Lessons from Multilateral Envoys GLOBAL PEACE OPERATIONS REVIEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: a Claims Fund Proposal

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham International Law Journal Volume 4, Issue 1 1980 Article 6 Compensation for “Victims” of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: A Claims Fund Proposal R. Scott Garley∗ ∗ Copyright c 1980 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Compensation for “Victims” of Diplomatic Immunity in the United States: A Claims Fund Proposal R. Scott Garley Abstract This Note will briefly trace the development of diplomatic immunity law in the United States, including the changes adopted by the Vienna Convention, leading to the passage of the DRA in 1978. The discussion will then focus upon the DRA and point out a few of the areas in which the statute may fail to provide adequate protection for the rights of private citizens in the United States. As a means of curing the inadequacies of the present DRA, the feasibility of a claims fund designed to compensate the victims of the tortious and criminal acts of foreign diplomats in the United States will be examined. COMPENSATION FOR "VICTIMS" OF DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY IN THE UNITED STATES: A CLAIMS FUND PROPOSAL INTRODUCTION In 1978, Congress passed the Diplomatic Relations Act (DRA)1 which codified the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Rela- tions. 2 The DRA repealed 22 U.S.C. §§ 252-254, the prior United States statute on the subject,3 and established the Vienna Conven- tion as the sole standard to be applied in cases involving the immu- nity of diplomatic personnel4 in the United States. -

TEMPERED LIKE STEEL the Economic Community of West African States Celebrated Its 30Th Anniversary in May, 2005

ECOWAS 30th anniversary and roughly for the same reasons: economic cooperation among of the 15 members have met the economic convergence criteria. member states and collective bargaining strength on a global level. However, it is an instrument whose time has come and it seems cer- Ecowas was an acknowledgement that despite all their differ- tain that the Eco will make its appearance in the near future. ences, the member states were essentially the same in terms of needs, One of Ecowas’ successes has been in allowing relatively free resources and aspirations. It was also an acknowledgement that the movement of people across borders. Passports or national identity integration of their relative small markets into a large regional one documents are still required but not visas. Senegal and Benin issue was essential to accelerate economic activity and therefore growth. Ecowas passports to their citizens. The founders of the organisation were just as convinced that artifi- The Ecowas Secretariat in Abuja is working on modalities to allow cial national barriers, created on old colonial maps, were cutting across document-free movement of people and goods. This might take time, ancient trade routes and patterns and that these barriers had to go. as other regulations, such as residence and establishment rights have However, this came about at a time when sub-regional organisa- to be put in place first. tions were looked on with a degree of suspicion and African coun- One of the organisation's most vital arms is Ecomog, its peace- tries, encouraged by Cold War politics, had become inward-looking keeping force. -

Africa Yearbook

AFRICA YEARBOOK AFRICA YEARBOOK Volume 10 Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2013 EDITED BY ANDREAS MEHLER HENNING MELBER KLAAS VAN WALRAVEN SUB-EDITOR ROLF HOFMEIER LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 ISSN 1871-2525 ISBN 978-90-04-27477-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-28264-3 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents i. Preface ........................................................................................................... vii ii. List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................... ix iii. Factual Overview ........................................................................................... xiii iv. List of Authors ............................................................................................... xvii I. Sub-Saharan Africa (Andreas Mehler, -

Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus

Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus DECEMBER 2011 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Ban Ki-moon (left) is received by Guillaume Soro, Prime Minister of IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many donors, whose Côte d'Ivoire, at Yamoussoukro support makes publications like this one possible. In partic - airport. May 21, 2011. © UN ular, IPI would like to thank the governments of Finland, Photo/Basile Zoma. Norway, and Sweden for their generous contributions to The views expressed in this paper IPI's Coping with Crisis Program. Also, IPI would like to represent those of the authors and thank the Mediation Support Unit of the UN Department of not necessarily those of IPI. IPI Political Affairs for giving it the opportunity to contribute welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit to the process that led up to the Secretary-General's report of a well-informed debate on critical on preventive diplomacy. policies and issues in international affairs. IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor and Senior Fellow Marie O’Reilly, Publications Officer Suggested Citation: Francesco Mancini, ed., “Preventive Diplomacy: Regions in Focus,” New York: International Peace Institute, December 2011. © by International Peace Institute, 2011 All Rights Reserved www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Francesco Mancini Preventive Diplomacy in Africa: Adapting to New Realities . 4 Fabienne Hara Optimizing Preventive-Diplomacy Tools: A Latin American Perspective . 15 Sandra Borda Preventive Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: Redefining the ASEAN Way . 28 Jim Della-Giacoma Preventive Diplomacy on the Korean Peninsula: What Role for the United Nations? . 35 Leon V. -

Allenson 1 Clare Allenson Global Political Economy Honors Capstone Word Count: 8,914 April 14, 2009 the Evolution of Economic I

Allenson 1 Clare Allenson Global Political Economy Honors Capstone Word Count: 8,914 April 14, 2009 The Evolution of Economic Integration in ECOWAS I. Introduction Since gaining political independence in the 1960s, African leaders have consistently reaffirmed their desire to forge mutually beneficial economic and political linkages in order to enhance the social and economic development of Africa’s people. Their desire to achieve greater economic integration of the continent has led to the “‘creation of the most extensive network of regional organizations anywhere in the world 1.’” Regional networks in Africa are not a recent phenomenon, but have an historic roots as the historian Stanislas Adotevi states that “those who deny that Africans have much to trade among themselves ignore the history of precolonial trade, which was based on the exchange of good across different ecological zones, in a dynamic regional trading system centered on the entrepot markets that sprang up at the interstices of these zones 2.” He argues that colonialism disrupted these linkages that could have resulted in commercial centers of regional integration. These historical networks were rekindled in 1975, when fifteen nations, mostly former British and French colonies formed the regional organization, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) with the objective of increasing regional trade, improving free movement of labor, and developing policy harmonization 3. Throughout the 1980s the regional community struggled to create a coherent policy of integration until the early 1990s, when political cooperation increased as a result of a joint 1 Buthelezi, xiv 2 Lavergne, 72 3 Ibid, 133 Allenson 2 regional peacekeeping operation in Liberia and in 1993, member states signed a revised treaty with the goal of accelerating integration. -

General Agreement on Tariffs And

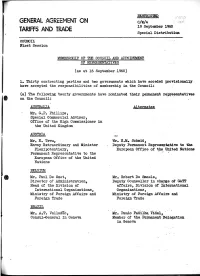

RESTRICTED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON c/wA TARIFFS AND TRADE 19 September 1960 Special Distribution COUNCIL First Session MEMBERSHIP OF THE COUNCIL AND APPOINTMENT OF REPRESENTATIVES (as at 16 September 1960} 1. Thirty contracting parties and two governments which have acceded provisionally have accepted the responsibilities of membership in the Council: (a) The following twenty governments have nominated their permanent representatives on the Council: AUSTRALIA Alternates Mr. G.P. Phillips, Special Commercial Adviser, Office of the High Commissioner in the United Kingdom AUSTRIA ac Mr, E. Treu, Mr. E.M. Schmid. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Deputy Permanent Representative to the Plenipotentiary, European Office of the United Nations Permanent Representative to the European Office of the United Nations BELGIUM Mr. Paul De Smet, Mr. Robert De Smaele, Director of Administration, Deputy Counsellor in charge of GATT Head of the Division of affairs, Division of International International Organizations, Organizations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade Foreign *rade BRAZIL Mr, A.T. Valladao, Mr. Paulo Padilha Vidal, ' Consul-General in Geneva Member of the Permanent Delegation in Geneva C/W/4 Page 2 Alternates CANADA Mr. J.H» Warren, Assistant Deputy Minister, Department of Trade and Commerce CHILE H.E. Mr. F. Garcia Oldini, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary in Switzerland CUBA H.E. Dr. E. Camejo-Argudin, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Head of the Permanent Mission to the inter national organizations in Geneva CZECHOSLDVAKIA Dr. Otto Benes, Economic Counsellor, Permanent Mission to the European Office of the United Nations DENMARK ecu Mr. N»V. Skak-Nielsen, Minister Plenipotentiary, Permanent Representative to the international organizations in Geneva FINLAND Mr. -

Legation, Mmebre M .J Woulbruon (Belgique), De La Délégation Per- Manneet Belge Auprès Del' ONU Membre M

UNRESTRICTED INTERIM COMMISSION COMMISSION INTERIMAIRE DE ICITO/EC. 2/INF.2 FOR THE INTERNATIONAL L'ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE 25 August 1948 TRADE ORGANIZATION DU COMMERCE ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Executive Committee Comité Exécutif Second Session Deuxiéme Session LIST OF DELEGATES - LISTE DES DELEGUES Mr. J. A Tonkin, Leader Mr. J. Fletcher Mr. J. Russell Mr. c.L. S. Hewitt Mr.G. Warwick Smith Miss Judith Bearup, Stenographer Miss N. C. Stack, Stenographer Miss Mary Heffer, Stenographer Benelux M. Max Suetens, Ministre Plénipotentiaire et Envoyé Extraordinaire , Président D.r .A. .B Speekenbrink,Directeur Général du Commerce Extérieur, Vice-President Male Professeur .E Devries (territoires néerlandais d'outre-mer), Mmebre M.G. Cassiers (Belgique), Premier Secrétaire de Legation, Mmebre M .J Woulbruon (Belgique), de la Délégation per- manneet belge auprès del' ONU Membre M. Indekeu (Belgique), Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, , Adviser Dr. G. A. L amsvelt, (Netherlands) , Adviser Dr. J. Boehstal, (Netherlands), Secretary Brazil Ambassador Joao Muniz, Chief Delegate Eduardo Lopes Rodrigues, Delegate M. Roberto de Oliveira Campos, Adviser M. Oswaldo Behn Franco, Secretary Miss Maria Ilvà Pinto Ayres, Stenographer Miss Maria José Argollo, Stenographer Canada Hon. L.D. Wilgress, Canadian Ambassador to Switzerland, Chairman Mr. L.E. Couillard, Departrnent of Trade and Commerce Mr. S.S. Reisman, Department of Finance Miss Marion Henson, Secretary to Mr. Wilgress China Dr. Wunsz King, Leader Mr. Chi Chu, Delegate Mr. H.S. Hsu, Adviser Mr. S.M. Kao, Adviser Mr. C.L.. Pang, Secretary Miss Gloria Rosen, Stenographer Colombia Dr. Alfonso Bonilla Gutierrez, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, Senator of the Republic Dr. Camilo de Brigard Silva, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary Dr. -

2013-05 Ali Gazibo

ECOLE DOCTORALE DE SCIENCE POLITIQUE DE PARIS UNIVERSITÉ PARIS1 PANTHÉON-SORBONNE La régionalisation de la paix et de la sécurité internationales post-guerre froide dans le cadre de la CEDEAO : la construction d’un ordre sécuritaire régional, entre autonomie et interdépendance. Thèse pour le doctorat en science politique GAZIBO Kadidiatou Sous la direction de Monsieur Yves VILTARD Membres du Jury : M. Viltard Yves. Directeur de Recherches, Maitre de conférences, Université Paris1. M. Lindemann Thomas. Professeur des Universités, Université d’Artois. Rapporteur. M. Tidjani Alou Mahaman. Doyen de la Faculté de Droit et des Sciences économiques, Université Abdou Moumouni du Niger, Rapporteur. Mme Siméant Johanna. Professeure des Universités, Université Paris1. 22 mai 2013 1 Remerciements Aux termes de ces années de recherche, mes pensées vont d’abord naturellement vers feu le professeur François Gresle, qui avait bien voulu accepter de diriger en premier cette thèse mais que des circonstances douloureuses n’ont pas permis de voir la fin. Je lui témoigne ici toute ma reconnaissance. Ensuite, je remercie particulièrement Monsieur Yves Viltard qui, en dépit de ses nombreuses occupations, a bien voulu accepter de pendre part à mi-parcours à cette aventure, en dirigeant et s’intéressant à cette étude. Qu’il trouve ici l’expression de ma profonde gratitude. Enfin, je tiens également à remercier mon oncle que j’aime, le professeur Mamoudou Gazibo pour sa patience et ses conseils sur le plan de la méthodologie et ses remarques fructueuses et sans lequel cette thèse n’aurait pas vu le jour . Il en va de même pour mon père Gazibo Ali, mon frère Gazibo Moussa, mes sœurs Gazibo Fatoumata et Gazibo Rakiatou et la grande famille Gazibo qui ont été là pour me soutenir, qu’ils trouvent ici l’expression de mon profond amour. -

Economic Community of Communnaute Economique

ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF COMMUNAUTE ECONOMIQUE WEST AFRICAN STATES DES ETATS DE L’AFRIQUE DE L’OUEST Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Washington, D.C., October 19, 2007 Lecture On “The Role of the Economic Community of West African States in Achieving the Economic Integration of West Africa” By H.E. Dr. Mohamed Ibn Chambas President, ECOWAS Commission I. INTRODUCTION Director of the Wilson Center, Esteemed Scholars, Researchers, Fellows and Students of Woodrow Wilson Center, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, President Woodrow Wilson was a remarkable President of the United States whose internalisation was to set a high benchmark for multilateral diplomacy. As an accomplished scholar, Woodrow Wilson emphasized policy-oriented research and saw academia in a mutually reinforcing partnership with policy making in the common enterprise to forge a government that delivers “justice, liberty and peace”. As a President, he was a champion of national reconciliation whose anti-corruption and anti-trust crusade in favour of the poor made this country more just and caring. A thorough pacifist and renowned world statesman, his reluctant entry into World War I had one goal – to end the war and launch world peace based on collective security, a task he brilliantly accomplished. I therefore feel humbled, greatly honoured and privileged to be at this famous Center, a living reminder and symbol of the ideals that Woodrow Wilson stood for, to share my thoughts Lecture by H.E. Dr. Mohamed Ibn Chambas 1 President of the ECOWAS Commission At the Woodrow Wilson Center for Scholars with you on the role of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in achieving the economic integration of West Africa. -

Security Council Provisional Seventy-Second Year

United Nations S/ PV.8002 Security Council Provisional Seventy-second year 8002nd meeting Thursday, 13 July 2017, 11.05 a.m. New York President: Mr. Wu Haitao ................................. (China) Members: Bolivia (Plurinational State of) ..................... Mr. Llorentty Solíz Egypt ......................................... Mr. Moustafa Ethiopia ....................................... Mr. Alemu France ........................................ Mr. Michon Italy .......................................... Mr. Cardi Japan ......................................... Mr. Kawamura Kazakhstan .................................... Mr. Umarov Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Iliichev Senegal ....................................... Mr. Seck Sweden ....................................... Mr. Vaverka Ukraine ....................................... Mr. Yelchen ko United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Mr. Hickey United States of America .......................... Ms. Sison Uruguay ....................................... Mr. Bermúdez Agenda Peace consolidation in West Africa Report of the Secretary-General on the activities of the United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (S/2017/563) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record -

De Facto and De Jure Annexation: a Relevant Distinction in International Law? Israel and Area C: a Case Study

FREE UNIVERSITY OF BRUSSELS European Master’s Degree in Human Rights and Democratisation A.Y. 2018/2019 De facto and de jure annexation: a relevant distinction in International Law? Israel and Area C: a case study Author: Eugenia de Lacalle Supervisor: François Dubuisson ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, our warmest thanks go to our thesis supervisor, François Dubuisson. A big part of this piece of work is the fruit of his advice and vast knowledge on both the conflict and International Law, and we certainly would not have been able to carry it out without his help. It has been an amazing experience to work with him, and we have learned more through having conversations with him than by spending hours doing research. We would like to deeply thank as well all those experts and professors that received an e-mail from a stranger and accepted to share their time, knowledge and opinions on such a controversial topic. They have provided a big part of the foundation of this research, all the while contributing to shape our perspectives and deepen our insight of the conflict. A list of these outstanding professionals can be found in Annex 1. Finally, we would also like to thank the Spanish NGO “Youth, Wake-Up!” for opening our eyes to the Israeli-Palestinian reality and sparkling our passion on the subject. At a more technical level, the necessary field research for this dissertation would have not been possible without its provision of accommodation during the whole month of June 2019. 1 ABSTRACT Since the occupation of the Arab territories in 1967, Israel has been carrying out policies of de facto annexation, notably through the establishment of settlements and the construction of the Separation Wall. -

American Diplomacy at Risk

American Diplomacy at Risk APRIL 2015 American Academy of Diplomacy April 2015 | 1 American Academy of Diplomacy American Diplomacy at Risk APRIL 2015 © Copyright 2015 American Academy of Diplomacy 1200 18th Street NW, Suite 902 Washington DC 20036 202.331.3721 www.academyofdiplomacy.org Contents Participants . 6 Donors . 7 I . Introduction: American Diplomacy at Risk . 9 II . The Politicization of American Diplomacy . 14 A. General Discussion . 14 B. The Cost of Non-Career Political Appointees . .15 C. Recommendations . 17 III . The Nullification of the Foreign Service Act of 1980 . .22 . A. General Discussion . 22 B. Recommendations . 24 IV . Valuing the Professional Career Foreign Service . .30 A. Basic Skills of Diplomacy . 30 B. Diplomatic Readiness Compromised . 31 C. Background . 34 D. Entry-Level Recommendations . 39 E. Mid-Level Recommendations . 42 V . Defining and Improving Opportunities for Professional Civil Service Employees 44 A. Discussion . 44 B. Recommendations . 45 VI . State’s Workforce Development, Organization and Management . .47 A. Discussion . 47 B. Recommendations . 47 Appendix A . 51 Washington Post op-ed by Susan R. Johnson, Ronald E. Neumann and Thomas R. Pickering of April 11, 2013 Appendix B . 53 State Press Guidance of April 12, 2013 Appendix C . 55 List of Special Advisors, Envoys and Representatives Appendix D . 57 Project Paper: Study of Entry-Level Officers, The Foreign Service Professionalism Project for the American Academy of Diplomacy, by Jack Zetkulic, July 9, 2014 American Diplomacy at Risk Participants Project Team Ambassador Thomas D. Boyatt, Susan Johnson, Ambassador Lange Schermerhorn, Ambassador Clyde Taylor Co-Chairs Ambassador Marc Grossman and Ambassador Thomas R. Pickering Chair of Red Team Ambassador Edward Rowell American Academy of Diplomacy Support Team President: Ambassador Ronald E.