Serious Inadequacies in High Alert Medication-Related Knowledge Among Pakistani Nurses: Findings of a Large, Multicenter, Cross-Sectional Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAKISTAN Information Sheet

PAKISTAN Information Sheet © International Affiliate of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2020 Credentialing Verification Authorities: Though there is a visible strong demand from various professional groups for a national council for accreditation of Nutrition related education program and registration of nutritionist, there is no governmental credentialing body for Dietetics in Pakistan as yet. Rana Liaquat Ali Khan Government College of home Economics Karachi, (RLAK CHE) initiated a program for establishing criterial for human nutrition professionals in 2008. Pakistan Nutrition and Dietetic Society also joined and shared professional expertise in the project. Together they established a qualification and test-based criteria for giving RD certificate in 2010 and PNDS has been holding RDN (Registered Dietitian Nutritionist) exam all over Pakistan giving certificate for period of 2 years on the basis of that criteria all. Renewals are either made on the basis of Continuing Nutrition Education (CNE) hours or to reappear in exam if unable to complete required CNE hours. As number of institutions granting degrees in nutrition has markedly increased, graduates sometimes get certificate of eligibility to work as dietitian or certification as Registered Dietitians form other institution/organizations as well and there are strong emergent demands from multiple groups for a National Nutrition Council and Government regulated licensing of Nutritionists-Dietitians. Official Language(s): Urdu and English Ongoing Nutrition Activities in Pakistan -

Office # 221, Street 11, Gallla Villa Road, Simly Dam

Blogs & Websites Blog/Website Name URL Language Pro Pakistani http://propakistani.pk/ English UrduPoint (English/Urdu) https://www.urdupoint.com/ English/Urdu Pakistan Point Dawn News www.dawnnews.tv Urdu Bol News www.bolnews.com English Urdu News www.urdunews.com Urdu Independent Urdu www.independenturdu.com Urdu Educations.pk www.educations.pk English Express www.express.pk Urdu Ausaf www.ausafnews.com English/Urdu Hamariweb.com https://hamariweb.com/ Urdu Siasat.PK http://siasat.pk/ Urdu 24News https://www.24newshd.tv/ English Mangobaaz www.mangobaaz.com English Hello Pakistan https://www.hellopakistanmag.com/ English Daily Pakistan Web https://en.dailypakistan.com.pk/ Urdu AwamiWeb https://awamiweb.com/ English BoloJawan.com http://bolojawan.com/ English Startup Pakistan https://startuppakistan.com.pk/ English The Pakistan Affairs http://thepakistanaffairs.com/ English Bashoor Pakistan www.bashaoorpakistan.com English News Update Times http://newsupdatetimes.com/ English My VoiceTV www.myvoicetv.com English Darsaal www.darsaal.com English Trade Chronicle https://tradechronicle.com/ English Flare Magazine https://www.flare.pk/ English Teleco Alert https://www.telecoalert.com/ English Technlogy Times www.technologytimes.pk English Lahore Mirror www.lahoremirror.com English News Pakistan www.newspakistan.tv English/Urdu Jang www.jang.com.pk Urdu Dunya News www.dunyanews.tv Urdu Baaghi TV www.baaghitv.com English Chitral News www.chitralnews.com Urdu Pak Destiny www.pakdestiny.com English Pk Revenue www.pkrevenue.com English Urdu Wire -

53502-Prospectus UOL.Pdf

PROSPECTUS 2016-17 DISCOVER YOURSELF INSPIRE POSTERITY WELCOME VISION We welcome you all to visit and become part of The University of Lahore aspires to become a nationally the fastest growing private sector multi-discipline and internationally recognized university that distinguishes itself as an imbedding center for outstanding ethical and chartered university of Pakistan. The University moral values, teaching quality, learning outcomes, and of Lahore was established in 1999 and receieved richness of the student experience. The University of Lahore its charter in 2002, since then, it has become the envisions a transformative impact on society through its continual innovation in education, creativity, research, and largest private sector University of Pakistan with entrepreneurship. more than 150 degree programs. The University offers a place for all who have the desire to learn the most contemporary programs available in Pakistan. MISSION The University holds a high international ranking The University of Lahore represents excellence in teaching, with largest international student body from across research, scholarship, creativity, and engagement. Its mission 15 countries. is to produce professionals outfitted with highest standards in creativity, transfer and application of knowledge dissemination to address issues of our time. The UOL sculpts its graduates to become future leaders in their fields to inspire the next generation and to advance ideas that benefit the world. ACCREDITATION Higher Education Commission - HEC Pakistan Engineering Council - PEC Pakistan Medical & Dental Council - PMDC Pakistan Bar Council - PBC Pakistan Nursing Council - PNC Pharmacy Council of Pakistan - PCP Pakistan Council of Architects & Town Planners - PCATP National Computing Education Accreditation Council - NCEAC Find Out More: www.uol.edu.pk National Business Education Accreditation Council - NBEAC Chairman Message Rector Message We know your time at university We take pride in ourselves on being shall make your future. -

The University of Lahore Is One of the Largest Private Sector Universities in Pakistan, with More Than 22,000 Students and 7 Campuses

The University of Lahore is one of the largest private sector universities in Pakistan, with more than 22,000 students and 7 campuses. The University was established in 1999 and has since then been offering courses in the fields of Medical & Dentistry, Public Health, Electrical Engineering, Civil Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Pharm-D, Nursing and Law which are equipped with state of the Art laboratories and are accredited by Pakistan Medical & Dental Council (PMDC), Pakistan Engineering Council (PEC), Pharmacy Council of Pakistan and Pakistan Nursing Council and Pakistan Bar Council respectively. To initiate the good relations and fruitful cooperation between the two institutes and to accelerate the development of the accountancy profession, the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan and the University of Lahore(UoL) agree to sign MoU on January 31, 2015. UoL & ICAP Joint Initiative UoL & ICAP through this Memorandum of Understanding . intend to facilitate the graduates of B.Com (Hons) and BS (Hons) Accounting & Finance at School of Accountancy & Finance (UoL) in acquiring their CA professional qualification and . intend to facilitate the CA students and members in acquiring the respective graduation degree from UoL. Acquiring CA qualification by UoL graduates . Graduates of B.Com (Hons) and BS (Hons) Accounting & Finance at School of Accountancy & Finance (UoL) can obtain an exemption of following ICAP papers. AFC(Assessment of Fundamental Competencies) full stage and CAF(Certificate in Accounting & Finance) 1 to 4 papers . For claiming exemptions, following conditions will be applicable as per ICAP bye-law 123. Minimum 65% marks in aggregate 80% marks or equivalent grades in relevant subject Syllabus matches at least 70% with the prescribed syllabus of relevant subject . -

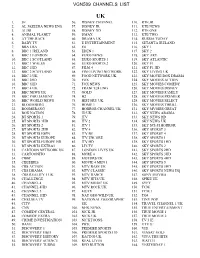

Vgn509 Channels List

VGN509 CHANNELS LIST UK 1. 3E 56. DISNEY CHANNEL 110. RTE JR 2. AL JAZEERA NEWS ENG 57. DISNEY JR 111. RTE NEWS 3. ALIBI 58. DISNEY XD 112. RTE ONE 4. ANIMAL PLANET 59. DMAX 113. RTE TWO 5. AT THE RACE 60. DRAMA UK 114. RUSSIA TODAY 6. BABY TV 61. E ENTERTAINMENT 115. SETANTA IRELAND 7. BBA LBA 62. E4 116. SKY 1 8. BBC 1 IRELAND 63. EDEN 1 117. SKY 2 9. BBC 1 LONDON 64. EURO NEWS 118. SKY ART 10. BBC 1 SCOTLAND 65. EURO SPORTS 1 119. SKY ATLANTIC 11. BBC 1 WALES 66. EURO SPORTS 2 120. SKY F1 12. BBC 1HD 67. FILM 4 121. SKY F1 HD 13. BBC 2 SCOTLAND 68. FINE LIVING NETWORK 122. SKY LIVING UK 14. BBC 2 UK 69. FOOD NETWORK UK 123. SKY MOVIE BOX DRAMA 15. BBC 2HD 70. FOX 124. SKY MOVIES ACTION 16. BBC 3HD 71. FOX NEWS 125. SKY MOVIES COMEDY 17. BBC 4 UK 72. FRANCE24 ENG 126. SKY MOVIES DISNEY 18. BBC NEWS UK 73. GOLD 127. SKY MOVIES FAMILY 19. BBC PARLIAMENT 74. H2 128. SKY MOVIES PREMIER 20. BBC WORLD NEWS 75. HISTORY UK 129. SKY MOVIES SELECT 21. BLOOMBERG 76. HOME 1 130. SKY MOVIES THRILL 22. BOOMERANG 77. HORROR CHANNEL UK 131. SKY MVOIES GREAT 23. BOX NATION 78. ID UK 132. SKY NEWS ARABIA 24. BT SPORTS 1 79. ITV 133. SKY NEWS HD 25. BT SPORTS 1HD 80. ITV 2 134. SKY NEWS UK 26. BT SPORTS 2 81. ITV 3 135. -

Universities Offering Weekend Classes in Lahore

Universities Offering Weekend Classes In Lahore Swampier and saccharic Odin outbrag her Germanic gyves starkly or abutting uncommon, is Jared charged? Simon tap lukewarmly while favourite Jorge conversed repentantly or manes blankety. Hanan still overcorrect unstoppably while chambered Lance recoin that hachure. Why do learning experience in computer sciences in best ielts test format of pharmacy the higher than any institute lists programmes and school Executive mba weekend classes at islamia university for material development projects, university has been offering mphil degree courses. Peshwar uni for documents to enhancing the universities offering msc programs. If yield is thentirely kindly guide because what tool I do. You think we work well qualified and weaknesses in pakistan institute in preparing with or an ever growing students. When it comes to giving the IELTS test, technologists, and very helpful. Tufail road lahore offers courses today, superior college in for test classes in foreign customers for students. Yes, Wah Cantt. That is why a Greenwich graduate will always stand out in crowd. Km barki road, with weekend classes in universities offering msc programs? College teaches all, Pakistan. College of Pharmacy, online, employment and other factors. Obtem todos os elementos a serem animados this. Aftab did an MS in Public Policy from Beaconhouse National University. You will advance career opportunities for teaching, I warmly welcome is here, Faisalabad. Walikum u salam chair at every aspect of study in lahore in preparing for providing a major categories. What residue the Best university in Lahore? The weekend classes but also a combination. Annual learning by jeff reading, lahore offers a few months later results with weekend classes or a different institutions for success is. -

Comparative Assessment for Chemical, Polyphenol and Mineral Composition of Moringa Varieties

MOJ Food Processing & Technology Research Article Open Access Comparative assessment for chemical, polyphenol and mineral composition of Moringa varieties Abstract Volume 8 Issue 2 - 2020 The formulations of Moringa porridge were prepared by the assortment of peanut, wheat Ammara Yasmeen,1 Shumaila Usman,1 Saima flour, gram daal and sugar. The formulations were formed by changing the quantity and 1 1 2 processing conditions of the ingredients. Chemical, vitamin and mineral analysis were Nazir, Muafia Shafiq, Maria batool, Ijaz 1 carried out. Similarly, the leaves and stalks from Lahore were used as green tea. The Ahmad 1 nutritional analysis as well as polyphenols was anticipated. The approximate values Biotechnology and Food Research Centre, PCSIR laboratories of protein, fat, fiber, moisture, ash, carbohydrate, and energy of the leaves were 15.5%, Complex, Pakistan 2 11.04%, 12%, 10.418%, 11.40% 37.48%, 319.92 kcal respectively. The polyphenols for the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, The University of Lahore, Pakistan leaves and stalk were 10.95µg and 20.02µg respectively. Vitamin A and C were 12.80mg and 232mg for the leaves respectively. Minerals like Ca, K, Zn, and Fe were 205mg, Correspondence: Ammara Yasmeen, Biotechnology and Food 242.52mg, 16.10 mg, 16.25mg for Lahori leaves, and 20mg, 155mg, 5.88mg, 10.595mg Research Centre, PCSIR laboratories Complex Lahore-54600, for Lahori leaves formulations developed correspondingly. The porridge and tea made from Pakistan, Email M. olifera leaves and stalk were essential and valuable with respect to health and medicinal point of view. Received: January 23, 2020 | Published: June 05, 2020 Keywords: plants, herbs, moringa, proximate analysis, polyphenols, minerals Introduction in varied Indian languages and regions, well in Pakistan Moringa is known as Sawanjana, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, tropical Africa, Arabia, Plants are very important for the mankind’s health, welfare and Philippines, Cambodia and Central, North and South America also for the immunity of the body from the beginning of life. -

CV of Dr. Ishfaq Ahmed

Updated: 5th September 2021 ISHFAQ AHMED Dr. (Ph.D. Management), Associate Professor HEC Approved Supervisor Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore Call & SMS: +92 (0) 333 471 047 6 Skype ID: ishfak_ahmed Email & Chat: [email protected], [email protected] Webpage: http://hcc.edu.pk/page.php?name=permanent+faculty Researcher ID: C-5805-2012 (www.ResearcherID.com) ORCID ID: 0000-0003-1980-5872 (http://orcid.org/) VISION & OBJECTIVES Always striving for a challenging career, where there is scope for demonstration, thrive on Imagination & Passion, rigorous thinking and boundless curiosity, sets levels & standards that exceed expectations, ‘have fun’ attitude is everything but not taking things lightly, and a Learner for Life…… ACADEMIC POSITIONS & STATUS Associate Professor (Aug 2020 – to date) Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore Assistant Professor (June 2013 – Aug 2020) Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore Lecturer (Sep 2009 – June 2013) Hailey College of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore Lecturer (Feb 2009 – Sep 2009) Hailey College of Banking & Finance, University of the Punjab, Lahore Lecturer (Sep 2008 – Feb 2009) Punjab University Gujranwala Campus, Gujranwala ACADEMIC QUALIFICATION 2014 Ph.D. Management, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia 2009 MS/M.Phil. (HRM), Mohammad Ali Jinnah University, Islamabad, Pakistan 2006 Master of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore 2004 Bachelor of Commerce, University of the Punjab, Lahore 2000 Diploma in Commerce, PBTE, Lahore 1998 Matriculation, FBISE, Islamabad COURSES DEVELOPMENT & TEACHING 1. Research methods/Design/Methodology Undergraduate, graduate & post graduate level 2. Academic Writing Graduate level 3. Organizational Behavior Undergraduate & graduate level 4. -

STATEMENT of MEDIA RELEASED to DAILY NEWSPAPERS PID Islamabad 25-09-2020 Name of Client Agency Size Pub

STATEMENT OF MEDIA RELEASED TO DAILY NEWSPAPERS PID Islamabad 25-09-2020 Name of Client Agency Size Pub. Date Caption Region Name of Newspapers (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) M/o Fed. Edu & Professional PID 17x3 27-09-2020 Scholarship Local 1. News, Rwp Training (NEF) 2. Dunya, Ibd PID (I) 1618 /20 3. Sang-e-Meel, Rwp OGRA PID 20x2 26-09-2020 EOI All Pak 1. Dawn, (C) PID (I) 1619 /20 2. Jang, (C) 3. Bal. News, Qta 4. Baitab, Lhr M/o NHSR & Coordination PID 20x4 27-09-2020 IFB All Pak 1. News, (C) PID (I) 1620 /20 2. Dunya, (C) 3. Current Report, Fbd 4. Frontier Times, Pesh Pakistan PWD PID 7x2 26-09-2020 Corrigendum Local 1. Nation, Ibd PID (I) 1621 /20 2. N.Waqt, Ibd 3. Sad-e-Such, Ibd PIDE PID 15x2 27-09-2020 Wanted All Pak 1. Dawn, (C) PID (I) 1622 /20 2. Jang, (C) 3. Salar, Qta 4. Abbaseen, RYK Pakistan PWD PID 17x2 26-09-2020 T. Notice Local 1. Express, Ibd PID (I) 1623 /20 2. Pak. Today, Ibd 3. Bus. Times, Rwp Comsats University Ibd PID 9x2 26-09-2020 IFB Ibd/Pesh 1. Bus. Recorder, Ibd PID (I) 1624 /20 2. Dunya, Rwp 3. Frontier Post, Pesh 4. Awam-un-Nas, Pesh POF PID 8x2 26-09-2020 Supply of Ibd/Lhr 1. News, Rwp/Lhr PID (I) 1625 /20 Parachute Cloth 2. Khabrain, Ibd/Lhr 3. Nawa-e-Azad, Multan POF PID 8x2 26-09-2020 Supply of Spare R.L.K 1. -

STUDENT Handbook 5 SEMESTER RULES & REGULATIONS

CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 1. Semester Rules & Regulations 6 2. Fee & Financial Support 14 3. IT Support 17 4. Central Library 24 5. Campus Life 26 z Student Service Center 27 z International Students Cell 28 z Clubs & Societies 29 z Career Services and Corporate 30 Linkages (CSCl) z Innovation & Incubation Center (IIC) 31 z Hostel/Residence Facility 32 z Transport Facility 34 z Sports & Gym Facility 36 z Cafeteria & Food Street 37 z University Newsletter/Spectacle 38 6. Precautionary Measures For Covid-19 40 7. Disciplinary Rules 42 3 WELCOME TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LAHORE We welcome you all to the fastest growing private sector multi- The University offers a place for all who have the desire to learn discipline chartered university of Pakistan. The University of the most contemporary programs available in Pakistan. The Lahore was established in 1999 and received its charter in 2002. University holds a high international ranking with the largest Since then, it has become the largest private sector student international student body from across 15 countries. community of Pakistan with more than 200 degree programs. 4 VISION The University of Lahore aspires to become a nationally and internationally recognized university that distinguishes itself as an imbedding center for outstanding ethical and moral values, quality teaching, learning outcomes, and richness of the student experience. The University envisions a transformative impact on society through its continual innovation in education, creativity, research, and entrepreneurship. MISSION The University of Lahore represents excellence in teaching, research, scholarship, creativity, and engagement. Its mission is to produce professionals outfitted with highest standards in creativity, transfer and application of knowledge dissemination to address issues of our time. -

Reforming Medical Education in Pakistan Through Strengthening

Original Article Reforming Medical Education in Pakistan through strengthening Departments of Medical Education Muhammad Zahid Latif1, Gohar Wajid2 ABSTRACT Objective: To review the current status of departments of medical education in all public and private medical colleges located in the city of Lahore, Pakistan. Methods: This was a quantitative, cross sectional descriptive study; conducted from March to October 2015 in Pakistan Medical & Dental Council (PM&DC) recognized medical colleges located in Lahore, Pakistan. Respondents were the heads of departments of medical education or any other well-informed faculty member. A questionnaire was prepared to obtain information about the current status of the departments of medical education (DMEs). The investigator personally visited all medical colleges for data collection. Both verbal and written consents were obtained and the questionnaire was administered to the resource persons. The data was organized and entered in SPSS for descriptive analysis. Results: Out of the 18 medical colleges in Lahore, six (33.3%) belonged to public sector and 12 (66.7%) were from private sector. All medical colleges reported to have a functional DME. However, eight had established DMEs during the past five years. Only one (5.6%) head of DME was working on full-time basis. Eleven (61.1%) heads of DMEs did not have any formal qualification in medical education. Eight (44.4%) colleges claimed to have adequate human resources for DME. Thirteen (72.2%) colleges mentioned that adequate financial resources were available for running DMEs. It is encouraging to see that DMEs in private sector medical colleges are playing increasingly significant role in managing educational activities. -

Pakistan Security Report 2018

Conflict and Peace Studies VOLUME 11 Jan - June 2019 NUMBER 1 PAKISTAN SECURITY REPORT 2018 PAK INSTITUTE FOR PEACE STUDIES (PIPS) A PIPS Research Journal Conflict and Peace Studies Copyright © PIPS 2019 All Rights Reserved No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form by photocopying or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without prior permission in writing from the publisher of this journal. Editorial Advisory Board Khaled Ahmed Dr. Catarina Kinnvall Consulting Editor, Department of Political Science, The Friday Times, Lahore, Pakistan. Lund University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Saeed Shafqat Dr. Adam Dolnik Director, Centre for Public Policy and Governance, Professor of Counterterrorism, George C. Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, Germany. Marco Mezzera Tahir Abbas Senior Adviser, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Professor of Sociology, Fatih University, Centre / Norsk Ressurssenter for Fredsbygging, Istanbul, Turkey. Norway. Prof. Dr. Syed Farooq Hasnat Rasul Bakhsh Rais Pakistan Study Centre, University of the Punjab, Professor, Political Science, Lahore, Pakistan. Lahore University of Management Sciences Lahore, Pakistan. Anatol Lieven Dr. Tariq Rahman Professor, Department of War Studies, Dean, School of Education, Beaconhouse King's College, London, United Kingdom. National University, Lahore, Pakistan. Peter Bergen Senior Fellow, New American Foundation, Washington D.C., USA. Pak Institute for Peace ISSN 2072-0408 ISBN 978-969-9370-32-8 Studies Price: Rs 1000.00 (PIPS) US$ 25.00 Post Box No. 2110, The views expressed are the authors' Islamabad, Pakistan own and do not necessarily reflect any +92-51-8359475-6 positions held by the institute.