Read Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

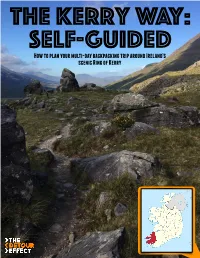

The Kerry Way Self Guided | Free Download

The Kerry Way: Self-Guided How to plan your multi-day backpacking trip around Ireland’s scenic Ring of Kerry Many are familiar with the beautiful Ring of Kerry in County Kerry, Ireland, but far fewer are aware that the entire route can be walked instead of driven. Despite The Kerry Way’s status as one of the most popular of Ireland’s National Waymarked Trails, I had more difficulty finding advice to help me prepare for it than I did for hikes in Scotland and the United Kingdom. At approximately 135 miles, it’s also the longest of Ireland’s trails, and in retrospect I’ve noticed that many companies who offer self-guided itineraries actually cut off two whole sections of the route - in my opinion, some of the prettiest sections. In honor of completing my own trek with nothing but online articles and digital apps to guide the way, I thought I’d pay it forward by creating my own budget-minded backpacker’s guide (for the WHOLE route) so that others might benefit from what I learned. If you prefer to stay in B&Bs rather than camping or budget accommodations, I’ve outlined how you can swap out some of my choices for your own. Stats: English Name: The Kerry Way Irish Name: Slí Uíbh Ráthaigh Location: Iveragh Peninsula, County Kerry, Ireland Official Length: 135 miles (217 km), but there are multiple route options Completion Time: 9 Days is the typical schedule High Point: 1,263ft (385m) at Windy Gap, between Glencar and Glenbeigh Route Style: Circular Loop Table of Contents: (Click to Jump To) Preparedness: Things to Consider Weather Gear Amenities Currency Language Wildlife Cell Service Physical Fitness Popularity Waymarking To Camp or Not to Camp? Emergencies Resources Getting There // Getting Around Route // Accommodations Preparedness: Things to Consider WEATHER According to DiscoveringIreland, “the average number of wet days (days with more than 1mm of rain) ranges from about 150 days a year along the east and south-east coasts, to about 225 days a year in parts of the west.” Our route along the Iveragh Peninsula follows the southwest coast of Ireland. -

Valentia Island Development Company

Valentia Transatlantic Cable Foundation Presentation March 9th 2021 1 Valentia Transatlantic Cable Foundation Meeting with the Cable Station Neighbours March 9th 2021 The Cable Station – Innovation Hub, Visitor Experience and the UNESCO goal Agenda 7.30pm Welcome, Introductions and Context – Leonard Hobbs 7.35pm The journey to date – Mary Rose Stafford 7.45pm UNESCO submission and process – Michael Lyne 7.55pm Roadmap – Leonard Hobbs 8.00pm Q&A 8.30pm Close • How to engage going forward • Future meetings The Gathering 2013 4 Professor Al Gillespie chats with Canadian Ambassador to Ireland Mr Kevin Vickers at the 150th celebrations on Valentia in July 2016 Valentia Transatlantic Cable Foundation 2016 6 Transatlantic Cable Foundation Board 2016 Vision We have ambitious plans to restore the key historical sites on the island to their former glory and to create a place which recalls the wondrous technological achievements of a time past while driving opportunities for Valentia in the future. Successful outcomes of this project will - Preserve our heritage - Complete a UNESCO World Heritage Application - Create and support local employment and enterprise The ‘Valentia Lecture and Gala dinner’ series is launched in 2017 to draw national attention to the project and engage the local community Professor Jeffrey Garten of Yale University with Martin Shanahan, CEO of IDA at the Inaugural Valentia Lecture, July 2017 in the Cable Station Jeffrey Garten “ the notion to me that this wouldn't be a UNESCO site is absurd “ 8 Published December 2017 Published -

Master Dl Map Front.Qxd

www.corkkerry.ie www.corkkerry.ie www.corkkerry.ie www.corkkerry.ie www.corkkerry.ie www.corkkerry.ie www onto log or fice of .ie .corkkerry Full listing available every week in local newspapers. local in week every available listing Full power surfing, diving, sailing, kayaking, sailing, diving, surfing, explored, it is no surprise that that surprise no is it explored, Listowel Classic Cinema Classic Listowel 068 22796 068 Tel: information on attractions and activities, please visit the local tourist information tourist local the visit please activities, and attractions on information marinas and some of the most spectacular underwater marine life to be to life marine underwater spectacular most the of some and marinas Tralee: 066 7123566 www.buseireann.ie 7123566 066 Tralee: seats. el: Dingle Phoenix Dingle 066 9151222 066 T Dingle Leisure Complex Leisure Dingle Rossbeigh; or take a turn at bowling at at bowling at turn a take or Rossbeigh; . For further For . blue flag beaches flag blue ferings at hand. With 13 of Ireland's Ireland's of 13 With hand. at ferings and abundance of of of abundance Killarney: 064 30011 064 Killarney: Bus Éireann Bus travelling during the high season or if you require an automatic car or child or car automatic an require you if or season high the during travelling Tralee Omniplex Omniplex Tralee 066 7127700 7127700 066 Tel: Burke's Activity Centre's Activity Burke's Cave Crag crazy golf in golf crazy and Castleisland in area at at area For water lovers and water adventure sport enthusiasts County Kerry has an has Kerry County enthusiasts sport adventure water and lovers water For Expressway coaches link County Kerry with locations nationwide. -

Deer Park Killarney, County Kerry

PRIME RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT LAND DEER PARK KILLARNEY, COUNTY KERRY For Sale by Private Treaty Sale Highlights • Located in the highly sought after town of Killarney. • The site extends to approximately 3.8 hectares (9.4 acres). • Entire site zoned “New/Proposed Residential Development” in the Draft Killarney Municipal District Local Area Plan. • Within walking distance of Killarney train station, Deer Park Shopping Centre & Killarney town centre. • Potential to develop a high quality residential scheme (SPP). The opportunity Description Joint agents Savills and Tom Spillane & Company are The subject property comprises an undeveloped delighted to offer for sale this superb residential greenfield site extending to approximately 3.8 hectares development opportunity in one of Kerry's most desirable (9.4 acres) in total. The site is irregular in configuration locations. The property comprises a c.9.4 acre greenfield and is generally flat throughout. The site is bound by a site in a superb location within walking distance of Killarney mature residential estate type development to the west, train station, Deer Park Shopping Centre and Killarney Town Deer Park Shopping Centre to east and activity open Centre. The opportunity now exists to acquire this prime space to the north with mature trees and hedgerows residential development site in a proven sales location that acting as natural boundaries and providing a private has long been regarded as one of Kerry’s most sought after and secluded setting. residential addresses. Location Killarney is part of the scenic Ring of Kerry route and is a very TOWN CENTRE popular tourist destination, listed as the 8th best global tourist DEER PARK SHOPPING CENTRE destination by Trivago in 2016. -

Kenmare – Escape to Living

Kenmare – Escape to Living Places to see – All within a short drive of Kenmare 1 Kenmare – Heritage Town 11 Skellig Islands – Star Wars To Co Clare & The Burren 2 Bonane Heritage Park 12 Skellig Ring Drive To Limerick 3 Allihies Copper Mine Museum 13 Tetrapod Footprints 4 Dursey Island Cable Car 14 Kerry Bog Village 18 N69 5 Bantry House and Gardens 15 Birthplace of Tom Crean Tarbert 6 Mizen Head Visitor Centre 16 Fungi Dolphin Ballybunion 7 Skibbereen Famine Centre 17 Blasket Island Centre 19 8 Killarney National Park 18 Tralee Wetlands Centre Newcastle 9 Sneem Sculpture Garden 19 Surfing Centre West Listowel 10 Derrynane National Park 20 Kerry Literary Centre 20 N21 Ballyheigue R551 Abbeyfeale ® N69 18 N21 Brandon Fenit 9 Castlegregory TRALEE 18 Dingle Camp Castleisland 18 N70 R560 Peninsula Conor Pass N86 Castlemaine N23 Kerry Airport DINGLE Annascaul R561 Farranfore 17 15 Inch Milltown N22 R559 18 R563 16 Aghadoe Slea Head Killorglin N72 To Mallow Blasket Islands N70 KILLARNEY 18 N72 Beaufort 14 Glenbeigh N22 Kells Glenflesk Glencar Ladies View Ring of 8 N71 N70 Kerry Ballagh R569 Ballyvourney Beama Moll’s Gap N22 13 Cahersiveen Pass Valentia Island R565 CORK 18 KENMARE Kilgarvan Portmagee N70 R568 18 1 Gougan Barra R584 9 18 N70 KEY 12 R566 Waterville Sneem R571 N71 18 Golf Ballinskelligs 18 Bonane R584 Tuosist 2 Cycling Route Castlecove Beara Water Sports Caherdaniel Glengarriff 10 9 Kealkill Kerry Way Walking Route 11 Lauragh Healy Pass Skellig Islands Beara Way Walking Route Ardgroom R572 Ballylickey Dunmanway N71 Adrigole Wild -

Mykidstime Family Guide to County Kerry Top Ten Things to Do in Kerry

Mykidstime Family Guide to County Kerry Welcome to the Mykidstime Guide to County Kerry. We have put together some suggestions to make your family’s visit to County Kerry as enjoyable as possible. As parents ourselves, we are delighted to share with you some of the family friendly spots round our beautiful County Kerry! The Mykidstime Team Top Ten Things to do in Kerry 1. Visit the Muckross Traditional Farms in Killarney where the whole family can take a step back in time to rural Ireland. Meet and chat with the farmers and their wives as they go about their daily work in the houses, on the land, and with the animals. 2. Take a walk in Killarney National Park and admire the beautiful views of its many lakes and you might even see a glimpse of a famous red deer in the woods. 3. Take a boat trip out to the magnificent Skellig Islands in South West Kerry. 4. Take a ride on the Europe’s most westerly railway line: Tralee–Dingle Steam Railway. 5. Fly a kite or dig in the sand on one of many Kerry’s many blue flag beaches such as Inch, Banna, Ballyheigue, Derrynane or Ballybunion. 6. Drive along the Ring of Kerry which will provide an insight into the heritage of Ireland - see the Iron Age Forts & Ogham Stones, Old Monasteries and a landscape carved out of rock by the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago. The Trail takes you through many diverse and interesting villages and towns with an abundance of pubs and restaurants along with a variety of accommodation to suit just about everyone. -

14/11/2019 11:44 the Kerry Archaeological & Historical Society

KAHS_Cover_2020.indd 1 14/11/2019 11:44 THE KERRY ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HISTORICAL SOCIETY EDITORIAL COMMENT CALL FOR PARTICIPATION: THE YOUNG It is scarcely possible to believe, that this magazine is the 30th in We always try to include articles the series. Back then the editor of our journal the late Fr Kieran pertaining to significant anniversaries, O’Shea, was having difficulties procuring articles. Therefore, the be they at county or national level. KERRY ARCHAEOLOGISTS’ CLUB Journal was not being published on a regular basis. A discussion This year, we commemorate the 50th Are you 15 years of age or older and interested in History, Archaeology, Museums and Heritage? In partnership with Kerry occurred at a council meeting as to how best we might keep in anniversary of the filming of Ryan’s County Museum, Kerry Archaeological & Historical Society is in the process of establishing a Young Kerry Archaeologists’ contact with our membership and the suggestion was made that a Daughter on the Dingle Peninsula. An Club, in which members’ children can participate. If you would like to get actively involved in programming and organizing “newsletter” might be a good idea. Hence, what has now become event, which catapulted the beauty of events for your peers, please send an email to our Education Officer: [email protected]. a highly regarded, stand-alone publication was born. Subsequent, the Peninsula onto the world stage, to this council meeting, the original sub-committee had its first resulting in the thriving tourism meeting. It was chaired by Gerry O’Leary and comprised of the industry, which now flourishes there. -

Church Island Graveyard, Lough Currane, Waterville, Co

Archaeological Survey, Church Island Graveyard, Lough Currane, Waterville, Co. Kerry. September 2012 Client: The Heritage Offi ce, Kerry County Council, County Buildings, Ratass, Tralee, Co. Kerry. RMP No.: KE098-039 Archaeological Surveyor: Daire Dunne Contact details: 3 Lios na Lohart, Ballyvelly, Tralee, Written by: Laurence Dunne Co. Kerry. Tel.: 0667120706 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.ldarch.ie Archaeological Survey, Church Island Graveyard, Lough Currane, Waterville, Co. Kerry. Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................2 Site Location ..........................................................................................................................................3 General ....................................................................................................................................................3 Approach ................................................................................................................................................4 Entrance and boundaries ...................................................................................................................4 Services & Signage ...............................................................................................................................4 Pathways .................................................................................................................................................5 -

Escape to Living

Kenmare – Escape to Living Places to see – All within a short drive of Kenmare 1 Kenmare – Heritage Town 11 Skellig Islands – Star Wars To Co Clare & The Burren 2 Bonane Heritage Park 12 Skellig Ring Drive To Limerick 3 Allihies Copper Mine Museum 13 Tetrapod Footprints 4 Dursey Island Cable Car 14 Kerry Bog Village 18 N69 5 Bantry House and Gardens 15 Birthplace of Tom Crean Tarbert 6 Mizen Head Visitor Centre 16 Fungi Dolphin Ballybunion 7 Skibbereen Famine Centre 17 Blasket Island Centre 19 8 Killarney National Park 18 Tralee Wetlands Centre Newcastle 9 Sneem Sculpture Garden 19 Surfing Centre West Listowel 10 Derrynane National Park 20 Kerry Literary Centre 20 N21 Ballyheigue R551 Abbeyfeale ® N69 18 N21 Brandon Fenit 9 Castlegregory TRALEE 18 Dingle Camp Castleisland 18 N70 R560 Peninsula Conor Pass N86 Castlemaine N23 Kerry Airport DINGLE Annascaul R561 Farranfore 17 15 Inch Milltown N22 R559 18 R563 16 Aghadoe Slea Head Killorglin N72 To Mallow Blasket Islands N70 KILLARNEY 18 N72 Beaufort 14 Glenbeigh N22 Kells Glenflesk Glencar Ladies View Ring of 8 N71 N70 Kerry Ballagh R569 Ballyvourney Beama Moll’s Gap N22 13 Cahersiveen Pass Valentia Island R565 CORK 18 KENMARE Kilgarvan Portmagee N70 R568 18 1 Gougan Barra R584 9 18 N70 KEY 12 R566 Waterville Sneem R571 N71 18 Golf Ballinskelligs 18 Bonane R584 Tuosist 2 Cycling Route Castlecove Beara Water Sports Caherdaniel Glengarriff 10 9 Kealkill Kerry Way Walking Route 11 Lauragh Healy Pass Skellig Islands Beara Way Walking Route Ardgroom R572 Ballylickey Dunmanway N71 Adrigole Wild -

Corners of Southern Ireland: Ennis, Killarney, Kinsale, and Kilkenny

6 Days/5 Nights Departs Selected Dates Apr.-Sep. from Dublin Corners of Southern Ireland: Ennis, Killarney, Kinsale, and Kilkenny Ireland is renowned for its warm welcome and Irish craic. This tour is an ideal introduction to a diverse land dominated by wild, breath-taking vistas and vivacious people. Gaze in awe at the sheer scale of the Cliffs of Moher from the sea below, travel through County Clare, home to exceptional scenic delights and charming villages. Try Irish cuisine, sample a variety of whiskies and meet local characters in timeless pubs. ACCOMMODATIONS •1 Night Ennis •1 Night Kinsale •1 Night Kilkenny •2 Nights Killarney INCLUSIONS •All Ground Transfers via •1 Hour Cliffs of Moher •Jameson Midleton 16-Passenger Minicoach Cruise Distillery Visit & Whiskey •Touring + Professional •Entrance to The Skellig Tasting Guide Experience •Kilkenny Castle Visit •Guided Tour of Irish •Kinsale Heritage Walk •3 Dinners National Stud •Daily Breakfast DUBLIN–KILDARE–ENNIS: After meeting our tour leader and fellow travellers we leave Dublin and travel to County Kildare, the beating heart of Ireland’s thoroughbred industry. Here we enjoy a private guided tour of the Irish National Stud, the only stud farm in Ireland open to the public. During the tour we will see some of Ireland’s finest thoroughbred horses, visit the horse museum and explore the world famous Japanese Gardens, renowned as one of the finest examples in Europe. We continue to Portumna Castle, a semi- fortified house built around 1618, with a beautifully restored 17th century potager kitchen garden. Our final destination today is The Old Ground Hotel in Ennis. -

For Inspection Purposes Only. Consent of Copyright Owner Required for Any Other Use

For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. EPA Export 26-07-2013:23:59:44 Archaeological Assessment, Dredging and Dumping Development, Tarbert Power Plant, River Shannon Estuary, Co. Kerry. Document prepared by: Boland Archaeological Services Ltd. , Arden Road, Tullamore, Co.Offaly, Tel. and Fax: 0506-41488 Mobile 087 2653468 Data Acquisition: Mr. Donal Boland Data Processing and Interpretation: Mr. Donal Boland Historical Data: Mr. Rory McNeary Geophysical survey conducted under The National Monuments Act 1930-1994: Licence No. 02R181 020120 Client: Electricity Supply Board BAS Ltd. Report Number BAS 01-01-03 For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Boland Archaeoloaical Services Ltd.: BAS 01-01-03 Page-2 EPA Export 26-07-2013:23:59:44 Archaeological Assessment, Dredging and Dumping Development, Tarbert Power Plant, River Shannon Estuary, Co. Kerry. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction 1.2 The Site 1.3 The Development 1.4 Historical and Archaeological Background 1.5 Sites and Monuments Record of Tarbert 1.6 Shipwrecks Listed for the Area of Tarbert 2. THE SITE SURVEY 2.1 The Site Survey Design 2.2 The Foreshore Surveys 2.3 Dredge and Dump Site Surveys 3. IMPACTS CONCLUSIONS MITIGATION 3.1 Impacts 3.2 Conclusions 3.3 Mitigation 4. BIBLIOGRAPHY For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. 4.1 Geophysical References 4.2 Historical Sources Boland Archaeoloaical Services Ltd.: BAS 01 -01 -03 Page-3 EPA Export 26-07-2013:23:59:44 Archaeological Assessment, Dredging and Dumping Development, Tarbert Power Plant, River Shannon Estuary, Co. -

The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers

THE LIST of CHURCH OF IRELAND PARISH REGISTERS A Colour-coded Resource Accounting For What Survives; Where It Is; & With Additional Information of Copies, Transcripts and Online Indexes SEPTEMBER 2021 The List of Parish Registers The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers was originally compiled in-house for the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), now the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), by Miss Margaret Griffith (1911-2001) Deputy Keeper of the PROI during the 1950s. Griffith’s original list (which was titled the Table of Parochial Records and Copies) was based on inventories returned by the parochial officers about the year 1875/6, and thereafter corrected in the light of subsequent events - most particularly the tragic destruction of the PROI in 1922 when over 500 collections were destroyed. A table showing the position before 1922 had been published in July 1891 as an appendix to the 23rd Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Ireland. In the light of the 1922 fire, the list changed dramatically – the large numbers of collections underlined indicated that they had been destroyed by fire in 1922. The List has been updated regularly since 1984, when PROI agreed that the RCB Library should be the place of deposit for Church of Ireland registers. Under the tenure of Dr Raymond Refaussé, the Church’s first professional archivist, the work of gathering in registers and other local records from local custody was carried out in earnest and today the RCB Library’s parish collections number 1,114. The Library is also responsible for the care of registers that remain in local custody, although until they are transferred it is difficult to ascertain exactly what dates are covered.