Midwest Institute of Health V Whitmer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deborah L. Rhode* This Article Explores the Leadership Challenges That Arose in the Wake of the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic and the W

9 RHODE (DO NOT DELETE) 5/26/2021 9:12 AM LEADERSHIP IN TIMES OF SOCIAL UPHEAVAL: LESSONS FOR LAWYERS Deborah L. Rhode* This article explores the leadership challenges that arose in the wake of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread protests following the killing of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd. Lawyers have been key players in both crises, as politicians, general counsel, and leaders of protest movements, law firms, bar associations, and law enforcement agencies. Their successes and failures hold broader lessons for the profession generally. Even before the tumultuous spring of 2020, two-thirds of the public thought that the nation had a leadership crisis. The performance of leaders in the pandemic and the unrest following Floyd’s death suggests why. The article proceeds in three parts. Part I explores leadership challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and the missteps that put millions of lives and livelihoods as risk. It begins by noting the increasing frequency and intensity of disasters, and the way that leadership failures in one arena—health, environmental, political, or socioeconomic—can have cascading effects in others. Discussion then summarizes key leadership attributes in preventing, addressing, and drawing policy lessons from major crises. Particular attention centers on the changes in legal workplaces that the lockdown spurred, and which ones should be retained going forward. Analysis also centers on gendered differences in the way that leaders addressed the pandemic and what those differences suggest about effective leadership generally. Part II examines leadership challenges in the wake of Floyd’s death for lawyers in social movements, political positions, private organizations, and bar associations. -

FROH: Press Office of Senator John F. Kennedy 505 Esso Building 261 Constitution Avenue , - \Jashington, D.C

FROH: Press Office of Senator John F. Kennedy 505 Esso Building 261 Constitution Avenue , - \Jashington, D.C. ~ December 1, 1960 BACKGROIDID II.JFORHATION OIJ GOVERNOR G. MENilEN HILLIAMS rm'.o.t-' Gerhard Mennen Hilliams, born Detroit 1 Michigan> February 23, 1911 Education: Liggett School Detroit University School Salisbury School (1929) Princeton University - AB, Phi Beta Kappa 1933 University of l'Iichigan School of Lav1 - JD 1936 Married nancy ~uirl~ > June 26, 1937. Three children, Gery, nancy and Hendy Honorary Degrees: \Jilberforce University - 1951 - Doctor of Laws Lawrence Institute of Technology - 1952 - Doctor of Humanities Ivlichigan State University - 1955 - Doctor of Laws University of Liberia - 1953 - Doctor of Laws University of Michigan - 1959 - Doctor of Laws A~uinas Colle~e - 1959 - Doctor of Laws Government Service: Attorney> Social Security Board - 1936 Assistant Attorney General, State of Hichigan - 19J3 Executive Assistant U.S. Attorney General - 1939 Special Assistant u.s. Attorney General - 1940 Deputy Director OPA, Michigan 1947 Elected Governor of Michigan 194~ ;· inaugurated Governor January 1, 1949 and has served continuously six terms since. Armed Forces: Entered U.s. Navy 191.~2, served as intelligence officer on aircraft carrier in Pacific earning 10 uattle stars. Disc~1arged February 1946 with ranl~ of Lt. Commander. Political Activity: Credited ·Hith providing spark which revitalized Democratic Party in Michigan and turned state from Republican to Democratic. Vice Chairman of Democratic national Committee and Chairman of its nationalities Division. :tvlember of Advisory Council, Democratic National Committee Since 1960 national convention and Hichigan primaries he has campaigned actively throughout f4ichigan and the United States in behalf of state and national ticket. -

Chapter VI, Executive Department

A Comparative Analysis of the Michigan Constitution Volume I Article VI Citizens Research Council of Michigan 1526 David Stott Building 204 Bauch Building Detroit, 26, Michigan Lansing 23, Michigan Report Number 208 October 1961 Citizens Research Council of Michigan TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER VI EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT Page A. State Officers - Election and Term 1 B. General Powers of the Governor - Executive Organization 9 C. The Governor’s Power of Appointment and Removal 22 1. Power of Appointment 22 2. Power of Removal 27 D. Civil Service Commission 32 E. The Governor’s Relations with the Legislature 41 1. Messages to the Legislature 41 2. Writs of Election for Legislative Vacancies 42 3. Convening Special Legislative Session 43 4. Convening Legislature Elsewhere Than at State Capital 45 5. Gubernatorial Veto 46 6. Item Veto 53 F. Other Powers of the Governor 56 1. Military Powers 56 2. Reprieves, Commutations and Pardons 58 3. Use of the Great Seal 62 VI Executive Department 4. Issuance of Commissions 63 G. Eligibility, Lieutenant Governor, Succession and Other Provisions 65 1. Eligibility to Office of Governor 65 2. Prohibition of Dual Office Holding and Legislative Appointment 66 3. Lieutenant Governor 68 4. Devolution of the Governor’s Powers upon Lieutenant Governor 72 5. Succession Beyond Lieutenant Governor 76 6. Compensation of State Officers 78 7. Boards of State Auditors, Escheats and Fund Commission 80 (See over for Section detail) Page Article VI, Section 1 ...................................................................... -

Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the Western District of Michigan

Case 1:20-mj-00416-SJB ECF No. 1 filed 10/06/20 PageID.1 Page 1 of 1 AO 91 (Rev. 11/11) Criminal Complaint UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the Western District of Michigan United States of America ) v. ) Adam Fox, Barry Croft, Ty Garbin, Kaleb Franks, ) Case No. Daniel Harris and Brandon Caserta ) 1 :20-mj-416 ) ) ) Defendant(s) CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, the complainant in this case, state that the following is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. On or about the date(s) of June 2020 to the present in the county of Kent and elsewhere in the Western District of Michigan , the defendant(s) violated: Code Section Offense Description 18 U.S.C. § 1201(c) Conspiracy to commit kidnapping This criminal complaint is based on these facts: ,/ Continued on the attached sheet. 4-;:If} aznant ..s signature RICHARD TRASK, Special Agent Printed name and title Sworn to before me and signed in my presence. October 6, 2020 Date: -----~ --- City and state: Grand Rapids, Michigan Sally J. Berens, U.S. Magistrate Judge Printed name and title Case 1:20-mj-00416-SJB ECF No. 1-1 filed 10/06/20 PageID.2 Page 1 of 15 CONTINUATION OF A CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, Richard J. Trask II, being first duly sworn, hereby depose and state as follows: 1. I am a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and have been since April 2011. As a Special Agent with the FBI, I have participated in, and conducted numerous investigations under the Domestic Terrorism, Counterterrorism, and Counterintelligence programs, to include espionage, terrorism, and domestic extremism investigations. -

National Governors' Association Annual Meeting 1977

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING 1977 SIXTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING Detroit. Michigan September 7-9, 1977 National Governors' Association Hall of the States 444 North Capitol Street Washington. D.C. 20001 Price: $10.00 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 12-29056 ©1978 by the National Governors' Association, Washington, D.C. Permission to quote from or to reproduce materials in this publication is granted when due acknowledgment is made. Printed in the United Stales of America CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Standing Committee Rosters vii Attendance ' ix Guest Speakers x Program xi OPENING PLENARY SESSION Welcoming Remarks, Governor William G. Milliken and Mayor Coleman Young ' I National Welfare Reform: President Carter's Proposals 5 The State Role in Economic Growth and Development 18 The Report of the Committee on New Directions 35 SECOND PLENARY SESSION Greetings, Dr. Bernhard Vogel 41 Remarks, Ambassador to Mexico Patrick J. Lucey 44 Potential Fuel Shortages in the Coming Winter: Proposals for Action 45 State and Federal Disaster Assistance: Proposals for an Improved System 52 State-Federal Initiatives for Community Revitalization 55 CLOSING PLENARY SESSION Overcoming Roadblocks to Federal Aid Administration: President Carter's Proposals 63 Reports of the Standing Committees and Voting on Proposed Policy Positions 69 Criminal Justice and Public Protection 69 Transportation, Commerce, and Technology 71 Natural Resources and Environmental Management 82 Human Resources 84 Executive Management and Fiscal Affairs 92 Community and Economic Development 98 Salute to Governors Leaving Office 99 Report of the Nominating Committee 100 Election of the New Chairman and Executive Committee 100 Remarks by the New Chairman 100 Adjournment 100 iii APPENDIXES I Roster of Governors 102 II. -

Chronology of Michigan History 1618-1701

CHRONOLOGY OF MICHIGAN HISTORY 1618-1701 1618 Etienne Brulé passes through North Channel at the neck of Lake Huron; that same year (or during two following years) he lands at Sault Ste. Marie, probably the first European to look upon the Sault. The Michigan Native American population is approximately 15,000. 1621 Brulé returns, explores the Lake Superior coast, and notes copper deposits. 1634 Jean Nicolet passes through the Straits of Mackinac and travels along Lake Michigan’s northern shore, seeking a route to the Orient. 1641 Fathers Isaac Jogues and Charles Raymbault conduct religious services at the Sault. 1660 Father René Mesnard establishes the first regular mission, held throughout winter at Keweenaw Bay. 1668 Father Jacques Marquette takes over the Sault mission and founds the first permanent settlement on Michigan soil at Sault Ste. Marie. 1669 Louis Jolliet is guided east by way of the Detroit River, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario. 1671 Simon François, Sieur de St. Lusson, lands at the Sault, claims vast Great Lakes region, comprising most of western America, for Louis XIV. St. Ignace is founded when Father Marquette builds a mission chapel. First of the military outposts, Fort de Buade (later known as Fort Michilimackinac), is established at St. Ignace. 1673 Jolliet and Marquette travel down the Mississippi River. 1675 Father Marquette dies at Ludington. 1679 The Griffon, the first sailing vessel on the Great Lakes, is built by René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and lost in a storm on Lake Michigan. ➤ La Salle erects Fort Miami at the mouth of the St. -

1981 NGA Annual Meeting

PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING 1981 SEVENTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING Atlantic City, New Jersey August 9-11, 1981 National Governors' Association Hall of the States 444 North Capitol Street Washington, D.C. 20001 These proceedings were recorded by Mastroianni and Formaroli, Inc. Price: $8.50 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 12-29056 © 1982 by the National Governors' Association, Washington, D.C. Permission to quote from or reproduce materials in this publication is granted when due acknowledgment is made. Printed in the United States of America ii CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Standing Committee Rosters vi Attendance x Guest Speaker xi Program xii PLENARY SESSION Welcoming Remarks Presentation of NGA Awards for Distinguished Service to State Government 1 Reports of the Standing Committees and Voting on Proposed Policy 5 Positions Criminal Justice and Public Protection 5 Human Resources 6 Energy and Environment 15 Community and Economic Development 17 Restoring Balance to the Federal System: Next Stepon the Governors' Agenda 19 Remarks of Vice President George Bush 24 Report of the Executive Committee and Voting on Proposed Policy Position 30 Salute to Governors Completing Their Terms of Office 34 Report of the Nominating Committee 36 Remarks of the New Chairman 36 Adjournment 39 iii APPENDIXES I. Roster of Governors 42 II. Articles of Organization 44 ill. Rules of Procedure 51 IV. Financial Report 55 V. Annual Meetings of the National Governors' Association 58 VI. Chairmen of the National Governors' Association, 1908-1980 60 iv EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE, 1981* George Busbee, Governor of Georgia, Chairman Richard D. Lamm, Governor of Colorado John V. -

Chronology of Michigan History 1618-1701

CHRONOLOGY OF MICHIGAN HISTORY 1618-1701 1618 Etienne Brulé passes through North Channel at the neck of Lake Huron; that same year (or during two following years) he lands at Sault Ste. Marie, probably the first European to look upon the Sault. The Michigan Native American population is approximately 15,000. 1621 Brulé returns, explores the Lake Superior coast, and notes copper deposits. 1634 Jean Nicolet passes through the Straits of Mackinac and travels along Lake Michigan’s northern shore, seeking a route to the Orient. 1641 Fathers Isaac Jogues and Charles Raymbault conduct religious services at the Sault. 1660 Father René Mesnard establishes the first regular mission, held throughout winter at Keweenaw Bay. 1668 Father Jacques Marquette takes over the Sault mission and founds the first permanent settlement on Michigan soil at Sault Ste. Marie. 1669 Louis Jolliet is guided east by way of the Detroit River, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario. 1671 Simon François, Sieur de St. Lusson, lands at the Sault, claims vast Great Lakes region, comprising most of western America, for Louis XIV. St. Ignace is founded when Father Marquette builds a mission chapel. First of the military outposts, Fort de Buade (later known as Fort Michilimackinac), is established at St. Ignace. 1675 Father Marquette dies at Ludington. 1679 The Griffon, the first sailing vessel on the Great Lakes, is built by René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, and lost in a storm on Lake Michigan. ➤ La Salle erects Fort Miami at the mouth of the St. Joseph River. 1680 La Salle, with a small group, marches across the Lower Peninsula, reaching the Detroit River in ten days, the first Europeans to penetrate this territory. -

Asthana PJM Letter

1 Montana January 8, 2020 Gov. Steve Bullock Chair Delaware Manu Asthana, President and Chief Gov. John Carney Executive Officer Vice Chair PJM Interconnection Executive Director 2750 Monroe Boulevard Larry Pearce Audubon, PA 19403 Dear President Asthana: Please accept our congratulations on your appointment as the president and chief executive officer of PJM Interconnection. Many of the nation’s governors have worked with PJM on a range of issues over the years, and we look forward to continuing that relationship with you and your PJM colleagues. We are entering a new era in which governors and state legislators are increasingly setting bold clean energy goals and challenging the public and private sectors to partner in advancing both economic development and renewable energy solutions. We are governors from different political parties with diverse views on many issues. There is, however, one thing on which we agree. Our states and the nation are moving toward a clean and carbon-free energy future that needs the reliability and resilience provided by the nation’s regional transmission operators. In some states, for example, wind and solar energy meet over 20 percent of electricity demand. Renewable energy’s contribution to the entire nation's electricity supply is likely to exceed 20 percent far sooner than predicted. This remarkable progress in renewable energy development would not have been possible without the leadership of the nation's governors, Congress, Administrations from both parties, and regional transmission operators. States have the right to choose their mix of energy-generating resources and policies. The challenge we face today is to find a way to ensure the compatibility of individual state energy policies and PJM’s reserve power market, while also meeting the need for reliable electricity. -

May 1, 2020 Fuel Waiver Concerning Summer Gasoline Dear Governors

March 27, 2020 Re: May 1, 2020 Fuel Waiver Concerning Summer Gasoline Dear Governors and Mayor Bowser: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, in consultation with the U.S. Department of Energy and representatives of the various states, has been working to evaluate fuel supply problems caused by the novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Based on this evaluation, the EPA has determined, and DOE concurs, that it is necessary to waive certain federal fuel standards under the Clean Air Act (CAA) to minimize or prevent the disruption of an adequate supply of gasoline throughout the United States. This waiver only applies to the federal fuel standards. Regulated parties must continue to comply with any applicable state or local requirements, or restrictions related to this matter, unless waived by the appropriate authorities. As you know, regulations promulgated under the CAA require the use of low volatility gasoline during the summer months in order to limit the formation of ozone pollution. The regulations requiring the use of low volatility conventional gasoline during the summer season are found at 40 C.F.R. § 80.27 and in certain State Implementation Plans (SIPs). See 40 C.F.R. § 80.27 and https://www.epa.gov/gasoline-standards/gasoline-reid-vapor-pressure#table. The regulations requiring the use of low volatility reformulated gasoline (RFG) are found at 40 C.F.R. § 80.78 and in certain SIPs. The RFG regulations at 40 C.F.R. § 80.78(a)(7) also prohibit any person from combining any reformulated blendstock for oxygenate blending (RBOB) with any other gasoline, blendstock, or oxygenate, except for the oxygenate of the type and amount specified by the refiner that produced the RBOB. -

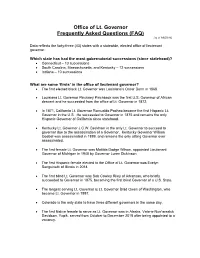

Office of Lt. Governor Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) (As of 6/6/2019)

Office of Lt. Governor Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) (as of 6/6/2019) Data reflects the forty-three (43) states with a statewide, elected office of lieutenant governor. Which state has had the most gubernatorial successions (since statehood)? • Connecticut – 13 successions • South Carolina, Massachusetts, and Kentucky – 12 successions • Indiana – 10 successions What are some ‘firsts’ in the office of lieutenant governor? • The first elected black Lt. Governor was Louisiana’s Oscar Dunn in 1868. • Louisiana Lt. Governor Pinckney Pinchback was the first U.S. Governor of African descent and he succeeded from the office of Lt. Governor in 1872. • In 1871, California Lt. Governor Romualdo Pacheo became the first Hispanic Lt. Governor in the U.S. He succeeded to Governor in 1875 and remains the only Hispanic Governor of California since statehood. • Kentucky Lt. Governor J.C.W. Beckham is the only Lt. Governor to succeed to governor due to the assassination of a Governor. Kentucky Governor William Goebel was assassinated in 1899, and remains the only sitting Governor ever assassinated. • The first female Lt. Governor was Matilda Dodge Wilson, appointed Lieutenant Governor of Michigan in 1940 by Governor Luren Dickinson. • The first Hispanic female elected to the Office of Lt. Governor was Evelyn Sanguinetti of Illinois in 2014. • The first blind Lt. Governor was Bob Cowley Riley of Arkansas, who briefly succeeded to Governor in 1975, becoming the first blind Governor of a U.S. State. • The longest serving Lt. Governor is Lt. Governor Brad Owen of Washington, who became Lt. Governor in 1997. • Colorado is the only state to have three different governors in the same day. -

Biden Administration: Cabinet and Staff

Biden Administration: Cabinet and Staff Cabinet Officials—Department Heads Department of Agriculture Tom Vilsack Confirmed President Biden nominated former Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack to reprise his role. President Biden stressed that Secretary Vilsack’s previous experience would allow the nominee to hit the ground running on his first day in office and combat the unprecedented hunger crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Former Secretary Vilsack was unanimously confirmed as Secretary of Agriculture in 2009. Department of Commerce Governor Gina Raimondo Confirmed Gina Raimondo, the Governor of Rhode Island, was confirmed to lead the Department of Commerce. She will be a major player in deciding whether or not to roll back any of the sanctions imposed on Chinese corporations by the former Trump administration. Once considered a potential running-mate for then-candidate Biden, she previously worked as a venture-capital executive and State Treasurer. President Biden also selected Don Graves to serve as Deputy Secretary of Commerce. Department of Defense Retired General Lloyd Austin Confirmed General Austin is the first Black man in history to helm the Defense Department. He had an easy confirmation process, after both the House of Representatives and Senate passed a waiver allowing the former general to take control of the civilian branch of the military. Before retiring in 2016, General Austin served in the Army for more than 40 years. President Biden nominated Dr. Kathleen Hicks to serve as deputy secretary of defense and Dr. Colin Kahl as under-secretary of defense for policy. 1 Department of Education Dr. Miguel Cardona Confirmed Dr. Miguel Cardona, who previously served as Connecticut’s Education Commissioner, was confirmed as the Secretary of Education.