................................................. 25 DGP Selection Process (Tamilnadu) ................................................................ 25 TNAU identifies grasses & trees to improve Elephant Habitats ....................... 26 Tamil Nadu Athletes to Tokyo Olympics ......................................................... 26 Head of Tamil Nadu Textbook and Educational Services Corporation ............. 26 Bionychiurus tamilensis ................................................................................. 27 New members to TNPSC ................................................................................. 27 Terracotta container - Keezhadi ..................................................................... 27 Doorstep care to cut deaths due to diabetes & BP – TN ................................... 28 AK Rajan committee report ........................................................................... -

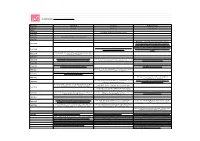

Billionaire Space Race DATA

RS Components: https://uk.rs-online.com/web/ Billionaire: Elon Musk Jeff Bezos Richard Branson Company: SpaceX Blue Origin Virgin Galactic YEARS Year 2000 Sept 2000: Jeff Bezos founds Blue Origin Year 2001 Year 2002 May 2002: Elon Musk founds SpaceX Year 2003 Early 2004: Richard Branson founds Virgin Galactic. Year 2004 October 2004: SpaceShipOne takes three people to space over two weeks, winning a $10m Ansari X Prize August 2005: Virgin Galactic starts accepting refundable March 2005: Blue Origin's first flight test vehicle, Charon, Year 2005 deposits from customers, raising $10m in a matter of makes its first and only test flight weeks March 2006: The first Falcon 1 launch fails a minute into Year 2006 ascent due to a fuel leak Year 2007 Sept 2008: The Falcon 1 becomes the first privately 2008: Blue Origin reveal plans for the 'New Shepard', stating December 2008: Launch vehicle VMS (Virgin Mother Ship) Year 2008 developed liquid-fuel rocket to enter Earth's orbit it will fly unmanned in 2011, and manned in 2012 Eve, has a successful test flight Year 2009 December 2010: SpaceX becomes the first private company March 2010: VSS (Virgin Space Ship) Enterprise, makes its Year 2010 to launch, orbit and recover a spacecraft first free flight, lasting 6 hours April 2011, Blue Origin receive a commitment from NASA for Year 2011 $22m under the CCDev phase 2 programme 25/05/2012: SpaceX is the first private company to send and Year 2012 dock a spacecraft at the I.S.S April 2013: The first rocket-powered test flight of Year 2013 SpaceShipTwo