Boudoron, an Athenian Fort on Salamis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ship Construct

NOTES ON SALAMlNlAN HARBOURS Kara TOUTO &ur1 ZaAapiq vrjooq ~airroAlq ~aiAlprj v. SKY LAX Introduction My contribution' to this Third International Symposium on "Ship Construction in Antiquity" aims at giving us the chance to visit some of the ancient harbours of Salamis, land of King Ajax and birthplace of Euripides, an island favoured by Geography to be &uAip&voq(well-harboured), not 6uaoppoq vauaiv, as the ancient Greeks would have said. Among the bigger islands of the Saronic Gulf, Salamis, with an area of 93.5 km2, lies nearest to Attica. Its fame derives mainly from the great sea-battle that tookplace in the historic Straits in 480 BC. Yet, that naval battle, however crucial for Greek History,was one of many events in a long and at times turbulent Salaminian history in which ships and seamanship, harbours and sea-communication played a major role. The nautical tradition is still very much in evidence in Salamis today. A substantial part of the income of many of the modern Salaminians derives from activities associated with the functioning of the Naustathmos i.e. the Arsenal of the Greek Fleet in the northeastern part of the island and of a sizeable fleet of fishing boats harboured at Koulouri, the island's capital; and also with the existence of a series of small and medium-size shipyards and ship-repair units around the Bay of Ambelaki in the eastern part of the island and at Perama on the opposite Attic coast, which is linked to Salamis by ferry. YANNOS LOLOS TROPlS 111 As its title suggests, my paper is acompilation of working notes and observations on Salaminian harbours made during recent field research for a larger project concerning Prehistoric Salamis with particular reference to its southern part2, a project on which I have been fortunate to embark in collaboration with Professor Demetrios I. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

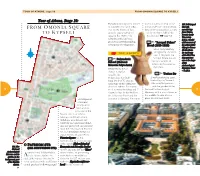

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Networking UNDERGROUND Archaeological and Cultural Sites: the CASE of the Athens Metro

ing”. Indeed, since that time, the archaeological NETWORKING UNDERGROUND treasures found in other underground spaces are very often displayed in situ and in continu- ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND ity with the cultural and archaeological spaces of the surface (e.g. in the building of the Central CULTURAL SITES: THE CASE Bank of Greece). In this context, the present paper presents OF THE ATHENS METRO the case of the Athens Metro and the way that this common use of the underground space can have an alternative, more sophisticated use, Marilena Papageorgiou which can also serve to enhance the city’s iden- tity. Furthermore, the case aims to discuss the challenges for Greek urban planners regarding the way that the underground space of Greece, so rich in archaeological artifacts, can become part of an integrated and holistic spatial plan- INTRODUCTION: THE USE OF UNDERGROUND SPACE IN GREECE ning process. Greece is a country that doesn’t have a very long tradition either in building high ATHENS IN LAYERS or in using its underground space for city development – and/or other – purposes. In fact, in Greece, every construction activity that requires digging, boring or tun- Key issues for the Athens neling (public works, private building construction etc) is likely to encounter an- Metropolitan Area tiquities even at a shallow depth. Usually, when that occurs, the archaeological 1 · Central Athens 5 · Piraeus authorities of the Ministry of Culture – in accordance with the Greek Archaeologi- Since 1833, Athens has been the capital city of 2 · South Athens 6 · Islands 3 · North Athens 7 · East Attica 54 cal Law 3028 - immediately stop the work and start to survey the area of interest. -

Generation 2.0 for Rights, Equality & Diversity

Generation 2.0 for Rights, Equality & Diversity Intercultural Mediation, Interpreting and Consultation Services in Decentralised Administration Immigration Office Athens A (IO A) January 2014 - now On 1st January 2014, the One Stop Shop was launched and all the services issuing and renewing residence permits for immigrants in Greece were moved from the municipalities to Decentralised Administrations. Namely, the 66 Attica municipalities were shared between 4 Immigration Offices of the Attic Decentralised Administration. a) Immigration Office for Athens A with territorial jurisdiction over residents of the Municipality of Athens, Address: Salaminias 2 & Petrou Ralli, Athens 118 55 b) Immigration Office for Central Athens and West Attica, with territorial jurisdiction over residents of the following Municipalities; i) Central Athens: Filadelfeia-Chalkidona, Galatsi, Zografou, Kaisariani, Vyronas, Ilioupoli, Dafni-Ymittos, ii) West Athens: Aigaleo Peristeri, Petroupoli, Chaidari, Agia Varvara, Ilion, Agioi Anargyroi- Kamatero, and iii) West Attica: Aspropyrgos, Eleusis (Eleusis-Magoula) Mandra- Eidyllia (Mandra - Vilia - Oinoi - Erythres), Megara (Megara-Nea Peramos), Fyli (Ano Liosia - Fyli - Zefyri). Address: Salaminias 2 & Petrou Ralli, Athens 118 55 c) Immigration Office for North Athens and East Attica with territorial jurisdiction over residents of the following Municipalities; i) North Athens: Penteli, Kifisia-Nea Erythraia, Metamorfosi, Lykovrysi-Pefki, Amarousio, Fiothei-Psychiko, Papagou- Cholargos, Irakleio, Nea Ionia, Vrilissia, -

Iconography of the Gorgons on Temple Decoration in Sicily and Western Greece

ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE By Katrina Marie Heller Submitted to the Faculty of The Archaeological Studies Program Department of Sociology and Archaeology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science University of Wisconsin-La Crosse 2010 Copyright 2010 by Katrina Marie Heller All Rights Reserved ii ICONOGRAPHY OF THE GORGONS ON TEMPLE DECORATION IN SICILY AND WESTERN GREECE Katrina Marie Heller, B.S. University of Wisconsin - La Crosse, 2010 This paper provides a concise analysis of the Gorgon image as it has been featured on temples throughout the Greek world. The Gorgons, also known as Medusa and her two sisters, were common decorative motifs on temples beginning in the eighth century B.C. and reaching their peak of popularity in the sixth century B.C. Their image has been found to decorate various parts of the temple across Sicily, Southern Italy, Crete, and the Greek mainland. By analyzing the city in which the image was found, where on the temple the Gorgon was depicted, as well as stylistic variations, significant differences in these images were identified. While many of the Gorgon icons were used simply as decoration, others, such as those used as antefixes or in pediments may have been utilized as apotropaic devices to ward off evil. iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my family and friends for all of their encouragement throughout this project. A special thanks to my parents, Kathy and Gary Heller, who constantly support me in all I do. I need to thank Dr Jim Theler and Dr Christine Hippert for all of the assistance they have provided over the past year, not only for this project but also for their help and interest in my academic future. -

Presumed Large-Scale Exploitation and Marketing of Protected Marine Shelled Molluscs (Greece)

Strasbourg, 11 September 2020 T-PVS/Files(2020)5 [files05e_2020.docx] CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF EUROPEAN WILDLIFE AND NATURAL HABITATS Standing Committee 40th meeting Strasbourg, 1-4 December 2020 __________ Complaints on stand-by Presumed large-scale exploitation and marketing of protected marine shelled molluscs (Greece) - REPORT BY THE COMPLAINANT - Document prepared by the University of the Aegean This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. Ce document ne sera plus distribué en réunion. Prière de vous munir de cet exemplaire. T-PVS/Files(2020)5 2 - August 2020 – The situation remains the same since our previous report. Nevertheless, instead of a report, I would like to submit a recently published paper by Italian colleagues (attached), which studied the illegal date mussel fishery in the Mediterranean, and highlighted that Greece is the 'champion' of poaching (see e.g. Fig. 6). I have to notice that my complaint, which dates back to 2014, has not led so far to any effective measures by Greece to confront the issue. The stated actions by the government remain ineffective (e.g. public awareness through an e-leaflet in the ministry's webpage with low outreach) or a 'wish list' (e.g. the enhancement of controls). Since the destructive date mussel fishery remains and the pressure on coastal ecosystems increases, I would like to ask you for more drastic actions and pressure on the Greek government. Sincerely, Prof. Stelios Katsanevakis, PhD University of the Aegean Department of Marine Sciences -

Megara's Harbours

Chapter 4 KLAUS FREITAG – Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule, Aachen [email protected] With and Without You: Megara’s Harbours The main question that will be addressed in this article is whether and how the harbour towns of the Megarid constituted local places in their own right. Exploring the entangled history of the polis Megara and its ports, this paper also points to the complexities behind scholarly approximations to the local horizon of an ancient Greek city-state. Population Figures and Territory Sizes The estimated population of Megara in the fifth century was c. 40,000. 1 In some calculations this figure includes a high number of slaves, c. 15,000 (cf. Plut. Demetr. 9).2 In the Hellenistic period, the number appears to have been significantly smaller. We note that, while 3,000 Megarian hoplites had fought at Plataia in 479 BCE, in 279 BCE, Megara only sent 400 hoplites to Thermopylai to face the Galatian Invasion. 3 This reduction might have been due, in part, to the secession of Pagai and Aigosthena. The epigraphic evidence from Aigosthena, discussed above, informs the estimation of population figures there, at least in the third century BCE. According to Beloch, the 1 Legon 1981: 23, based on estimations of agricultural capacities. 2 Legon 2005: 463. 3 Paus. 10.20.4; cf. Legon 1981: 301, who doubts that this was the full contingent. Plataia: Hdt. 9.28. Hans Beck and Philip J. Smith (editors). Megarian Moments. The Local World of an Ancient Greek City-State. Teiresias Supplements Online, Volume 1. 2018: 97-127. -

The Greek Suffix -Ozos a Case Study in Loan Suffixation

Journal of Greek Linguistics 16 (2016) 232–265 brill.com/jgl The Greek suffix -ozos A Case Study in Loan Suffixation Georgia Katsouda Research Centre for Modern Greek Dialects, Academy of Athens [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a morphological analysis of the borrowed derivational suffix -όζος [ózos], used in both a number of Modern Greek (MGr) dialects and in Standard Mod- ern Greek (SMGr). It draws on an extensive corpus to examine the suffix from both a synchronic and a diachronic perspective. Our diachronic analysis emphasizes the geo- graphical distribution, the etymological provenance of the suffix, and the loan accom- modation strategies employed in various MGr dialects, thus providing some interest- ing etymological findings regarding the lexical stock of Modern Greek (Standard and dialects). Our synchronic analysis focuses on the stem categories with which the suffix combines and accounts for the phonological, morphological, and syntactic constraints that function during the derivational process. Keywords loanword – loan suffixation – borrowable – donor language – recipient language – accommodation strategy – constraint 1 Introduction This paper provides a morphological analysis of the borrowed derivational suffix -όζος [ózos], which has not until now been systematically investigated. The suffix is used in a number of Modern Greek (MGr) dialects, mainly to form adjectives, as shown in (1): © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2016 | doi: 10.1163/15699846-01602003 Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 03:18:14PM via free access the greek suffix -ozos 233 (1) a. σωματόζος [somatózos] Myconos, Paros, Zakynthos ‘stout’ b. αιματόζος [ematózos] Kythira ‘scarlet’ Here, in the present article, we draw on an extensive corpus to examine the suffix -όζος [ózos] from both a synchronic and a diachronic perspective. -

Port Environmental Risk Assessment, Case Study: Port of Perama

International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887) Volume 178 – No. 24, June 2019 Port Environmental Risk Assessment, Case Study: Port of Perama D. Lagoudaki N. Nikitakos D. Papachristos Dept. of Industrial Design and Dpt. of Shipping Trade & Transport, Dept. Industrial Engineering and Production Engineering University of University of Aegean Production West Attica Greece University of West Attica Athens, Greece Greece ABSTRACT 2. ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTION Much of the world prosperity today has been produced or FROM PORT FACILITIES facilitated by seaports and their associated activities. In recent decades, ports have grown alongside the emerging global 2.1 The increase in international trade has led to a economy and global hubs for large-scale effective trade and corresponding rapid increase in the volume of goods shipping. Traditionally, port authorities were more concerned transported by sea. Despite the enormous growth in maritime about the impact of the environment on their own activities, shipping, most pollution prevention efforts at local, state and rather than vice versa. However, environmental issues have federal levels have focused on other sources of pollution, widened in scope and public awareness has increased, leading while the environmental impacts of ports have increased. The to the establishment of environmental organizations and the result is that the most major ports are heavy pollutants, establishment of rigorous environmental regulations to releasing to a large extent amounts of harmful atmospheric address the problem. The Municipality of Perama is located in and aquatic pollutants that are unmanageable, causing noise the south-western part of the Attica Basin and belongs to the and light pollution that disrupt the surrounding communities Regional Unity of Piraeus and is a city with a great and damage marine habitats. -

Visa & Residence Permit Guide for Students

Ministry of Interior & Administrative Reconstruction Ministry of Foreign Affairs Directorate General for Citizenship & C GEN. DIRECTORATE FOR EUROPEAN AFFAIRS Immigration Policy C4 Directorate Justice, Home Affairs & Directorate for Immigration Policy Schengen Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.ypes.gr www.mfa.gr Visa & Residence Permit guide for students 1 Index 1. EU/EEA Nationals 2. Non EU/EEA Nationals 2.a Mobility of Non EU/EEA Students - Moving between EU countries during my short-term visit – less than three months - Moving between EU countries during my long-term stay – more than three months 2.b Short courses in Greek Universities, not exceeding three months. 2.c Admission for studies in Greek Universities or for participation in exchange programs, under bilateral agreements or in projects funded by the European Union i.e “ERASMUS + (placement)” program for long-term stay (more than three months). - Studies in Greek universities (undergraduate, master and doctoral level - Participation in exchange programs, under interstate agreements, in cooperation projects funded by the European Union including «ERASMUS+ placement program» 3. Refusal of a National Visa (type D)/Rights of the applicant. 4. Right to appeal against the decision of the Consular Authority 5. Annex I - Application form for National Visa (sample) Annex II - Application form for Residence Permit Annex III - Refusal Form Annex IV - Photo specifications for a national visa application Annex V - Aliens and Immigration Departments Contacts 2 1. Students EU/EEA Nationals You will not require a visa for studies to enter Greece if you possess a valid passport from an EU Member State, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway or Switzerland. -

Some Similarities in Mycenaean Palace Plans

SOME SIMILARITIES IN MYCENAEAN PALACE PLANS * J.G. YOUNGER ABSTRACT The plans of the Mycenaean palaces at Pylos and Tiryns reveal major similarities, including the presence of two megara per palace, plus a third, megaron–like structure and a bathroom. These similarities allow for the identification of similar structures at Mycenae (a revised plan is proposed). KEYWORDS Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, palaces, bathrooms. In the three complete Mycenaean palace plans, there more subsidiary rooms on the south–east. In the south– are a few remarkable similarities that may shed some east corner of this central structure is a secondary light on their early histories and reconstructions.1 megaron (the Queen’s Megaron), with its hearth room (46) accessed from the courtyard through Corridors 45/51 and 48 (the latter substituting for the megaron’s I. PYLOS vestibule). It also features two storage rooms (50, 53) I start with the best preserved palace, that at Pylos and a corridor (49) substituting for the megaron’s [Fig. 1].2 The central structure of the palace consists of porch. These two megara make up what Schaar (1979: a megaron (Rooms 4–6: porch, vestibule, and hearth 10–22) calls a ‘double palace’. The South–Western room) flanked by corridors and, off them, subsidiary Building forms, in Schaar’s teminology, an ‘auxiliary’ rooms; it is preceded by a court (3) and gate (1–2), megaron: especially the truncated megaron consisting flanked by the Archives (7, 8) on the north–west and only of two rooms, an access court (64) and a (hearth?) room with four interior columns (65).