The Ground Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Medicine in Context'

FOUND IN TRANSLATION ‘Medicine in context’ An epistemological trajectory Hansjörg Dilger and Bernhard Hadolt Keywords theory, epistemology, context, globalization, transnationalism What is the role of medical anthropology in a globalized world that is becoming increasingly complex and interconnected? Where does the defining domain of our subdiscipline begin and end with regard to our ‘classical’ objects of study such as ‘medicine’, ‘health system(s)’, and ‘the body’, and how is it possible to decide what constitutes the anthropologically relevant ‘context’ of these (empirically defined) research fields? How can we open the horizons of the subdisciplines of social and cultural anthropology to medical anthropology, and to what extent do the demarcations between medical anthropology and other areas of the discipline that deal with politics, economics, law, science, religion, and urban environments even make sense? Where do the inter- and transdisciplinary junctions emerge that can provide for general reflections about the themes, challenges, and positions of medical anthropology in an interconnected world? These were the questions occupying our minds as we prepared for the conference ‘Medicine in Context: Illness and Health in an Interconnected World’, organized in 2007 by the Work Group Medical Anthropology within the German Anthropological Association on the occasion of its tenth anniversary. The following text forms the introduction to the anthology of the same name (Dilger and Hadolt 2010), which was published under our oversight as the Medicine Anthropology Theory 2, no. 3: 128–153; https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.2.3.333 © Hansjörg Dilger and Bernhard Hadolt. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. -

Interview with Maurice Bloch

INTERVIEW WITH MAURICE BLOCH Professor Maurice Bloch visited Finland in Timo Kallinen (TK): You have contributed to March 2014 as the keynote speaker of the different fields of anthropology, but the study of interdisciplinary symposium ‘Ritual Intimacy— ritual seems to have been there ever since the Ritual Publicity’ organized by the Collegium for early stages of your career. How did you become Advanced Studies at the University of Helsinki. originally interested in ritual? As one of the most influential thinkers in contemporary anthropology Professor Bloch Maurice Bloch (MB): My interest in ritual has made significant contributions to various has been a key concern for a very long part research fields such as kinship studies and of my career but this has been because I have economic anthropology, but he is probably been able to link it to other central aspects of best known for his groundbreaking work on human life. My main interest has been with the ritual and religion. In his writings Professor apparent authority of ritual and the nature of Bloch often draws on his ethnography from this apparent authority. I outlined my position Madagascar, where he has carried out fieldwork in one of my earliest papers (Bloch 1974). over a period of several decades. Lately he I want to explore how ritual is linked to ideology, has also become renowned for developing an that is, to systems which seem to justify and approach that seeks to find a common ground maintain social hierarchy and social continuity between sociocultural anthropology and (Bloch 1986). The connection of authority cognitive science. -

Truth and Sight: Generalizing Without Universalizing

Maurice Bloch Truth and sight: generalizing without universalizing Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Bloch, Maurice (2008) Truth and sight: generalizing without universalizing. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 14 (s1). s22-s32. ISSN 1467-9655 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.00490.x © 2008 Royal Anthropological Institute This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk//27112/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2010 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Truth and Sight: generalising without universalising Maurice Bloch Abstract: This article examines the link between truth and sight, and the implications of this link for our understandings of the concept of evidence. I propose to give an example of precisely how we might attempt to generalise about a phenomena such as the recurrence of the association between truth and sight without ignoring important anti-universalist points. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fv121wm Author Stroud, Martha Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair Professor Laura Nader Professor Sharon Kaufman Professor Jeffrey A. Hadler Spring 2015 “Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia” © 2015 Martha Stroud 1 Abstract Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair In Indonesia, during six months in 1965-1966, between half a million and a million people were killed during a purge of suspected Communist Party members after a purported failed coup d’état blamed on the Communist Party. Hundreds of thousands of Indonesians were imprisoned without trial, many for more than a decade. The regime that orchestrated the mass killings and detentions remained in power for over 30 years, suppressing public discussion of these events. It was not until 1998 that Indonesians were finally “free” to discuss this tragic chapter of Indonesian history. In this dissertation, I investigate how Indonesians perceive and describe the relationship between the past and the present when it comes to the events of 1965-1966 and their aftermath. -

Culture, Health and Illness (Introduction to Medical Anthropology)

Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia Anthropology 227.001 Winter 2007 Culture, Health and Illness (Introduction to Medical Anthropology) Instructor Teaching Assistant Dr. Vinay R. Kamat Stephen Robbins Class: Mon, Wed, Fri 10:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. Office: ANSO 0305 Lasserre, 6333 Memorial Road, Room 104 Office hours: Mon, Wed, 11:00-12:00 Office: ANSO 2319; Office phone 604-822-4802 Email: [email protected] Office hours: Mon, Wed, 11:30 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Email: [email protected] Course Description This is an introductory course in medical anthropology which includes the study of health, illness and healing from a cross-cultural perspective. The course examines aspects of health and illness from a biocultural perspective. In reading ethnographic materials from Western and non-Western settings, we will explore how medical anthropologists creatively use different theoretical and methodological approaches to understand and highlight how health, illness and healing practices are culturally constructed and mediated. The case studies and other required readings will help us learn to appreciate the contribution of medical anthropology to the study of international public health problems including specific life-threatening diseases such as HIV/ AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. Topics covered by this course include cultural interpretations of sickness and healing, medical systems as social systems, medical pluralism, belief and ethnomedical systems, medical decision making, social relations of therapy management, cultural construction of efficacy and “side-effects,” pharmaceuticalization of health, explanatory models, cultural competence, narrative representation of illness, the body and debate surrounding female genital mutilation/ cutting, the political economy of HIV/AIDS in Africa, structural violence and social suffering, the New Genetics and social stigma. -

Desire, Discord, and Death : Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Myth / by Neal Walls

DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH ASOR Books Volume 8 Victor Matthews, editor Billie Jean Collins ASOR Director of Publications DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH by Neal Walls American Schools of Oriental Research • Boston, MA DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH Copyright © 2001 American Schools of Oriental Research Cover art: Cylinder seal from Susa inscribed with the name of worshiper of Nergal. Photo courtesy of the Louvre Museum. Cover design by Monica McLeod. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Walls, Neal H., 1962- Desire, discord, and death : approaches to ancient Near Eastern myth / by Neal Walls. p. cm. -- (ASOR books ; v. 8) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-89757-056-1 -- ISBN 0-89757-055-3 (pbk.) 1. Mythology--Middle East. 2. Middle East--Literatures--History and crticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Desire in literature. I. Title. II. Series. BL1060 .W34 2001 291.1'3'09394--dc21 2001003236 Contents ABBREVIATIONS vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii INTRODUCTION Hidden Riches in Secret Places 1 METHODS AND APPROACHES 3 CHAPTER ONE The Allure of Gilgamesh: The Construction of Desire in the Gilgamesh Epic INTRODUCTION 9 The Construction of Desire: Queering Gilgamesh 11 THE EROTIC GILGAMESH 17 The Prostitute and the Primal Man: Inciting Desire 18 The Gaze of Ishtar: Denying Desire 34 Heroic Love: Requiting Desire 50 The Death of Desire 68 CONCLUSION 76 CHAPTER TWO On the Couch with Horus and Seth: A Freudian -

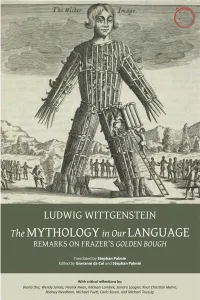

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

Erica Caple James

Erica Caple James MIT Anthropology Program 77 Massachusetts Avenue Room E53-335G Cambridge, MA 02139-4307 (617) 253-7321 [email protected] EDUCATION Harvard University, Ph.D. in Social Anthropology 2003 Harvard University, A.M. in Social Anthropology 1998 Harvard Divinity School, Masters of Theological Studies (M.T.S.) 1995 Princeton University, A.B. in Anthropology 1992 DISSERTATION “The Violence of Misery: ‘Insecurity’ in Haiti in the ‘Democratic’ Era” Advisor: Dr. Arthur Kleinman FELLOWSHIPS AND HONORS Abdul Latif Jameel World Water and Food Security Lab Grant 2015-2017 Todman Family Fund, for launch of Global Health and Medical Humanities Initiative 2014 Alumni Class Funds 2014 Tenure, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2013 Gordon K. and Sybille Lewis (Book) Award, Caribbean Studies Association 2013 School for Advanced Research on the Human Experience, Advanced Seminar 2013 James A. and Ruth Levitan Prize in the Humanities, MIT 2012 Gregory Bateson Book Prize, Society for Cultural Anthropology, Honorable Mention 2011 MIT Old Dominion Fellowship 2011 Class of 1947 Career Development Professorship 2010 Rita E. Hauser Fellow, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study 2010-2011 MIT School of the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences Research Fund 2009 NIH National Loan Repayment Program Funding for Health Disparities Research 2007-2009 Career Enhancement Fellowship, Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation, 2007 Honorable Mention Mellon Foundation Support for the Study of Science, Technology, and Medicine 2006 School of the Humanities, -

INTRODUCTION a Concept Note

INTRODUCTION A Concept Note Clara Han and Veena Das Dōgen, a thirteenth-century Buddhist scholar from Japan, provocatively reversed the commonsense notion of life and death, which takes birth as the inception of a linear stretch of time over which a particular life is lived and death as the moment of cessation of that time. Instead, he thought that within Buddhist practice and hence within each moment, life and death can be seen as working together. What if we took such ways of conceptualizing the relation between life and death as present not only in exotic practices but also in concepts generated from the experiences of everyday life and its perils? Then we could become attentive to the multiple forms in which human societies generate understanding of life that comes from their varied experiences of how living and dying have been transformed in our contemporary conditions. This book is conceived as a response to the idea that our concepts are honed from the everyday experiences to which the people we study struggle to give expression, and to the idea that we ourselves become apprentices to death as we survey the altered landscape on which life and death become conjoined in our contemporary world. Our intention in this introductory chapter is not to summarize the chapters that follow: the section introductions show how the particular chapters in each section take forward the ways in which life and death are folded together in the lives of individuals and communities. Here we want to reflect on how anthropo- logical conceptions of life have absorbed the discussion of these issues from philosophy and from the history of medicine even as the anthropological attention to the concrete- ness of lives and deaths has put pressure on the abstract formulations of these other disciplines. -

Current Anthropology October 2015 Volume 56 Supplement 11 Pages S1–S180

Forthcoming Current Anthropology Wenner-Gren Symposium Current Anthropology Supplementary Issues (in order of appearance) VOLUME 56 SUPPLEMENT 11 OCTOBER 2015 The Life and Death of the Secret. Lenore Manderson, Mark Davis, and Current Chip Colwell, eds. Reintegrating Anthropology: From Inside Out. Agustín Fuentes and Polly Wiessner, eds. Anthropology Previously Published Supplementary Issues Working Memory: Beyond Language and Symbolism. Thomas Wynn and Frederick L. Coolidge, eds. THE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas. Setha M. Low and October 2015 Sally Engle Merry, eds. POLITICS OF THE URBAN POOR: AESTHETICS, Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form. Damani Partridge, Marina Welker, and Rebecca Hardin, eds. ETHICS, VOLATILITY, PRECARITY The Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. T. Douglas Price and GUEST EDITORS: VEENA DAS AND SHALINI RANDERIA Ofer Bar-Yosef, eds. The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations: World Histories, Politics of the Urban Poor: Aesthetics, Ethics, Volatility, Precarity National Styles, and International Networks. Susan Lindee and 56 Volume The Urban Poor and Their Ambivalent Exceptionalities: Notes from Jakarta Ricardo Ventura Santos, eds. The Politics of Not Studying the Poorest of the Poor in Urban South Africa Human Biology and the Origins of Homo. Susan Antón and Leslie C. Plebeians of the Arab Spring Aiello, eds. Political Leadership and the Urban Poor: Local Histories Potentiality and Humanness: Revisiting the Anthropological Object in The Need for Patience: The Politics of Housing Emergency in Buenos Aires Contemporary Biomedicine. Klaus Hoeyer and Karen-Sue Taussig, eds. The Politics of the Urban Poor in Postwar Colombo Supplement 11 Alternative Pathways to Complexity: Evolutionary Trajectories in the Middle Sectarianism and the Ambiguities of Welfare in Lebanon Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age. -

Three Approaches to the Study of Health, Disease and Illness; the Strengths and Weaknesses of Each, with Special Reference to Refugee Populations

Anne Sigfrid Grønseth Three approaches to the study of health, disease and illness; the strengths and weaknesses of each, with special reference to refugee populations NAKMIs skriftserie om minoriteter og helse 2/2009 Redaktør Karin Harsløf Hjelde Anne Sigfrid Grønseth Three approaches to the study of health, disease and illness; the strengths and weaknesses of each, with special reference to refugee populations NAKMIs skriftserie om minoriteter og helse 2/2009 Redaktør Karin Harsløf Hjelde © NAKMI – Nasjonal kompetanseenhet for minoritetshelse 2009 NAKMIs skriftserie for minoriteter og helse Serieredaktør: Karin Harsløf Hjelde ISSN 1503-1659 ISBN 978-82-92564-06-6 Design og produksjon: 07 Gruppen AS Alle henvendelser om rapporten kan rettes til: NAKMI Oslo Universitetssykehus, HF, avd. Ullevål Bygg 37 0407 Oslo Tlf.: 23 01 60 60 Faks: 23 01 60 61 [email protected] www.nakmi.no Three approaches to the study of health, disease and illness; the strengths and weaknesses of each, with special reference to refugee populations. Thesis Defence Lecture, Dr. Polit, NTNU 15 December 2006 Anne Sigfrid Grønseth Introduction In this lecture I start by establishing a thematic and conceptual context in which to under- stand health, illness and disease, as well as refugee populations. Then I turn to three approaches that highlight distinct and interrelated aspects in the exploration and under- standing of illness and health. Each of these approaches will be evaluated in terms of its strengths and weaknesses with special reference to refugee populations. Introducing the different perspectives, I provide a general description supported by references to well known studies. Further, I have selected one recent case study for each, on which I elaborate more extensively. -

Gender and Sexuality

PERSPECTIVES: AN OPEN INTRODUCTION TO CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY SECOND EDITION Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González 2020 American Anthropological Association 2300 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1301 Arlington, VA 22201 ISBN Print: 978-1-931303-67-5 ISBN Digital: 978-1-931303-66-8 http://perspectives.americananthro.org/ This book is a project of the Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges (SACC) http://sacc.americananthro.org/ and our parent organization, the American Anthropological Association (AAA). Please refer to the website for a complete table of contents and more information about the book. Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition by Nina Brown, Thomas McIlwraith, Laura Tubelle de González is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Under this CC BY-NC 4.0 copyright license you are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material Under the following terms: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. 1010 GENDER AND SEXUALITY Carol C. Mukhopadhyay, San Jose State University [email protected] http://www.sjsu.edu/people/carol.mukhopadhyay Tami Blumenfield, Yunnan University [email protected] with Susan Harper, Texas Woman’s University, [email protected], and Abby Gondek, [email protected] Learning Objectives • Identify ways in which culture shapes sex/gender and sexuality.