Examining Interventions to Address Infant Mortality in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin

1 FINAL REPORT-NORTHSIDE PITTSBURGH-Bob Carlin-submitted November 5, 1993 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I Fieldwork Methodology 3 II Prior Research Resources 5 III Allegheny Town in General 5 A. Prologue: "Allegheny is a Delaware Indian word meaning Fair Water" B. Geography 1. Neighborhood Boundaries: Past and Present C. Settlement Patterns: Industrial and Cultural History D. The Present E. Religion F. Co mmunity Centers IV Troy Hill 10 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. The Fichters 2. Czech/Bohemian D. Community Celebrations V Spring Garden/The Flats 14 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity VI Spring Hill/City View 16 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German D. Community Celebrations VII East Allegheny 18 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. German a. Churches b. Teutonia Maennerchor 2. African Americans D. Community Celebrations E. Church Consolidation VIII North Shore 24 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Heinz House D. Ethnicity 1. Swiss-German 2. Croatian a. St. Nicholas Croatian Roman Catholic Church b. Javor and the Croatian Fraternals 3. Polish IX Allegheny Center 31 2 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Community Center: Farmers' Market D. Ethnicity 1. Greek a. Grecian Festival/Holy Trinity Church b. Gus and Yia Yia's X Central Northside/Mexican War Streets 35 A. Industrial and Cultural History B. The Present C. Ethnicity 1. African Americans: Wilson's Bar BQ D. Community Celebrations XI Allegheny West 36 A. -

University of Pittsburgh Heinz Field Event Bus Staging Instruction

University of Pittsburgh Heinz Field Event Bus Staging Instruction Discharge passengers at 3 Reedsdale Street 15212 (stadium side) prior to Art Rooney Avenue o GPS: 40.4481192, -80.0164596 Immediately move bus to 1301 Beaver Avenue 15233 (driving directions follow) o GPS: 40.452895, -80.029151 Remain on Beaver Avenue until escorted by University of Pittsburgh Police back to the stadium where you will park at 400 North Shore Drive 15212. This will occur approx. 30 minutes after kick-off. o GPS: 40.445427, -80.013206 Make certain that “PITT Event Bus” sign is prominently displayed in vehicle’s front window at all times. Driving Directions: Reedsdale Street to Beaver Avenue Proceed east on Reedsdale Street past Art Rooney Avenue and Tony Dorsett Drive. Turn right onto Mazeroski Way, go through the West General Robinson Street intersection, and turn right onto North Shore Drive. Proceed west on North Shore Drive around the stadium, past Gate C, onto Allegheny Avenue. Continue on Allegheny Avenue turn left at the 7-11 convenience store onto Western Avenue. Proceed on Western Avenue which becomes Chateau Street (right lane). Proceed on Chateau Street to the end and turn left under the bridge onto Beaver Avenue. Proceed three blocks and stop at Pennsylvania Avenue (1301 Beaver Avenue 15233), just past the Mack Truck Company o GPS: 40.452895, -80.029151 Do not advance past Pennsylvania Avenue. Remain at that location, along the right curb, until escorted by University of Pittsburgh Police back to North Shore Drive; which will occur -

The One Northside Community Plan

Strategy Guide No. 1 Sharing New Methods˙ to IMPACT Pittsburgh’s Neighborhoods innovative project report: THE ONE NORTHSIDE COMMUNITY PLAN Our mission is to support the people, organizations and partnerships committed to creating and maintaining thriving neighborhoods. We believe that Pittsburgh’s future is built upon strong neighborhoods and the good work happening on the ground. It is integral to our role as an advocate, collaborator and convener to lift up exemplary projects and share best practices in ways that advance better engagement and community-led decisions and ensure a better understanding of the processes that lead to success and positive impact on our neighborhoods. We share this story with you to inspire action and celebrate progress, and most importantly, to empower leaders and residents in other communities to actively ˙ shape the future of their neighborhoods. — Presley L. Gillespie President, Neighborhood Allies Neighborhood Strategy Guide || 1 innovative project report: From concept to consensus Upwards of 600 people braved the chill of an early December night in Pittsburgh last year to celebrate in the warmth inside Heinz Field, home of the Pittsburgh Steelers. Their reason for celebration had nothing to do with the exploits of the city’s beloved professional football team. A community plan was being unveiled for improving the quality of life in the city’s Northside neighborhoods around the stadium that the voices of several thousand residents and community stakeholders had shaped. And hopes were high that improvements in infrastructure, schools, employment and lives would be more broadly and quickly realized, as they had in other city neighborhoods where resources and revitalization were attracting investment and people. -

Affordable Housing Task Force Recommendations

Affordable Housing Task Force Findings and Recommendations to Mayor William Peduto and the Pittsburgh City Council May 2016 AHTF - Findings And Recommendations 1 The Affordable Housing Task Force began with an assumption that there was a compelling need to ad- dress the changing landscape of housing affordability in Pittsburgh. Through research, discussion, and community and stakeholder engagement, the Task Force has arrived at recommendations that respond to both the assumption and the realities of affordable housing in the city. The Task Force members, drawn from across the city, with a wide range of expertise and experience, worked through these issues in committees and working groups. They drew on the knowledge of ad- vocates, developers, and national experts, including the Needs Assessment study by Mullin & Lonergan and the Feasibility study by Peninger Consulting, and most importantly the communities of Pittsburgh. The Task Force participated directly in the community forums, organized with The Art of Democracy, held throughout the city. In those community forums, we heard strong concerns for today, and for the future. On the one hand, there are neighborhoods that are still experiencing disinvestment and decline, eager for new investment. On the other, there were concerns that the rapid increase in rent and home values were putting people, from families starting out to seniors, at risk of having to leave their neighborhoods. In response, the Task Force focused on major opportunities, both drawing on existing programs and proposing new approaches: a Pittsburgh Housing Trust Fund; better utilization of Low Income Housing Tax Credits; and Preservation of Existing Affordable Housing and Protecting Residents. -

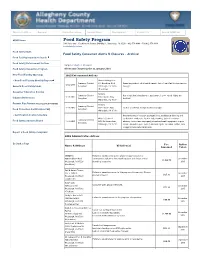

Food Safety Program

Director's Office Bureaus Clinics/Locations Recent News Employment Contact Us Search ACHD.net ACHD Home Food Safety Program 3901 Penn Ave., Clack Health Center, Building 1, Pittsburgh, PA 15201 • 412-578-8044 • FAX 412-578-8190 [email protected] Food Safety Main Food Safety Consumer Alerts & Closures - Archive Food Facility Inspection Search Food Safety Enforcement Actions Jump to: Alerts | Closures Food Safety Inspection Program Alerts and Closures prior to January 2016 New Food Facility Openings 2015 Enforcement Actions • New Food Facility Monthly Report Hank's Hotdogs Too Summary Criminal 919 Brookline Blvd. Operating without valid health permit, lack of certified food protection 12-22-2015 General Food Safety Links Complaint Pittsburgh, PA 15226 manager. (Brookline) Consumer Education & Links Fellini's Summary Criminal Use of residential equipment, equipment in poor repair, lights not 12-10-2015 1624 Lincoln Way Industry References Complaint shielded. White Oak, PA 15131 Permits Plan Review [Opening a New Food Biz] Fellini's Summary Criminal 12-10-2015 1624 Lincoln Way Lack of a certified food protection manager. Food Protection Certification FAQ Complaint White Oak, PA 15131 • Certification Course Schedule Unsafe thawing of vacuum packaged food, inadequate cleaning and Miller’s Seafood sanitization of utensils, lack of date-marking, lack of consumer Summary Criminal Food Safety Advisory Board 11-18-2015 3853 California Ave. advisory, toxic items improperly stored and used, equipment in poor Complaint Pittsburgh, PA 15212 repair, dumpster open, lack of shielded lights, excessive clutter, lack of appropriate waste receptacle Report a Food Safety Complaint 2015 Administrative Actions Go Back a Page Fee Action Name & Address Violation(s) Assessed Taken SMOQ Pitt Failure to submit construction plans for approval prior to 600 Brookline Blvd. -

City of Pittsburgh Neighborhood Profiles Census 2010 Summary File 1 (Sf1) Data

CITY OF PITTSBURGH NEIGHBORHOOD PROFILES CENSUS 2010 SUMMARY FILE 1 (SF1) DATA PROGRAM IN URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND URBAN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH JULY 2011 www.ucsur.pitt.edu About the University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) The University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) was established in 1972 to serve as a resource for researchers and educators interested in the basic and applied social and behavioral sciences. As a hub for interdisciplinary research and collaboration, UCSUR promotes a research agenda focused on the social, economic and health issues most relevant to our society. UCSUR maintains a permanent research infrastructure available to faculty and the community with the capacity to: (1) conduct all types of survey research, including complex web surveys; (2) carry out regional econometric modeling; (3) analyze qualitative data using state‐of‐the‐art computer methods, including web‐based studies; (4) obtain, format, and analyze spatial data; (5) acquire, manage, and analyze large secondary and administrative data sets including Census data; and (6) design and carry out descriptive, evaluation, and intervention studies. UCSUR plays a critical role in the development of new research projects through consultation with faculty investigators. The long‐term goals of UCSUR fall into three broad domains: (1) provide state‐of‐the‐art research and support services for investigators interested in interdisciplinary research in the behavioral, social, and clinical sciences; (2) develop nationally recognized research programs within the Center in a few selected areas; and (3) support the teaching mission of the University through graduate student, post‐ doctoral, and junior faculty mentoring, teaching courses on research methods in the social sciences, and providing research internships to undergraduate and graduate students. -

An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County

Research Report Moving to Opportunity or Disadvantage? An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County March 2020 The Allegheny County Department of Human Services One Smithfield Street Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222 www.alleghenycountyanalytics.us Basic Needs | An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County | March 2020 page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Figures and Tables 5 Definitions 6 Acronyms 7 Introduction 7 Background 7 Methodology 11 Limitations 15 Analysis 15 Demographics of Rental Subsidy Participants 15 HCV Households by Level of Disadvantage (move-in date 2017) 16 RRH Households by Level of Disadvantage (move-in date 2017) 18 Insights from Both Programs 20 Subsidized Housing Distribution in City of Pittsburgh versus Suburban Census Tracts 22 County-Wide Distribution of Households Living in Areas of High or Extreme Disadvantage 24 Moving Patterns Among HCV Households over Time 26 Discussion and Next Steps 27 APPENDIX A: HCV and RRH Program Details 30 APPENDIX B: Community Disadvantage Indicators and Sources 32 APPENDIX C: Allegheny County Census Tracts by Level of Disadvantage 33 APPENDIX D: Allegheny County Census Tracts by Disadvantage with Municipal Borders and Labels 34 APPENDIX E: Allegheny County Census Tracts by Disadvantage with City of Pittsburgh Neighborhoods and Labels 35 www.alleghenycountyanalytics.us | The Allegheny County Department of Human Services Basic Needs | An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County | March 2020 page 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Decades of social science research show that place has a profound influence on child-to-adult outcomes and this finding has far-reaching implications for how affordable housing policy should be designed and implemented. -

The Manchester Neighborhood Plan

The Manchester Neighborhood Plan Introduction & Methodology In the summer of 2009, the Manchester Citizens Corporation (MCC) Board of Directors partnered with Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation (PHLF) to commission a neighborhood planning process. The decision to undertake a planning process reflected a number of issues including the recognition that MCC’s existing planning documents were out of date with respect to reflecting the existing conditions in the neighborhood, and the desire to respond to increasing demolitions in Manchester in a proactive manner. MCC felt that the elements of a neighborhood wide strategy were embodied in the organization’s current development projects, but needed to be enhanced and articulated as part of a neighborhood planning process. MCC and PHLF desired to create a plan that is a dynamic rather than a static document. As a result, the planning process focused on establishing strategic principles and guidelines that would not change, even as the condition of individual parcels in the neighborhood changed. Although the Plan includes some parcel-specific recommendations, the plan is designed to focus more on overarching principles and guidelines. The Plan’s focus is on vacant and abandoned property. This is a critical issue as identified by Manchester residents and it is supported by data that indicate Manchester has a significant number of vacant properties. Vacant property poses a threat to public safety and the integrity of Manchester’s historic district. Dealing with the issue of vacant property in a systematic and well thought out manner is an objective of this Plan. The goals of this Plan relate to improving the physical and market conditions in the Manchester. -

Historic and Cultural Resource Plan

CHAPTER 4 HISTORIC AND CULTURAL RESOURCE PLAN I HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT The region was inhabited by the Delaware, Seneca, Shawnee and Mingo peoples when European traders and trappers As discussed earlier in Chapter Three, the growth of arrived to work along the County’s rivers. Native Americans Allegheny County and its communities has been strongly were largely nomadic, hunting and gathering food for influenced by the Three Rivers, abundant natural resources – survival. However, a few permanent settlements were especially high quality bituminous coal deposits – and established along the rivers, notably Shannopin’s Town proximity to major transportation routes. (a Delaware village near present-day Lawrenceville), Logstown (present-day Ambridge), and Chartier’s Old Town Hundreds of millions of years ago, the land that would (a Shawnee village in present-day Tarentum). Their homes become Allegheny County was covered by a shallow were built of log huts and bark. The Native Americans ocean. The flat sea floor was uplifted and altered by bartered with fur traders from England and France, trading erosion, resulting in a landscape characterized by steep beaver pelts for goods such as salt, blankets, guns and hills with relatively narrow ridge tops and steep-sided valleys. gunpowder. The French took care to befriend the Indians, The Allegheny and Monongahela rivers converged to form a friendship that would become very important. the Ohio River. Through geologic time these rivers carved the Allegheny Plateau into the rugged terrain of today. THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR The land is underlain by limestone, sandstone, shale and coal, which helped to fuel the emergence of our County’s “As I got down before the Canoe, I spent some Time in industry in the late 19th century. -

Greenways for Pittsburgh 2.0 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE GUIDE

Greenways for PittsburgH 2.0 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE GUIDE This Guide will act as your workbook as we progress through this project, and will continually be added too with each Management Committee meeting as a tool to track the project, thoughts, and ideas along the way. Please hold onto me and bring me to each project meeting. GREENWAYS FOR PITTSBURGH 2.0 background Greenways for Pittsburgh (1980) Offered a strategy; consolidation of public land, promotion of private property gifts, initial cleanup and single-agency management of these passive open space resources in co- operation with neighborhoods sensitive to their benefi ts. Documents: • The Greenway Brochure • The initial program schedule/status report • Generalized Land Use Map • The Vacant and Environmentally Sensitive Areas Map “The Greenway Program will make Pittsburgh a more livable City Code: Article XI - Parks and Playgrounds city by preserving our hillsides as a major open space amen- § 471.01 - CONTROL AND SUPERVISION BY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECRE- ity for our citizens. In these times of shrinking resources, ATION. tight budgets and due to the lack of large vacant land tracts, The Department of Parks and Recreation shall be responsible for the control and the development of major new parks is unlikely. However, supervision of all city recreational facilities including but not limited to parks, play- while the Greenways will not be developed as active parks, grounds, ballfi elds, dedicated greenways, and recreation centers. For purposes of this they will provide for protection of environmental sensitive ar- Title, a greenway is defi ned as a permanent, passive open space that serves to benefi t eas of our city in their natural state for passive use and the adjacent neighborhoods and the general public that is either dedicated or being studied enjoyment of future generations. -

Department of City Planning NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNER BIOS

Department of City Planning NEIGHBORHOOD PLANNER BIOS ANDREW DASH, AICP Andrew is the Assistant Director of neighborhoods and currently calls South Oakland home. In her free Strategic Planning for the City of time, Andrea enjoys exploring Pittsburgh’s parks, museums and Pittsburgh. He manages a team of 12 libraries with her husband and their two small, disproportionately fast planners, who handle long-range children. planning activities for the City, including: the development of the ASHLEY HOLLOWAY City’s first comprehensive plan, neighborhood planning, Ashley R. Holloway is a Neighborhood transportation planning, planning for Planner who hails from Cleveland, persons with disabilities, and Ohio. The neighborhoods Ashley environmental and open space covers are South Side Flats & Slopes, planning activities. In addition to his the Hilltop, and South Hills. Ashley duties as a planner, Andrew served as earned his Bachelor of Science degree a member of the Mayor’s Land in Community & Regional Planning Recycling Task Force, which drove the creation of the Pittsburgh Land from Iowa State University in 2005 Bank, and serves as a board member to the Pittsburgh Housing and has worked for the Department Development Corporation and the Allegheny Commons Initiative. since 2011. Andrew has spent the last 13 years as a planner, working at Marshall Before coming on as a Neighborhood Township (Allegheny County), the Mercer County Regional Planning Planner, Ashley worked as a Health Commission, and the City of Akron before joining the City over 6 Inspector for the City of Cleveland, years ago. When he’s not at the office, you’ll find Andrew out on his a Family Liaison for the Cleveland bike exploring the city, hiking in the wilderness, slowly renovating his Metropolitan School District, and a District Executive for the Boys 1880’s Italianate row house or playing at home or in the park with his Scouts of America, Cleveland office. -

Profile of Change in the City of Pittsburgh

PROFILE OF CHANGE IN THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH COMPARISON OF 2009‐2013 AND 2014‐2018 AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY (ACS) ESTIMATES FOR THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH AND NEIGHBORHOODS PROGRAM IN URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND URBAN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH JANUARY 2020 PROFILE OF CHANGE IN THE CITY OF PITTSBURGH – JANUARY 2020 Table of Contents Data and Methodology ............................................................................................ 2 Population Trends in the City of Pittsburgh ............................................................. 3 Age ........................................................................................................................ 4 Race ...................................................................................................................... 5 Educational Attainment ........................................................................................ 7 Commuting ........................................................................................................... 8 Housing Tenure ..................................................................................................... 9 Poverty ................................................................................................................ 10 Veterans .............................................................................................................. 11 Data Profiles ..........................................................................................................