Democratizing Innovation and Capital Access: the ROLE of CROWDFUNDING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gedi Book V4.Indd

Forget the Glass Ceiling: Build Your Business Without One Geri Stengel Copyright © 2014 by Geri Stengel All rights reserved. Dedication To my mother and the other mothers who inspire their daughters by showing the way. My mother, Mickey, went back to work before it was acceptable — in the ‘60s. First as a bookkeeper in my grandfather’s hardware, houseware and toy store. Then as the owner, when she and my father opened their own store. When I graduated from college, I opted for the corporate world instead of running the family business. My mother would be delighted that I have since started my own business. She would be even more pleased that my business gives me the opportunity to write about the successes of women entrepreneurs to inspire the next generation. Thank you, Dell, for the opportunity to write about 10 awe-inspiring women who didn’t need to break glass, because they’re building businesses without ceilings. Contents Foreword i Introduction 1 Erika Bliss 5 Mandy Cabot 8 Luan Cox 11 Liz Elting 14 Kara Goldin 17 Lili Hall 20 Paula Long 23 Kourtney Ratliff 26 Danae Ringelmann 29 Nina Vaca 32 Networks fuel business growth 35 Ingredients for creating more high-potential women entrepreneurs 43 Financing: It is the best of times, it is the worst of times 51 Crowdfunding: A game-changer for women entrepreneurs 62 Innovation and growth aren’t just for the technology companies 67 Challenges to high-potential entrepreneurship and how to 73 overcome them Setting the stage for high-potential women entrepreneurs 80 No one “has it all” but you can have a lot 84 What’s needed to increase the trajectory of women-led businesses? 89 “You’ve come a long way, baby” 93 Foreword | i Foreword by Jennifer Jones “JJ” Davis Entrepreneurship is a key driver of a country’s prosperity and competitiveness. -

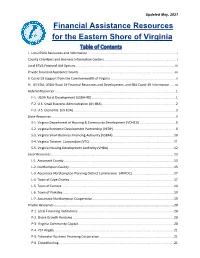

Financial Assistance Resources for the Eastern Shore of Virginia

Updated May 2019 Financial Assistance Resources for the Eastern Shore of Virginia Table of Contents Federal Resources ............................................................................................. 1 F-1. USDA Rural Development ........................................................................ 1 F-2. US Small Business Administration .......................................................... 2 F-3. US Economic Development Administration ............................................. 3 State Resources ................................................................................................ 5 S-1. VA Department of Housing & Community Development ......................... 5 S-2. VA Economic Development Partnership .................................................. 6 S-3. VA Small Business Financing Authority ................................................ 10 S-4. VA Tourism Corporation ........................................................................ 11 S-5. VA Housing Development Authority ...................................................... 12 Local Resources .............................................................................................. 13 L-1. Accomack County .................................................................................. 13 L-2. Northampton County .............................................................................. 15 L-3. Accomack-Northampton Planning District Commission ....................... 17 L-4. Town of Cape Charles ........................................................................... -

Financing Growth: a Practical Resource Guide for Small Businesses APRIL 2015

Financing Growth: A Practical Resource Guide for Small Businesses APRIL 2015 An Introduction to Capital Navigation Issues who have started companies in high-growth industries who are connected to incubators and accelerators. As such, we Small business growth and long-term success depend on focus primarily on equity capital because it is essential for securing sufficient capital at critical times in the business second stage growth and it is typically more difficult for small life cycle. According to a recent National Small Business businesses to find comparative information on alternative Association report (2014), more than 28 percent of small sources of equity than for debt capital. The lending market business owners are unable to obtain adequate financing.1 has also been effectively covered in several national and local A recent report from the Pepperdine Private Capital Markets resource guides.3 Although many emerging sources of capital Project (2015) finds that businesses that need capital and fail target social enterprises, this report is focused on for-profit to secure it experience slower revenue growth, hire fewer firms that do not self-identify as social enterprises. employees than planned and reduce their employee numbers.2 The barriers that small businesses face accessing capital are The resource guide was informed by a thorough review of the well documented. Small businesses need connections to a literature on small business capital and interviews with key pool of readily available capital and the capacity to effectively experts in the field, including leadership at financial organiza- compete for scarce resources. tions. The guide is divided into five sections: The purpose of this report is to address a separate, but related j Traditional private-sector capital sources (private equity, issue that is often overlooked: Businesses need to find the venture capital and angel investors), p. -

Cool Tech Startups in NYC - Modified Based on Mapped in NY Companies

Cool Tech Startups in NYC - Modified Based on Mapped In NY Companies Company Name Address URL Hiring "Document Prep- ' - ' Program"' "More than just ' - ' Figleaves' #Fit4ME' ' - ' 'brellaBox' ' - ' 'wichcraft' ' - ' (GFree)dom' ' - ' 0s&1s Novels' ' - ' 1 Knickerbocker' ' - ' 1 Main Street Capital' ' - ' 10 Speed Labs' '1239 Broadway' 1000|MUSEUMS, Inc' ' - ' 107 Models' ' - ' 10Lines' ' - ' 10gen' ' - ' 11 Picas' ' - ' 144 Investments' ' - ' 1754 & Company, LLC' ' - ' 1800Postcards.com' '121 Varick Street' 1800TAXISTA.COM ' - ' Page 1 of 514 10/02/2021 Cool Tech Startups in NYC - Modified Based on Mapped In NY Companies Jobs URL Page 2 of 514 10/02/2021 Cool Tech Startups in NYC - Modified Based on Mapped In NY Companies INC' 18faubourg by Scharly ' - ' Designer Studio' 1938 News' '1 Astor Pl' 1DocWay' '483 Broadway, Floor 2, New York, NY 10013' 1NEEDS1 LLC' ' - ' 1Stop Energies' ' - ' 1World New York' ' - ' 1er Nivel S.A.' ' - ' 1stTheBest Inc' ' - ' 1stdibs.com' '51 Astor Place' 20x200' '6 Spring Street' 24eight, LLC' ' - ' 24symbols' '42 West 24th Street ' 27 Perry' ' - ' 29th Street Publishing' ' - ' 2Cred' ' - ' 2J2L' ' - ' 2U (aka 2tor)' '60 Chelsea Piers, Suite 6020' 2findLocal' '2637 E 27th St' 2nd Nature Toys' ' - ' Page 3 of 514 10/02/2021 Cool Tech Startups in NYC - Modified Based on Mapped In NY Companies Page 4 of 514 10/02/2021 Cool Tech Startups in NYC - Modified Based on Mapped In NY Companies 303 Network, Inc.' ' - ' 33across' '229 West 28th Street, 12th Fl' 345 Design' '49 Greenwich Ave, Suite 2' A.R.T.S.Y Magazine' -

The Nuts and Bolts of Starting and Financing a Business

The Nuts and Bolts of Starting and Financing a Business Updated March 12, 2018 1 Give Women Credit: The Obstacles of Being a Woman in Business 3 A State-of-the-Art Toolbox 3 Create a Support Network 4 Find Appropriate Role Models 4 Establish Better Connectivity 5 Networking Groups 5 Get Social 5 Don’t Exclude Men 6 Close the Gap with Education 6 Take Courses 6 Get Certified 7 Seek Sage Counsel 7 Decode the Finance Game 8 Step 1: Identify the Need 8 Step 2: Know Your Options 8 Step 3: Deconstruct Your Needs 8 Step 4: Do Some Serious Homework 9 Step 5: Prepare Like Your Business Depends on It 9 Your Financing Options 9 Small Business or High-Growth Financing Options 10 Friends and Family 10 Government Small Business Grants 10 Competitions 11 Rewards-based Crowdfunding 12 Small Business Financing Options 13 Loans 13 Mainstream Crowdfunding 15 Regulation Crowdfunding 15 Raising Investment Dollars Within Your State via Crowdfunding 16 High-Growth Financing Options 16 Equity Financing 16 Angels 17 Crowdfunding for Accredited Investors 18 Venture Capital 19 Create a Winning Team 20 Success Is a Journey 20 Follow Your Own Road 20 2 Women couldn’t even apply for their own credit cards until 1974. Fast-forward two generations and today 39% of American businesses are owned by women, according to The 2017 State of Women-Owned Businesses commissioned by American Express. Being a woman in business comes with its fair share of challenges. This resource-rich ebook provides practical, actionable advice to help start a small business or a mega company with key insights into the funding options currently available for women in particular. -

Crowdfunding Your Fashion Business Resource Guide and Workbook for Emerging Fashion Brands

Crowdfunding Your Fashion Business Resource Guide and Workbook for Emerging Fashion Brands A collaboration between StartUp FASHION and Luevo Written by: Nicole Giordano and Ana Caracaleanu Book design: Sofie Rootenberg Table of Contents Introduction to Crowdfunding.............................................................................. 1 Is Crowdfunding Right for You?........................................................................... 7 Choosing Your Crowdfunding Platform.......................................................... 14 Preparing for Your Crowdfunding Campaign................................................ 22 Marketing Your Crowdfunding Campaign Before Your Launch............... 38 Marketing Your Live Crowdfunding Campaign............................................ 44 What to Do After your Campaign Has Closed............................................. 47 Tables and Oth er Appendixes Pre-Launch Campaign Checklist.....................................................53 Social Media Resources..................................................................... 54 Social Media Sample Posts...................................... 55 Email Templates..................................................................... 56 Project Budget Template..................................................................... 61 Fashion Industry Interviews...................................................................63 8 Tips for Positioning your Brand for Funding....................................73 12 Tips for Continued Business -

Financial Resources for the ESVA

Updated May, 2021 Financial Assistance Resources for the Eastern Shore of Virginia Table of Contents I. Local ESVA Resources and Information .................................................................................................. i County Chambers and Business Information Centers ................................................................................ i Local ESVA Financial Aid Options .............................................................................................................. iii Private Financial Assistance Grants .......................................................................................................... iv II. Covid-19 Support from the Commonwealth of Virginia ........................................................................ v III. US-EDA, USDA-Rural 19 Financial Resources and Development, and SBA Covid-19 Information...... vi Federal Resources ...................................................................................................................................... 1 F-1. USDA Rural Development (USDA-RD) ............................................................................................. 1 F-2. U.S. Small Business Administration (US SBA) .................................................................................. 2 F-3. U.S. Economic (US EDA) ................................................................................................................. 3 State Resources ......................................................................................................................................... -

Choosing an Equity Crowdfunding Platform

Prepared by Sponsored by everything ventured, everything gained Stand d ow Cr HE t OutIn How Women (and Men) Benefit From Equity Crowdfunding Geri Stengel President / Ventureneer SPONSORS SPONSORS i TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND VENTURENEER i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ii A INTRODUCTION 1 B EQUITY FINANCING AND WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS 8 C NEW OPPORTUNITIES FOR INVESTORS 15 D INVESTING IN WOMEN 31 E CHOOSING AN EQUITY CROWDFUNDING PLATFORM 48 F THE CONNECTION BETWEEN REWARDS-BASED CROWDFUNDING AND EQUITY CROWDFUNDING 54 G PREPARING FOR AN EQUITY CROWDFUNDING CAMPAIGN 59 H INVESTOR RELATIONS FOR TODAY’S TIMES 68 I PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER 85 J CLOSING THE CONFIDENCE GAP 90 K CONCLUSION 95 L THANK YOUS 98 ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND VENTURENEER Geri Stengel “A baby boomer with the heart and soul of a millennial” describes me best. I grew up believing that dedicated, thoughtful people can change the world by working together. I’m a believer still. I’m even more committed to the possibility of meaningful change because we have a huge, untapped resource: women! Give them the funding they need and they create jobs, innovate, and drive economic growth. So, for the last few years, I have researched and written about the challenges women face in the entrepreneurial world and the success factors that help them break through barriers, whether starting or scaling a business. My passion to get women on the radar as leaders of mega-firms led me to write Forget the Glass Ceiling: Build Your Business Without One, commissioned by Dell. Now, I’ve completed another research project, aimed at helping women entrepreneurs get the funding they need through crowdfunding. -

The Nonprofit End-Of-Year Resource Guide ______

The Nonprofit End-of-Year Resource Guide ________________________________________________________ From #GivingTuesday until New Year’s Eve, the end of the year is busy for nonprofits, and for good reason. On average, 30% of annual giving occurs in December, and 10% of annual giving occurs in the last 3 days of the year. To help you get the most out of this festive and generous month, we’ve compiled our favorite end-of-year campaign guides and resources into one handy bundle. Plus we’ve added some extra checklists and tips in there as a treat. What’s Inside? ________________________________________________________ The Basics Setting Goals for Fundraising Fundraising Tools Fundraising Email Best Practices and Templates The Asks Festive Ideas for Fundraising Emails A/B Testing Fundraising Emails The Thank-Yous Donor Thank You Email Best Practices and Examples Sending Major Thank You’s: Templates for Emailing Top Donors Thanking Donors Beyond Email Fundraising Tools ________________________________________________________ There are a lot of fundraising websites out there. In the time it took me to type that previous sentence, a new one probably just launched. With so much to choose from, it can be hard to tell where to start. We’ve looked at some donation platforms in the past, specifically as part of our recommendations for nonprofits looking to keep that steady drumbeat of on-site contributions. And we’re still big fans of those platforms — but for fundraising websites, we wanted to look at those instances where you have a specific niche to fill. In many cases, these complement a more robust CRM strategy. What type of fundraising website do I need? The answer to this depends on what you need from your online fundraising tools — you wouldn’t hire a major gifts officer to be your volunteer coordinator. -

Cool Tech Startups Hiring in NYC Based on Mapped in NY Companies

Cool Tech Startups Hiring in NYC Based on Mapped In NY Companies Company Name Address Address2 "Document Prep-Program"' ' - ' ' - ' "More than just Figleaves' ' - ' ' - ' #Fit4ME' ' - ' ' - ' 'brellaBox' ' - ' ' - ' 'wichcraft' ' - ' ' - ' (GFree)dom' ' - ' ' - ' 0s&1s Novels' ' - ' ' - ' 1 Knickerbocker' ' - ' ' - ' 1 Main Street Capital' ' - ' ' - ' 10 Speed Labs' '1239 Broadway' 'Penthouse' 1000|MUSEUMS, Inc' ' - ' ' - ' 107 Models' ' - ' ' - ' 10Lines' ' - ' ' - ' 10gen' ' - ' ' - ' 11 Picas' ' - ' ' - ' 144 Investments' ' - ' ' - ' 1754 & Company, LLC' ' - ' ' - ' 1800Postcards.com' '121 Varick Street' '4th Floor' 1800TAXISTA.COM INC' ' - ' ' - ' 18faubourg by Scharly Designer Studio' ' - ' ' - ' Page 1 of 717 10/02/2021 Cool Tech Startups Hiring in NYC Based on Mapped In NY Companies City Category Name URL ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' 'New York' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' ' - ' 'New York' ' - ' ' - ' Page 2 of 717 10/02/2021 Cool Tech Startups Hiring in NYC Based on Mapped In NY Companies Hiring Jobs URL Why NYC Page 3 of 717 10/02/2021 Cool Tech Startups Hiring in NYC Based on Mapped In NY Companies 1938 News' '1 Astor Pl' ' - ' 1DocWay' '483 Broadway, Floor 2, New York, NY '483 Broadway, Floor 2' 10013' 1NEEDS1 LLC' ' - ' ' - ' 1Stop Energies' ' - ' ' - ' 1World New York' ' - ' ' - ' 1er Nivel S.A.' ' - ' ' - ' 1stTheBest Inc' ' - ' ' - ' 1stdibs.com' '51 Astor Place' 'Third Floor' 20x200' '6 Spring Street' ' - ' 24eight, LLC' ' - ' ' - ' 24symbols' '42 West 24th Street ' ' - ' 27 Perry' ' - ' -

Are Early Stage Investors Biased Against Women?

Are Early Stage Investors Biased Against Women? Michael Ewens and Richard R. Townsend⇤ October 18, 2017 Abstract We examine whether male investors are biased against female entrepreneurs. To do so, we use a proprietary dataset from AngelList covering fundraising startups. We find that female founders are less successful with male investors compared to observably similar male founders. In contrast, the same female founders are more successful than male founders with female investors. The results do not appear to be driven by differences across founder gender in startup quality, sector focus, or risk. Given that investors are predominately male, our results suggest that an increase in female investors is likely necessary to support an increase in female entrepreneurship. ⇤Ewens: California Institute of Technology, [email protected]. Townsend: University of California, San Diego, Rady School of Business, [email protected]. The authors thank Kevin Laws of AngelList for graciously providing the data. The authors thank seminar participants at Arizona State University, Caltech, the Kauffman Emerging Scholars conference and the LBS Private Equity Symposium. We also thank Shai Bernstein, Juanita Gonzales-Uribe, Sabrina Howell, Arthur Korteweg, Ramana Nanda and David Neumark for comments. 1 Introduction It is well known that there is a significant gender gap in entrepreneurship. Recent studies of high-growth startup activity in the US find that only roughly 10-15% of startups are founded by women (Tracy, 2011; Brush et al., 2014; Gompers and Wang, 2017b). Many explanations for this phenomenon have been offered, including gender differences in technical training as well as differences in risk aversion.1 According to such explanations, women drop offfrom entrepreneurial career paths long before they reach the point of seeking financing from a venture capitalist (VC) or angel investor. -

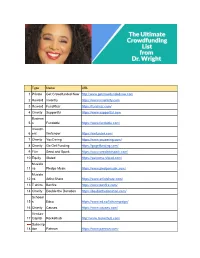

Type Name URL 1 Private Get Crowdfunded Now

Type Name URL 1 Private Get Crowdfunded Now http://www.getcrowdundednow.com 2 Reward Inventry https://www.inventrify.com 3 Reward FundRazr https://fundrazr.com/ 4 Charity Supportful https://www.supportful.com Busines 5 s Fundable https://www.fundable.com/ Investm 6 ent Wefunder https://wefunder.com/ 7 Charity YouCaring https://www.youcaring.com/ 8 Charity Go Get Funding https://gogetfunding.com/ 9 Film Seed and Spark https://www.seedandspark.com/ 10 Equity Slated https://welcome.slated.com/ Musicia 11 ns Pledge Music https://www.pledgemusic.com/ Musicia 12 ns Artist Share https://www.artistshare.com/ 13 T shirts Bonfire https://www.bonfire.com/ 14 Charity Double the Donation https://doublethedonation.com/ Schoool 15 s Edco https://www.ed.co/linkcampaign/ 16 Charity Causes https://www.causes.com/ Venture 17 Capital Rockethub http://www.rockethub.com/ Subscrip 18 tion Patreon https://www.patreon.com/ 19 Equity Circle up https://circleup.com/ 20 Loans Lending Club https://www.lendingclub.com Investor 21 s Crowdfunder https://www.crowdfunder.com/ Start Some Good (Facebook uses this 22 Charity one) https://startsomegood.com/ Hardwar 23 e Crowdf Supply https://www.crowdsupply.com/ Science 24 research Experiment https://experiment.com/ 25 Charity Chuffed https://www.chuffed.org/us 26 School Donors Choose https://www.donorschoose.org/ Real 27 Estate Peer Street https://www.peerstreet.com/ Real 28 Estate Real Crowd https://www.realcrowd.com/ 29 Charity Classy https://www.classy.org/ Real 30 Estate Realty Mogul https://www.realtymogul.com/ Weddin