University Micrcxilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper East Region

REGIONAL ANALYTICAL REPORT UPPER EAST REGION Ghana Statistical Service June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ghana Statistical Service Prepared by: ZMK Batse Festus Manu John K. Anarfi Edited by: Samuel K. Gaisie Chief Editor: Tom K.B. Kumekpor ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There cannot be any meaningful developmental activity without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, and socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. The Kilimanjaro Programme of Action on Population adopted by African countries in 1984 stressed the need for population to be considered as a key factor in the formulation of development strategies and plans. A population census is the most important source of data on the population in a country. It provides information on the size, composition, growth and distribution of the population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of resources, government services and the allocation of government funds among various regions and districts for education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users with an analytical report on the 2010 PHC at the regional level to facilitate planning and decision-making. This follows the publication of the National Analytical Report in May, 2013 which contained information on the 2010 PHC at the national level with regional comparisons. Conclusions and recommendations from these reports are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based policy formulation, planning, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programs. -

Maternal Nutrition and Lactational Infertility, Edited by J

Maternal Nutrition and Lactational Infertility, edited by J. Dobbing. Nestld Nutrition, Vevey/ Raven Press, New York © 1985. Maternal Nutrition and Lactational Infertility: A Review Prema Ramachandran National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, India 500007 Ample data exist to show that lactation prolongs postpartum amenorrhoea and provides some degree of protection against pregnancy (1,2). There are, however, marked variations in the duration of lactational infertility among women of different countries and women in different communities in the same country (1,2). Investi- gations undertaken during the past two decades have shown that a large proportion of the observed variations are attributable to differences in the duration of lactation and breastfeeding practices among communities (1). An association between ma- ternal nutritional status and duration of lactational amenorrhoea has also been observed in some of the studies (1). Before reviewing the literature, it might be worthwhile to consider whether delay in return of fertility in undernourished women could constitute a beneficial evo- lutionary adaptation. Famine and acute starvation are dramatic short-term events that result in acute undernutrition. There are data showing that such drastic reduc- tion in food intake and consequent acute undernutrition are associated with amen- orrhoea and reduction in fertility in women (3). With improvement in the food supply, rapid improvement in nutritional status and fertility occur. There are reports of a rebound increase in total marital fertility rates after famine (3). Given the complex socio-economic and political milieu in which famines arise it is unlikely that anyone could document, investigate, and segregate the contribution of under- nutrition per se, as well as the psychological factors, to the observed reduction in fertility during famine. -

Spatio-Temporal Analyses of Impacts of Multiple Climatic Hazards in a Savannah Ecosystem of Ghana ⇑ Gerald A.B

Climate Risk Management xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Climate Risk Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/crm Spatio-temporal analyses of impacts of multiple climatic hazards in a savannah ecosystem of Ghana ⇑ Gerald A.B. Yiran PhD Senior Lecturer a, , Lindsay C. Stringer PhD Professor b a Department of Geography and Resource Development, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana b Sustainability Research Institute, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, UK article info abstract Article history: Ghana’s savannah ecosystem has been subjected to a number of climatic hazards of varying Received 25 January 2016 severity. This paper presents a spatial, time-series analysis of the impacts of multiple haz- Revised 20 June 2016 ards on the ecosystem and human livelihoods over the period 1983–2012, using the Upper Accepted 7 September 2016 East Region of Ghana as a case study. Our aim is to understand the nature of hazards (their Available online xxxx frequency, magnitude and duration) and how they cumulatively affect humans. Primary data were collected using questionnaires, focus group discussions, in-depth interviews and personal observations. Secondary data were collected from documents and reports. Calculations of the standard precipitation index (SPI) and crop failure index used rainfall data from 4 weather stations (Manga, Binduri, Vea and Navrongo) and crop yield data of 5 major crops (maize, sorghum, millet, rice and groundnuts) respectively. Temperature and windstorms were analysed from the observed weather data. We found that tempera- tures were consistently high and increasing. From the SPI, drought frequency varied spa- tially from 9 at Binduri to 13 occurrences at Vea; dry spells occurred at least twice every year and floods occurred about 6 times on average, with slight spatial variations, during 1988–2012, a period with consistent data from all stations. -

Bawku West District

BAWKU WEST DISTRICT Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Bawku West district is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

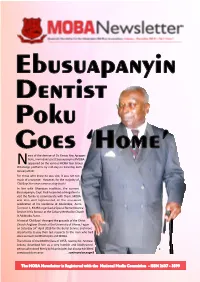

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc. -

Document of the International Fund for Agricultural Development Republic

Document of the International Fund for Agricultural Development Republic of Ghana Upper East Region Land Conservation and Smallholder Rehabilitation Project (LACOSREP) – Phase II Interim Evaluation May 2006 Report No. 1757-GH Photo on cover page: Republic of Ghana Members of a Functional Literacy Group at Katia (Upper East Region) IFAD Photo by: R. Blench, OE Consultant Republic of Ghana Upper East Region Land Conservation and Smallholder Rehabilitation Project (LACOSREP) – Phase II, Loan No. 503-GH Interim Evaluation Table of Contents Currency and Exchange Rates iii Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Map v Agreement at Completion Point vii Executive Summary xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Background of Evaluation 1 B. Approach and Methodology 4 II. MAIN DESIGN FEATURES 4 A. Project Rationale and Strategy 4 B. Project Area and Target Group 5 C. Goals, Objectives and Components 6 D. Major Changes in Policy, Environmental and Institutional Context during 7 Implementation III. SUMMARY OF IMPLEMENTATION RESULTS 9 A. Promotion of Income-Generating Activities 9 B. Dams, Irrigation, Water and Roads 10 C. Agricultural Extension 10 D. Environment 12 IV. PERFORMANCE OF THE PROJECT 12 A. Relevance of Objectives 12 B. Effectiveness 12 C. Efficiency 14 V. RURAL POVERTY IMPACT 16 A. Impact on Physical and Financial Assets 16 B. Impact on Human Assets 18 C. Social Capital and Empowerment 19 D. Impact on Food Security 20 E. Environmental Impact 21 F. Impact on Institutions and Policies 22 G. Impacts on Gender 22 H. Sustainability 23 I. Innovation, Scaling up and Replicability 24 J. Overall Impact Assessment 25 VI. PERFORMANCE OF PARTNERS 25 A. -

Ghana Journal of Development Studies, Volume 7, Number 2 2010

Ghana Journal of Development Studies, Volume 7, Number 2 2010 FISHERIES IN SMALL RESERVOIRS IN NORTHERN GHANA: Incidental Benefit or Important Livelihood Strategy Jennifer Hauck Department for Environmental Politics Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) Leipzig, Germany Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Fisheries in small reservoirs in the Upper East Region are perceived to be an incidental benefit and the potential of this livelihood strategy is neglected. However, in some communities fishing in small reservoirs is part of their livelihood strategies. Several participatory appraisal tools provided entry points for investigations, and supported quantitative surveys, which investigated the number of fishermen and fishmongers, prices of fish, demand for fish and the income derived from fishing and selling fish. For most of those involved in fisheries, the income from these activities is not incidental, but among the three most important livelihood strategies and the income from fishing is lifting about 15% of the economically active male population in the study communities out of absolute poverty. The number of fishmongers and their income are much lower, yet many women rank the income from fishmongering high, and their growing number shows the attractiveness of the activity. Based on these findings this paper recommends to expand government as well as donor efforts to train members of those communities which are currently not able to access fisheries resources to support their livelihoods because of the lack of know-how and fishing gear. KEY DESCRIPTORS: Fisheries, Upper East Region, poverty, malnutrition, income INTRODUCTION In the Upper East Region of Ghana hundreds of small multi-purpose reservoirs were built during the past 60 years (Baijot, Moreau & Bouda, 1997; Braimah, 1990). -

Presentation on the Navrongo Health Research Centre

Navrongo Health Research Centre Ghana Health Service Ministry of Health Abraham Oduro MBChB PhD FGCP Director Location and Contacts UpperUpper EastEast RegionRegion NavrongoNavrongo DSSDSS areaarea Kassena-NankanaKassena-Nankana DistrictDistrict GG HH AA NN AA GhanaGhana 0 25 50 Kilom etre 000 505050 100100100 KilometreKilometreKilometre • Behind War Memorial Hospital, Navrongo • Post Office Box 114, Navrongo , Ghana • Email: [email protected] • Website: www.navrongo-hrc.org Background History • Started in 1998 as Field station for the Ghana Vitamin A Supplementation Trial • Upgraded in 1992 into Health Service Research Centre by Ministry of Health • 1n 2009 became part of R & D Division of the Ghana Health Service Current Affiliations • Currently is One of Three such Centres in Ghana • All under Ghana Health Service, Ministry of Health Vision statement • To be a centre of excellence for the conduct of high quality research and service delivery for national and international health policy development . Mission statement • To undertake health research and service delivery in major national and international health problems with the aim of informing policy for the improvement of health. 1988 - 1992 •Ghana Vitamin A •Navrongo Health Research Supplementation Trial, Centre •(Ghana VAST) • (NHRC-GHS) Prof David Ross Prof Fred Binka Structure and Affiliations Ministry of Health, Ghana Ghana Health Service Council Navrongo Health Research Centre Ghana Health Service (Northern belt) Research & Development Division Kintampo Health Research -

Potential Impact of Large Scale Abstraction on the Quality Of

Land Degradation in the Sudan Savanna of Ghana: A Case Study in the Bawku Area J. K. Senayah1*, S. K. Kufogbe2 and C. D. Dedzoe1 1CSIR-Soil Research Institute, Kwadaso-Kumasi, Ghana 2Department of Geography and Resource Development, University of Ghana, Legon *Corresponding author Abstract The study was carried out in the Bawku area, which is located within the Sudan savanna zone. The study examined the physical environment, human factor and the interactions between them so as to establish the degree and extent of land degradation in the Bawku area. Six rural settlements around Bawku were studied with data on soils collected along transects. Socio-economic information was collected by interviewing key informants and through the administration of questionnaires. Land degradation in the area is the result of interaction between the physical and human environments. Physical environmental characteristics influencing land degradation include soil texture, topography and rainfall. The soils in the study area are developed over granite and Birrimian phyllite. In the granitic areas soil texture is an important factor, while in the Birrimian area, it is the steep nature of the terrain that induces erosion. The granitic soils are characteristically sandy and, as such, highly susceptible to erosion. Topsoil (10–30 cm) sand contents of three major soils developed over granite are over 80%. Severe erosion has reduced topsoil thickness by over 30% within a period of 24 years. Rainfall, though generally low (< 1000 mm), falls so intensely to break down soil aggregates thus accelerating erosion. Other observed indicators of land degradation include sealed and compacted topsoils, stones, gravel, concretions and iron pan. -

Rose E. Frisch Associate Professor of Population Sciences, Emerita Member, Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies

Rose E. Frisch Associate Professor of Population Sciences, Emerita Member, Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies Department of Global Health and Population 9 Bow Street Cambridge, MA 02138 617.495.3013 [email protected] Research My research has shown that undernutrition and intense physical activity can have a limiting effect on female fertility. Women who have too little body fat, because of injudicious dieting and/or intensive physical activity, also have disruption or impairment of their reproductive ability; they are infertile due to hypothalamic dysfunction which is correlated with weight loss or excessive leanness. The effect is reversible with gain in weight and fatness. Fat is an active metabolic tissue that makes estrogen, and as recently discovered, a hormone, leptin. Human reproduction has a metabolic cost: it takes about 50,000 calories over the daily caloric maintenance cost to grow a human infant to term. Lactation costs about 500-1000 calories a day. I hypothesized that a critical, minimum amount of body fat is necessary for, and directly influences, female reproduction. My research results are predictive and are now used clinically for evaluation of nutritional infertility and the restoration of fertility. Research on the long-term health of 5,498 U.S. college alumnae showed that moderate athletic regular activity resulted in a lower risk of breast cancer and cancers of the reproductive system and a lower risk of late onset diabetes. Environmental factors of nutrition, physical activity and disease can affect each reproductive milestone from menarche to menopause, hence as I have documented the natural fertility of populations. -

The Paper I This Collection Explore..The Sstratelies for Eq,Uality in Physical Edudation and Ithletics.-Marjorie Reguipiients Of

7777177-7.. .1) 019.931:. thysical, Education 'and ',Athletic84..Str.ategies fbr .,110iPting. Tit 1:e..IX'..Requirements...1.onforence , Proceed4igs...'anc/C0 ,titban 'Divertity .Seri0., ..NuMber 66, August. 1979:. .-- .'%#,A, 1N4T toTiON ColuMbia Uniit ,' New-York:0. N. Y. NIIC Clear 4enghouse.'on the Orban:.DisadvattagEd.,:.1-Col.umbia UniV., New' N.Y. Sex DesegregatiOn AsSistance .CenteSt, 1 : . ONS AGENCY National. Inst.. of 'Education, (DHEW), Wa.shIngton, D4C,; Office. of EdUcatiOn. (MIER., Washington; p4C. :.. OS .DATt... Aug-I-9' .. st" ..\ i8.... ONTRACT.. 1100.,-77,-,00,71 . ,.. ;NOTE:1 15p. ,,,i AVAI ihttLE FROMIntti.tute. for . Ur ba.n. and,MinOrity4Educitio.n, ,Box 40,, Tec4ers_college, .C.olum04.4 ariiv4rsity, NowYork,NeV.. York 10027.($5.00).. ... * . .. .. EDES 'PR.TcE... MFOI/PC01,40los' Postage. ., . DOCRIPTOES Athletics:: Elementary. SeCondary -Oucation; *Equal EducAtioi: strede'raVlegislatkon;..*Femiles:. *Physica_. .. .E.4-fication; Sex (Characterisi4ici);. Sex Inerences; . *Sex' Discrimination f'" 1DENTIFIE4-S *Title IX EdicatiOn Amendments 1972' 'ABSTRACT . The paperithis collection explore..the implicatl.ons of Title IX i (arms of,Oducational equity, analyze 'sex-related differences between -males and females., and outline sstratelies for eq,uality in physical edudation and ithletics.-Marjoriesome Blaufarb discusses.the physical and psYchological ine.guities that exist in -the traditional .approach, to physical'educlaticz which provides for separate .progratms 'for boys and girls., Borotby .Harris reviews. the state of research on physiological, sex differences and, emphirsizes ,the 'fact that observed- dif aliences are mediated by _apical. fitness 14vels rathethan by sex. ,k;*---Aiete 1-1449-T-43-Xert4nes the ala reguipiients of Title IX requlations lor physical education .and .athleticS and suggesti ways for- develdping suppertive Measures necessary to make com,pliance meaningf ul. -

The Culture and Consequences of Low Energy Availability in National

The Culture and Consequences of Low Energy Availability in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division One Female Distance Runners: A Mixed Methods Investigation by Traci L. Carson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Epidemiological Science) in The University of Michigan 2021 Doctoral Committee: Assistant Professor, Carrie A. Karvonen-Gutierrez, Chair Associate Professor, Philippa J. Clarke Professor, Sioban D. Harlow Professor, Kendrin Sonneville Research Associate Professor Brady T. West Professor, Ron Zernicke Traci L. Carson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0484-7252 © Traci L. Carson 2021 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to every female athlete who has struggled with an eating disorder. I hope this work begins to change the narrative for the next generation of “us”. ii Acknowledgments There are so many people who supported me throughout this dissertation process and made me excited to wake up every day to do this work. When I began my academic career at the University of Michigan in 2012, I could have never imagined that I would still be here (pursuing a career in science) eight years later. I look back fondly on PH200, the course that inspired me to pursue a career in public health, during my junior year of undergrad. First, I would like to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Carrie Karvonen-Gutierrez, for your incredible mentorship over the past three and a half years. I am grateful for the unwavering support and guidance you provided me in pursuing my independent research interests. You always knew when to push me and when to let me navigate the journey and make mistakes (to learn from) on my own.