Endosulfan Fact Sheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is the Difference Between Pesticides, Insecticides and Herbicides? Pesticide Effects on Food Production

What is the Difference Between Pesticides, Insecticides and Herbicides? Pesticides are chemicals that may be used to kill fungus, bacteria, insects, plant diseases, snails, slugs, or weeds among others. These chemicals can work by ingestion or by touch and death may occur immediately or over a long period of time. Insecticides are a type of pesticide that is used to specifically target and kill insects. Some insecticides include snail bait, ant killer, and wasp killer. Herbicides are used to kill undesirable plants or “weeds”. Some herbicides will kill all the plants they touch, while others are designed to target one species. Pesticide Effects on Food Production As the human population continues to grow, more and more crops are needed to meet this growing demand. This has increased the use of pesticides to increase crop yield per acre. For example, many farmers will plant a field with Soybeans and apply two doses of Roundup throughout the growing year to remove all other plants and prepare the field for next year’s crop. The Roundup is applied twice through the growing season to kill everything except the soybeans, which are modified to be pesticide resistant. After the soybeans are harvested, there is little vegetative cover on the field creating potential erosion issues for the reason that another crop can easily be planted. With this method, hundreds of gallons of chemicals are introduced into the environment every year. All these chemicals affect wildlife, insects, water quality and air quality. One greatly affected “good” insect are bees. Bees play a significant role in the pollination of the foods that we eat. -

Factors Influencing Pesticide Resistance in Psylla Pyricola Foerster and Susceptibility Inits Mirid

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF: Hugo E. van de Baan for the degree ofDoctor of Philosopbv in Entomology presented on September 29, 181. Title: Factors Influencing Pesticide Resistance in Psylla pyricola Foerster and Susceptibility inits Mirid Predator, Deraeocoris brevis Knight. Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Factors influencing pesticide susceptibility and resistance were studied in Psylla pyricola Foerster, and its mirid predator, Deraeocoris brevis Knight in the Rogue River Valley, Oregon. Factors studied were at the biochemical, life history, and population ecology levels. Studies on detoxification enzymes showed that glutathione S-transferase and cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase activities were ca. 1.6-fold higherin susceptible R. brevis than in susceptible pear psylla, however, esterase activity was ca. 5-fold lower. Esterase activity was ca. 18-fold higher in resistant pear psylla than in susceptible D. brevis, however, glutathione S-transferase and cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase activities were similar. Esterases seem to be a major factor conferring insecticideresistance in P. Pvricola. Although the detoxification capacities of P. rivricola and D. brevis were quite similar, pear psylla has developed resistance to many insecticides in the Rogue River Valley, whereas D. brevis has remained susceptible. Biochemical factors may be important in determining the potential of resistance development, however, they are less important in determining the rate at which resistance develops. Computer simulation studies showed that life history and ecological factors are probably of greater importancein determining the rate at which resistance develops in P. pvricola and D. brevis. High fecundity and low immigration of susceptible individuals into selected populations appear to be major factors contributing to rapid resistance development in pear psylla compared with D. -

Replacement Therapy, Not Recreational Tonic Testosterone, Widely Used As a Lifestyle Drug, Is a Medicine and Should Be Kept As Such

correspondence Replacement therapy, not recreational tonic Testosterone, widely used as a lifestyle drug, is a medicine and should be kept as such. Sir — We read with great interest the News male tonics and remedies — most harmless, your Feature that there is a need for large- Feature “A dangerous elixir?” (Nature 431, but some as drastic as grafting goat testicles scale, long-term clinical trials to address 500–501; 2004) reporting the zeal with onto humans. Unfortunately, a certain several issues associated with testosterone which testosterone is being requested by amount of quackery is now perceived to be use. For example, testosterone therapy may men who apparently view the hormone as associated with testosterone therapy, and the be beneficial against osteoporosis, heart a ‘natural’ alternative to the drug Viagra. increased prescription of the hormone in disease and Alzheimer’s disease, but the Like Viagra, testosterone replacement recent years does little to dispel this notion. dangers remain obscure. therapy — with emphasis on the word Nonetheless, as your Feature highlights, Until we know more, both prescribing ‘replacement’ — is a solution to a very real hypogonadism is a very real clinical clinicians and the male population need to clinical problem. There is a distinction condition. It is characterized by abnormally be aware that testosterone, like any other between patients whose testosterone has low serum levels of testosterone, in medication, should only be administered declined to abnormally low levels, and conjunction with symptoms such as to patients for whom such therapy is individuals seeking testosterone as a pick- mood disturbance, depression, sexual clinically indicated. me-up. -

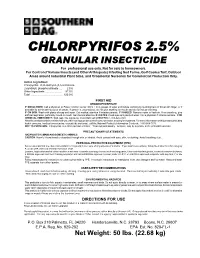

CHLORPYRIFOS 2.5% GRANULAR INSECTICIDE for Professional Use Only

CHLORPYRIFOS 2.5% GRANULAR INSECTICIDE For professional use only. Not for sale to homeowners. For Control of Various Insects (and Other Arthropods) Infesting Sod Farms, Golf Course Turf, Outdoor Areas around Industrial Plant Sites, and Ornamental Nurseries for Commercial Production Only. Active Ingredient: Chlorpyrifos: O,O-diethyl-0-(3,5,6-trichloro- 2-pyridinyl) phosphorothioate .... 2.5% Other Ingredients ....................... 97.5% Total ............................................ 100.0% FIRST AID ORGANOPHOSPHATE IF SWALLOWED: Call a physician or Poison Control Center. Drink 1 or 2 glasses of water and induce vomiting by touching back of throat with finger, or if available by administering syrup of ipecac. If person is unconscious, do not give anything by mouth and do not induce vomiting. IF ON SKIN: Wash with plenty of soap and water. Get medical attention if irritation persists. IF INHALED: Remove victim to fresh air. If not breathing, give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth. Get medical attention. IF IN EYES: Flush eyes with plenty of water. Call a physician if irritation persists. FOR CHEMICAL EMERGENCY: Spill, leak, fire, exposure, or accident call CHEMTREC 1-800-424-9300. Have the product container or label with you when calling a poison control center or doctor, or going for treatment. For more information on this product (including health concerns, medical emergencies, or pesticide incidents), call the National Pesticide Information Center at: 1-800-858-7378. NOT TO PHYSICIAN: Chlorpyrifos is a cholinesterase inhibitor. Treat symptomatically. Atropine, only by injection, is the preferable antidote. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS HAZARDS TO HUMANS AND DOMESTIC ANIMALS CAUTION: Harmful if swallowed or absorbed through skin or inhaled. -

DDT and Its Derivatives Have Remained in the Environment

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A Novel Action of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals on Wildlife; DDT and Its Derivatives Have Remained in the Environment Ayami Matsushima Laboratory of Structure-Function Biochemistry, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Kyushu University, Fukuoka 819-0395, Japan; [email protected]; Tel.: +81-92-802-4159 Received: 20 March 2018; Accepted: 2 May 2018; Published: 5 May 2018 Abstract: Huge numbers of chemicals are released uncontrolled into the environment and some of these chemicals induce unwanted biological effects, both on wildlife and humans. One class of these chemicals are endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which are released even though EDCs can affect not only the functions of steroid hormones but also of various signaling molecules, including any ligand-mediated signal transduction pathways. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), a pesticide that is already banned, is one of the best-publicized EDCs and its metabolites have been considered to cause adverse effects on wildlife, even though the exact molecular mechanisms of the abnormalities it causes still remain obscure. Recently, an industrial raw material, bisphenol A (BPA), has attracted worldwide attention as an EDC because it induces developmental abnormalities even at low-dose exposures. DDT and BPA derivatives have structural similarities in their chemical features. In this short review, unclear points on the molecular mechanisms of adverse effects of DDT found on alligators are summarized from data in the literature, and recent experimental and molecular research on BPA derivatives is investigated to introduce novel perspectives on BPA derivatives. Especially, a recently developed BPA derivative, bisphenol C (BPC), is structurally similar to a DDT derivative called dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE). -

Pesticides Reduce Symbiotic Efficiency of Nitrogen-Fixing Rhizobia and Host Plants

Pesticides reduce symbiotic efficiency of nitrogen-fixing rhizobia and host plants Jennifer E. Fox*†, Jay Gulledge‡, Erika Engelhaupt§, Matthew E. Burow†¶, and John A. McLachlan†ʈ *Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Oregon, 335 Pacific Hall, Eugene, OR 97403; †Center for Bioenvironmental Research, Environmental Endocrinology Laboratory, Tulane University, 1430 Tulane Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70112-2699; ‡Department of Biology, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292 ; §University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309; and ¶Department of Medicine and Surgery, Hematology and Medical Oncology Section, Tulane University Medical School, 1430 Tulane Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70112-2699 Edited by Christopher B. Field, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Stanford, CA, and approved May 8, 2007 (received for review January 8, 2007) Unprecedented agricultural intensification and increased crop by plants, in rotation with non-N-fixing crops (8, 15). The yield will be necessary to feed the burgeoning world population, effectiveness of this strategy relies on maximizing symbiotic N whose global food demand is projected to double in the next 50 fixation (SNF) and plant yield to resupply organic and inorganic years. Although grain production has doubled in the past four N and nutrients to the soil. The vast majority of biologically fixed decades, largely because of the widespread use of synthetic N is attributable to symbioses between leguminous plants (soy- nitrogenous fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation promoted by the bean, alfalfa, etc.) and species of Rhizobium bacteria; replacing ‘‘Green Revolution,’’ this rate of increased agricultural output is this natural fertilizer source with synthetic N fertilizer would cost unsustainable because of declining crop yields and environmental Ϸ$10 billion annually (16, 17). -

Historical Use of Lead Arsenate and Survey of Soil Residues in Former Apple Orchards in Virginia

HISTORICAL USE OF LEAD ARSENATE AND SURVEY OF SOIL RESIDUES IN FORMER APPLE ORCHARDS IN VIRGINIA by Therese Nowak Schooley Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN LIFE SCIENCES in Entomology Michael J. Weaver, Chair Donald E. Mullins, Co-Chair Matthew J. Eick May 4, 2006 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: arsenic, lead, lead arsenate, orchards, soil residues, historical pesticides HISTORICAL USE OF LEAD ARSENATE AND SURVEY OF SOIL RESIDUES IN FORMER APPLE ORCHARDS IN VIRGINIA Therese Nowak Schooley Abstract Inorganic pesticides including natural chemicals such as arsenic, copper, lead, and sulfur have been used extensively to control pests in agriculture. Lead arsenate (PbHAsO4) was first used in apple orchards in the late 1890’s to combat the codling moth, Cydia pomonella (Linnaeus). The affordable and persistent pesticide was applied in ever increasing amounts for the next half century. The persistence in the environment in addition to the heavy applications during the early 1900’s may have led to many of the current and former orchards in this country being contaminated. In this study, soil samples were taken from several apple orchards across the state, ranging from Southwest to Northern Virginia and were analyzed for arsenic and lead. Based on naturally occurring background levels and standards set by other states, two orchards sampled in this study were found to have very high levels of arsenic and lead in the soil, Snead Farm and Mint Spring Recreational Park. Average arsenic levels at Mint Spring Recreational Park and Snead Farm were found to be 65.2 ppm and 107.6 ppm, respectively. -

Endosulfan and Endocrine Disruption: Human Risk Characterization

ENDOSULFAN AND ENDOCRINE DISRUPTION: HUMAN RISK CHARACTERIZATION Prepared by Laura M. Plunkett, Ph.D., DABT Integrative Biostrategies, LLC Houston, Texas Prepared for Makhteshim-Agan of North America, Inc. Raleigh, North Carolina June 23, 2008 1 I. Overview of Endocrine Disruption as an Endpoint of Concern in Pesticide Risk Assessment The endocrine system is one of the basic systems in mammalian physiology that is involved in variety of body functions including such functions as growth, development, reproduction, and behavior. The activity of the endocrine system involves endocrine glands which are collections of specialized cells in various tissues of the body that synthesize, store and release substances into the bloodstream. These substances are known as hormones. Hormones act as chemical messengers, traveling through the bloodstream to distant organs and tissues where they can bind to receptors located on those tissues and organs and as a result of receptor binding trigger a physiological response. The major endocrine glands include the pituitary gland, the thyroid gland, the pancreas, the adrenal gland, the testes, and the ovary. “Endocrine disruption”1 is a term that has arisen in human health risk assessment and is defined as the action of an external agent, such as a chemical, to interfere with normal activity of circulating hormones. This “interference” would include altering the synthesis, storage, release, or degradation of hormones, as well as actions at hormone receptors such as stimulating receptor activity (receptor agonist activity) or inhibiting receptor activity (receptor antagonist activity). The potential effects of chemicals, including pesticides, as endocrine disruptors have been a focus of recent regulatory actions. -

Imidacloprid Movement Into Fungal Conidia Is Lethal to Mycophagous Beetles

insects Communication Imidacloprid Movement into Fungal Conidia Is Lethal to Mycophagous Beetles 1, 2, , 3 4 Robin A. Choudhury y , Andrew M. Sutherland * y, Matt J. Hengel , Michael P. Parrella and W. Douglas Gubler 5 1 School of Earth, Environmental, and Marine Sciences, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Edinburg, TX 78539, USA; [email protected] 2 University of California Cooperative Extension, Alameda County, Hayward, CA 94544, USA 3 Department of Environmental Toxicology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology and Nematology, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Plant Pathology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to the writing, design and completion of this work. y Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 30 July 2020; Published: 3 August 2020 Simple Summary: Some insects are beneficial to plants because they eat pest insects and disease-causing fungi; integrating the use of these insects into pest management can help to reduce the need for costly pesticide applications. Twenty-spotted ladybeetles eat plant pathogenic fungi, which helps to reduce disease severity for many economically important crops. In this study, we applied a systemic insecticide to the roots of pumpkin plants and monitored to see if it would be detectable in the spores of a plant pathogenic fungus and whether the insecticide-tainted fungal spores would hurt the ladybeetle larvae. We were able to chemically detect the systemic insecticide in the fungal spores up to 21 days after the plants had been treated with the fungus. -

Past Use of Chlordane, Dieldrin, And

The Hazard Evaluation and Emergency Response Office (HEER Office) is part of the Hawai‘i Department of Health (HDOH) Environmental Health Administration, whose mission is to protect human health and the environment. The HEER Office provides leadership, support, and partnership in preventing, planning for, responding to, and enforcing environmental laws relating to releases or threats of releases of hazardous substances. Past Use of Chlordane, Dieldrin, and other Organochlorine Pesticides for Termite Control in Hawai‘i: Safe Management Practices around Treated Foundations or during Building Demolition This fact sheet provides building owners, demolition and construction contractors, developers, realtors, and others with an overview of the potential environmental concerns associated with the past use of organochlorine termiticides (pesticides used to control termites) in Hawai‘i. In addition, this fact sheet discusses methods for reducing exposure to organochlorine termiticides during building demolition or around the foundations of treated buildings and identifies resources for further information. What are organochlorine termiticides? Organochlorine termiticides are a group of pesticides that were used for termite control in and around wooden buildings and homes from the mid-1940s to the late 1980s. These organochlorine pesticides included chlordane, aldrin, dieldrin, heptachlor, and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). They were used primarily by pest control operators in Hawaii’s urban areas, but also by homeowners, the military, the state, and counties to protect buildings against termite damage. In the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned all uses of these organochlorine pesticides except for heptachlor, which can be used today only for control of fire ants in underground power transformers. -

Indoor Dust Poses Significant Endocrine Disruptor Risk

9 October 2008 Indoor dust poses significant endocrine disruptor risk The risks from exposure to outdoor pollution or sources like tobacco smoke are well known, but indoor dust can also pose health risks, especially to young children. New evidence shows that indoor dust is highly contaminated by persistent and endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including some chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) which have been banned since the 1970s. Endocrine disruptors are substances which disrupt the body’s natural hormonal system. Some endocrine- disrupting chemicals can persist for many years. These include PCBs, polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), pyrethroids, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), chlorodanes and phthalates. These chemicals and others are found in indoor dust, which can be eaten or breathed in. Endocrine disrupters may be responsible for declining sperm counts, genital malformations, cancers and impaired neural development and sexual behaviour. Dust collected from vacuum cleaners used in apartments and a community hall was highly contaminated with endocrine disruptors, in particular phthalates and PBDEs. The levels of PCBs were high enough in some cases to be a health concern, illustrating that these chemicals continue to persist in the environment and pose risks. Although the use of some PBDEs is being phased out in some parts of the US and they have been banned in EU Member States since 2004, this trend may apply to PBDEs as well. PBDEs are flame retardants used on soft furnishings, and so as long as items such as mattresses, carpets and sofas treated with the chemical are used then exposure will continue. Because young children spend a lot of time indoors, often at floor level, and put objects in their mouths, they are particularly at risk from pollutants in indoor dust. -

A General-Purpose Garden Pesticide C

West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources Station Bulletins And Design 1-1-1954 A general-purpose garden pesticide C. K. Dorsey M. E. Gallegly Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ wv_agricultural_and_forestry_experiment_station_bulletins Digital Commons Citation Dorsey, C. K. and Gallegly, M. E., "A general-purpose garden pesticide" (1954). West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station Bulletins. 365T. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wv_agricultural_and_forestry_experiment_station_bulletins/630 This Bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources And Design at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station Bulletins by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BULLETIN 365T June 1954 WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION AUTHORS Authors of A General-Purpose Garden Pesti- cide are C. K. DORSEY, Entomologist and Professor of Entomology, and M. E. GAL- LEGLY, Assistant Plant Pathologist and As- sistant Professor of Plant Pathology. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors are indebted to Kemper L. Callahan for assistance in portions of the studies. West Virginia University Agricultural Experiment Station College of Agriculture, Forestry, and Home Economics H. R. Varney, Director MORGANTOWN A General-Purpose Garden Pesticide C. K. DORSEY and M. E. GALLEGLY IN recent years numerous new insecticides and fungicides have been developed and many have been recommended for use in the home garden. These vary considerably in their effectiveness in the control of different pests. For example, rotenone is effective in controlling the Mexican bean beetle and the potato flea beetle, but is ineffective against the potato leafhopper.