Transfer and Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Teachers' Pay in Ancient Greece

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska 5-1942 Teachers' Pay In Ancient Greece Clarence A. Forbes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Teachers' Pay In Ancient Greece * * * * * CLARENCE A. FORBES UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA STUDIES Ma y 1942 STUDIES IN THE HUMANITIES NO.2 Note to Cataloger UNDER a new plan the volume number as well as the copy number of the University of Nebraska Studies was discontinued and only the numbering of the subseries carried on, distinguished by the month and the year of pu blica tion. Thus the present paper continues the subseries "Studies in the Humanities" begun with "University of Nebraska Studies, Volume 41, Number 2, August 1941." The other subseries of the University of Nebraska Studies, "Studies in Science and Technology," and "Studies in Social Science," are continued according to the above plan. Publications in all three subseries will be supplied to recipients of the "University Studies" series. Corre spondence and orders should be addressed to the Uni versity Editor, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. University of Nebraska Studies May 1942 TEACHERS' PAY IN ANCIENT GREECE * * * CLARENCE A. -

ANGELS in ISLAM a Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl

ANGELS IN ISLAM A Commentary with Selected Translations of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al- malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels) S. R. Burge Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2009 A loose-leaf from a MS of al-Qazwīnī’s, cAjā’ib fī makhlūqāt (British Library) Source: Du Ry, Carel J., Art of Islam (New York: Abrams, 1971), p. 188 0.1 Abstract This thesis presents a commentary with selected translations of Jalāl al-Dīn cAbd al- Raḥmān al-Suyūṭī’s Al-Ḥabā’ik fī akhbār al-malā’ik (The Arrangement of the Traditions about Angels). The work is a collection of around 750 ḥadīth about angels, followed by a postscript (khātima) that discusses theological questions regarding their status in Islam. The first section of this thesis looks at the state of the study of angels in Islam, which has tended to focus on specific issues or narratives. However, there has been little study of the angels in Islamic tradition outside studies of angels in the Qur’an and eschatological literature. This thesis hopes to present some of this more general material about angels. The following two sections of the thesis present an analysis of the whole work. The first of these two sections looks at the origin of Muslim beliefs about angels, focusing on angelic nomenclature and angelic iconography. The second attempts to understand the message of al-Suyūṭī’s collection and the work’s purpose, through a consideration of the roles of angels in everyday life and ritual. -

Óscar Perea Rodríguez Ehumanista: Volume 6, 2006 237 Olivera

Óscar Perea Rodríguez 237 Olivera Serrano, César. Beatriz de Portugal. La pugna dinástica Avís-Trastámara. Prologue by Eduardo Paro de Guevara y Valdés. Santiago de Compostela: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas-Xunta de Galicia-Instituto de Estudios Gallegos “Padre Sarmiento”, 2005 (Cuadernos de Estudios Gallegos, Anexo XXXV), págs. 590. ISBN 84-00-08343-1 Reviewed by Óscar Perea Rodríguez University of California, Berkeley In his essays, Miquel Batllori often argued that scholars researching Humanism should pay particular attention to the 15th century in order to gain a better understanding of the 16th century. This has been amply achieved by César Olivera Serrano, author of the book reviewed here, for in it he has offered us remarkable insight into 15th-century Castilian history through an extraordinary analysis of 14th-century history. As Professor Pardo de Guevara points out in his prologue, this book is an in-depth biographical study of Queen Beatriz of Portugal (second wife of the King John I of Castile). Additionally, it is also an analysis of the main directions of Castilian foreign policy through the late 14th and 15th centuries and of how Castile’s further political and economic development was strictly anchored in its 14th-century policies. The first chapter, entitled La cuestionada legitimidad de los Trastámara, focuses on Princess Beatriz as the prisoner of her father’s political wishes. King Ferdinand I of Portugal wanted to take advantage of the irregular seizure of the Castilian throne by the Trastámara family. Thus, he offered himself as a candidate to Castile’s crown, sometimes fighting for his rights in the battlefield, sometimes through peace treatises. -

Divine Principle & Angels (V1.6)

Divine Principle & Angels Introduction v 1.6 Recense of an Angel Artist Benny Andersson Introduction • This is an attempt to collect what the Bible and Divine Principle and True Father has spoken about Angels. • Included is some folklore from the Unif. movement. You decide what’s true. Background • The word angel in English is a blend of Old English engel (with a hard g) and Old French angele. Both derive from Late Latin angelus "messenger of God", which in turn was borrowed from Late Greek ἄγγελος ángelos. According to R. S. P. Beekes, ángelos itself may be "an Oriental loan, like ἄγγαρος ['Persian mounted courier']." • Angels, in a variety of religions, are regarded as spirits. They are often depicted as messengers of God in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles and the Quran. • Daniel is the first biblical figure to refer to individual angels by name, mentioning Gabriel (God's primary messenger) in Daniel 9:21 and Michael (the holy fighter) in Daniel 10:13. These angels are part of Daniel's apocalyptic visions and are an important part of all apocalyptic literature Orthodox icon from Saint Catherine's Monastery, representing the archangels Michael and Gabriel. Along with Rafael counted as archangels of Jews, Christians and Muslims. • The conception of angels is best understood in contrast to demons and is often thought to be "influenced by the ancient Persian religious tradition of Zoroastrianism, which viewed the world as a battleground between forces of good and forces of evil, between light and darkness." One of these "sons of God" is "the satan", • a figure depicted in (among other places) the Book of Job. -

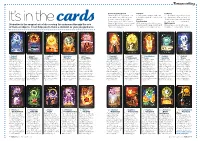

Fortune Telling

Fortune telling How to use the spread Intuition Dowsing Relax and focus on the question Slowly open your eyes and then Using a pendulum, ask it to show you want to ask - this can be as select the card that you feel most you a movement for ‘yes’ and ‘no’. general or specific as you like. drawn to. Then hover it over each card until It’s in the Then, using one of the following Psychometry you get a ‘yes’ - this is your card. forms of divination, choose a card With your eyes closed, run your Bibliomancy Divination is the magical art of discoveringcards the unknown through the use and read the summary you have hand across the page and stop at Close your eyes and with your of tools or objects. It can help you to make a decision or give you guidance chosen for guidance. the card you feel is right for you. finger point to any card at random. Gabriel Hanael Jophiel Metatron Uriel Zaphkiel Jophiel Sandalphon Zadkiel Gabriel 1 Balance 2Willpower 3 Joy 4 Miracles 5 Friendship 6 Surrender 7 Forgiveness 8 Love 9 Security 10 Grace Gabriel wants you to The great whales of The card you have Miracles are changes Uriel wishes you to The angels want you to Jophiel asks you to let This angelic oracle The angels unite The oracle of Gabriel know that you have the oceans deep are chosen brings forth a of perception and know that the true know that you are go of the pain of the comes to you as with their powerful wishes you to receive been too busy. -

Roman Life in Cyrenaica in the Fourth Century As Shown in the Letters of Synesius, Bishop of Ptolemais

920 T3ee H. C. Thory Roman Life in Cyrenaica in the Fourth Century as Shown in the Letters of 5y nesius, , Si shop of Ptolernais ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY AS SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PTOLEMAIS BY t HANS CHRISTIAN THORY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS IN CLASSICS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1920 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 7 20 , 19* THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Chrifti^„.T^ i2[ H^.s.v t : , , ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY ENE Af*111rvi'T TLEDT?rt A? SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PTQLEMAIS IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF ^3 Instructor in Charge Approved HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF ,£M?STCS. CONTENTS Page I. Cyrenaica: the Country and its Hiatory 1 II. The Barbarian Invasions.. 5 III. Government: Military and Civil 8 IV. The Church 35 V. Organization of Society 34 VI. Agriculture Country Life 37 vii, Glimpses of City Life the Cities 46 VIII. Commerce Travel — Communication 48 IX. Language — • Education Literature Philosophy Science Art 57 X. Position of Women Types of Men 68 Bibliography 71 ********** 1 ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY AS SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PT0LEMAI8 I CYRENAICA: THE COUNTRY AND ITS HISTORY The Roman province of Cyrenaioa occupied the region now called Barca, in the northeastern part of Tripoli, extending eaet from the Greater Syrtis a distance of about 20C miles, and south from the Mediterranean Sea a distance of 70 to 80 miles. -

Archangel Kindle

ARCHANGEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sharon Shinn | 10 pages | 01 Dec 1997 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780441004324 | English | New York, United States Archangel PDF Book She has a great love of nature, people, and the planet, and she enjoys her connection in spirit, both here and in heaven. The energy of the mouse is quiet productivity of the multitudes, while the groundhog digs deeper for answers and represents the world of dreams, the opossum represents family nurturing, and the skunk and raccoon represent the cleanup crew. Any time you or someone you love is experiencing sadness due to loneliness, call on Archangel Uriel to help to see the wonders that exist within your soul or the soul for whom you are praying. Know that the reality, is there are far more Archangels serving behind the scenes. Michael the Archangel. Become a fundraiser to help us collect, clone, archive the genetics, and replant these important trees for future generations. These cookies do not store any personal information. In this book I provide many guided meditations audio and experiments that help you discover more ways to deeply connect with Michael. In human form, Raquel appears with wings in flowing white robes and a large book in hand. Additionally, this Archangel symbolically appears in the form of fish, representing the fluidity of divine communications, situations of divine emotional importance, and the surreal world of dreams. Moscow Official as Yakov Rafalson. External Reviews. Uriel presents three impossible riddles to show us how humans cannot fathom the ways of God. Archangel Jophiel provides assistance with refocusing on positive experiences of life, encouraging inner journeys which lead to the discovery of soul-specific solutions for your life's passions, and raising your energy levels and thoughts toward the light to inspire the giving and receiving of unconditional love. -

Il Tro Vatore

Il trovatore Giuseppe Verdi Il trovatore Giuseppe Verdi Giuseppe Verdi 1813-1901 Òpera en quatre actes amb llibret en italià de Salvatore Cammarano. Estrenada al teatre Apollo de Roma el 19 de gener de 1853. Darrera representació al Teatre Principal del Palma el 22 de maig de 2012. MAIG Dimecres 26 19 hores Divendres 28 19 hores Diumenge 30 18 hores i streaming Durada Primera part: 75 minuts Actes I i II Descans: 20 minuts Segona part: 70 minuts Actes III i IV Producció escènica del Teatro Villamarta de Jerez En dos mots En dos Amb Il trovatore, Giuseppe Verdi (Roncole, 1813 – Milà, 1901) arriba a un dels punts culminants de la seva carrera. La veracitat dramàtica i l’aprofundiment psicològic dels personatges s’accentuen i passen a un primer pla escènic. Tot plegat a Verdi li coincideix amb un moment d’esplendor i maduresa personal. Acaba de complir els 40 anys i se’n va a viure amb Giuseppina Strepponi, una reconeguda soprano amb qui es casaria en secret anys després, el 1859. Estrenada el 1853, Il trovatore comparteix amb La traviata, estrenada el mateix any, i Rigoletto, estrenada dos anys abans, el que s’ha anomenat la “trilogia popular”, tres òperes que tenen en comú el fet de posar el focus en la psicologia dels personatges per deixar un poc de banda temes patriòtics o socials, com s’esdevé a òperes com Nabucco. El llibretista Salvatore Cammarano es va inspirar en l’obra El trovador, del dramaturg espanyol Antonio García Gutiérrez, per escriure aquesta òpera. Si s’ha d’etiquetar, podem dir que Il trovatore és un drama romàntic convencional, o almenys més convencional que els altres dos títols de la trilogia. -

College of Letters 1

College of Letters 1 Kari Weil BA, Cornell University; MA, Princeton University; PHD, Princeton University COLLEGE OF LETTERS University Professor of Letters; University Professor, Environmental Studies; The College of Letters (COL) is a three-year interdisciplinary major for the study University Professor, College of the Environment; University Professor, Feminist, of European literature, history, and philosophy, from antiquity to the present. Gender, and Sexuality Studies; Co-Coordinator, Animal Studies During these three years, students participate as a cohort in a series of five colloquia in which they read and discuss (in English) major literary, philosophical, and historical texts and concepts drawn from the three disciplinary fields, and AFFILIATED FACULTY also from monotheistic religious traditions. Majors are invited to think critically about texts in relation to their contexts and influences—both European and non- Ulrich Plass European—and in relation to the disciplines that shape and are shaped by those MA, University of Michigan; PHD, New York University texts. Majors also become proficient in a foreign language and study abroad Professor of German Studies; Professor, Letters to deepen their knowledge of another culture. As a unique college within the University, the COL has its own library and workspace where students can study together, attend talks, and meet informally with their professors, whose offices VISITING FACULTY surround the library. Ryan Fics BA, University of Manitoba; MA, University of Manitoba; PHD, Emory -

A N G E L S (Amemjam¿) 1

A N G E L S (amemJam¿) 1. Brief description 2. Nine orders of Angels 3. Archangels and Other Angels 1. Brief description of angels * Angels are spiritual beings created by God to serve Him, though created higher than man. Some, the good angels, have remained obedient to Him and carry out His will. Lucifer, whose ambitions were a distortion of God's plan, is known to us as the fallen angel, with the use of many names, among which are Satan, Belial, Beelzebub and the Devil. * The word "angelos" in Greek means messenger. Angels are purely spiritual beings that do God's will (Psalms 103:20, Matthew 26:53). * Angels were created before the world and man (Job 38:6,7) * Angels appear in the Bible from the beginning to the end, from the Book of Genesis to the Book of Revelation. * The Bible is our best source of knowledge about angels - for example, Psalms 91:11, Matthew 18:10 and Acts 12:15 indicate humans have guardian angels. The theological study of angels is known as angelology. * 34 books of Bible refer to angels, Christ taught their existence (Matt.8:10; 24:31; 26:53 etc.). * An angel can be in only one place at one time (Dan.9:21-23; 10:10-14), b. Although they are spirit beings, they can appear in the form of men (in dreams – Matt.1:20; in natural sight with human functions – Gen. 18:1-8; 22: 19:1; seen by some and not others – 2 Kings 6:15-17). * Angels cannot reproduce (Mark 12:25), 3. -

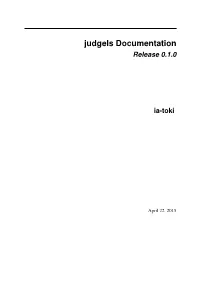

Judgels Documentation Release 0.1.0

judgels Documentation Release 0.1.0 ia-toki April 22, 2015 Contents 1 Introduction1 1.1 Applications...................................1 1.2 License......................................2 1.3 Contributions...................................2 2 Setup 3 2.1 Requirements...................................3 2.2 Installation....................................4 2.3 Configuration...................................4 3 Single Sign On (Jophiel)5 3.1 Configuration...................................5 3.2 Running Jophiel.................................5 3.3 Jophiel User Roles................................5 3.4 Single Sign On Protocol.............................6 3.5 Future Target...................................6 4 Programming Repository (Sandalphon)7 4.1 Configuration...................................7 4.2 Running Sandalphon...............................7 4.3 Sandalphon User Roles..............................8 4.4 Client’s Problem Rendering...........................8 4.5 Future Target...................................8 5 Problem Types9 5.1 Blackbox Grading................................9 5.2 Constraints....................................9 5.3 Evaluators....................................9 5.4 Problem Types.................................. 10 5.5 Creating Checker................................. 11 6 Message Oriented Middleware (Sealtiel) 13 6.1 Configuration................................... 13 6.2 Running Sealtiel................................. 13 6.3 Message Queue.................................. 13 i 6.4 Polling.....................................