Does Avoiding Judicial Isolation Outweigh the Risks Related to “Professional Death by Facebook”?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

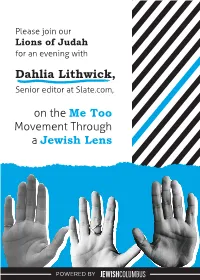

Dahlia Lithwick Invite Draft5

Please join our Lions of Judah for an evening with Dahlia Lithwick, Senior editor at Slate.com, on the Me Too Movement Through a Jewish Lens POWERED BY Dahlia Lithwick is a senior editor at Slate, and in that capacity, has been writing their “Supreme Court Dispatches” and “Jurisprudence” columns since 1999. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and Commentary, among other places. She is host of Amicus, Slate’s award-winning biweekly podcast about the law and the Supreme Court. She was Newsweek’s legal columnist from 2008 until 2011. Ms. Lithwick speaks frequently on the subjects of criminal justice reform, reproductive freedom, and religion in the courts. She has appeared on CNN, ABC, The Colbert Report, the Daily Show and is a frequent guest on The Rachel Maddow Show. She has testified before Congress about access to justice in the era of the Roberts Court. Ms. Lithwick earned her BA in English from Yale University and her JD degree from Stanford University. JewishColumbus’s Lion of Judah Society (LOJ) was established to provide women an opportunity to engage with their peers and increase their impact with a collective voice. Lions are women who make leadership gifts, as individuals or as part of a family gift, of $5,000 or more through JewishColumbus’s Annual Campaign. Lion of Judah dinner featuring Dahlia Lithwick, Thursday, June 4 The Terrace 711 North High Street, Columbus, OH 43215 Free valet parking Tickets: $50 each Link TBD Please RSVP by May 18 Dietary restrictions observed, catering provided by Cameron Mitchell Women’s Philanthropy Co-Chairs Jane Bodner & Emily Kandel Lion of Judah Co-Chairs Gigi Fried & Shelly Igdaloff Lion Event Co-Chairs Margie Goldach & Clemy Keidan Questions? Please contact Rachel Gleitman, Director of Women’s Philanthropy at [email protected] This event is open to Lions of Judah and Step Up Lions. -

NYU Law Review

40216-nyu_93-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/02/2018 12:38:48 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\93-2\NYU201.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-MAY-18 8:21 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 93 MAY 2018 NUMBER 2 ARTICLES CONSTITUTIONAL LAW IN AN AGE OF ALTERNATIVE FACTS ALLISON ORR LARSEN* Objective facts—while perhaps always elusive—are now an endangered species. A mix of digital speed, social media, fractured news, and party polarization has led to what some call a “post-truth” society: a culture where what is true matters less than what we want to be true. At the same moment in time when “alternative facts” reign supreme, we have also anchored our constitutional law in general observations about the way the world works. Do violent video games harm child brain develop- ment? Is voter fraud widespread? Is a “partial-birth abortion” ever medically nec- essary? Judicial pronouncements on questions like these are common, and— perhaps more importantly—they are being briefed by sophisticated litigants who know how to grow the factual dimensions of their case in order to achieve the constitutional change that they want. The combination of these two forces—fact-heavy constitutional law in an environ- 40216-nyu_93-2 Sheet No. 3 Side A 05/02/2018 12:38:48 ment where facts are easy to manipulate—is cause for serious concern. This Article explores what is new and worrisome about fact-finding today, and it identifies con- stitutional disputes loaded with convenient but false claims. To remedy the problem, we must empower courts to proactively guard against alternative facts. -

Justice Scalia and Fourth Estate Skepticism Ronnell Anderson Jones S.J

SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah Utah Law Digital Commons Utah Law Faculty Scholarship Utah Law Scholarship 2017 Justice Scalia and Fourth Estate Skepticism RonNell Anderson Jones S.J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship Part of the First Amendment Commons, Judges Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation 15 First Amend. L. Rev. 258, 287 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Utah Law Scholarship at Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE SCALIA AND FOURTH ESTATE SKEPTICISM RonNell Andersen Jones* INTRODUCTION When news broke of the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, some aspects of the Justice's legacy were instantly apparent. It was immediately clear that he would be remembered for his advocacy of constitutional originalism, his ardent opposition to the use of legislative history in statutory interpretation, and his authorship of the watershed Second Amendment case of the modern era.1 Yet there are other, less obvious but equally significant ways that Justice Scalia made his own unique mark and left behind a Court that was fundamentally different than the one he had joined thirty years earlier. Among them is the way he impacted the relationship between the Court and the press. When Scalia was confirmed as a Justice of the U.S. -

Dahlia Lithwick: American Jews' Love Affair with the Law

DAHLIA LITHWICK: AMERICAN JEWS' LOVE AFFAIR WITH THE LAW (Begin audio) Joshua Holo: Welcome to the college comments podcast, passionate perspectives, from Judaism's leading thinkers, brought to you by the Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion, America's first Jewish institution of higher learning. My name is Joshua Holo of HUC's Jack-H Skirball campus in Los Angeles, and your host. You're listening to a special episode recorded at Symposium 2, a conference held in Los Angeles at Stephen Wise Temple in November of 2018. JH: It's my great pleasure to welcome Dahlia Lithwick to the college comments podcast. Dahlia Lithwick is a senior editor at Slate, and has been writing their Supreme Court dispatches and jurisprudence columns since 1999. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper's, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New Republic and Commentary. And she is the host of Amicus, Slate's award-winning bi-weekly podcast about the law and the Supreme Court. And I know that many of our listeners will have heard Dahlia Lithwick in some capacity or another, so it is really an honor and a pleasure to have you. Thank you for joining us. Dahlia Lithwick: It's an honor and a pleasure to be here, thank you. JH: So we're gonna start with the Jewish name game, you and I share something which is last names that no one would think are Jewish if they didn't know us. My family is Turkish, and changed its name, which in the Turkish-Jewish world is known as a Jewish name, but it was Americanized from Halio to Holo. -

Trump, Twitter, and the Russians: the Growing Obsolescence of Federal Campaign Finance Law

3. FINAL GAUGHAN (DO NOT DELETE) 2/27/2018 5:43 PM TRUMP, TWITTER, AND THE RUSSIANS: THE GROWING OBSOLESCENCE OF FEDERAL CAMPAIGN FINANCE LAW ANTHONY J. GAUGHAN* I. INTRODUCTION The 2016 presidential campaign defied the conventional wisdom in virtually every regard. Donald Trump’s surprise victory disproved the polls and embarrassed the pundits in the biggest election upset since the 1948 Truman-Dewey race.1 But the 2016 election was more than a political earthquake. The campaign also made it starkly apparent that federal campaign finance law has become woefully outdated in the age of the internet, social media, and non-stop fundraising. A vestige of the post- Watergate reforms of the 1970s, the Federal Election Campaign Act (“FECA”) no longer adequately regulates the campaign finance world of twenty-first century American politics. The time has come for a sweeping reform and restructuring of the law. Since FECA’s adoption in the 1970s, federal campaign finance law has been built on four pillars. The first is contribution limits on donations to candidate campaigns and political party committees. Contribution limits are designed to reduce the role of money in politics by preventing large donors from corrupting elected officials. The second is the ban on foreign contributions to American political campaigns. The prohibition is intended to prevent foreign influence on American elections and to ensure that * Professor of Law, Drake University Law School; J.D. Harvard University, 2005; Ph.D. (history) University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2002; M.A. Louisiana State University, 1996; B.A. University of Minnesota, 1993. The author would like to thank Paul Litton and the University of Missouri Law School faculty for very helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article that the author presented at Mizzou Law. -

Human Experience and Supreme Court Decision Making on Criminal Justice Christopher E

Marquette Law Review Volume 99 Article 9 Issue 3 Spring 2016 What If?: Human Experience and Supreme Court Decision Making on Criminal Justice Christopher E. Smith Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Repository Citation Christopher E. Smith, What If?: Human Experience and Supreme Court Decision Making on Criminal Justice, 99 Marq. L. Rev. 813 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol99/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT IF?: HUMAN EXPERIENCE AND SUPREME COURT DECISION MAKING ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE CHRISTOPHER E. SMITH* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 813 II. HUMAN EXPERIENCE AND JUDICIAL DECISIONS ........................ 818 A. The Liberalizing Impact of Life Experiences: John Paul Stevens ........................................................................................ 819 B. Intriguing Questions About the Impact of Life Experiences: Justice Antonin Scalia ............................................................... 822 C. Impervious to Life Experience Influence?: Justice Clarence Thomas ...................................................................................... -

Dahlia Lithwick

Dahlia Lithwick Dahlia Lithwick is a senior editor at Slate, and in that capacity, has been writing their "Supreme Court Dispatches" and "Jurisprudence" columns since 1999. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and Commentary, among other places. She is host of Amicus, Slate’s award-winning biweekly podcast about the law and the Supreme Court. She was Newsweek’s legal columnist from 2008 until 2011. In 2018 Lithwick received the American Constitution Society’s Progressive Champion Award, the Hillman Prize for Opinion and Analysis, and was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 2017, Lithwick was the recipient of a Golden Pen Award from the Legal Writing Institute; the Virginia Bar Association’s award for Excellence in Legal Journalism; and the 2017 award for Outstanding Journalist in Law from the Burton Foundation for a distinguished career in journalism in law. Lithwick won a 2013 National Magazine Award for her columns on the Affordable Care Act. She has been twice awarded an Online Journalism Award for her legal commentary. Lithwick has held visiting faculty positions at the University of Georgia Law School, the University of Virginia School of Law, and the Hebrew University Law School in Jerusalem. Ms. Lithwick has delivered the annual Constitution Day Lecture at the United States Library of Congress in 2012 and 2011. She has been a featured speaker on the main stage at the Chautauqua Institution. She speaks frequently on the subjects of criminal justice reform, reproductive freedom, religion in the courts. -

The Ginsburg Court? a Contrarian View

THE GINSBURG COURT? A CONTRARIAN VIEW Benjamin Beaton* JUNE 2010: SCENE CHANGE During the last week of June 2010, the life of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the history of the U.S. Supreme Court changed forever: • June 27: Justice Ginsburg’s “biggest booster”1 and larger-than-life2 husband, Marty, lost a long bout with cancer. • June 28: Ginsburg returned to the bench to announce an opinion during the final day of the Court’s term.3 • Hours later: Justice John Paul Stevens retired, informally elevating Ginsburg to the seniormost position on the more liberal side of the Court.4 As if that weren’t enough, just two days later the diminutive New York progressive—clearly still grieving—interviewed and soon hired a lanky conservative law clerk from Kentucky. Unlike the rest of the week’s events, this hiring of an aberrant “counterclerk”—now a baby judge back in the Bluegrass State—would not, far as I know, leave any discernible imprint on history. Though perhaps it should’ve tipped us off: The Court in the 2010s might look a little different than what came before. On one level, it surely did. The Court, try as it might, rarely escaped the headlines during the ten years between Justice Stevens’s departure in 2010 and Justice Ginsburg’s in 2020. On another level, however, the Court * Judge, U.S. District Court for the Western District of Kentucky, and law clerk to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg during October Term 2011. 1. Michael S. Rosenwald, “My Dearest Ruth”: The Remarkable Devotion of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Husband, Wash. -

Why Justice Thomas Should Speak at Oral Argument

:+<-867,&(7+20$66+28/'63($.$725$/ $5*80(17 ∗ 'DYLG$.DUS , ,1752'8&7,21 ,, 7+(9$/8(2)25$/$5*80(17 ,,, 7+(6281'2)6,/(1&( ,9 7+(())(&72)6,/(1&( 9 ³0<&2//($*8(66+28/'6+8783´ $ 'HFRUXP % /LVWHQLQJ & .HHSLQJDQ2SHQ0LQG ' %URDGHQLQJWKH'HEDWH ( 'LPLQLVKLQJ+LV6WDWXUH 9, 7+(32:(52):25'6 9,, &21&/86,21 ,,1752'8&7,21 7KHRUDODUJXPHQWEHIRUHWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV6XSUHPH&RXUWLQ0RUVHY )UHGHULFNEHJDQDWDPLQW\SLFDOIDVKLRQOLNHDKLJKVSHHGJDPH RIFKHVV)RUW\WZRVHFRQGVLQWRWKHDUJXPHQW-XVWLFH$QWKRQ\.HQQHG\ FXWRIIWKHDGYRFDWHLQPLGVHQWHQFH)RUWKHQH[WKRXUDQGWHQPLQXWHV WKH-XVWLFHVLQWHUUXSWHGWKHODZ\HUVWLPHV-XVWLFH6WHSKHQ%UH\HUD IRUPHUODZSURIHVVRUSRVHGDPXOWLSDUWK\SRWKHWLFDO-XVWLFH5XWK%DGHU ∗ -'8QLYHUVLW\RI)ORULGD/HYLQ&ROOHJHRI/DZ%$<DOH8QLYHUVLW\)RU 0DULVDZKRMRLQHGPHRQWKLVDGYHQWXUH$OVRWKDQNVWR3URIHVVRUV6KDURQ5XVKDQG0LFKDHO 6HLJHODQGWR$QQ+RYH&DUROLQH0F&UDHDQG%HQ³=LJJ\´:LOOLDPVRQIRUWKHLUFORVHUHDGLQJRI WKLV1RWH 6&W 6HH7UDQVFULSWRI2UDO$UJXPHQWDW0RUVH6&W 1R .(9,10(5,'$ 0,&+$(/$)/(7&+(56835(0(',6&20)2577+(',9,'('628/2) &/$5(1&(7+20$6 +HDU5HFRUGLQJRI2UDO$UJXPHQWRQ0DU0RUVH6&W 1R DYDLODEOHDWKWWSZZZR\H]RUJFDVHVBBDUJXPHQW ,G ,GVHH0LFKDHO'R\OH:LUH6HUYLFH5HSRUW7UDQVFULSWV*LYHD*OLPSVHLQWR0DQ\ -XVWLFHV¶ 3HUVRQDOLWLHV 0&&/$7&+< 1(:63$3(56 0D\ DYDLODEOH DW :/15 GHVFULELQJ -XVWLFH %UH\HU DV ³SDLQIXOO\ SURIHVVRULDO´ DQG ³WKH PRVW YHUERVH RI WKH 612 FLORIDA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61 Ginsburg, a civil procedure scholar, asked about a key detail in the record;7 Justice Antonin Scalia’s rejoinders drew laughs from the audience.8 The Court wrestled during the argument with the reach of a student’s First Amendment right to unfurl a banner at a school-sponsored, off- campus event.9 Yet, during the hour-long exchange, no Justice questioned the basic premise that students retain some First Amendment rights at school.10 However, when the Court issued its opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas in a concurrence announced an extraordinary position: that the First Amendment does not apply at all to students.11 He wrote that the Court should overrule the leading precedent, Tinker v. -

A Humble Justice Marah Stith Mcleod

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL FORUM A UGUST 2, 2017 A Humble Justice Marah Stith McLeod Justice Thomas’s criminal law opinions have provoked acerbic commentary in the press and academic writing.1 Not even a year into his tenure on the Su- preme Court, an editorial in the New York Times labeled him the “youngest, cruelest Justice.”2 A later media account branded criminal case opinions by Jus- tice Thomas among the “meanest Supreme Court decisions ever,” though for Justice Thomas, the writer made clear, these opinions were “cruel but not unu- s u a l .” 3 The article accused Justice Thomas of “stak[ing] out positions that revel in the hyper-technical and deliberately callous.”4 This unstudied denunciation of Justice Thomas’s opinions imposes a high and unnecessary cost on law students and others who might otherwise profit from being exposed to Justice Thomas’s brand of originalism as part of the broad spectrum of good-faith approaches judges may take to the law. 1. See, e.g., Eric L. Muller, Where But for the Grace of God Goes He? The Search for Empathy in the Criminal Jurisprudence of Clarence Thomas, 15 CONST. COMMENT. 225 (1998). 2. Opinion, The Youngest, Cruelest Justice, N.Y. TIMES (Feb. 27, 1992), http:// www.nytimes.com/1992/02/27/opinion/the-youngest-cruelest-justice.html [http://perma .cc/KK24-8K2T] (condemning Justice Thomas’s dissent in Hudson v. McMillian, 503 U.S. 1, 17 (1992)). 3. Dahlia Lithwick, Cruel But Not Unusual, SLATE (Apr. 1, 2011, 7:43 PM), http://www.slate .com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2011/04/cruel_but_not_unusual.html [http://perma.cc/AF8G-9ZMR] (criticizing Justice Thomas’s majority opinion in Connick v. -

A Humble Justice Marah S

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2017 A Humble Justice Marah S. McLeod [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Marah S. McLeod, A Humble Justice, 127 Yale L.J. F. 196 (2017). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/1309 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE YALE LAW JOURNAL FORUM AUGUST 2, 2017 A Humble Justice Marah Stith McLeod Justice Thomas's criminal law opinions have provoked acerbic commentary in the press and academic writing. Not even a year into his tenure on the Su- preme Court, an editorial in the New York Times labeled him the "youngest, cruelest Justice."2 A later media account branded criminal case opinions by Jus- tice Thomas among the "meanest Supreme Court decisions ever," though for Justice Thomas, the writer made clear, these opinions were "cruel but not unu- sual'" The article accused Justice Thomas of "stak[ing] out positions that revel in the hyper-technical and deliberately callous."' This unstudied denunciation of Justice Thomas's opinions imposes a high and unnecessary cost on law students and others who might otherwise profit from being exposed to Justice Thomas's brand of originalism as part of the broad spectrum of good-faith approaches judges may take to the law. -

Written Materials and Resources July 8, 2021 Supreme Court Review Table of Contents

ADL’s Annual Supreme Court Review Written Materials and Resources July 8, 2021 Supreme Court Review Table of Contents 22nd Annual Supreme Court Review Agenda………………………2 22nd Annual Supreme Court Review Speaker Biographies…….. 3 Overview of Supreme Court Review 2021 Cases……………….... 8 In the Courts: ADL’s Legal Docket 2019-21……………………….. 14 22nd Annual Supreme Court Review A Joint Virtual Presentation by ADL and the National Constitution Center July 8, 2021 12:00pm – 1:30pm EDT Agenda 1. National Constitution Center Introduction 2. ADL Welcome 3. Supreme Court – 2020 Term Term Overview COVID-19 cases • Tandon v. Newsom • Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, New York v. Cuomo • South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom • Harvest Rock Church v. Newsom • Gish v. Newsom LGBTQ+ Rights • Fulton v. Philadelphia • Gloucester County School Board v. Grimm Free Speech • Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. Voting Rights • Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee Immigration • Sanchez v. Mayorkas Affordable Care Act • California v. Texas Corporate Accountability • Nestlé USA, Inc. v. Doe Juvenile Life Without Parole • Jones v. Mississippi Union Rights • Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid Native American Rights • United States v. Cooley 4. Looking Ahead 5. Q&A ©2021 ADL 2 nd 22 ANNUAL SUPREME COURT REVIEW Speaker Biographies Dahlia Lithwick Dahlia Lithwick is a Senior Editor at Slate.com, where she has been covering the Supreme Court and Jurisprudence since 1999. She was Newsweek’s legal columnist from 2008 until 2011. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Harper’s, The Atlantic, New York Magazine, The Washington Post, Elle, Glamour, and Commentary, among other places.