Copyright by Josephine W. Hill 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NGA Retailer Membership List October 2013

NGA Retailer Membership List October 2013 Company Name City State 159-MP Corp. dba Foodtown Brooklyn NY 2945 Meat & Produce, Inc. dba Foodtown Bronx NY 5th Street IGA Minden NE 8772 Meat Corporation dba Key Food #1160 Brooklyn NY A & R Supermarkets, Inc. dba Sav-Mor Calera AL A.J.C.Food Market Corp. dba Foodtown Bronx NY ADAMCO, Inc. Coeur D Alene ID Adams & Lindsey Lakeway IGA dba Lakeway IGA Paris TN Adrian's Market Inc. dba Adrian's Market Hopwood PA Akins Foods, Inc. Spokane Vly WA Akins Harvest Foods- Quincy Quincy WA Akins Harvest Foods-Bonners Ferry Bonner's Ferry ID Alaska Growth Business Corp. dba Howser's IGA Supermarket Haines AK Albert E. Lees, Inc. dba Lees Supermarket Westport Pt MA Alex Lee, Inc. dba Lowe's Food Stores Inc. Hickory NC Allegiance Retail Services, LLC Iselin NJ Alpena Supermarket, Inc. dba Neimans Family Market Alpena MI American Consumers, Inc. dba Shop-Rite Supermarkets Rossville GA Americana Grocery of MD Silver Spring MD Anderson's Market Glen Arbor MI Angeli Foods Company dba Angeli's Iron River MI Angelo & Joe Market Inc. Little Neck NY Antonico Food Corp. dba La Bella Marketplace Staten Island NY Asker's Thrift Inc., dba Asker's Harvest Foods Grangeville ID Autry Greer & Sons, Inc. Mobile AL B & K Enterprises Inc. dba Alexandria County Market Alexandria KY B & R Stores, Inc. dba Russ' Market; Super Saver, Best Apple Market Lincoln NE B & S Inc. - Windham IGA Willimantic CT B. Green & Company, Inc. Baltimore MD B.W. Bishop & Sons, Inc. dba Bishops Orchards Guilford CT Baesler's, Inc. -

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES for a MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY

SAN JOSE Food Works FOOD SYSTEM CONDITIONS & STRATEGIES FOR A MORE VIBRANT RESILIENT CITY NOV 2016 Food Works SAN JOSE Food Works ■ contents Executive Summary 2 Farmers’ markets 94 Background and Introduction 23 Food E-Commerce Sector 96 San Jose Food System Today 25 Food and Agriculture IT 98 Economic Overview 26 Food and Agriculture R & D 101 Geographic Overview 41 Best Practices 102 San Jose Food Sector Actors and Activities 47 Summary of Findings, Opportunities, 116 County and Regional Context 52 and Recommendations Food Supply Chain Sectors 59 APPENDICES Production 60 A: Preliminary Assessment of a San Jose 127 Market District/ Wholesale Food Market Distribution 69 B: Citywide Goals and Strategies 147 Processing 74 C: Key Reports 153 Retail 81 D: Food Works Informants 156 Restaurants and Food Service 86 End Notes 157 Other Food Sectors 94 PRODUCED BY FUNDED BY Sustainable Agriculture Education (SAGE) John S. and James L. Knight Foundation www.sagecenter.org 11th Hour Project in collaboration with San Jose Department of Housing BAE Urban Economics Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority www.bae1.com 1 San Jose Executive Summary What would San Jose look like if a robust local food system was one of the vital frameworks linking the city’s goals for economic development, community health, environmental stewardship, culture, and identity as the City’s population grows to 1.5 million people over the next 25 years? he Food Works report answers this question. The team engaged agencies, businesses, non- T profits and community groups over the past year in order to develop this roadmap for making San Jose a vibrant food city and a healthier, more resilient place. -

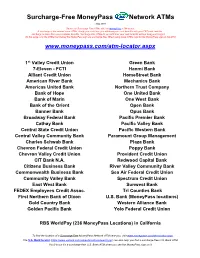

Currently-Participating Cash Access Atms and Stores

Surcharge-Free MoneyPass Network ATMs May 2018 Search for Surcharge-Free ATMs with the MoneyPass ATM locator. A surcharge is the amount some ATMs charge you each time you withdraw your cash benefits with your EBT card, and this surcharge is taken from your available benefits. Surcharge-free ATMs let you withdraw your cash benefits without being surcharged. On this page, only the ATMs that display the MoneyPass sign are surcharge free. When using these ATMs, look for the MoneyPass sign on the ATM. www.moneypass.com/atm-locator.aspx 1st Valley Credit Union Green Bank 7-Eleven - FCTI Hanmi Bank Alliant Credit Union HomeStreet Bank American River Bank Mechanics Bank Americas United Bank Northern Trust Company Bank of Hope One United Bank Bank of Marin One West Bank Bank of the Orient Open Bank Banner Bank Opus Bank Broadway Federal Bank Pacific Premier Bank Cathay Bank Pacific Valley Bank Central State Credit Union Pacific Western Bank Central Valley Community Bank Paramount Group Management Charles Schwab Bank Plaza Bank Chevron Federal Credit Union Poppy Bank Chevron Valley Credit Union Provident Credit Union CIT Bank N.A. Redwood Capital Bank Citizens Business Bank River Valley Community Bank Commonwealth Business Bank Sea Air Federal Credit Union Community Valley Bank Spectrum Credit Union East West Bank Sunwest Bank FEDEX Employees Credit Assoc. Tri Counties Bank First Northern Bank of Dixon U.S. Bank (MoneyPass locations) Gold Country Bank Western Alliance Bank Golden Pacific Bank Yolo Federal Credit Union RBS WorldPay (236 MoneyPass Locations) in California To find the location of a Surcharge-Free MoneyPass Network ATM near you, visit www.moneypass.com/atm-locator.aspx. -

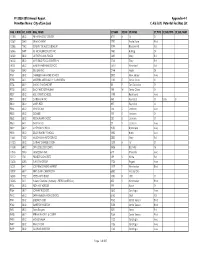

FY 2009-2010 Annual Report Permittee Name: City of San José Appendix 4-1 C.4.B.Iii.(1) Potential Facilities List

FY 2009-2010 Annual Report Appendix 4-1 Permittee Name: City of San José C.4.b.iii.(1) Potential Facilities List ORG_CODE SIC_CODE ORG_NAME ST_NUM ST_DIR ST_NAME ST_TYPE ST_SUB_TYPE ST_SUB_NUM 11385 5812 PIN HIGH GOLF CENTER 4701 N 1st St 13062 3540 3B MACHINING 2292 Trade Zone Blvd 13086 7542 SEVENTY SIX AUTO DETAILING 1099 Blossom Hill Rd 16046 3499 KC METAL PRODUCTS INC 1960 Hartog Dr 16322 5812 LA TROPICANA FOODS 1630 Story Rd 16330 5812 MI PUEBLO FOOD CENTER #4 1745 Story Rd 16331 5812 MARTIN FARNHAM SCHOOL 15711 Woodard Rd 15664 3540 K&H LAB INC 2744 Aiello Dr 9761 5812 CHARLES FANMATRE SCHOOL 2800 New Jersey Ave 9788 5411 MI TIERRA MERCADO Y CARNICERIA 1130 E Santa Clara St 9726 5812 DAKAO SANDWICHES 98 E San Salvador St 9730 5812 DAC-PHUC RESTAURANT 198 W Santa Clara St 9807 5812 HOLY SPIRIT SCHOOL 1198 Redmond Ave 9811 5812 CATERMAN INC 448 Reynolds Cir Suite B 9812 5812 MIKE'S PIZZA 497 Reynolds Cir 9846 5812 TRINE'S CAFE 146 S Jackson Ave 9853 5812 GOMBEI 193 E Jackson St 9862 5812 RESTAURANT KAZOO 250 E Jackson St 9863 5411 SHOP N GO 29 S Jackson Ave 9822 5812 MATHSON SCHOOL 2050 Kammerer Ave 9833 5812 DELOS BAGBY SCHOOL 1850 Harris Ave 11661 7530 MILLENNIUM AUTO SERVICE 2520 Story Rd 11523 5812 CATHAY CHINESE CUISINE 1339 N 1st St 11538 5812 SAN JOSE JOB CORPS 3485 East Hills Dr 11816 3540 TAGDESIGN INC. 619 University Ave 12112 1741 PIONEER CONCRETE 139 S White Rd 13600 5093 TUNG TAI GROUP 1726 Rogers Ave 16257 5411 LOS PRIMOS MEAT MARKET 1539 S Winchester Blvd 15939 5812 KIM'S CAFE-CANDESCENT 6580 Via del Oro 16248 7532 -

Business Overview

Navigating the Supermarket Channel -West Coast US 1 John Rand, SVP October 2016 Regional Grocery Forum - West © Kantar Retail 2016 2 Copyright © Kantar Retail 2016. All Rights Reserved. 501 Boylston St., Suite 6101, Boston, MA 02116 T: +1 (617) 912 2828 [email protected] No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without the express written permission of Kantar Retail. The printing of any copies for backup is also strictly prohibited. Disclaimers The analyses and conclusions presented in this seminar represent the opinions of Kantar Retail. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the retailer(s) under discussion. This seminar is not endorsed or otherwise supported by the management of any of the companies covered during the course of the workshop or within the following slides. © Kantar Retail 2016 3 1 Exploring the West Coast Retail Landscape 2 The Albertsons Companies 3 Zooming In: Regional Focus © Kantar Retail 2016 Retailer Overview 4 Kroger and WinCo leading the race in sales growth rate KR Top West Supermarket Retailers Sales (USD billions) Square Footage (millions) % of West Totals US CAGR Rank CAGR CAGR CAGR 2016E 2016E Retailer 2011 2016E 2021E ('16E- 2011 2016E 2021E 2016E ('11-'16E) ('11-'16E) ('16E-'21E) Sales Sq Ft '21E) Sales 1 Kroger $84.1 $112.6 $140.0 6.0% 4.5% 143.9 171.0 179.3 3.5% 1.0% -

EBT Surcharge-Free Atms

EBT Surcharge-Free ATMs A surcharge is the amount some ATMs charge you each time you withdraw your cash benefits, and this surcharge is deducted from your available balance. Surcharge-free ATMs provide you access to your cash benefits without being surcharged by the ATM. March 13, 2014 Alta One Federal Credit Union (NEA-WEA) America’s Christian Credit Union Argent Bank Arrowhead Credit Union Banco Popular Bank of Commerce Bank of Rio Vista Bank of the West Bay Federal Credit Union CBC Federal Credit Union Citibank Comerica Edwards Federal Credit Union Exchange Bank Financial Center Credit Union First Bank & Trust Kern Schools Federal Credit Union Mission Community Bank North Valley Bank NuVision Federal Credit Union Plumas Bank Priority One Credit Union Redwood Credit Union River City Bank Sacramento Credit Union San Diego County Credit Union SchoolsFirst Federal Credit Union Sun Community Federal Credit Union U.S. Bank * United Security Bank USE Credit Union Valley Business Bank XCeed Financial Credit Union Safeway (Cardtronics) Von’s (Cardtronics) *Use the U.S. Bank locator to find a surcharge-free ATM near you. Surcharge-Free MoneyPass ATMs Not all ATMs at the following locations are surcharge free – only the MoneyPass ATMs are surcharge free. Look for the MoneyPass sign on the ATM, and use the MoneyPass ATM locator to find a surcharge-free ATM near you. 1st Valley Credit Union Alliance Credit Union Alliant Credit Union American River Bank American Security Bank Americas United Bank American West Bank Bank of Marin Bank of the Orient -

<All City of Gilroy Commercial and Apartment Business Licenses>

<All City of Gilroy Commercial and Apartment Business Licenses> Date: 3/6/2017 Bus# Business Name Owner Name Phone# Number Address Line 1 City St Zip Code Business Products Date Est NAICS SIC 5276 ST MARY CATHOLIC PARISH ROMAN CATHOLIC BISHOP OF SAN(408)847-5151 J 11 1ST ST GILROY CA 95020-5128 CHURCH 01/23/04 813110 8661 13726 THE WAX STUDIO ZUNIGA, MARYLOU (408) 612-5185 66 1ST ST STE 2 GILROY CA 95020-5140 WAX & ESTHETICS SERVICES01/08/15 33999 3999 12302 THERAPEUTIC MASSAGE VASQUEZ, PIERRETTE (408) 607-3180 66 1ST ST STE 3 GILROY CA 95020 MASSAGE THERAPY05/16/13 13295 VERITAS POLYGRAPH EXAMINATIONS GONZALEZ, MICHELLE A. (408) 767-8515 66 1ST ST STE 5 GILROY CA 95020-5140 POLYGRAPH 06/09/14 561611 7381 13135 CALIMEX AUTO INSURANCE SERVICES ROCHA, ALEX (408) 469-9832 66 1ST ST STE 7 GILROY CA 95020-5140 INSURANCE AUTO SALES/NOTARY04/01/14 524210 6411 13546 INFORMED CHOICES INFORMED CHOICES (408) 847-8880 66 1ST ST STE A GILROY CA 95020-5140 PREGNANCY RESOURCE10/08/14 CENTER 10859 SOUTH VALLEY BUSINESS SERVICES MATTEUCCI, CARLA (408) 887-0905 66 1ST ST STE B GILROY CA 95020-5140 TAXES & NOTARY SERVICES07/01/11 541213 7291 1010 EDNA M. DOWELL L M F C HOLCOME, EDNA M (408)847-2120 66 1ST ST STE C GILROY CA 95020-5140 FAMILY SOCIAL SERVICES11/03/94 621330 8049 10853 BANISTER CERTIFIED HAND THERAPY INCBANISTER CERTIFIED HAND THERAPY(408) 712-4669INC 190 1ST ST GILROY CA 95020 PHYSICAL THERAPY/HAND08/01/11 621340 8049 1405 CARAVELLE WORLD TRAVEL PINHEIRO, AL (408)842-0200 190 1ST ST GILROY CA 95020-5129 TRAVEL AGENCY 03/19/91 561510 4724 6247 GURRIES ENTERPRISES RONALD J. -

Vallejo Chase Bank Turner Pkwy Pulse 972 Admiral Callaghan 109 Plaza Dr

ATM An ATM is a cash machine found at banks, stores and many other places that allows you to get your cash benefits. 7-11 - #16743 7-11 #16640 1095 Magazine Street 26 Rio Del Mar $2.95 Surcharge $2.95 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit $300 Transaction Limit 7-11 - #14133 7-11 - #14148 2835 Georgia Street 2580 Springs Road $2.95 Surcharge $2.95 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit $300 Transaction Limit 7-11 - AMEX ADS 1208 Tennessee Street Independent $2.95 Surcharge 1247 Georgia St. $300 Transaction Limit $3.00 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit Admiral Callag-6 Albertsons Independent ATM 1740 Tuolumne 708 Admiral Callaghan Ln $2.00 Surcharge $3.00 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit $300 Transaction Limit AMF #610 Amigos Market 1100 Petaluma Blvd 2901 Sonoma Blvd $3.00 Surcharge $3.00 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit $300 Transaction Limit Arco AM/PM Val-7 ATM Express 333 Curtola Pkwy Star $2.00 Surcharge 701 Mini Drive $300 Transaction Limit $3.00 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit ATM Express B&B Liquor NYCE 1813 Spring Road 2707 Sonoma Blvd $2.00 Surcharge $2.00 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit $300 Transaction Limit Bank of America Bank of America Springstowne 200 Georgia Street 21 Springstowne Shopping Center $3.00 Surcharge $3.00 Surcharge $1,000 Transaction Limit $1,000 Transaction Limit Bank of the West BEMM INC. 4300 Sonoma Blvd 1300 Sonoma Blvd No Surcharge $3.00 Surcharge $500 Transaction Limit $300 Transaction Limit Ben's Food & Liquor 134721 Best Buy 686 Benicia Road 1182 Admiral Callaghan Ln $3.00 Surcharge $3.00 Surcharge $300 Transaction Limit $300 Transaction Limit Bonfare Market 7 Bonfare Market 8 Independent ATM Independent ATM 2240 Sacramento St. -

Produce Business August 2013

DOLE Fruit_Ad 7/30/13 11:33 AM Page 1 TOC_Layout 1 8/14/13 6:24 PM Page 1 AUG. 2013 • VOL. 29 • NO. 08 • $9.90 p.34 p.66 34 PREPARING FOR PRIME TIME TAILGATING ACTION Produce has become the prevalent headliner at tailgate parties and other grilling events because of its versatility in recipes, simplicity in preparation, ease of portability and, of course, its fresh taste. 21 25TH ANNUAL MARKETING EXCELLENCE AWARDS 40 WASHINGTON APPLE INDUSTRY CONTINUES NEW PLANTINGS Twelve companies are recognized for Exploring unique varieties on the horizon. their outstanding creativity, comprehensive strategy and 49 BUMPER CROP BRINGS OPPORTUNITY FOR CALIFORNIA GRAPES successful execution. A California grape bonanza is underway, and the industry jockeys for position to capitalize on the available opportunities. 8 THE FRUITS OF THOUGHT MERCHANDISING REVIEWS Sysco’s San Francisco Food Safety Failure Reflects On Industry’s Broader Problem 66 Onions – New Ways To Sell An Old Favorite With KPI’s Onions grace consumers’ tables in everything from soups, sauces and salads to sandwiches and much more. The widespread popularity of this versatile vegetable has made it a steady winner for 85 RETAIL PERSPECTIVE retailers. Intelligent Risk-Taking 76 Mushrooms As Moneymakers 86 EUROPEAN MARKET Retailers properly merchandising Tackling Global Food Waste mushrooms will see the money follow and shrink disappear. 88 VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY The Promise Of Biotechnology DRIED FRUIT AND NUTS 83 Raisins Push Impulse Envelop When Promoted In Produce Produce retailers hold the key to a new 4 THE QUIZ revolution of raisin sales. 6 WASHINGTON GRAPEVINE 10 PRODUCE WATCH 18 FROM THE PAGES OF THE PERISHABLE PUNDIT p.30 14 TRADE SHOW CALENDAR Do Consumers Eat More When Given Calorie Recommendations At Restaurants? ‘McDonald’s Study’ Demonstrates Nanny-Statism May Have Unintended Consequences 16 RESEARCH PERSPECTIVES 30 NEWPORT AVENUE MARKET An independent grocer in Central Oregon thrives 17 COMMENTS AND ANALYSIS on community emphasis on wellness and healthy living. -

Powerpoint Template 2007-2010

CRAFT BEER CONSUMERS: WHO ARE THEY, WHERE ARE THEY, AND WHAT ABOUT THE FUTURE? Danny Brager – SVP Beverage Alcohol Practice November 21, 2014 NIELSEN MEASURES WHAT PEOPLE WATCH & BUY BUY WATCH 2 CopyrightThe Nielsen ©2012 Company.Confidential and proprietary. Retail Sales Consumer Insights CopyrightThe Nielsen ©2012 Company.Confidential and proprietary. •1MM HH’s representative of $35B U.S. geographically and 1.6B cases* demographically •Food, Drug, Convenience •Walmart, Target •Ongoing purchase data $14B •Sam’s, BJ’s •Geo-demographic 179MM cases* •Dollar segmentation •Military Exchanges •Fast/flexible $12B •Variety of Liquor markets consumer surveys 75M cases* and accounts across U.S. Source: : Nielsen Total U.S. xAOC + Conv + Liquor + Military; 52 weeks thru 9-13-2014 * Beer is 288 oz case; wine and spirits are Eq 9L cases 3 OUR FOCUS TODAY – THE “WHO” 4 CopyrightThe Nielsen ©2012 Company.Confidential and proprietary. CRAFT BEER CONSUMERS: WHO ARE THEY, WHERE ARE THEY, AND WHAT ABOUT THE FUTURE? 1 CRAFT BEER IN THE BIGGER PICTURE 2 WHO IS BUYING CRAFT BEER? • WHY AND WHERE? • HOW IS THAT CHANGING? • WHAT ARE SOME KEY OPPORTUNITY AREAS? 3 “WHERE” IN SEARCH OF THE “WHO” CRAFT BEER IN THE BIGGER PICTURE CRAFT BEER IS A BRIGHT AND SHINY STAR FOR MULTI-CATEGORY RETAILERS All Nielsen Categories CopyrightThe Nielsen ©2012 Company.Confidential and proprietary. Growing Declining Volume Basis VOLUME DOLLARS 35% ALL CATEGORIES -0.1% +1.4% BEER* +/-0% +3.0% 65% CRAFT BEER +12.5% +16.8% * Beer incl. FMB, Ciders Source: Nielsen Scantrack - Total U.S. – All Outlets Combined ; 52 w/e 10-25-2014 versus prior year; UPC-coded; 127 categories Beer: 52 w/e 10-11-2014; Nielsen measured all outlets (Food, Drug, Mass, Walmart, Club, Dollar, Liquor, Conv, Military) 7 WINE/SPIRITS HAS BEEN WINNING THE BEV AL WARS Share of Beverage Alcohol - # Drinks* 2002 2007 CopyrightThe Nielsen ©2012 Company.Confidential and proprietary. -

Co-Op Grocery Stores and the Triple Bottom Line: for the Workers, for the Community, for the Environment

Co-op Grocery Stores and the Triple Bottom Line: For the Workers, For the Community, For the Environment Allison Riemer Urban and Environmental Policy Senior Comprehensive Occidental College April 2010 Riemer 2 Acknowledgements I thank Patrick Reagan, Dana Harvey, Bruce Palma, David Lippman, Gordon Edgar, Terry Bowling, Stuart Reid, Tracey Giang, Luis Sierra, Quinton Sankofa and the Mandela Marketplace Youth Team. I wish to thank Martha Matsuoka, Robert Gottlieb, and Peter Dreier for their advice on this paper, and the past three years of urban and environmental policy courses that shaped this paper. Thank you Sylvia Chico, Zoë Phillips, Alexa Delwiche, and the staff of UEPI for helping with aspects of my research and supporting my topic. I thank my parents, Becky and Kirk Riemer, and my friends, for always supporting me. Riemer 3 Table of Contents Glossary p. 4 Executive Summary p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction to Food Issues p. 7 Chapter 2: Background Information on Grocery Issues p. 10 Chapter 3: Background on Co-ops and Their History p. 13 Chapter 4: Methodology p. 23 Chapter 5: Case Studies p. 24 I. Thorough Studies p. 25 II. Highlights from Other Stores p. 48 III. Cooperative and Grocery Access Supporters p. 53 Chapter 6: Overall Co-op Issues and Themes p. 63 Chapter 7: Conclusions and Recommendations p. 65 References p. 70 Appendix p. 76 Survey Tool Summary of Survey Results Interview Questions Riemer 4 Glossary Natural foods: There is no concrete or legal definition of natural foods. I will use this term because it is commonly used and it can be described a range of food characteristics. -

SBN 87908) Robert G

1 Heinz Binder (SBN 87908) Robert G. Harris (SBN 124678) 2 Roya Shakoori (SBN 236383) BINDER & MALTER, LLP 3 2775 Park Avenue Santa Clara, CA 95050 4 Tel: (408) 295-1700 Fax: (408) 295-1531 5 Email: [email protected] 6 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 7 Attorneys for Debtor and Debtor-in-Possession 8 MI PUEBLO SAN JOSE, INC. 9 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 10 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 SAN JOSE DIVISION 12 13 In re: Case No. 13-53893-ASW 14 MI PUEBLO SAN JOSE, INC., Chapter 11 15 Debtor. 16 Date: May 22, 2014 Time: 2:15 p.m. 17 Place: Courtroom: 3020 18 280 South First Street San Jose, CA 95113 19 Judge: Hon. Arthur S. Weissbrodt 20 NOTICE OF FILING OF AMENDED EXHIBITS TO THE PLAN SUPPLEMENT 21 FOR THE DEBTOR’S FIRST AMENDED PLAN OF REORGANIZATION PURSUANT TO CHAPTER 11 OF THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY CODE 22 TO ALL CREDITORS ENTITLED TO LIMITED NOTICE, SPECIAL NOTICE, AND 23 THE UNITED STATES TRUSTEE On April 25, 2014, Mi Pueblo San Jose, Inc. the debtor and debtor in possession herein 24 25 (“Mi Pueblo” or the “Debtor”) filed the Debtor’s First Amended Plan of Reorganization 26 Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code [Docket No. 739] (as altered, modified, or 27 supplemented from time to time, the “Plan”). On May 1, 2014, Mi Pueblo filed its Plan 28 NOTICE OF FILING OF AMENDED EXHIBITS Page 1 Case: 13-53893 Doc# 894 Filed: 05/16/14 Entered: 05/16/14 15:15:06 Page 1 of 2 1 Supplement to Debtor’s First Amended Plan of Reorganization Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the 2 Bankruptcy Code [Docket No.