Hospitality Management Graduate Certification And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD APPLICATION STATISTICS BY INTITUTION AND GENDER (AGE LESS THAN 16) S/NO INSTITUTION F M TOTAL 1 ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE 78 89 167 2 ACHIEVERS UNIVERSITY, OWO, ONDO STATE 3 0 3 3 ADAMAWA STATE UNIVERSITY, MUBI, ADAMAWA STATE 8 5 13 4 ADEKUNLE AJASIN UNIVERSITY, AKUNGBA-AKOKO, ONDO STATE 169 68 237 5 ADELEKE UNIVERSITY, EDE, OSUN STATE 6 4 10 6 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO STATE. (AFFL TO OAU, ILE-IFE) 8 4 12 7 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO, ONDO STATE 1 0 1 8 AFE BABALOLA UNIVERSITY, ADO-EKITI, EKITI STATE 92 71 163 9 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY TEACHING HOSPITAL, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 2 0 2 10 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 826 483 1309 11 AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, KADUNA, KADUNA STATE 2 1 3 12 AJAYI CROWTHER UNIVERSITY, OYO, OYO STATE 6 1 7 13 AKANU IBIAM FEDERAL POLYTECHNIC, UNWANA, AFIKPO, EBONYI STATE 5 3 8 14 AKWA IBOM STATE UNIVERSITY, IKOT-AKPADEN, AKWA IBOM STATE 39 28 67 15 AKWA-IBOM STATE POLYTECHNIC, IKOT-OSURUA, AKWA IBOM STATE 7 3 10 16 ALEX EKWUEME FEDERAL UNIVERSITY, NDUFU-ALIKE, EBONYI STATE 55 33 88 17 AL-HIKMAH UNIVERSITY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE 3 1 4 18 AL-QALAM UNIVERSITY, KATSINA, KATSINA STATE 6 1 7 19 ALVAN IKOKU COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, IMO STATE, (AFFL TO UNIV OF NIGERA, NSUKKA) 3 1 4 20 AMBROSE ALLI UNIVERSITY, EKPOMA, EDO STATE 208 117 325 21 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, YOLA, ADAMAWA STATE 4 8 12 22 AMINU DABO COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KANO, KANO STATE 1 0 1 23 ANCHOR UNIVERSITY, AYOBO, LAGOS STATE -

Promoting Integrated Water Resources Management in South West Nigeria: the Need for Collaboration and Partnershippartnership

Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) Vol. 34 No. 2, April 2015, pp. 414 – 420 Copyright© Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, ISSN: 1115-8443 www.nijotech.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v34i2 .28 PROMOTING INTEGRATED WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN SOUTH WEST NIGERIA: THE NEED FOR COLLABORATION AND PARTNERSHIPPARTNERSHIP A. Sobowale 1*1*1* , J., J. K. Adewumi 222 and O. A. Bamgboye 333 111,1,,, 222 SOUTH WEST REGIONAL CENTRE FOR NATIONAL WATER RESOURCES CAPACITY BUILDING NETWORK , FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE , PMB 2240, ABEOKUTA 110001, NIGERIA. 333 NATIONAL WATER RESOURCES INSTITUTE , PMB 2309, KADUNA , NIGERIA. EEE-E---mailmail AddressAddresseseseses:: 1 [email protected], 222 [email protected] 333 [email protected] ABSTRACT ThisThisThis paper eelucidateslucidates the need to implement Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) in SSSouthSouth WWWestWest NigeriaNigeria.. At present, water related programmes in existing capacity building institutions ((CBIsCBIsCBIsCBIs)))) do not have IWRM and climate change adaptation in their synopsis; ttthisthis suggests tthehe need for curriculum review. Another observation was that many of the professionals in the water sectorsector organizations ((WSOsWSOsWSOs)))) are aging with none of these organizations having succession plansplans.. D. DevelopD evelopevelopinging and implementing succession plans require collaboration and partnership with CBIs in the regionregion;;;; ttthethehehe recent establishment of the National Water Resources CapacityCapacity Building NetwNetwNetworkNetw ork (NWRCBNet) in the country is timelytimely;;;; itititwillit will provide a platform for IWRM implementation and capacity building in the water sectorsector.... The south west regional center at the Federal UniveUniversityrsity of Agriculture, Abeokuta has been spear heading this vision and the results achieved so far in the south west region has been encouragingencouraging... -

Organizational Effectiveness in Higher Education: a Case Study of Selected Polytechnics in Nigeria

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF SOCIAL AND HUMAN SCIENCES SOUTHAMPTON EDUCATION SCHOOL Organizational Effectiveness in Higher Education: A Case Study of Selected Polytechnics in Nigeria by Oluwole Adeniyi Solanke Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy APRIL 2014 1 ABSTRACT This study compares perceived organisational effectiveness within polytechnic higher education in Nigeria. A qualitative methodology and an exploratory case study (Yin, 2003) enable an in-depth understanding of the term effectiveness as it affects polytechnic education in Nigeria. A comparative theoretical framework is applied, examining three polytechnic institutions representing Federal, State and Private structures under a variety of conditions. Data was based on triangulation comprising fifty-two (52) semi-structured interviews, one focus group, and documentary evidence. The participants in the study were the dominant coalition in the institutions comprising top- academic leaders, lecturers, non-academic staff, and students. -

Poly Enrolment Summary by Institution

POLYTECHNIC ENROLMENT SUMMARY BY INSTITUTIONS: 2011/2012 Pre-ND ND 1 ND 2 ND 3 HND 1 HND 2 HND 3 Total S/No Institution Location M F M F M F M F M F M F M F M F MF 1 Abdu Gusau Polytechnic Talata Mafara Zamfara 90 30 459 152 478 117 0 0 270 51 261 46 0 0 1558 396 1954 2 Abia State Polytechnic Aba Abia 0 0 390 346 378 358 0 0 382 404 303 357 0 0 1453 1465 2918 3 Abraham Adesanya Polytechnic, Ijebu Igbo Ogun 0 0 175 180 208 198 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 383 378 761 4 Abubakar Tatari Ali Polytechnic Bauchi Bauchi 0 0 846 361 625 209 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1471 570 2041 5 Adamawa State Polytechnic Yola Adamawa 0 0 136 37 121 34 0 0 5 2 7 1 0 0 269 74 343 6 Akanu Ibiam Federal Polytechnic Unwana, Afikpo Ebonyi 36 36 1174 885 825 634 0 0 870 522 607 373 0 0 3512 2450 5962 7 Akwa Ibom State College of Arts and Science, Nung Ukim Akwa Ibom 24 12 98 75 88 75 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 210 162 372 8 Akwa Ibom State Polytechnic Ikot Osurua Akwa Ibom 0 0 378 393 386 295 0 0 227 348 164 280 0 0 1155 1316 2471 9 Allover Central Polytechnic Otta Ogun 0 0 68 66 88 72 0 0 50 43 59 51 0 0 265 232 497 10 Auchi Polytechnic Auchi Edo 0 0 3075 2160 2427 1844 0 0 1857 1593 1869 1529 0 0 9228 7126 16354 11 Benue State Polytechnic Ugbokolo Benue 152 39 382 148 293 103 0 0 353 146 273 107 0 0 1453 543 1996 12 Covenant Polytechnic, Aba Abia 0 0 100 89 105 49 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 205 138 343 13 Crown Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti Ekiti 0 0 145 128 148 116 0 0 68 39 48 54 0 0 409 337 746 14 D.S. -

Sept to Dec 2018 Bulletin 2

September - December, 2018 Vol. 4 No. 12 ISSN NO:2141-9590 Snippets on NBTE National Assembly Education Board Chairman Prof. Modupe Adelabu Committees on Oversight Visits to NBTE Executive Secretary Dr. Masa'udu A. Kazaure, mni he Senate Committee NBTE Vision and Mission on Tertiary Vision Education & To be a world class regulatory body TE T F u n d a n d i t s for the promotion of Technical and Vocational Education and Training counterpart, House of in Nigeria R e p r e s e n t a t i v e s Mission Committee on Tertiary To promote the production of skilled Education & Services technical and professional manpower for the development and were at the National sustenance of the national economy Board for Technical Education (NBTE) in Sen. Barau Jibril, Chairman Hon. Aminu Suleiman, Chairman Core Mandate Senate Committee on Tertiary House Committee on Tertiary To coordinate all aspects of Kaduna on separate Education and TETFund Education and Services Technical and Vocational Education visits to carry out their falling outside university education statutory oversight NBTE Statutes function at the Board. · NBTE enabling Act No. 9 of 11th January, 1977 T h e H o u s e o f Representatives team · Education (National Minimum which visited the Board Standard and Establishment of th Institution Act No. 16 of August on 5 November, 2018 1985 w a s l e d b y t h e and Act No. 9 of 1993 Committee's Chairman, No. of Institutions under NBTE R t . H o n o u r a b l e Purview §Polytechnics 123 S u l e i m a n A m i n u . -

Lagos State Poctket Factfinder

HISTORY Before the creation of the States in 1967, the identity of Lagos was restricted to the Lagos Island of Eko (Bini word for war camp). The first settlers in Eko were the Aworis, who were mostly hunters and fishermen. They had migrated from Ile-Ife by stages to the coast at Ebute- Metta. The Aworis were later reinforced by a band of Benin warriors and joined by other Yoruba elements who settled on the mainland for a while till the danger of an attack by the warring tribes plaguing Yorubaland drove them to seek the security of the nearest island, Iddo, from where they spread to Eko. By 1851 after the abolition of the slave trade, there was a great attraction to Lagos by the repatriates. First were the Saro, mainly freed Yoruba captives and their descendants who, having been set ashore in Sierra Leone, responded to the pull of their homeland, and returned in successive waves to Lagos. Having had the privilege of Western education and christianity, they made remarkable contributions to education and the rapid modernisation of Lagos. They were granted land to settle in the Olowogbowo and Breadfruit areas of the island. The Brazilian returnees, the Aguda, also started arriving in Lagos in the mid-19th century and brought with them the skills they had acquired in Brazil. Most of them were master-builders, carpenters and masons, and gave the distinct charaterisitics of Brazilian architecture to their residential buildings at Bamgbose and Campos Square areas which form a large proportion of architectural richness of the city. -

An Assessment of Open Educational Resources by Students in Selected Academic Institutions in Southwest, Nigeria

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 2020 An Assessment of Open Educational Resources by students in selected Academic Institutions in Southwest, Nigeria NJEZE MIRACLE [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons MIRACLE, NJEZE, "An Assessment of Open Educational Resources by students in selected Academic Institutions in Southwest, Nigeria" (2020). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 4356. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4356 An Assessment of Open Educational Resources by students in selected Academic Institutions in Southwest, Nigeria National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) Centre for Resource Learning (Library) Abeokuta Study Centre Opposite NNPC, Oke Mosan Abeokuta, Ogun State Nigeria [email protected] +234 0803 592 1524 1 Abstract This paper examined assessment of Open Educational Resources (OER) by students in selected Academic Institutions in Southwest Nigeria. A descriptive research design was used for this study and the instrument used for data collection was the questionnaire. The population of this study comprised two hundred and fifty two respondents from selected academic institutions and a stratified sampling technique was used to select respondents from each of the nine institutions investigated. This study assessed the use of Open Educational Resources by students in nine academic institutions in Nigeria which comprised (Federal, State and Private Universities; Polytechnics; and Colleges of Education) in Nigeria. Findings illustrates that 40.5% of students do not use OER because they are not aware of OER. Male students use more OER than females. -

15Th Edition 2010 Directory of Accredited TVET Institutions In

DIRECTORY OF ACCREDITED PROGRAMMES OFFERED IN POLYTECHNICS AND SIMILAR TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS 15th EDITION JANUARY, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Cover page Table of Contents i Foreword vi Key to Abbreviations vii List of Polytechnics in Nigeria with years of Establishment and Ownership viii List of Colleges of Agriculture with years of Establishment and Ownership xiii List of Colleges of Health Science with years of Establishment and Ownership xv List of Other Specialised Institutions xvi List of Innovation Enterprises Institutions (IEIs) xvii Polytechnics and other similar Institutions with Accredited Programmes in the Six Geo-political Zones xxiii List of Programmes Available in Nigerian Polytechnics and Similar Institutions xxviii List of Programmes in IEIs xxxi Citation xxxii Polytechnics Offering Accredited Programmes Abdu Gusau Polytechnic, Talata Mafara 1 Abia State Polytechnic, Aba 1 Abraham Adesenya Polytechnic, Ijebu Igbo 2 Abubakar Tatari Ali Polytechnic, Bauchi 2 Adamawa State Polytechnic, Yola 3 Akanu Ibiam Federal Polytechnic, Unwana 3 Akwa Ibom State College of Art & Science, Nung Ukim 4 Akwa Ibom State Polytechnic, Ikot Osurua 4 Allover Central Polytechnic, Sango Ota 5 Auchi Polytechnic, Auchi 6 Benue State Polytechnic, Ugbokolo 7 Crown Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti 8 Delta State Polytechnic, Ogwashi-Uku 9 Delta State Polytechnic, Otefe-Oghara 9 Delta State Polytechnic, Ozoro 10 Dorben Polytechnic, Bwari 11 Edo State Institute of Technology and Management, Usen 11 Federal Polytechnic, Ado – Ekiti 11 Federal Polytechnic, Bauchi -

The Status and Challenges of Mass Communication Education in Nigeria

International Journal of Research in Arts and Social Sciences Vol 5 The Status And Challenges Of Mass Communication Education In Nigeria Nnanyelugo Okoro Paul Martin Obayi Alexander Chima Onyebuchi Abstract This study examines journalism training and mass communication education in Nigeria with the aim of pointing out the challenges that need to be addressed in order to improve on the quality of communication training and practice in the country. It argued that ever since the University of Nigeria, Nsukka pioneered journalism in 1961 at the Bachelor of Arts (B.A) degree level, journalism and mass communication education in Nigeria have witness tremendous recognition in terms of the number of institutions and institutes that now run mass communication and journalism training programmes in the country. The study noted, however, that the state of journalism education in Nigeria is in dilemma as a result of certain problems that have besieged both the profession and its training institutions. The study concluded that there is need for the revitalisation of journalism training and mass communication education at all levels in the country in order to raise the profession to world standard. Key words: Journalism training and mass communication education Introduction Over the years, scholars have argued that journalism and mass communication education in Nigeria needs serious attention in order to meet up with the developments in journalism practice all over the world. Harping on this issue, Akinfeleye (2009) noted that “it has now become a truism that a low degree of literacy rate contributes to a low degree of Journalism Education and training, while on the other hand, a high level of literacy tends to contribute to a higher degree of journalistic training and professional standards”. -

List of Schools

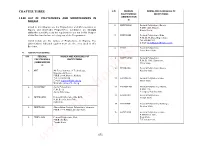

CHAPTER THREE S/N FEDERAL NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF POLYTECHNICS INSTITUTIONS (ABBREVIATION 3.0.00 LIST OF POLYTECHNICS AND MONOTECHNICS IN S) NIGERIA 6. FEDPO-BAU Federal Polytechnic, Bauchi, Listed in this Chapter are the Polytechnics and Monotechnics in P.M.B. 0231, Bauchi, Nigeria and obtainable Programmes. Candidates are strongly Bauchi State. advised to carefully study the requirements set out in this Chapter of this Brochure before selecting any of the Programmes. 7. FEDPO-BID Federal Polytechnic, Bida, P. M. B. 55, Bida, Niger State. Listed below are the names of Polytechnics in Nigeria. The Tel: 066-461707 E-mail: [email protected] abbreviations indicated against them are the ones used in this Brochure. 8. FP-CR Federalo Polytechnic, Cross River State A. FEDERAL POLYTECHNICS c S/N FEDERAL NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF . 9. FEDPO-DAM Federal Polytechnic, POLYTECHNICS INSTITUTIONS t P. M. B. 1006, Damaturu, (ABBREVIATION Yobe State. S) s 10. FP-DAURAi Federal Polytechnic, Daura, 1. AFIT Air Force Institute of Technology, Katsina State Nigerian Air Force, g P.M.B. 2104, Mando, Kaduna l Tel: 07029306014 11. FEDPO-EDE Federal Polytechnic, Ede, E-mail: [email protected] Osun State Web Site: www.afit.edu.ng o 2. AUCHIPOLY Auchi Polytechnic, 12. FEDPO-EKO Federal Polytechnic, Ekowe, P. M. B. 13, o P.M.B. 110, Auchi, Edo State. Yenagoa, Bayelsa State h 13. FP-ENUGU Federal Polytechnic, 3. FEDPO-ADO Federal Polytechnic, Ado-Ekiti, Enugu State P. M. B. 5351, Ado-Ekiti, c Ekiti State. 14. FP-GOMBE Federal Polytechnic, Kaltungo, s Gombe State 4. -

Ican Accreditated Tertiary Institutions Updated on May 28, 2020

THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF NIGERIA ICAN ACCREDITATED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS UPDATED ON MAY 28, 2020. Note: Students who graduated after the sessions covered in the accreditation from the Institutions highlighted in ‘RED’ will no longer enjoy exemption benefits until the accreditation is revalidated UNIVERSITIES New due Year of first Sessions covered session for re- S/N Name of Institution accreditation in accreditation Remark accreditation 1 Abia State University, Uturu 1987 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 2 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 2016/2017 3 Achievers University , Owo, Ondo State 2010 2015/2016 To 2018/2019 2019/2020 4 Adamawa State University, Mubi Adamawa State 2008 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 5 Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State 2007 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 6 Adeleke University, Ede, Osun State 2017 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 7 Afe Babalola University ,Ado- Ekiti 2013 2016/2017 To 2019/2020 2020/2021 8 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State 1974 2018/2019 To 2021/2022 2022/2023 9 Ajayi Crowther University,Oyo State 2009 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 10 AL-Hikman University , Ilorin, Kwara State 2009 2012/2013 To 2015/2016 2016/2017 11 Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State 1994 2017/2018 To 2020/2021 2021/2022 12 American University Of Nigeria, Yola Adamawa State 2008 2014/2015 To 2017/2018 2018/2019 13 Babcock University, Ilishan, Ogun State 2003 2009/2010 T0 2012/2013 Under MCATI 14 Bayero University, Kano State -

S/N Institution Name Female

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD 2015 ADMISSION STATISTICS BY INSTITUTION AND GENDER (CANDIDATES BELOW 16) S/N INSTITUTION NAME FEMALE MALE TOTAL 1 Abdul-Gusau Polytechnic Talata-Mafara 1 2 3 2 Abia State College Of Education (Technical) 2 0 2 3 Abia State College Of Health Sciences And Management Technology Aba 8 6 14 4 Abia State Polytechnic Aba 14 14 28 5 Abia State University Uturu. 255 109 364 6 Abraham Adesanya Polytechnic Ijebu-Igbo Ogun State 14 4 18 7 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Bauchi 33 56 89 8 Abubakar Tatari Ali Polytechnic Bauchi 5 8 13 9 Achievers University Owo 38 10 48 10 Adamawa State Poly Yola 7 5 12 11 Adamawa State University Mubi 18 14 32 12 Adekunle Ajasin University Akungba-Akoko 181 105 286 13 Adeleke University Ede Osun State 58 56 114 14 Adeniran Ogunsanya College Of Education Otto/Ijanikin 45 17 62 15 Adeniran Ogunsanya College Of Education Otto/Ijanikin Lagos (Affliated To Ekit 22 11 33 16 Adeyemi College Of Education (Affliated To Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife 41 27 68 17 Adeyemi College Of Education Ondo 138 58 196 18 Afe Babalola University Ado-Ekiti 327 231 558 19 Afrihub Ict Institute Abuja 1 1 2 20 Ahmadu Bello University Zaria 275 194 469 21 Air Force Institute Of Technology Nigerian Air Force Kaduna 0 4 4 22 Ajayi Crowther University Oyo 83 56 139 23 Akanu Ibiam Federal Polytechnic Unwana Afikpo 8 8 16 24 Akperan Orshi College Of Agriculture Yandev 3 8 11 25 Akwa Ibom State University Ikot-Akpaden 75 57 132 26 Akwa-Ibom State College Of Education Afaha-Nsit 38 9 47 27 Akwa-Ibom State Polytechnic Ikot-Osurua 4 12 16 28 Al- Hikmah University Ilorin 49 20 69 29 Al-Qalam University Katsina 10 5 15 30 Alvan Ikoku College Of Educ.