The Ginsburg Court? a Contrarian View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Avoidance and the Roberts Court Neal Devins William & Mary Law School, [email protected]

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2007 Constitutional Avoidance and the Roberts Court Neal Devins William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Devins, Neal, "Constitutional Avoidance and the Roberts Court" (2007). Faculty Publications. 346. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/346 Copyright c 2007 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs CONSTITUTIONAL A VOIDANCE AND THE ROBERTS COURT Neal Devins • This essay will extend Phil Frickey's argument about the Warren Court's constitutional avoidance to the Roberts Court. My concern is whether the conditions which supported constitutional avoidance by the Warren Court support constitutional avoidance by today's Court. For reasons I will soon detail, the Roberts Court faces a far different Congress than the Warren Court and, as such, need not make extensive use of constitutional avoidance. In Getting from Joe to Gene (McCarthy), Phil Frickey argues that the Warren Court avoided serious conflict with Congress in the late 1950s by exercising subconstitutional avoidance. 1 In other words, the Court sought to avoid congressional backlash by refraining from declaring statutes unconstitutional. Instead, the Court sought to invalidate statutes or congressional actions based on technicalities. If Congress disagreed with the results reached by the Court, lawmakers could have taken legislative action to remedy the problem. This practice allowed the Court to maintain an opening through which it could backtrack and decide similar cases differently without reversing a constitutional decision. In understanding the relevance of Frickey's argument to today's Court, it is useful to compare Court-Congress relations during the Warren Court of the late 1950s to those during the final years of the Rehnquist Court. -

Video Games in the Supreme Court

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2017 Newbs Lose, Experts Win: Video Games in the Supreme Court Angela J. Campbell Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1988 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3009812 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Angela J. Campbell* Newbs Lose, Experts Win: Video Games in the Supreme Court Table of Contents I. Introduction .......................................... 966 II. The Advantage of a Supreme Court Expert ............ 971 A. California’s Counsel ............................... 972 B. Entertainment Merchant Association’s (EMA) Counsel ........................................... 973 III. Background on the Video Game Cases ................. 975 A. Cases Prior to Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n .............................................. 975 B. Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Ass’n .......... 978 1. Before the District Court ...................... 980 2. Before the Ninth Circuit ....................... 980 3. Supreme Court ................................ 984 IV. Comparison of Expert and Non-Expert Representation in Brown ............................................. 985 A. Merits Briefs ...................................... 985 1. Statement of Facts ............................ 986 a. California’s Statement -

The Roles of Sonia Sotomayor in Criminal Justice Cases * Christopher E

THE ROLES OF SONIA SOTOMAYOR IN CRIMINAL JUSTICE CASES * CHRISTOPHER E. SMITH AND KSENIA PETLAKH I. INTRODUCTION The unexpected death of Justice Antonin Scalia in February 20161 reminded Americans about the uncertain consequences of changes in the composition of the Supreme Court of the United States.2 It also serves as a reminder that this is an appropriate moment to assess aspects of the last major period of change for the Supreme Court when President Obama appointed, in quick succession, Justices Sonia Sotomayor in 20093 and Elena Kagan in 2010.4 Although it can be difficult to assess new justices’ decision-making trends soon after their arrival at the high court,5 they may begin to define themselves and their impact after only a few years.6 Copyright © 2017, Christopher Smith and Ksenia Petlakh. * Christopher E. Smith is a Professor of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University. A.B., Harvard University, 1980; M.Sc., University of Bristol (U.K.); J.D., University of Tennessee, 1984; Ph.D., University of Connecticut, 1988. Ksenia Petlakh is a Doctoral student in Criminal Justice, Michigan State University. B.A., University of Michigan- Dearborn, 2012. 1 Adam Liptak, Antonin Scalia, Justice on the Supreme Court, Dies at 79, N.Y. TIMES (Feb. 13, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/us/antonin-scalia-death.html [https:// perma.cc/77BQ-TFEQ]. 2 Adam Liptak, Supreme Court Appointment Could Reshape American Life, N.Y. TIMES (Feb. 18, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/19/us/politics/scalias-death-offers-best- chance-in-a-generation-to-reshape-supreme-court.html [http://perma.cc/F9QB-4UC5]; see also Edward Felsenthal, How the Court Can Reset After Scalia, TIME (Feb. -

Public Opinion As a Meager Influence in Shaping Contemporary Supreme Court Decision Making

Michigan Law Review Volume 109 Issue 6 2011 But How Will the People Know? Public Opinion as a Meager Influence in Shaping Contemporary Supreme Court Decision Making Tom Goldstein SCOTUSblog Amy Howe SCOTUSblog Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Tom Goldstein & Amy Howe, But How Will the People Know? Public Opinion as a Meager Influence in Shaping Contemporary Supreme Court Decision Making, 109 MICH. L. REV. 963 (2011). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol109/iss6/7 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUT HOW WILL THE PEOPLE KNOW? PUBLIC OPINION AS A MEAGER INFLUENCE IN SHAPING CONTEMPORARY SUPREME COURT DECISION MAKING Tom Goldstein* Amy Howe** THE WILL OF THE PEOPLE: How PUBLIC OPINION HAS INFLUENCED THE SUPREME COURT AND SHAPED THE MEANING OF THE CONSTITUTION. By Barry Friedman.New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2009. Pp. 614. $35. INTRODUCTION Chief Justice John Roberts famously described the ideal Supreme Court Justice as analogous to a baseball umpire, who simply "applies" the rules, rather than -

Lydia Polgreen Editor-In-Chief, Huffpost Media Masters – April 4, 2019 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Lydia Polgreen Editor-in-Chief, HuffPost Media Masters – April 4, 2019 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with people at the top at the media game. Today I’m here in New York and joined by Lydia Polgreen, editor-in-chief of HuffPost. Appointed in 2016, she previously spent 15 years at the New York Times where she served as foreign correspondent in Africa and Asia. She received numerous awards for her work, including a George Polk award for her coverage of ethnic violence in Darfur in 2006. Lydia carried out a number of roles at the Times, most recently as editorial director of NYT global. She’s also a board member at Columbia Journalism Review, and the Committee to Protect Journalists. Lydia, thank you for joining me. It’s a pleasure to be here. So Lydia, editor-in-chief of HuffPost, obviously an iconic brand with an amazing history. Where are you going to take it next? Well, I think past is prologue and the future is unknown. Oh, that’s good. I like that already. We’re starting off on the deeply profound. Continue! Well, I think for media right now, it’s a really fascinating moment of both rediscovery of our roots – and those roots really lie in what’s at the core of journalism, which is exposing things that weren’t meant to be known, or that people, important people especially, don’t want to be known, and bringing them to light. -

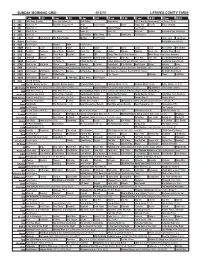

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

John C. Andrews

Verizon Media EMEA Limited 5-7 Point Square, North Wall Quay Dublin 1, Ireland Tel.: +353 1 866 3100 Fax: +353 1 866 3101 Reg: 426324 Commissioner Didier Reynders EUROPEAN COMMISSION JUSTICE Rue de la Loi, 200 1049 Brussels BELGIUM 2 April 2020 Dear Commissioner Reynders, I refer to the letter dated 24 March addressed to our CEO Mr. Guru Gowrappan. Verizon Media, the parent company of Yahoo, HuffPost, AOL and TechCrunch, is focused on making a positive impact on society during this challenging time. We are committed to providing our users with information they can trust and keeping our platforms safe from malicious actors who may seek to take advantage of the COVID-19 crisis. We have carefully monitored the COVID-19 public health emergency and are scrutinizing all ads with an increased focus on sensitivity to public health guidance and risks. Our Ad Policies prohibit ads that claim that any medicine, surgical treatment, or device can prevent or cure coronavirus. Our automated systems flag high-risk ads for manual review and those that violate policy, including COVID-19-related ads, are blocked. We recognize that our 900 million users across the globe rely on us to deliver accurate, reliable news and information. To this end, we have created a coronavirus hub, covid19.yahoo.com, across the Yahoo ecosystem (News, Finance, Sports, Lifestyle & Entertainment), that includes news in real-time about the pandemic across the globe. There is specific content for specific markets, including France (fr.yahoo.com/topics/liste-coronavirus-france), Italy (it.yahoo.com/topics/coronavirus), Germany (de.yahoo.com/topics/Coronavirus), Spain (es.yahoo.com/topics/coronavirus) and the UK (uk.yahoo.com/topics/coronavirus-news). -

Clerk and Justice: the Ties That Bind John Paul Stevens and Wiley B

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Connecticut Law Review School of Law 2008 Clerk and Justice: The Ties That Bind John Paul Stevens and Wiley B. Rutledge Laura Krugman Ray Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review Recommended Citation Ray, Laura Krugman, "Clerk and Justice: The Ties That Bind John Paul Stevens and Wiley B. Rutledge" (2008). Connecticut Law Review. 5. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/law_review/5 CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 41 NOVEMBER 2008 NUMBER 1 Article Clerk and Justice: The Ties That Bind John Paul Stevens and Wiley B. Rutledge LAURA KRUGMAN RAY Justice John Paul Stevens, now starting his thirty-third full term on the Supreme Court, served as law clerk to Justice Wiley B. Rutledge during the Court’s 1947 Term. That experience has informed both elements of Stevens’s jurisprudence and aspects of his approach to his institutional role. Like Rutledge, Stevens has written powerful opinions on issues of individual rights, the Establishment Clause, and the reach of executive power in wartime. Stevens has also, like Rutledge, been a frequent author of dissents and concurrences, choosing to express his divergences from the majority rather than to vote in silence. Within his chambers, Stevens has in many ways adopted his own clerkship experience in preference to current models. Unlike the practices of most of his colleagues, Stevens hires fewer clerks, writes his own first drafts, and shares certiorari decisionmaking with his clerks. -

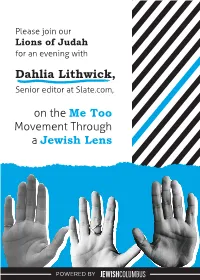

Dahlia Lithwick Invite Draft5

Please join our Lions of Judah for an evening with Dahlia Lithwick, Senior editor at Slate.com, on the Me Too Movement Through a Jewish Lens POWERED BY Dahlia Lithwick is a senior editor at Slate, and in that capacity, has been writing their “Supreme Court Dispatches” and “Jurisprudence” columns since 1999. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Harper’s, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and Commentary, among other places. She is host of Amicus, Slate’s award-winning biweekly podcast about the law and the Supreme Court. She was Newsweek’s legal columnist from 2008 until 2011. Ms. Lithwick speaks frequently on the subjects of criminal justice reform, reproductive freedom, and religion in the courts. She has appeared on CNN, ABC, The Colbert Report, the Daily Show and is a frequent guest on The Rachel Maddow Show. She has testified before Congress about access to justice in the era of the Roberts Court. Ms. Lithwick earned her BA in English from Yale University and her JD degree from Stanford University. JewishColumbus’s Lion of Judah Society (LOJ) was established to provide women an opportunity to engage with their peers and increase their impact with a collective voice. Lions are women who make leadership gifts, as individuals or as part of a family gift, of $5,000 or more through JewishColumbus’s Annual Campaign. Lion of Judah dinner featuring Dahlia Lithwick, Thursday, June 4 The Terrace 711 North High Street, Columbus, OH 43215 Free valet parking Tickets: $50 each Link TBD Please RSVP by May 18 Dietary restrictions observed, catering provided by Cameron Mitchell Women’s Philanthropy Co-Chairs Jane Bodner & Emily Kandel Lion of Judah Co-Chairs Gigi Fried & Shelly Igdaloff Lion Event Co-Chairs Margie Goldach & Clemy Keidan Questions? Please contact Rachel Gleitman, Director of Women’s Philanthropy at [email protected] This event is open to Lions of Judah and Step Up Lions. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936