Forei Gn Policy Under Military Rule in Ghana, 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

Newsletter JULY 2021

NewsLetter JULY 2021 HIGHLIGHTS UN provides independent monitoring young people’s businesses support to Ghana’s 2021 Population Supporting the national COVID-19 and Housing Census. UN supports the establishment of a response is core to our development Coordinated Mechanism on the Safety efforts. Youth Innovation for Sustainable De- of Journalists. velopment Challenge gives a boost to United Nations in Ghana - April - June 2021 COVID-19 RESPONSE Supporting the national COVID-19 response: Core to UN’s development efforts management, logistics, data the fight against the pandem- Ghana received its sec- management and operation- ic. Through the efforts of the ond batch of the AstraZen- al plans, field support super- United Nations Development eca COVID-19 vaccine from vision, and communications Programme (UNDP), medical the COVAX facility on 7th May and demand creation activities. supplies from the West African 2021. With this delivery of Health Organisation (WAHO) 350,000 doses, many Ghana- UNICEF conducted three sur- have been delivered. Funded by ians who received their first veys on knowledge, attitudes the German Government (BMZ), dose were assured of their and practices around COVID-19 the European Union, the Econom- second jab. The UN Children’s vaccination through telephone ic Community of West African Fund (UNICEF) facilitated their interviews and mobile interactive States (ECOWAS) and WAHO, safe transport from the Dem- voice responses across different these set of supplies, the second ocratic Republic of Congo. key groups. Per the survey, key bulk supplies to ECOWAS mem- concerns on vaccine hesitancy ber states, was procured by GIZ Since the launch of the vac- are around safety, efficacy and and UNDP. -

A Consociational Analysis of the Experiences of Ghana in West Africa (1992-2016) Halidu Musah

Democratic Governance and Conflict Resistance in Conflict-prone Societies : A Consociational Analysis of the Experiences of Ghana in West Africa (1992-2016) Halidu Musah To cite this version: Halidu Musah. Democratic Governance and Conflict Resistance in Conflict-prone Societies : A Conso- ciational Analysis of the Experiences of Ghana in West Africa (1992-2016). Political science. Université de Bordeaux, 2018. English. NNT : 2018BORD0411. tel-03092255 HAL Id: tel-03092255 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03092255 Submitted on 2 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR EN SCIENCE POLITIQUE DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX École Doctorale SP2 : Sociétés, Politique, Santé Publique SCIENCES PO BORDEAUX Laboratoire d’accueil : Les Afriques dans le monde (LAM) Par: Halidu MUSAH TITRE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE AND CONFLICT RESISTANCE IN CONFLICT-PRONE SOCIETIES: A CONSOCIATIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE EXPERIENCES OF GHANA IN WEST AFRICA (1992-2016) (Gouvernance démocratique et résistance aux conflits dans les sociétés enclines aux conflits: Une analyse consociationnelle des expériences du Ghana en Afrique de l'Ouest (1992-2016)). Sous la direction de M. Dominique DARBON Présentée et soutenue publiquement Le 13 décembre 2018 Composition du jury : M. -

Address to the Nation by President of the Republic, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, on Updates to Ghana's Enhanced Response to Th

ADDRESS TO THE NATION BY PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC, NANA ADDO DANKWA AKUFO-ADDO, ON UPDATES TO GHANA’S ENHANCED RESPONSE TO THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC, ON SUNDAY, 5TH APRIL, 2020. Fellow Ghanaians, Good evening. Nine (9) days ago, I came to your homes and requested you to make great sacrifices to save lives, and to protect our motherland. I announced the imposition of strict restrictions to movement, and asked that residents of the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area and Kasoa and the Greater Kumasi Metropolitan Area and its contiguous districts to stay at home for two (2) weeks, in order to give us the opportunity to stave off this pandemic. As a result, residents of these two areas had to make significant adjustments to our way of life, with the ultimate goal being to protect permanently our continued existence on this land. They heeded the call, and they have proven, so far, to each other, and, indeed, to the entire world, that being a Ghanaian means we look out for each other. Yes, there are a few who continue to find ways to be recalcitrant, but the greater majority have complied, and have done so with calm and dignity. Tonight, I say thank you to each and every one of you law-abiding citizens. Let me thank, in particular, all our frontline actors who continue to put their lives on the line to help ensure that we defeat the virus. To our healthcare workers, I say a big ayekoo for the continued sacrifices you are making in caring for those infected with the virus, and in caring for the sick in general. -

Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments Through 1996

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 constituteproject.org Ghana's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 1996 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:30 Table of contents Preamble . 14 CHAPTER 1: THE CONSTITUTION . 14 1. SUPREMACY OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 2. ENFORCEMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION . 14 3. DEFENCE OF THE CONSTITUTION . 15 CHAPTER 2: TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 4. TERRITORIES OF GHANA . 16 5. CREATION, ALTERATION OR MERGER OF REGIONS . 16 CHAPTER 3: CITIZENSHIP . 17 6. CITIZENSHIP OF GHANA . 17 7. PERSONS ENTITLED TO BE REGISTERED AS CITIZENS . 17 8. DUAL CITIZENSHIP . 18 9. CITIZENSHIP LAWS BY PARLIAMENT . 18 10. INTERPRETATION . 19 CHAPTER 4: THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 11. THE LAWS OF GHANA . 19 CHAPTER 5: FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 Part I: General . 20 12. PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 20 13. PROTECTION OF RIGHT TO LIFE . 20 14. PROTECTION OF PERSONAL LIBERTY . 21 15. RESPECT FOR HUMAN DIGNITY . 22 16. PROTECTION FROM SLAVERY AND FORCED LABOUR . 22 17. EQUALITY AND FREEDOM FROM DISCRIMINATION . 23 18. PROTECTION OF PRIVACY OF HOME AND OTHER PROPERTY . 23 19. FAIR TRIAL . 23 20. PROTECTION FROM DEPRIVATION OF PROPERTY . 26 21. GENERAL FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS . 27 22. PROPERTY RIGHTS OF SPOUSES . 29 23. ADMINISTRATIVE JUSTICE . 29 24. ECONOMIC RIGHTS . 29 25. EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS . 29 26. CULTURAL RIGHTS AND PRACTICES . 30 27. WOMEN'S RIGHTS . 30 28. CHILDREN'S RIGHTS . 30 29. RIGHTS OF DISABLED PERSONS . -

World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems

WORLD FACTBOOK OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS Ghana by Obi N.I. Ebbe State University of New York at Brockport This country report is one of many prepared for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice Systems under Grant No. 90-BJ-CX-0002 from the Bureau of Justice Statistics to the State University of New York at Albany. The project director for the World Factbook of Criminal Justice was Graeme R. Newman, but responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained in each report is that of the individual author. The contents of these reports do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Bureau of Justice Statistics or the U.S. Department of Justice. GENERAL OVERVIEW I. Political System. Ghana has a multi-party parliamentary government with an elected President who is both Chief of the executive branch and the Head of State. Ghana has a centralized government with local divisions in eleven regions. There is a single legislature in the country, consisting of the President and the National Assembly. Regional leaders report to the central government in the capital of Accra. The criminal justice system is centralized in that the government has control over the courts, prisons, judges, and police. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Inspector General of Police, and the Director of Prisons are all appointed by the government and serve the entire country. Ghana is a member of the organization for African Unity (OAU) and a member of Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). It joined the British commonwealth in 1960. 2. -

Simon Baynham, 'Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes? the Case of Nkrumah's National Security Service'

The Journal of Modern African Studies, 23, 1 (1985), pp. 87-103 Quis Custodiet Ipsos CustodesP: the Case of Nkrumah's National Security Service by SIMON BAYNHAM* FROM the ancient Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta to twentieth- century Bolivia and Zaire, from theories of development and under- development to models of civil-military relations, one is struck by the enormous literature on armed intervention in the domestic political arena. In recent years, a veritable rash of material on the subject of military politics has appeared - as much from newspaper correspondents reporting pre-dawn coups from third-world capitals as from the more rarefied towers of academe. Yet looking at the subject from the perspective of how regimes mobilise resources and mechanisms to protect themselves from their own security forces, one is struck by the paucity of empirically-based evidence on the subject.1 Since 1945, more than three-quarters of Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East have experienced varying levels of intervention from their military forces. Some states such as Thailand, Syria, and Argentina have been repeatedly prone to such action. And in Africa approximately half of the continent's 50 states are presently ruled, in one form or another, by the military. Most of the coups d'etat from the men in uniform are against civilian regimes, but an increasing proportion are staged from within the military, by one set of khaki-clad soldiers against another.2 The maintenance of internal law and order, and the necessary provision for protection against external threats, are the primary tasks of any political grouping, be it a primitive people surrounded by hostile * Lecturer in Political Studies, University of Cape Town, and formerly Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political and Social Studies, Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. -

Hitler's Doubles

Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos Fully-Illustrated Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles: Fully-Illustrated By Peter Fotis Kapnistos [email protected] FOT K KAPNISTOS, ICARIAN SEA, GR, 83300 Copyright © April, 2015 – Cold War II Revision (Trump–Putin Summit) © August, 2018 Athens, Greece ISBN: 1496071468 ISBN-13: 978-1496071460 ii Hitler’s Doubles Hitler’s Doubles By Peter Fotis Kapnistos © 2015 - 2018 This is dedicated to the remote exploration initiatives of the Stargate Project from the 1970s up until now, and to my family and friends who endured hard times to help make this book available. All images and items are copyright by their respective copyright owners and are displayed only for historical, analytical, scholarship, or review purposes. Any use by this report is done so in good faith and with respect to the “Fair Use” doctrine of U.S. Copyright law. The research, opinions, and views expressed herein are the personal viewpoints of the original writers. Portions and brief quotes of this book may be reproduced in connection with reviews and for personal, educational and public non-commercial use, but you must attribute the work to the source. You are not allowed to put self-printed copies of this document up for sale. Copyright © 2015 - 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Hitler’s Doubles The Cold War II Revision : Trump–Putin Summit [2018] is a reworked and updated account of the original 2015 “Hitler’s Doubles” with an improved Index. Ascertaining that Hitler made use of political decoys, the chronological order of this book shows how a Shadow Government of crisis actors and fake outcomes operated through the years following Hitler’s death –– until our time, together with pop culture memes such as “Wunderwaffe” climate change weapons, Brexit Britain, and Trump’s America. -

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

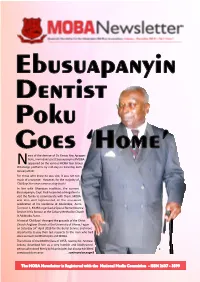

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc. -

Document of the International Fund for Agricultural Development Republic

Document of the International Fund for Agricultural Development Republic of Ghana Upper East Region Land Conservation and Smallholder Rehabilitation Project (LACOSREP) – Phase II Interim Evaluation May 2006 Report No. 1757-GH Photo on cover page: Republic of Ghana Members of a Functional Literacy Group at Katia (Upper East Region) IFAD Photo by: R. Blench, OE Consultant Republic of Ghana Upper East Region Land Conservation and Smallholder Rehabilitation Project (LACOSREP) – Phase II, Loan No. 503-GH Interim Evaluation Table of Contents Currency and Exchange Rates iii Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Map v Agreement at Completion Point vii Executive Summary xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Background of Evaluation 1 B. Approach and Methodology 4 II. MAIN DESIGN FEATURES 4 A. Project Rationale and Strategy 4 B. Project Area and Target Group 5 C. Goals, Objectives and Components 6 D. Major Changes in Policy, Environmental and Institutional Context during 7 Implementation III. SUMMARY OF IMPLEMENTATION RESULTS 9 A. Promotion of Income-Generating Activities 9 B. Dams, Irrigation, Water and Roads 10 C. Agricultural Extension 10 D. Environment 12 IV. PERFORMANCE OF THE PROJECT 12 A. Relevance of Objectives 12 B. Effectiveness 12 C. Efficiency 14 V. RURAL POVERTY IMPACT 16 A. Impact on Physical and Financial Assets 16 B. Impact on Human Assets 18 C. Social Capital and Empowerment 19 D. Impact on Food Security 20 E. Environmental Impact 21 F. Impact on Institutions and Policies 22 G. Impacts on Gender 22 H. Sustainability 23 I. Innovation, Scaling up and Replicability 24 J. Overall Impact Assessment 25 VI. PERFORMANCE OF PARTNERS 25 A. -

ACCOUNTING to the PEOPLE #Changinglives #Transformingghana H

ACCOUNTING TO THE PEOPLE #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana H. E John Dramani Mahama President of the Republic of Ghana #ChangingLives #TransformingGhana 5 FOREWORD President John Dramani Mahama made a pact with the sovereign people of Ghana in 2012 to deliver on their mandate in a manner that will change lives and transform our dear nation, Ghana. He has been delivering on this sacred mandate with a sense of urgency. Many Ghanaians agree that sterling results have been achieved in his first term in office while strenuous efforts are being made to resolve long-standing national challenges. PUTTING PEOPLE FIRST This book, Accounting to the People, is a compilation of the numerous significant strides made in various sectors of our national life. Adopting a combination of pictures with crisp and incisive text, the book is a testimony of President Mahama’s vision to change lives and transform Ghana. EDUCATION The book is presented in two parts. The first part gives a broad overview of this Government’s performance in various sectors based on the four thematic areas of the 2012 NDC manifesto.The second part provides pictorial proof of work done at “Education remains the surest path to victory the district level. over ignorance, poverty and inequality. This is self evident in the bold initiatives we continue to The content of this book is not exhaustive. It catalogues a summary of President take to improve access, affordability, quality and Mahama’s achievements. The remarkable progress highlighted gives a clear relevance at all levels.” indication of the President’s committment to changing the lives of Ghanaians and President John Dramani Mahama transforming Ghana. -

Page 1 of 143 Ventura County Library Diversity, Inclusion, & Anti

Ventura County Library Diversity, Inclusion, & Anti-RacismSort All Featured White Fragility By: DiAngelo, Robin; Dyson, Michael Eric ISBN: 9780807047422 Published By: Beacon Press 2018 EPUB3 View book URL https://ebook.yourcloudlibrary.com/library/venturacountylibrary-document_id-qv1u1r9 The New York Times best-selling book exploring the counterproductive reactions white people have when their assumptions about race are challenged, and how these reactions maintain racial inequality. In this “vital, necessary, and beautiful book” (Michael Eric Dyson), antiracist educator Robin DiAngelo deftly illuminates the phenomenon of white fragility and “allows us to understand racism as a practice not restricted to ‘bad people’ (Claudia Rankine). Referring to the defensive moves that white people make when challenged racially, white fragility is characterized by emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and by behaviors including argumentation and silence. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium and prevent any meaningful cross-racial dialogue. In this in-depth exploration, DiAngelo examines how white fragility develops, how it protects racial inequality, and what we can do to engage more constructively. Page 1 of 143 Let Them See You By: Braswell, Porter ISBN: 9780399581410 Published By: Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale 2019 The guide to getting hired, being promoted, and thriving professionally for the 40 million people of color in the workplace—fromthe CEO and cofounder of Jopwell, the leading career advancement platform for Black, Latinx, and Native American students and professionals. Let Them See You is a collection of Braswell’s straight-talking advice and mentorship for diverse careerists, from college students to mid-level professionals.