What Copying Meant to Cézanne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illustrations of Selected Works in the Various National Sections of The

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION libraries 390880106856C A«T FALACr CttNTRAL. MVIIION "«VTH rinKT OFFICIAI ILLUSTRATIONS OF SELECTED WORKS IN THE VARIOUS NATIONAL SECTIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ART WITH COMPLETE LIST OF AWARDS BY THE INTERNATIONAL JURY UNIVERSAL EXPOSITION ST. LOUIS, 1904 WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HALSEY C. IVES, CHIEF OF THE DEPARTMENT DESCRIPTIVE TEXT FOR PAINTINGS BY CHARLES M. KURTZ, Ph.D., ASSISTANT CHIEF DESCRIPTIVE TEXT FOR SCULPTURES BY GEORGE JULIAN ZOLNAY, superintendent of sculpture division Copyr igh r. 1904 BY THE LOUISIANA PURCHASE EXPOSITION COMPANY FOR THE OFFICIAL CATALOGUE COMPANY EXECUTIVE OFFICERS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ART Department ' B’’ of the Division of Exhibits, FREDERICK J. V. SKIFF, Director of Exhibits. HALSEY C. IVES, Chief. CHARLES M. KURTZ, Assistant Chief. GEORGE JULIAN ZOLNAY, Superintendent of the Division of Sculpture. GEORGE CORLISS, Superintendent of Exhibit Records. FREDERIC ALLEN WHITING, Superintendent of the Division of Applied Arts. WILL H. LOW, Superintendent of the Loan Division. WILLIAM HENRY FOX Secretary. INTRODUCTION BY Halsey C. Ives “All passes; art alone enduring stays to us; I lie bust outlasts the throne^ the coin, Tiberius.” A I an early day after the opening of the Exposition, it became evident that there was a large class of visitors made up of students, teachers and others, who desired a more extensive and intimate knowledge of individual works than could be gained from a cursory view, guided by a conventional catalogue. 11 undreds of letters from persons especially interested in acquiring intimate knowledge of the leading char¬ acteristics of the various schools of expression repre¬ sented have been received; indeed, for two months be¬ fore the opening of the department, every mail carried replies to such letters, giving outlines of study, courses of reading, and advice to intending visitors. -

ACP Spire May2019.Pdf

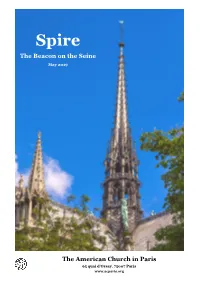

Spire The Beacon on the Seine May 2019 The American Church in Paris 65 quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris www.acparis.org Please help recycle this publication. When you’re through reading it, instead of tossing it in the bin, return it to the Welcome desk or Foyer. In this issue Thoughts from The Rev. Dr. Scott Herr 3 Bible readings for May 4 Spring retreat at Abbaye-Fleury, by Rev. Tim Vance 5 Prayer ministry, by TL Valluy 6 Notre Dame, by Rebecca Brite 7 Alpha success, by Lisa Prevett 9 Body of Christ: What’s up in Paris, by MaryClaire King 10 What’s up in Paris: May event listings, by Karen Albrecht 11 Sunday Atelier Concert Series, by Fred Gramann 12 Silence: The Christian stranger in Japan, by David Jolly 13 Recipe for a successful Easter breakfast, by Mary Hovind 14 The AFCU meets in Paris 15 ACP Taizé Thursdays, by Julia Metcalf 17 ACP Youth Program Concerts, by Sara Barton 19 The Nabis and decoration, by Karen Marin 21 May ACP calendar, by John Newman 22-23 ACP volunteer opportunities 23 The spire of the Notre Dame, as it was. Note the rescued rooster (the so-called “spiritual lightning rod”) and the bronze statues of the apostles, including that of Thomas the Apostle (his back to the viewer), with the features of restorer Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. Read more in our story on page 7. Photo: ©CreativeMarket 2 ACP Spire, May 2019 Thoughts from The Rev. Dr. Scott Herr Senior Pastor Dear Members and Friends of the ACP, Grace, mercy and peace response recognizing that although we are a different “part” to you in these first weeks of the holy catholic Church, nevertheless we are brothers of Eastertide. -

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY of P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS Iwasttr of Fint Girt

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS DISSERTATION SU8(N4ITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIfJIMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iWasttr of fint girt (M. F. A.) SABIRA SULTANA '^tj^^^ Under the supervision of 0\AeM'TCVXIIK. Prof. ASifl^ M. RIZVI Dr. (Mrs) SIRTAJ RlZVl S'foervisor Co-Supei visor DEPARTMENT OF FINE ART ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 Z>J 'Z^ i^^ DS28S5 dedicated to- (H^ 'Parnate ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY CHAIRMAN DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS ALIGARH—202 002 (U.P.), INDIA Dated TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that Sabera Sultana of Master of Fine Art (M.F.A.) has completed her dissertation entitled "AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P.A. RENOIR'S PAINTINGS" under the supervision of Prof. Ashfaq M. Rizvi and co-supervision of Dr. (Mrs.) Sirtaj Rizvi. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work is based on the investigations made, data collected and analysed by her and it has- not been submitted in any other university or Institution for any degree. Mrs. SEEMA JAVED Chairperson m4^ &(Mi/H>e& of Ins^tifHUion/, ^^ui'lc/aace' cm^ eri<>ouruae/riefity: A^ teacAer^ and Me^^ertHs^^r^ o^tAcsy (/Mser{xUlafi/ ^rof. £^fH]^ariimyrio/ar^ tAo las/y UCM^ accuiemto &e^£lan&. ^Co Aasy a€€n/ kuid e/KHc^ tO' ^^M^^ me/ c/arin^ tA& ^r€^b<ir<itlan/ of tAosy c/c&&erla6iafi/ and Aasy cAecAe<l (Ao contents' aMd^yormM/atlan&^ arf^U/ed at in/ t/ie/surn^. 0A. Sirta^ ^tlzai/ ^o-Su^benn&o^ of tAcs/ dissertation/ Au&^^UM</e^m^o If^fi^^ oft/us dissertation/, ^anv l>eAo/den/ to tAem/ IhotA^Jrom tAe/ dee^ o^nu^ l^eut^. -

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection

Cézanne and the Modern: Masterpieces of European Art from the Pearlman Collection Paul Cézanne Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1904–06 (La Montagne Sainte-Victoire) oil on canvas Collection of the Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum TEACHER’S STUDY GUIDE WINTER 2015 Contents Program Information and Goals .................................................................................................................. 3 Background to the Exhibition Cézanne and the Modern ........................................................................... 4 Preparing Your Students: Nudes in Art ....................................................................................................... 5 Artists’ Background ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Modern European Art Movements .............................................................................................................. 8 Pre- and Post-Visit Activities 1. About the Artists ....................................................................................................................... 9 Artist Information Sheet ........................................................................................................ 10 Modern European Art Movements Fact Sheet .................................................................... 12 Student Worksheet ............................................................................................................... -

Edrs Price Descriptors

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 224 EA 005 958 AUTHOR Kohl, Mary TITLE Guide to Selected Art Prints. Using Art Prints in Classrooms. INSTITUTION Oregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Salem. PUB DATE Mar 74 NOTE 43p.; Oregon'ASCD Curriculum Bulletin v28 n322 AVAILABLE FROMOregon Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, P.O. Box 421, Salem, Oregon 9730A, ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 DESCRIPTORS *Art Appreciation; *Art Education; *Art Expression; Color Presentation; Elementary Schools; *Painting; Space; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS Texture ABSTRACT A sequential framework of study, that can be individually and creatively expanded, is provided for the purpose of developing in children understanding of and enjoyment in art. .The guide indicates routes of approach to certain kinds of major art, provides historical and biographical information, clarifies certain fundamentals of art, offers some activities related to the various ,elements, and conveys some continuing enthusiasm for the yonder of art creation. The elements of art--color, line, texture, shape, space, and forms of expression--provide the structure of pictorial organization. All of the pictures recomme ded are accessible tc teachers through illustrations in famil'a art books listed in the bibliography. (Author/MLF) US DEPARTMENT OF HE/ EDUCATION & WELFAS NATIONAL INSTITUTE I EOW:AT ION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEF DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIV e THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIO ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR STATED DO NOT NECESSAR IL SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INS1 EDUCATION POSIT100. OR POL Li Vi CD CO I IP GUIDE TO SELECTED ART PRINTS by Mary Kohl 1 INTRODUCTION TO GUIDE broaden and deepen his understanding and appreciation of art. -

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

The Skin of Van Gogh's Paintings Joris Dik*, Matthias Alfeld, Koen Janssens and Ella Hendriks * Dept

1788 Microsc. Microanal. 17 (Suppl 2), 2011 doi:10.1017/S1431927611009810 © Microscopy Society of America 2011 The Skin of Van Gogh's Paintings Joris Dik*, Matthias Alfeld, Koen Janssens and Ella Hendriks * Dept. of Materials Science, Delft University of Technology, Mekelweg 2, 2628CD, Delft, the Netherlands Just microns below their paint surface lay a wealth of information on Old Master Paintings. Hidden layers can include the underdrawing, the underpainting or compositional alterations by the artist. In addition, the outer surface of a paint layer may have suffered from discoloration. Thus, a look through the paint surface provides a look over the artist’s shoulder, which is crucial in technical art history, conservation issues and authenticity studies. In this contribution I will focus on the degradation mechanism of early modern painting pigments used in the work of Vincent van Gogh. These include pigments such as cadmium yellow and lead chromate yellow. Recent studies [1,2,3] of these pigments have revealed stability problems. Cadmium yellow, or cadmium sulfide, may suffer from photo-oxidation at the utmost surface of the paint film, resulting in the formation of colorless cadmium sulfate hydrates. Lead chromate, on the other hand, can be subject to a reduction process, yielding green chrome oxide at the visible surface. Obviously, such effects can seriously disfigure the original appearance of Van Gogh's oeuvre, as will be shown by a number of case studies. The degradation mechanisms were revealed using an elaborate analytical campaign, mostly involving cross-sections from the original artwork, as well as model paintings that had been aged artificially. -

Site/Non-Site Explores the Relationship Between the Two Genres Which the Master of Aix-En- Provence Cultivated with the Same Passion: Landscapes and Still Lifes

site / non-site CÉZANNE site / non-site Guillermo Solana Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid February 4 – May 18, 2014 Fundación Colección Acknowledgements Thyssen-Bornemisza Board of Trustees President The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Hervé Irien José Ignacio Wert Ortega wishes to thank the following people Philipp Kaiser who have contributed decisively with Samuel Keller Vice-President their collaboration to making this Brian Kennedy Baroness Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza exhibition a reality: Udo Kittelmann Board Members María Alonso Perrine Le Blan HRH the Infanta Doña Pilar de Irina Antonova Ellen Lee Borbón Richard Armstrong Arnold L. Lehman José María Lassalle Ruiz László Baán Christophe Leribault Fernando Benzo Sáinz Mr. and Mrs. Barron U. Kidd Marina Loshak Marta Fernández Currás Graham W. J. Beal Glenn D. Lowry HIRH Archduchess Francesca von Christoph Becker Akiko Mabuchi Habsburg-Lothringen Jean-Yves Marin Miguel Klingenberg Richard Benefield Fred Bidwell Marc Mayer Miguel Satrústegui Gil-Delgado Mary G. Morton Isidre Fainé Casas Daniel Birnbaum Nathalie Bondil Pia Müller-Tamm Rodrigo de Rato y Figaredo Isabella Nilsson María de Corral López-Dóriga Michael Brand Thomas P. Campbell Nils Ohlsen Artistic Director Michael Clarke Eriko Osaka Guillermo Solana Caroline Collier Nicholas Penny Marcus Dekiert Ann Philbin Managing Director Lionel Pissarro Evelio Acevedo Philipp Demandt Jean Edmonson Christine Poullain Secretary Bernard Fibicher Earl A. Powell III Carmen Castañón Jiménez Gerhard Finckh HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco Giancarlo Forestieri William Robinson Honorary Director Marsha Rojas Tomàs Llorens David Franklin Matthias Frehner Alejandra Rossetti Peter Frei Katy Rothkopf Isabel García-Comas Klaus Albrecht Schröder María García Yelo Dieter Schwarz Léonard Gianadda Sir Nicholas Serota Karin van Gilst Esperanza Sobrino Belén Giráldez Nancy Spector Claudine Godts Maija Tanninen-Mattila Ann Goldstein Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza Michael Govan Charles L. -

Key to the People and Art in Samuel F. B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre

15 21 26 2 13 4 8 32 35 22 5 16 27 14 33 1 9 6 23 17 28 34 3 36 7 10 24 18 29 39 C 19 31 11 12 G 20 25 30 38 37 40 D A F E H B Key to the People and Art in Samuel F. B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre In an effort to educate his American audience, Samuel Morse published Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures. Thirty-seven in Number, from the Most Celebrated Masters, Copied into the “Gallery of the Louvre” (New York, 1833). The updated version of Morse’s key to the pictures presented here reflects current scholarship. Although Morse never identified the people represented in his painting, this key includes the possible identities of some of them. Exiting the gallery are a woman and little girl dressed in provincial costumes, suggesting the broad appeal of the Louvre and the educational benefits it afforded. PEOPLE 19. Paolo Caliari, known as Veronese (1528–1588, Italian), Christ Carrying A. Samuel F. B. Morse the Cross B. Susan Walker Morse, daughter of Morse 20. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519, Italian), Mona Lisa C. James Fenimore Cooper, author and friend of Morse 21. Antonio Allegri, known as Correggio (c. 1489?–1534, Italian), Mystic D. Susan DeLancy Fenimore Cooper Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria E. Susan Fenimore Cooper, daughter of James and Susan DeLancy 22. Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640, Flemish), Lot and His Family Fleeing Fenimore Cooper Sodom F. Richard W. Habersham, artist and Morse’s roommate in Paris 23. -

Claude Monet : Seasons and Moments by William C

Claude Monet : seasons and moments By William C. Seitz Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1960 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with the Los Angeles County Museum: Distributed by Doubleday & Co. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2842 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The Museum of Modern Art, New York Seasons and Moments 64 pages, 50 illustrations (9 in color) $ 3.50 ''Mliili ^ 1* " CLAUDE MONET: Seasons and Moments LIBRARY by William C. Seitz Museumof MotfwnArt ARCHIVE Claude Monet was the purest and most characteristic master of Impressionism. The fundamental principle of his art was a new, wholly perceptual observation of the most fleeting aspects of nature — of moving clouds and water, sun and shadow, rain and snow, mist and fog, dawn and sunset. Over a period of almost seventy years, from the late 1850s to his death in 1926, Monet must have pro duced close to 3,000 paintings, the vast majority of which were landscapes, seascapes, and river scenes. As his involvement with nature became more com plete, he turned from general representations of season and light to paint more specific, momentary, and transitory effects of weather and atmosphere. Late in the seventies he began to repeat his subjects at different seasons of the year or moments of the day, and in the nineties this became a regular procedure that resulted in his well-known "series " — Haystacks, Poplars, Cathedrals, Views of the Thames, Water ERRATA Lilies, etc. -

Un Musée Révolutionnaire Le Musée Des Monuments Français D’Alexandre Lenoir

Un Musée révolutionnaire Le musée des Monuments français d’Alexandre Lenoir Musée du Louvre Églises St-Eustache / St-Roch / St-Sulpice Le musée des Monuments français, The Museum of French Monuments, aujourd’hui tombé dans l’oubli, connut now forgotten, had during the French sous la Révolution française un destin Revolution an exceptional destiny. exceptionnel. Located close to Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Situé non loin de Saint-Germain-des-Prés, in the convent of the Petits-Augustins, dans le couvent des Petits-Augustins, le musée ouvre ses portes en 1795 grâce the museum opens its doors in 1795 thanks à l’engagement d’un jeune peintre. to the commitment of a young painter. Soucieux de préserver les œuvres As he wanted to preserve the confiscated saisies dans les églises, suite à artworks in churches, Alexandre Lenoir la confiscation des biens du clergé, (1761-1839) contributed to preserve many Alexandre Lenoir (1761-1839) contribue tombs and statues. The exhibition, in a à préserver de nombreux tombeaux et chronological, scientific and romantic course, statues de culte. La présentation knew a huge success with the public from all de ces vestiges, selon un parcours over Europe. chronologique, savant et romantique, connait un immense succès auprès At the closing of the museum in 1816, its du public qui accourt de toute l’Europe pour le visiter. collections are scattered: artworks are sent to the Louvre or are replaced in the churches of À la fermeture du musée en 1816, ses Paris. Some find their original building, others, collections sont dispersées : les œuvres often after the destruction of their monastery sont envoyées au Musée du Louvre ou or church, are assigned to remaining places.