United Nations Conflict Prevention and Preventive Diplomacy in Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butcher, W. Scott

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WILLIAM SCOTT BUTCHER Interviewed by: David Reuther Initial interview date: December 23, 2010 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Dayton, Ohio, December 12, 1942 Stamp collecting and reading Inspiring high school teacher Cincinnati World Affairs Council BA in Government-Foreign Affairs Oxford, Ohio, Miami University 1960–1964 Participated in student government Modest awareness of Vietnam Beginning of civil rights awareness MA in International Affairs John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies 1964–1966 Entered the Foreign Service May 1965 Took the written exam Cincinnati, September 1963 Took the oral examination Columbus, November 1963 Took leave of absence to finish Johns Hopkins program Entered 73rd A-100 Class June 1966 Rangoon, Burma, Country—Rotational Officer 1967-1969 Burmese language training Traveling to Burma, being introduced to Asian sights and sounds Duties as General Services Officer Duties as Consular Officer Burmese anti-Indian immigration policies Anti-Chinese riots Ambassador Henry Byroade Comment on condition of embassy building Staff recreation Benefits of a small embassy 1 Major Japanese presence Comparing ambassadors Byroade and Hummel Dhaka, Pakistan—Political Officer 1969-1971 Traveling to Consulate General Dhaka Political duties and mission staff Comment on condition of embassy building USG focus was humanitarian and economic development Official and unofficial travels and colleagues November -

The Role of U.S. Women Diplomats Between 1945 and 2004 Rachel Jane Beckett

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 The Role of U.S. Women Diplomats Between 1945 and 2004 Rachel Jane Beckett Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE ROLE OF U.S. WOMEN DIPLOMATS BETWEEN 1945 AND 2004 BY RACHEL JANE BECKETT A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Rachel Beckett defended on December 10, 2008. ____________________________________ Suzanne Sinke Professor Directing Thesis ____________________________________ Charles Upchurch Committee Member ___________________________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables iv Abstract v INTRODUCTION 1 1. ACCOMPLISHED BUT STILL LAGGING BEHIND 13 2. “PERCEPTION” AS THE STANDARD 29 3. STRATEGICAL GATEKEEPERS 48 CONCLUSION 68 REFERENCES 74 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 83 iii LIST OF TABLES Table 1.1 Degree Type 17 Table 1.2 Degree Concentration 17 Table 1.3 Number of Foreign Languages Spoken 18 Table 1.4 Type of Languages Spoken 19 Table 1.5 Female Chiefs of Mission by Region, 1933-2004 27 Table 2.1 Where Female Ambassadors are Most Frequently Assigned 34 Table 2.2 Percent of Women in National Legislatures, by region, 1975-97 35 Table 2.3 Appointment of Women as Chiefs of Mission and to other Senior Posts by Administration, 1933-2004 44 iv ABSTRACT Though historical scholarship on gender and international relations has grown over the last few decades, there has been little work done on women in the Foreign Service. -

Preventive Diplomacy by Intergovernmental Organizations: Learning from Practice

International Negotiation 17 (2012) 349–388 brill.com/iner Preventive Diplomacy by Intergovernmental Organizations: Learning from Practice Eileen F. Babbitt*, 1 !e Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, 160 Packard Avenue, Medford, MA 02155, USA (E-mail: [email protected]) Received 29 July 2012; accepted 12 August 2012 Abstract Conflict prevention is enjoying a renaissance in international policy circles. However, the official machin- ery of the international community presently offers few institutions with a specific mandate to address the causes of political violence at an early stage. One such multilateral mechanism dedicated solely to the prevention of conflict is the High Commissioner on National Minorities (HCNM) of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Over two decades, the office has developed a signifi- cant track record of effectiveness against which to examine the preventive efforts of other intergovern- mental organizations. In this article, we examine the prevention efforts of the HCNM in Georgia, Macedonia, and Ukraine and compare these with the preventive diplomacy of three other intergovern- mental organizations (IGOs): the Organization of American States (OAS) in Guyana, the Common- wealth in Fiji, and the UN in Afghanistan, Burundi, and Macedonia. Our findings offer some useful and surprising insights into effective prevention practice, with implications for how IGOs might improve preventive diplomacy in the future. *) Eileen F. Babbitt is Professor of Practice in international conflict management, Director of the Inter- national Negotiation and Conflict Resolution Program, and co-director of the Program on Human Rights and Conflict Resolution at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. -

Of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: a Claims Fund Proposal

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham International Law Journal Volume 4, Issue 1 1980 Article 6 Compensation for “Victims” of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: A Claims Fund Proposal R. Scott Garley∗ ∗ Copyright c 1980 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Compensation for “Victims” of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: A Claims Fund Proposal R. Scott Garley Abstract This Note will briefly trace the development of diplomatic immunity law in the United States, including the changes adopted by the Vienna Convention, leading to the passage of the DRA in 1978. The discussion will then focus upon the DRA and point out a few of the areas in which the statute may fail to provide adequate protection for the rights of private citizens in the United States. As a means of curing the inadequacies of the present DRA, the feasibility of a claims fund designed to compensate the victims of the tortious and criminal acts of foreign diplomats in the United States will be examined. COMPENSATION FOR "VICTIMS" OF DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY IN THE UNITED STATES: A CLAIMS FUND PROPOSAL INTRODUCTION In 1978, Congress passed the Diplomatic Relations Act (DRA)1 which codified the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Rela- tions. 2 The DRA repealed 22 U.S.C. §§ 252-254, the prior United States statute on the subject,3 and established the Vienna Conven- tion as the sole standard to be applied in cases involving the immu- nity of diplomatic personnel4 in the United States. -

Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus

Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus DECEMBER 2011 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Ban Ki-moon (left) is received by Guillaume Soro, Prime Minister of IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many donors, whose Côte d'Ivoire, at Yamoussoukro support makes publications like this one possible. In partic - airport. May 21, 2011. © UN ular, IPI would like to thank the governments of Finland, Photo/Basile Zoma. Norway, and Sweden for their generous contributions to The views expressed in this paper IPI's Coping with Crisis Program. Also, IPI would like to represent those of the authors and thank the Mediation Support Unit of the UN Department of not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Political Affairs for giving it the opportunity to contribute welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit to the process that led up to the Secretary-General's report of a well-informed debate on critical on preventive diplomacy. policies and issues in international affairs. IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor and Senior Fellow Marie O’Reilly, Publications Officer Suggested Citation: Francesco Mancini, ed., “Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus,” New York: International Peace Institute, December 2011. © by International Peace Institute, 2011 All Rights Reserved www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Francesco Mancini Preventive Diplomacy in Africa: Adapting to New Realities . 4 Fabienne Hara Optimizing Preventive-Diplomacy Tools: A Latin American Perspective . 15 Sandra Borda Preventive Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: Redefining the ASEAN Way . 28 Jim Della-Giacoma Preventive Diplomacy on the Korean Peninsula: What Role for the United Nations? . 35 Leon V. -

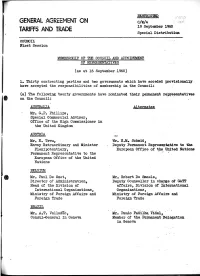

General Agreement on Tariffs And

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON c/wA TARIFFS AND TRADE 19 September 1960 Special Distribution COUNCIL First Session MEMBERSHIP OF THE COUNCIL AND APPOINTMENT OF REPRESENTATIVES (as at 16 September 1960} 1. Thirty contracting parties and two governments which have acceded provisionally have accepted the responsibilities of membership in the Council: (a) The following twenty governments have nominated their permanent representatives on the Council: AUSTRALIA Alternates Mr. G.P. Phillips, Special Commercial Adviser, Office of the High Commissioner in the United Kingdom AUSTRIA ac Mr, E. Treu, Mr. E.M. Schmid. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Deputy Permanent Representative to the Plenipotentiary, European Office of the United Nations Permanent Representative to the European Office of the United Nations BELGIUM Mr. Paul De Smet, Mr. Robert De Smaele, Director of Administration, Deputy Counsellor in charge of GATT Head of the Division of affairs, Division of International International Organizations, Organizations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade Foreign *rade BRAZIL Mr, A.T. Valladao, Mr. Paulo Padilha Vidal, ' Consul-General in Geneva Member of the Permanent Delegation in Geneva C/W/4 Page 2 Alternates CANADA Mr. J.H» Warren, Assistant Deputy Minister, Department of Trade and Commerce CHILE H.E. Mr. F. Garcia Oldini, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary in Switzerland CUBA H.E. Dr. E. Camejo-Argudin, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Head of the Permanent Mission to the inter national organizations in Geneva CZECHOSLDVAKIA Dr. Otto Benes, Economic Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the European Office of the United Nations DENMARK ecu Mr. N»V. Skak-Nielsen, Minister Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative to the international organizations in Geneva FINLAND Mr. -

Legation, Mmebre M .J Woulbruon (Belgique), De La Délégation Per- Manneet Belge Auprès Del' ONU Membre M

UNRESTRICTED INTERIM COMMISSION COMMISSION INTERIMAIRE DE ICITO/EC. 2/INF.2 FOR THE INTERNATIONAL L'ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE 25 August 1948 TRADE ORGANIZATION DU COMMERCE ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Executive Committee Comité Exécutif Second Session Deuxiéme Session LIST OF DELEGATES - LISTE DES DELEGUES Mr. J. A Tonkin, Leader Mr. J. Fletcher Mr. J. Russell Mr. c.L. S. Hewitt Mr.G. Warwick Smith Miss Judith Bearup, Stenographer Miss N. C. Stack, Stenographer Miss Mary Heffer, Stenographer Benelux M. Max Suetens, Ministre Plénipotentiaire et Envoyé Extraordinaire , Président D.r .A. .B Speekenbrink,Directeur Général du Commerce Extérieur, Vice-President Male Professeur .E Devries (territoires néerlandais d'outre-mer), Mmebre M.G. Cassiers (Belgique), Premier Secrétaire de Legation, Mmebre M .J Woulbruon (Belgique), de la Délégation per- manneet belge auprès del' ONU Membre M. Indekeu (Belgique), Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, , Adviser Dr. G. A. L amsvelt, (Netherlands) , Adviser Dr. J. Boehstal, (Netherlands), Secretary Brazil Ambassador Joao Muniz, Chief Delegate Eduardo Lopes Rodrigues, Delegate M. Roberto de Oliveira Campos, Adviser M. Oswaldo Behn Franco, Secretary Miss Maria Ilvà Pinto Ayres, Stenographer Miss Maria José Argollo, Stenographer Canada Hon. L.D. Wilgress, Canadian Ambassador to Switzerland, Chairman Mr. L.E. Couillard, Departrnent of Trade and Commerce Mr. S.S. Reisman, Department of Finance Miss Marion Henson, Secretary to Mr. Wilgress China Dr. Wunsz King, Leader Mr. Chi Chu, Delegate Mr. H.S. Hsu, Adviser Mr. S.M. Kao, Adviser Mr. C.L.. Pang, Secretary Miss Gloria Rosen, Stenographer Colombia Dr. Alfonso Bonilla Gutierrez, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, Senator of the Republic Dr. Camilo de Brigard Silva, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary Dr. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

De Facto and De Jure Annexation: a Relevant Distinction in International Law? Israel and Area C: a Case Study

FREE UNIVERSITY OF BRUSSELS European Master’s Degree in Human Rights and Democratisation A.Y. 2018/2019 De facto and de jure annexation: a relevant distinction in International Law? Israel and Area C: a case study Author: Eugenia de Lacalle Supervisor: François Dubuisson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, our warmest thanks go to our thesis supervisor, François Dubuisson. A big part of this piece of work is the fruit of his advice and vast knowledge on both the conflict and International Law, and we certainly would not have been able to carry it out without his help. It has been an amazing experience to work with him, and we have learned more through having conversations with him than by spending hours doing research. We would like to deeply thank as well all those experts and professors that received an e-mail from a stranger and accepted to share their time, knowledge and opinions on such a controversial topic. They have provided a big part of the foundation of this research, all the while contributing to shape our perspectives and deepen our insight of the conflict. A list of these outstanding professionals can be found in Annex 1. Finally, we would also like to thank the Spanish NGO “Youth, Wake-Up!” for opening our eyes to the Israeli-Palestinian reality and sparkling our passion on the subject. At a more technical level, the necessary field research for this dissertation would have not been possible without its provision of accommodation during the whole month of June 2019. 1 ABSTRACT Since the occupation of the Arab territories in 1967, Israel has been carrying out policies of de facto annexation, notably through the establishment of settlements and the construction of the Separation Wall. -

Policy Paper and Case Studies Capturing UN Preventive Diplomacy Success: How and Why Does It Work?

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research UN Preventive Diplomacy April 2018 Policy Paper and Case Studies Capturing UN Preventive Diplomacy Success: How and Why Does It Work? Dr. Laurie Nathan Professor of the Practice of Mediation and Director of the Mediation Program, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, University of Notre Dame Adam Day Senior Policy Advisor, United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan João Honwana Former Director in the UN Department of Political Affairs Dr. Rebecca Brubaker Policy Advisor, United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan © 2018 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9077-8 Acknowledgements UNU-CPR is deeply grateful to the Permanent Mission of the United Kingdom to the United Nations for its support to this project. Special thanks go to Thomas Wheeler who was the focal point for both prevention-related projects. UNU-CPR worked in close partnership with the UN Department of Political Affairs throughout this project and benefited greatly from the time and substantive inputs of Teresa Whitfield and Dirk Druet in particular. UNU-CPR would like to thank participants for their contributions to the project’s mid-point peer-review process, including Roxaneh Bazergan, Richard Gowan, Michele Griffin, Marc Jacquand, Asif Khan, Karin Landgren, Ian Martin, Abdel- Fatau Musah, Jake Sherman, and Oliver Ulich. Numerous individuals provided helpful input for and feedback on the country case studies that form the empirical foundation for this project. They are acknowledged in the respective case study chapters in this volume. We are deeply grateful for their support. Finally, we are especially grateful to Emma Hutchinson for her invaluable editorial support to this project. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Preventive Diplomacy and Ethnic Conflict: Possible, Difficult, Necessary

ISSN 1088-2081 Preventive Diplomacy and Ethnic Conflict: Possible, Difficult, Necessary Bruce W. Jentleson University of California, Davis Policy Paper # 27 June 1996 The author and IGCC are grateful to the Pew Charitable Trusts for generous support of this project. Author’s opinions are his own. Copyright © 1996 by the Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation CONTENTS Defining Preventive Diplomacy ........................................................................................5 CONCEPTUAL PARAMETERS FOR A WORKING DEFINITION....................................................6 METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN MEASURING SUCCESS AND FAILURE.....................8 The Possibility of Preventive Diplomacy .........................................................................8 THE PURPOSIVE SOURCES OF ETHNIC CONFLICT ..................................................................8 CASE EVIDENCE OF OPPORTUNITIES MISSED........................................................................9 CASE EVIDENCE OF SUCCESSFUL PREVENTIVE DIPLOMACY ...............................................11 SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................12 Possible, but Difficult.......................................................................................................12 EARLY WARNING................................................................................................................12 POLITICAL WILL .................................................................................................................14