1 Chapter 3 a NEW TOYOTAISM? Koïchi Shimizu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

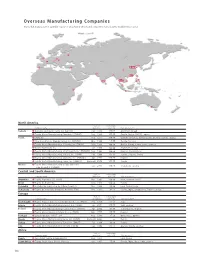

Annual Report 2006

Overseas Manufacturing Companies (Plants that manufacture or assemble Toyota- or Lexus-brand vehicles and component manufacturers established by Toyota) North America Start of Voting rights Company name operations ratio* (%) Main products** Canada 1 Canadian Autoparts Toyota Inc. (CAPTIN) Feb. 1985 100.00 Aluminum wheels 2 Toyota Motor Manufacturing Canada Inc. (TMMC) Nov. 1988 100.00 Corolla, Matrix, RX330, engines U.S.A. 3 TABC, Inc. Nov. 1971 100.00 Catalytic converters, stamping parts, steering columns, engines 4 New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI) Dec. 1984 50.00 Corolla, Tacoma 5 Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Kentucky, Inc. (TMMK) May 1988 100.00 Avalon, Camry, Camry Solara, engines 6 Bodine Aluminum, Inc. Jan. 1993 100.00 Aluminum castings 7 Toyota Motor Manufacturing, West Virginia, Inc. (TMMWV) Nov. 1998 100.00 Engines, transmissions 8 Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Indiana, Inc. (TMMI) Feb. 1999 100.00 Tundra, Sequoia, Sienna 9 Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Alabama, Inc. (TMMAL) Apr. 2003 100.00 Engines 0 Toyota Motor Manufacturing, Texas, Inc. (TMMTX) (planned) 2006 100.00 Tundra Mexico - Toyota Motor Manufacturing de Baja California Sep. 2004 100.00 Truck beds, Tacoma S.de R.L.de.C.V (TMMBC) Central and South America Start of Voting rights Company name operations ratio* (%) Main products** Argentina = Toyota Argentina S.A. (TASA) Mar. 1997 100.00 Hilux, Fortuner (SW4) Brazil q Toyota do Brasil Ltda. May 1959 100.00 Corolla Colombia w Sociedad de Fabricacion de Automotores S.A. Mar. 1992 28.00 Land Cruiser Prado Venezuela e Toyota de Venezuela Compania Anonima (TDV) Nov. 1981 90.00 Corolla, Dyna, Land Cruiser, Terios***, Hilux Europe Start of Voting rights Company name operations ratio* (%) Main products** Czech Republic r Toyota Peugeot Citroën Automobile Czech, s.r.o. -

Sustainability Data Book 2017 Sustainability Data Book 2017

Sustainability Data Book 2017 Sustainability Data Book 2017 Editorial Policy Sustainability Data Book (Former Sustainability Report) focuses on reporting the yearly activities of Toyota such as Toyota CSR management and individual initiatives. Information on CSR initiatives is divided into chapters, including Society, Environment and Governance. We have also made available the “Environmental Report 2017 - Toward Toyota Environmental Challenge 2050” excerpted from the Sustainability Data Book 2017. In the Annual Report, Toyota shares with its stakeholders the ways in which Toyota’s business is contributing to the sustainable development of society and the Earth on a comprehensive basis from a medium- to long-term perspective. Annual Report http://www.toyota-global.com/investors/ir_library/annual/ Securities Reports http://www.toyota.co.jp/jpn/investors/library/negotiable/ Sustainability Data Book 2017 http://www.toyota-global.com/sustainability/report/sr/ SEC Fillings http://www.toyota-global.com/investors/ir_library/sec/ Financial Results Environmental Report 2017 http://www.toyota-global.com/investors/financial_result/ —Toward Toyota Environmental Challenge 2050— http://www.toyota-global.com/sustainability/report/er/ Corporate Governance Reports http://www.toyota-global.com/investors/ir_library/cg/ • The Toyota website also provides information on corporate initiatives not included in the above reports. Sustainability http://www.toyota-global.com/sustainability/ Environment http://www.toyota-global.com/sustainability/environment/ Social Contribution Activities http://www.toyota-global.com/sustainability/social_contribution/ Period Covered Fiscal year 2016 (April 2016 to March 2017) Some of the initiatives in fiscal year 2017 are also included Toyota Motor Corporation (TMC)’s own initiatives and examples of those of its consolidated affiliates, etc., Scope of Report in Japan and overseas. -

Classic Japanese Performance Cars Free

FREE CLASSIC JAPANESE PERFORMANCE CARS PDF Ben Hsu | 144 pages | 15 Oct 2013 | Cartech | 9781934709887 | English | North Branch, United States JDM Sport Classics - Japanese Classics | Classic Japanese Car Importers Not that it ever truly went away. But which one is the greatest? The motorsport-derived all-wheel drive system, dubbed ATTESA Advanced Total Traction Engineering System for All-Terrainuses computers and sensors to work out what the car is doing, and gave the Skyline some particularly special abilities — famously causing some rivalry at the Nurburgring with a few disgruntled Classic Japanese Performance Cars engineers…. The latest R35 GT-R, for the first time a stand-alone model, grew in size, complexity and ultimately speed. A mid-engined sports car from Honda was always going to be special, but the NSX went above and beyond. Honda managed to convince Ayrton Senna, who was at the time driving for McLaren Honda, to assess a late-stage prototype. Honda took what he said onboard, and when the NSX went on sale init was a hugely polished and capable machine. Later cars, especially the uber-desirable Type-R model, were Classic Japanese Performance Cars to perfection. So many Imprezasbut which one to choose? All of the turbocharged Subarusincluding the Legacy and even the bonkers Forrester STi, have got something inherently special to them. Other worthy models include the special edition RB5, as well as the Prodrive fettled P1. All will make you feel like a rally driver…. Mazda took all the best parts of the classic British sports car, and built them into a reliable and equally Classic Japanese Performance Cars package. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 24, 2016 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2016 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Nobukazu Takano Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

Pdf: 660 Kb / 236

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 23, 2017 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2017 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Nobukazu Takano Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

Australia and Japan

DRAFT Australia and Japan A New Economic Partnership in Asia A Report Prepared for Austrade by Peter Drysdale Crawford School of Economics and Government The Australian National University Tel +61 2 61255539 Fax +61 2 61250767 Email: [email protected] This report urges a paradigm shift in thinking about Australia’s economic relationship with Japan. The Japanese market is a market no longer confined to Japan itself. It is a huge international market generated by the activities of Japanese business and investors, especially via production networks in Asia. More than ever, Australian firms need to integrate more closely with these supply chains and networks in Asia. 1 Structure of the Report 1. Summary 3 2. Japan in Asia – Australia’s economic interest 5 3. Assets from the Australia-Japan relationship 9 4. Japan’s footprint in Asia 13 5. Opportunities for key sectors 22 6. Strategies for cooperation 32 Appendices 36 References 42 2 1. Summary Japan is the second largest economy in the world, measured in terms of current dollar purchasing power. It is Australia’s largest export market and, while it is a mature market with a slow rate of growth, the absolute size of the Japanese market is huge. These are common refrains in discussion of the Australia-Japan partnership over the last two decades or so. They make an important point. But they miss the main point about what has happened to Japan’s place in the world and its role in our region and what those changes mean for effective Australian engagement with the Japanese economy. -

A Management Survey of Industry Interaction with Locational Factors

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Japanese Business in Australia: A Management Survey of Industry Interaction with Locational Factors Bayari, Celal Nagoya University Graduate School of International Development 1 January 2004 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/103896/ MPRA Paper No. 103896, posted 02 Nov 2020 16:00 UTC 1 Japanese Business in Australia: A Management Survey of Industry Interaction with Locational Factors Celal Bayari Nagoya University. Graduate School of International Development Citation: Bayari, Celal (2004) ‘Japanese Business in Australia: A Management Survey of Industry Interaction with Locational Factors’. The Otemon Journal of Australian Studies. 30: 119-149. 2004. ISSN 0385-3446. 1 2 JAPANESE BUSINESS IN AUSTRALIA: A MANAGEMENT SURVEY OF INDUSTRY INTERACTION WITH LOCATIONAL FACTORS Celal Bayari Nagoya University. Graduate School of International Development Abstract This is a discussion of research findings on the interaction of the Japanese firms with Australia’s locational factors that affect their investment decisions in Australia. The paper argues that there is a convergence as well as divergence among the sixty-five companies from three industrial sectors on ten different factors affecting satisfaction that is reported by the management and the other variables that characterise the firms.1 Japan-Australia relations: Introduction Japan has always captured the imagination of Australian business leaders and politicians (Stockwin 1972, Meaney 1988) and economic planners (Japan Secretariat 1984) in the post-war era. In the Japanese media the image of Australia is one of a tourist location and raw materials supplier that buys cars and electronics goods from Japan (The Japan Times 2001: 15). Australian exports to Japan add up to 380,000 jobs, AUS $1,300 for every Australian, and 4% of the GDP (Vaile 2001). -

Analysis on the Influential Factors of Japanese Economy

E3S Web of Conferences 233, 01156 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123301156 IAECST 2020 Analysis on the Influential Factors of Japanese Economy Tongye Wang1,a 1School of Economics, the University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, 2000, Australia ABSTRACT-Japan is known as a highly developed capitalist country. It was the third largest economy in the world by the end of 2017 and is one of the members of G7 and G20. Thus, for academic purpose, it is worth to discuss how Japan could expand the scale of its economy in different kinds of effective ways in the past half a century. This paper will talk about the main factors to influence the Japanese economy from post-war period to twenty- first century. The Solow-Swan model is used to target on explaining the factors that influence the long-run economic development in an economy. To present the effects that was brought by the past policies, both total GDP calculation and GDP per capita calculation are adopted as the evidence of economic success of Japan. industries further, and finally had achieved a huge success which brought Japan out of the previous stagnant situation. 1 INTRODUCTION For this post-war economic miracle, relevant studies had After 1945, the world economy tends to be integrated due figured out that the core of success is consisted with two to the demands of post-war reconciliation. In this situation, principal proposes: first, the successful economic reform the competitions and cooperation among countries on adopting Inclined Production Mode. The Inclined become more intensive as time goes by. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 25, 2012 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended: March 31, 2012 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number: 001-14948 TOYOTA JIDOSHA KABUSHIKI KAISHA (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION (Translation of Registrant’s Name into English) Japan (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City Aichi Prefecture 471-8571 Japan +81 565 28-2121 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) Kenichiro Makino Telephone number: +81 565 28-2121 Facsimile number: +81 565 23-5800 Address: 1 Toyota-cho, Toyota City, Aichi Prefecture 471-8571, Japan (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of registrant’s contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class: Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered: American Depositary Shares* The New York Stock Exchange Common Stock** * American Depositary Receipts evidence American Depositary Shares, each American Depositary Share representing two shares of the registrant’s Common Stock. ** No par value. Not for trading, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the U.S. -

Case Studies in Change from the Japanese Automotive Industry

UC Berkeley Working Paper Series Title Keiretsu, Governance, and Learning: Case Studies in Change from the Japanese Automotive Industry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/43q5m4r3 Authors Ahmadjian, Christina L. Lincoln, James R. Publication Date 2000-05-19 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Institute of Industrial Relations University of California, Berkeley Working Paper No. 76 May 19, 2000 Keiretsu, governance, and learning: Case studies in change from the Japanese automotive industry Christina L. Ahmadjian Graduate School of Business Columbia University New York, NY 10027 (212)854-4417 fax: (212)316-9355 [email protected] James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California at Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 643-7063 [email protected] We are grateful to Nick Argyres, Bob Cole, Ray Horton, Rita McGrath, Atul Nerkar, Toshi Nishiguchi, Joanne Oxley, Hugh Patrick, Eleanor Westney, and Oliver Williamson for helpful comments. We also acknowledge useful feedback from members of the Sloan Corporate Governance Project at Columbia Law School. Research grants from the Japan – U. S. Friendship Commission, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and the Clausen Center for International Business and Policy of the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley are also gratefully acknowledged. Keiretsu, governance, and learning: Case studies in change from the Japanese automotive industry ABSTRACT The “keiretsu” structuring of assembler-supplier relations historically enabled Japanese auto assemblers to remain lean and flexible while enjoying a level of control over supply akin to that of vertical integration. Yet there is much talk currently of breakdown in keiretsu networks. -

Toyota in the World 2011

"Toyota in the World 2011" is intended to provide an overview of Toyota, including a look at its latest activities relating to R&D (Research & Development), manufacturing, sales and exports from January to December 2010. It is hoped that this handbook will be useful to those seeking to gain a better understanding of Toyota's corporate activities. Research & Development Production, Sales and Exports Domestic and Overseas R&D Sites Overseas Production Companies North America/ Latin America: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Technological Development Europe/Africa: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Asia: Market/Toyota Sales and Production History of Technological Development (from 1990) Oceania & Middle East: Market/Toyota Sales and Production Operations in Japan Vehicle Production, Sales and Exports by Region Overseas Model Lineup by Country & Region Toyota Group & Supplier Organizations Japanese Production and Dealer Sites Chronology Number of Vehicles Produced in Japan by Model Product Lineup U.S.A. JAPAN Toyota Motor Engineering and Manufacturing North Head Office Toyota Technical Center America, Inc. Establishment 1954 Establishment 1977 Activities: Product planning, design, Locations: Michigan, prototype development, vehicle California, evaluation Arizona, Washington D.C. Activities: Product planning, Vehicle Engineering & Evaluation Basic Research Shibetsu Proving Ground Establishment 1984 Activities: Vehicle testing and evaluation at high speed and under cold Calty Design Research, Inc. conditions Establishment 1973 Locations: California, Michigan Activities: Exterior, Interior and Color Design Higashi-Fuji Technical Center Establishment 1966 Activities: New technology research for vehicles and engines Toyota Central Research & Development Laboratories, Inc. Establishment 1960 Activities: Fundamental research for the Toyota Group Europe Asia Pacific Toyota Motor Europe NV/SA Toyota Motor Asia Pacific Engineering and Manfacturing Co., Ltd. -

COMPACT TRUCK/TACOMA, 4X2

**NOTE: All chronology dates are model year, unless noted otherwise. CY refers to “Calendar Year.”** COMPACT TRUCK/TACOMA, 4x2 Series Chronology 1964 - Stout introduced to U.S. 1969 - Hi-Lux compact truck introduced with 1.9L engine. 1970 - Hi-Lux receives new engine. 1972 - Third generation engine debuts in Hi-Lux. 1973 - CY 1972 1/2 - 2nd generation Hi-Lux. 1973 - Available with extended cargo-bed. 1974 - CY 1974 - Wins "Pickup Truck of the Year" from Pickup, Van & 4WD. 1975 - Third generation, larger engine. 1975 - 5-spd manual transmission available. 1976 - Pickup name replaces Hi-Lux on U.S.-market trucks. 1977 (September) - 1-millionth truck produced. 1977 - SR5 grade introduced. 1979 - Fourth generation. 1981 - Receives larger gasoline engine and available diesel engine. SR5 wins "Four Wheeler of the Year", Four Wheeler Magazine. 1983 - Last year of 4-speed manual transmission. 1984 - 5th generation. 1984 - Xtracab, turbocharged gasoline and diesel engines available. SR5 wins "Four Wheeler of the Year", Four Wheeler Magazine. 1986 - Last year of diesel engine availability. 1989 - Sixth generation, introduction of V-6. 1989 - CY 1989 - Wins "Truck of the Year", Motor Trend 1989 - CY 1989 - SR5 wins "Pickup Truck of the Year", Four Wheeler Magazine. 1995 - Sixth generation, introduced as 1995 1/2 model. 1995 - Introduction of Tacoma name. 1995 - "Import Truck of the Year" - Automundo magazine. 1996 - "Best Compact Pickup in Initial Quality" - J.D. Power & Associates. Tacoma Xtra Cab wins "Pickup Truck of the Year", Four Wheeler Magazine. 1997 - Minor revision to front styling. 1997 - "Best Vehicle in Initial Quality-Compact Pickup segment" - J.D.