James M. Dolliver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

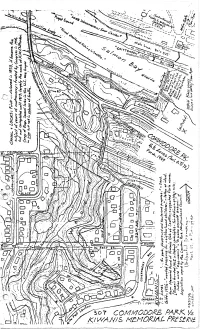

Commodore Park Assumes Its Name from the Street Upon Which It Fronts

\\\\. M !> \v ri^SS«HV '/A*.' ----^-:^-"v *//-£ ^^,_ «•*_' 1 ^ ^ : •'.--" - ^ O.-^c, Ai.'-' '"^^52-(' - £>•». ' f~***t v~ at, •/ ^^si:-ty .' /A,,M /• t» /l»*^ »• V^^S^ *" *9/KK\^^*j»^W^^J ** .^/ ii, « AfQVS'.#'ae v>3 ^ -XU ^4f^ V^, •^txO^ ^^ V ' l •£<£ €^_ w -* «»K^ . C ."t, H 2 Js * -^ToT COMMODOR& P V. KIWAN/S MEMORIAL ru-i «.,- HISTORY: PARK When "Indian Charlie" made his summer home on the site now occupied by the Locks there ran a quiet stream from "Tenus Chuck" (Lake Union) into "Cilcole" Bay (Salmon Bay and Shilshole Bay). Salmon Bay was a tidal flat but the fishing was good, as the Denny brothers and Wil- liam Bell discovered in 1852, so they named it Salmon Bay. In 1876 Die S. Shillestad bought land on the south side of Salmon Bay and later built his house there. George B. McClellan (famed as a Union General in the Civil War) was a Captain of Engineers in 1853 when he recommended that a canal be dug from Lake Washington to Puget Sound, a con- cept endorsed by Thomas Mercer in an Independence Day celebration address the following year which he described as a union of lakes and bays; and so named Lake Union and Union Bay. Then began a series of verbal battles that raged for some 60 years from here to Washington, D.C.! Six different channel routes were not only proposed but some work was begun on several. In §1860 Harvey L. Pike took pick and shovel and began digging a ditch between Union Bay and Lake i: Union, but he soon tired and quit. -

Oregon's Civil

STACEY L. SMITH Oregon’s Civil War The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest WHERE DOES OREGON fit into the history of the U.S. Civil War? This is the question I struggled to answer as project historian for the Oregon Historical Society’s new exhibit — 2 Years, Month: Lincoln’s Legacy. The exhibit, which opened on April 2, 2014, brings together rare documents and artifacts from the Mark Family Collection, the Shapell Manuscript Founda- tion, and the collections of the Oregon Historical Society (OHS). Starting with Lincoln’s enactment of the final Emancipation Proclamation on January , 863, and ending with the U.S. House of Representatives’ approval of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery on January 3, 86, the exhibit recreates twenty-five critical months in the lives of Abraham Lincoln and the American nation. From the moment we began crafting the exhibit in the fall of 203, OHS Museum Director Brian J. Carter and I decided to highlight two intertwined themes: Lincoln’s controversial decision to emancipate southern slaves, and the efforts of African Americans (free and enslaved) to achieve freedom, equality, and justice. As we constructed an exhibit focused on the national crisis over slavery and African Americans’ freedom struggle, we also strove to stay true to OHS’s mission to preserve and interpret Oregon’s his- tory. Our challenge was to make Lincoln’s presidency, the abolition of slavery, and African Americans’ quest for citizenship rights relevant to Oregon and, in turn, to explore Oregon’s role in these cataclysmic national processes. This was at first a perplexing task. -

January 1955

mE PRESID.ENm1S APPOIN TS S Y, J WARY 1, 1955 9•45 12: 20 pn De .... .,. ....... .,, the Off'ic and returned to the Rous • 2:00 part the Hou e went to the Ottiee. 4:00 pn The President d arted the Office and returned to the House, via Mr. Clift berts suite. (Ft avy rains throughout the dq) I J.w.:A.u..u.>;•n'?'' S A? 0 'lie J.5 J. AI 2, 1955 AUGUSTA, GIDRGIA ll.:00 The esid t an - senho er d , rted the Hou nroute to the Rei M orial byterian Church. 11:10 Arri.Ted at t Church. lltlS am Church en:ice began. 12:12 pm The President and l s . Eisenh er d rt4'<1 the Church and returned t o t he l:ouse. 12:19 Jiil An-iv at th Rous • 1:00 The esident t e off wit h the following: • Zig Lannan • Frank lillard r. F.d Dudley 3:50 Completed 18 hol e s. 4140 The lident nd a. s nh P and s. Dou , accompanied by the following, depart, th House enroute to Bush Airti ld. Hr. ClU't Roberts Mr. illiam Robinson • Ellis Slat r • Frank rill.ard Mr. and 11" • Free Go den 5:0; pm Arrived sh Airfi ld d boarded Columbine. 5tl3 J:lll Airborne for ~ e.ahington, D. c. 7:00 pi Arrim HATS Terminal. The Preli.dent and lro. Eisenhower and guest• deplaned. 7:10 pa The President and e. i enh er d s. Do departed the Airport and motored to the ~'hite House. -

Te Western Amateur Championship

Te Western Amateur Championship Records & Statistics Guide 1899-2020 for te 119t Westrn Amatur, July 26-31, 2021 Glen View Club Golf, Il. 18t editon compiled by Tim Cronin A Guide to The Guide –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Welcome to the 119th Western Amateur Championship, and the 18th edition of The Western Amateur Records & Statistics Guide, as the championship returns to the Glen View Club for the first time since the 1899 inaugural. Since that first playing, the Western Amateur has provided some of the best competition in golf, amateur or professional. This record book allows reporters covering the Western Am the ability to easily compare current achievements to those of the past. It draws on research conducted by delving into old newspaper files, and by going through the Western Golf Association’s own Western Amateur files, which date to 1949. A few years ago, a major expansion of the Guide presented complete year-by-year records and a player register for 1899 through 1955, the pre-Sweet Sixteen era, for the first time. Details on some courses and field sizes from various years remain to be found, but no other amateur championship has such an in-depth resource. Remaining holes in the listings will continue to be filled in for future editions. The section on records has been revised, and begins on page 8. This includes overall records, including a summary on how the medalist fared, and more records covering the Sweet Sixteen years. The 209-page Guide is in two sections. Part 1 includes a year-by-year summary chart, records, a special chart detailing the 37 players who have played in the Sweet Sixteen in the 63 years since its adoption in 1956 and have won a professional major championship, and a comprehensive report on the Sweet Sixteen era through both year-by-year results and a player register. -

Walla Walla Pro Fires Final Round 60 to Set Record, Wins Rosauers

PRESORT STD FREE AUGUST U.S. Postage PAID COPY 2017 ISSUE THE SOURCE FOR NORTHWEST GOLF NEWS Port Townsend, WA Permit 262 Spokane and beyond: Golf variety abounds If you head to the Spokane area and into Idaho you will find a terrific variety of golf, including places like Circling Raven in Worley, Idaho (pictured right). The city of Spokane has some great courses and prices as well. For more, see inside this section of Inside Golf Newspaper. Walla Walla pro WHAT’S NEW Whistler: A gem of a NW destination IN NW GOLF fires final round 60 to set record, Myrtle Beach World Am wins Rosauers looks for another big field PGA Professional Brady Sharp of Walla Walla Over 3,000 players will be on hand for the CC (Walla Walla, Wash.) went low in the final 2017 Myrtle Beach World Amateur Golf Cham- round and came from behind to win the Rosauers pionship, set for Aug. 28-31 at some of the best Open Invitational at Indian Canyon Golf Course courses Myrtle Beach has to offer. in Spokane. The tournament features different formats Sharp shot a tournament-record 11-under-par for men, women and seniors with the top players 60 in the third and final round to charge up the from each flight meeting for the championship on leaderboard to win the tournament in a playoff the final day of the tournament. Entry fee for the with Russell Grove of North Idaho College. tournament is $575 and includes four days of tournament golf, nightly functions at the Myrtle The two players finished with totals of 197 Beach Convention Center. -

Preliminary Draft

PRELIMINARY DRAFT Pacific Northwest Quarterly Index Volumes 1–98 NR Compiled by Janette Rawlings A few notes on the use of this index The index was alphabetized using the wordbyword system. In this system, alphabetizing continues until the end of the first word. Subsequent words are considered only when other entries begin with the same word. The locators consist of the volume number, issue number, and page numbers. So, in the entry “Gamblepudding and Sons, 36(3):261–62,” 36 refers to the volume number, 3 to the issue number, and 26162 to the page numbers. ii “‘Names Joined Together as Our Hearts Are’: The N Friendship of Samuel Hill and Reginald H. NAACP. See National Association for the Thomson,” by William H. Wilson, 94(4):183 Advancement of Colored People 96 Naches and Columbia River Irrigation Canal, "The Naming of Seward in Alaska," 1(3):159–161 10(1):23–24 "The Naming of Elliott Bay: Shall We Honor the Naches Pass, Wash., 14(1):78–79 Chaplain or the Midshipman?," by Howard cattle trade, 38(3):194–195, 202, 207, 213 A. Hanson, 45(1):28–32 The Naches Pass Highway, To Be Built Over the "Naming Stampede Pass," by W. P. Bonney, Ancient Klickitat Trail the Naches Pass 12(4):272–278 Military Road of 1852, review, 36(4):363 Nammack, Georgiana C., Fraud, Politics, and the Nackman, Mark E., A Nation within a Nation: Dispossession of the Indians: The Iroquois The Rise of Texas Nationalism, review, Land Frontier in the Colonial Period, 69(2):88; rev. -

Messages of the Governors of the Territory of Washington to the Legislative Assembly, 1854-1889

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLICATIONS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES Volume 12,pp. 5-298 August, 1940 MESSAGES OF THE GOVERNORS OF THE TERRITORY OF WASHINGTON TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, 1854-1889 Edited by CHARLESi\'l.GATES UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 1940 FOREWORD American history in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries is in large part the story of the successive occupation of new areas by people of European antecedents, the planting therein of the Western type of civilization, and the interaction of the various strains of that civilization upon each other and with the environment. The story differs from area to area because of differences not only in the cultural heritage of the settlers and in the physical environment but also in the scientific and technological knowledge available dur- ing the period of occupation. The history of the settlement and de- velopment of each of these areas is an essential component of the history of the American Nation and a contribution toward an under- standing of that Nation as it is today. The publication of the documents contained in this volume serves at least two purposes: it facilitates their use by scholars, who will weave the data contained in them into their fabrics of exposition and interpretation, and it makes available to the general reader a fas- cinating panorama of the early stages in the development of an Amer- ican community. For those with special interest in the State of Washington, whether historians or laymen, the value of this work is obvious; but no one concerned with the social, economic, or diplomatic history of the United States in the second half of the nineteenth century can afford to ignore it. -

Congressional Record-House. J .Anu.Ary 4

- 204 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. J .ANU.ARY 4, $55,000,000 is a threat to the interests of the country, its own history SURVEYOR-GENERAL OF NEVADA. shows that the announcement was unwarranted by its own history and Charles W. Irish, of Iowa Ci~y, Iowa, whowascom;nissioned dnring entirelv uncalled for. the recess of the Senate, to be surveyor-general of Nevada, vice Chris The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. HARRIS in the chair). The Senate topher C. Downing, removed. resumes the consideration of the unfinished business, being the bill (S. llECEIVERS OF PUBLIC MONEYS. 311) to aid in the establishment and temporary support of common schools. Gould B. Blakely, of Sidney, Nebr., who was commissioned during Mr. CULLOl\f. There ought to be a brief executive session this the recess of the Senate, to be receiver of public moneys at Sidney, evening, aud I move that the Senate proceed to the consideration of Nebr., to fill an original vacancy. executive business. Benjamin F. Burch, of Independence, Oregon, who was commissioned Mr. BLAIR. Before that motion is put I should like to say that I during the recess of the Senate, to be receiver of public moneys at shall press the consideration of the unfinished business. Oregon City, Oregon, 'Vice John G. Pillsbury, term expired. The PRESIDING OFFICER. Is the motion withdrawn? Alfred B. Charde, of Oakland, Nebr., who was commissioned during Mr. CULLOM. Only to allow a statement to be made. the recess of the Senate, to be receiver of public moneys at Niobrara, Nebr., vice Sanford Parker, term expired. -

An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 3-14-1997 An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895 Clarinèr Freeman Boston Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Boston, Clarinèr Freeman, "An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895" (1997). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4992. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6868 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice were presented March 14, 1997, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVAL: Charles A. Tracy, Chair. Robert WLOckwood Darrell Millner ~ Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL<: _ I I .._ __ r"'liatr · nistration of Justice ******************************************************************* ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on 6-LL-97 ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice, presented March 14, 1997. -

I a Good Cigar |

10 THE SEATTLE STAR WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 23, 1924 WASHINGTON MAY SEND JACK WESTLAND TO BIG GOLF MEET Washington’s Golf Ace BRITT IS STOPPED BY MORGAN THIRD | IN Take Trip OUR BOARDING HOUSE BY AHERN |Right on Westland Figures to Win Swamped by Chin Wi Coast Title; May Go to National Collegiate Meet |.~ for Champ BY ALEX (~ ROSE Teddies Home With Westland, the crack golfer Romp 'First Time Britt Has Ever JACK Ballard of the University of Washington 35 to 9 Victory; \ Taken the Count; Small and Pacific Coast conference inter Beats West Seattle and Morrow Draw collegiate champion, may be the STANDINGS first representative of the Far West UREF MORGAN won lot Won Lost Yot a of new in the national tournament in college o 1T(;1) ROOMVEIL ccvsavsenssnssneB 1.000 friends last night, the East 0 1.000 Hallard sstsapinsassaesss B { The classy little Coast feather. sidbenesssnssss B 1 " Plans aro now under 'Nnmdnn way to make | welght king showed the '“’vllho-!11c...v.........! I' skeptics who for the winner the possibls of Coast ::; {sald he couldn't hit, that he packs conference meet, which will be RRttt 1 held E s a punch, when he knocked Frankle YT eeSt 000 In Portland at the Waverley club in L F In the 8 .hrm dead third round of th EIRARMIIN s B 0800 -s sas iasviivntns = May. to go to the national tourna- scheduled six-round battls at ment. RESULTS |! Crystal Pool, m Linocein 11, Garfield # And as Westland won the It was the time In honors l Ballard 27, West Neattle 11, first Britt's & year ago and seems to be the class Hoossvell 35, Queen Anne ¥, ring career that he has taken the 1%, Franklin 14, Oof the field agnin, he stunds a fine Broadway | count, chance of being the Western choice i A right hand on the chin turned Roosevelt and Ballard are Three of the golfers in on greatest leading the high school basket zvha trick. -

History of the Kenridge Invitational

HISTORY OF THE KENRIDGE INVITATIONAL A group of men attempted to establish a golf and country club in the Charlottesville/Albemarle County area a number of times before succeeding with Farmington County Club in 1929. Before Farmington, the local alternative was a nine- hole course, “Albemarle Golf Club”, located off of Meade Avenue in Charlottesville. However, the success of Farmington Country Club brought about the demise of Albemarle Golf Club. A 1931 article in ‘Golf Illustrated’ noted that “they” acquired a parcel of land, some one thousand acres, for development of a community and golf course. Fred Findlay received the commission to design the original eighteen-hole venue, which opened in May 1929. Findlay was born in Scotland, and after serving in the British Army spent the rest of his life as an amateur painter and professional golf course architect. Records show that Findlay designed more golf courses in the Commonwealth of Virginia than any other individual. Fred Findlay’s son-in-law, Raymond F. Loving, actually began work on the golf course in early 1927, prior to the official formation of Farmington Country Club. Loving’s effort led to his appointment as the Club’s General Manager, before the golf course was even finished! To serve as Golf Professional, Jack Robertson was hired from The Cascades, and he remained until 1934. Amongst the early Farmington members, Dr. Rice Warren, Dr. M.L. Rea and W. Fritz Souder established themselves in golfing circles. Soon after Farmington’s founding, it joined the Appalachian Golf Association which had existed for some fifteen years. -

Hon. Jack Westland Hon. Frank Thompson

13220 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- SENATE June 9 provisions of section '711, title 10, ot the IN THE NAVY SUPPLY CORPS United States Code. The following named officers of the Navy Harry J.P. Foley, Jr. for temporary promotion to the grade of rear Jack J. Appleby DIPLOMATIC AND FOREIGN SERVICE admiral in the staff corps indicated subject Winston H. SChlee! Clinton E. Knox, of New York, a Foreign to qualification therefor as provided by law: CIVIL ENGINEEil CORPS Service Officer of class 2, to be Ambassador William M. Beaman Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the MEDICAL CORPS DENTAL CORPS United States of America to the Republic of Herbert H. Eighmy Robert 0. Canada, Jr. Joseph L. Yon Horace D. Warden Maurice E. Simpson Dahomey. EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS "On the basis of the party unity record of Dr. Sara Jane Rhoads, Chemistry De Goldwater Outlook: Good Chance for BARRY GoLDWATER's detractors and from what partment, University of Wyoming. Success I've seen and heard among fellow GOP House Dr. Alyea, a professor of chemistry at Members favorable to BARRY, there's tremen dous weight in favor of the opinion that Princeton University for 34 years is EXTENSION OF REMARKS Sena'tor GOLDWATER would enjoy an enthu widely known for his novel lecture ~ble 0 .. siastic welcome on the ticket in Congres and overhead projection demonstrations. sional districts all over the country," the He has developed a new technique called HON. JACK WESTLAND Washington State Congr~sman said. tested overhead projection series OF WASHINGTON "Let's not forget that BARRY GOLDWATER TOPS-a kit of 15 devices with which beat a.