Diagnosing Organic Causes of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: Findings from a One-Year Cohort of the Freiburg Diagnostic Protocol in Psychosis (FDPP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotyping in Psychiatry

CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotyping in psychiatry Citation for published version (APA): Koopmans, A. B. (2021). CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotyping in psychiatry: bridging the gap between practice and lab. ProefschriftMaken. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20210512ak Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2021 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20210512ak Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

Drugs for the Treatment of Hypercalcaemia C. R. PATERSON

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.50.581.158 on 1 March 1974. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (March 1974) 50, 158-162. Drugs for the treatment of hypercalcaemia C. R. PATERSON M.A., D.M., M.R.C.PATH. Department of Clinical Chemistry, University of Dundee, Dundee Summary able commercially (Phosphate Sandoz). The initial Hypercalcaemia is ordinarily treated by treatment of dose is 1-3 g (of phosphorus) per day according to the underlying disorder. In some cases, as in malignant the size of the patient. The serum calcium should be disease, in vitamin D poisoning and after a failed checked daily at first and the dose adjusted appro- parathyroidectomy, the hypercalcaemia itself needs to priately so that the maintenace dose is the minimum be treated. A large number of methods have been consistent with control of the serum calcium. Oral advocated for this, but phosphate is the drug of choice phosphate therapy is effective in the management of in most patients. This paper outlines its use, mode of hypercalcaemia of malignant disease and myeloma action and side effects and reviews the other methods (Goldsmith and Ingbar, 1966; Goldsmith et al., proposed for the management of hypercalcaemia. 1968; Thalassinos and Joplin, 1968), in hyperpara- thyroidism (Dent, 1962; Goldsmith and Ingbar, 1966; Eisenberg, 1968), and in vitamin D poisoningProtected by copyright. Introduction (Goldsmith and Ingbar, 1966). The management of hypercalcaemia is ordinarily Intravenous phosphate therapy is used in the that of the underlying disorder (Wills, 1971; management of acute hypercalcaemia, especially in Henrard, 1971; Watson, 1972). There are, however, the patient who is vomiting or in coma. -

A Case of Cushing Syndrome with Both Secondary Hypothyroidism and Hypercalcemia Due to Postoperative Adrenal Insufficiency

Endocrine Journal 2004, 51 (1), 105–113 NOTE A Case of Cushing Syndrome with Both Secondary Hypothyroidism and Hypercalcemia Due to Postoperative Adrenal Insufficiency MASAHITO KATAHIRA, TSUTOMU YAMADA* AND MASAHIKO KAWAI* Department of Internal Medicine, Kyoritsu General Hospital, Nagoya 456-8611, Japan *Division of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Okazaki City Hospital, Okazaki 444-8553, Japan Abstract. A 48-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because of secondary hypothyroidism. Upon admission a left adrenal tumor was also detected using computed tomography. Laboratory data and adrenal scintigraphy were compatible with Cushing syndrome due to the left adrenocortical adenoma, although she showed no response to the TRH stimulation test. Hypercortisolism resulting in secondary hypothyroidism was diagnosed. After a left adrenalectomy, hydrocortisone administration was begun and the dose was reduced gradually. After discharge on the 23rd postoperative day, she began to suffer from anorexia. ACTH level remained low, and serum cortisol, free thyroxine and TSH levels were within the normal range. Since her condition became worse, she was re-admitted on the 107th postoperative day at which time serum calcium level was high (15.6 mg/dl). Both ACTH response to the CRH stimulation test and TSH response to the TRH stimulation test were restored to almost normal levels, but there was no response of cortisol to CRH stimulation test. We diagnosed that the hypercalcemia was due to adrenal insufficiency. Although the serum calcium level decreased to normal after hydrocortisone was increased (35 mg/day), secondary hypothyroidism recurred. It was suggested that sufficient glucocorticoids suppressed TSH secretion mainly at the pituitary level, which resulted in secondary (corticogenic) hypothyroidism. -

PARANEOPLASTIC SYNDROMES: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: First Published As 10.1136/Jnnp.2004.040378 on 14 May 2004

PARANEOPLASTIC SYNDROMES: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.2004.040378 on 14 May 2004. Downloaded from WHEN TO SUSPECT, HOW TO CONFIRM, AND HOW TO MANAGE ii43 J H Rees J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75(Suppl II):ii43–ii50. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.040378 eurological manifestations of cancer are common, disabling, and often multifactorial (table 1). The concept that malignant disease can cause damage to the nervous system Nabove and beyond that caused by direct or metastatic infiltration is familiar to all clinicians looking after cancer patients. These ‘‘remote effects’’ or paraneoplastic manifestations of cancer include metabolic and endocrine syndromes such as hypercalcaemia, and the syndrome of inappropriate ADH (antidiuretic hormone) secretion. Paraneoplastic neurological disorders (PNDs) are remote effects of systemic malignancies that affect the nervous system. The term PND is reserved for those disorders that are caused by an autoimmune response directed against antigens common to the tumour and nerve cells. PNDs are much less common than direct, metastatic, and treatment related complications of cancer, but are nevertheless important because they cause severe neurological morbidity and mortality and frequently present to the neurologist in a patient without a known malignancy. Because of the relative rarity of PND, neurological dysfunction should only be regarded as paraneoplastic if a particular neoplasm associates with a remote but specific effect on the nervous system more frequently than would be expected by chance. For example, subacute cerebellar ataxia in the setting of ovarian cancer is sufficiently characteristic to be called paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration, as long as other causes have been ruled out. -

GAF Timberline Series Application Instructions

Application Instructions Timberline® HDTM, Timberline® Natural ShadowTM, Timberline® Ultra HDTM, Timberline® Cool Series, Timberline® American HarvestTM, Updated: 4/12 Quality You Can Trust… From North America’s Largest Roofing Manufacturer!™ www.gaf.com Quality You Can Trust…From North America’s Largest Roofing Manufacturer!™ ¡Calidad En La Que Usted Puede Confiar...Del Fabricante De Techos Más Grande De Norteamérica!™ Une Qualité À Laquelle Vous Pouvez Vous Fier... Du Plus Gros Fabricant De Toitures En Amérique Du Nord! MC INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS · INSTRUCCIONES DE INSTALACIÓN · INSTRUCTIONS D’INSTALLATION LIFETIME HIGH DEFINITION® SHINGLES LIFETIME SHINGLES TEJAS DE ALTA DEFINICIÓN® DE POR VIDA TEJAS DE POR VIDA BARDEAUX DE HAUTE DÉFINITION® À VIE BARDEAUX À VIE LIFETIME HIGH DEFINITION® SHINGLES TEJAS DE ALTA DEFINICIÓN® DE POR VIDA ENERGY-SAVING ARCHITECTURAL SHINGLES TEJAS ARQUITECTÓNICAS PARA AHORRO DE ENERGÍA BARDEAUX DE HAUTE DÉFINITION® À VIE BARDEAUX ARCHITECTURAUX ÉCONERGÉTIQUES GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS t."5&3*"-4"'&5:%"5"4)&&54 When using GAF products, e.g., shingles, underlayments, plastic cement, etc., please refer to the applicable MSDS. The most current versions are available at www.gaf.com. GAF does not provide safety data sheets or installation instructions for products not manufactured by GAF. Please consult the material manufacturer for their MSDS and installation instructions where appropriate. t300'%&$,4Use minimum 3/8" (10mm) plywood or OSB decking as recommended by APA-The Engineered Wood Assn. Wood decks must be well-seasoned and supported having a maximum 1/8" (3mm) spacing, using minimum nominal 1"(25mm) thick lumber, a maximum 6" (152mm) width, having adequate nail-holding capacity and a smooth surface. -

Persian Ugs Kobo Audiobook.Pdf

LESSON NOTES Basic Bootcamp #1 Self Introductions - Basic Greetings in Persian CONTENTS 2 Persian 2 English 2 Romanization 2 Vocabulary 3 Sample Sentences 4 Vocabulary Phrase Usage 6 Grammar # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2013 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PERSIAN . : .1 . : .2 . : .3 . : .4 ENGLISH 1. BEHZAD: Hello. I'm Behzad. What's your name? 2. MARY: Hello Behzad. My name is Mary. 3. BEHZAD: Nice to meet you. 4. MARY: You too. ROMANIZATION 1. BEHZAD: Salam, man Behzad am. Esme shoma chi e? 2. MARY: Salam Behzad, Esme man Mary e. 3. BEHZAD: Az ashnayi ba shoma khoshvaght am. 4. MARY: Man ham hamintor. VOCABULARY PERSIANPOD101.COM BASIC BOOTCAMP #1 - SELF INTRODUCTIONS - BASIC GREETINGS IN PERSIAN 2 Persian Romanization English Class Man ham hamintor. me too phrase Az ashnayi ba shoma khoshvaght Nice to meet you sentence am. ... Esme man (...) e. My name is (...). sentence Esme shoma chi e? What’s your name? sentence salaam hello interjection man I, me pronoun hastam (I) am verb esm name noun SAMPLE SENTENCES : . : . . . ali: man gorosne hastam. zahraa: man ham man faateme hastam. az aashnaayi baa shomaa hamin tor. khoshvaghtam. Ali: I'm hungry. Zahra: Me too. My name is Fateme. Nice to meet you. . esm-e man zeinabe. esm-e man naaser e. esm-e shomaa chie? My name is Zeinab. My name is Naser. What is your name? . . Oo hich vaght be man salaam nemikonad. Az man aks nagir. He never says hello to me. "Don't take photos of me." . Man ta hala chenin chizi nadidam. Kheili khaste hastam I have never seen such a thing. -

Paraneoplastic Syndromes in Patients with Ovarian Neoplasia

202 Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine Volume 86 April 1993 Paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with ovarian neoplasia C N Hudson MChir FRCS FRCOG1 Marigold Curling MB BS2 Penelope Potsides' D G Lowe MD MRCPath MIBiol' 'The Association of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, NE Thames Region and 2the Department ofHistopathology, St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical College, London EClA 7BE Keywords: paraneoplastic syndromes; ovarian cancer; prevalence Summary data at presentation of 908 patients with primary The prevalence of several paraneoplastic syndromes epithelial ovarian cancer, collected prospectively in associated with ovarian cancer was determined from the North East Thames Region. a clinicopathological study of 908 patients with primary ovarian malignancy in the North East Thames Data source Region. The diversity and rarity of these manifesta- In the 1970s a data bank for ovarian cancer in the tions are great and the explanation for them is North East Metropolitan Region was set up by difficult. Circumstantial evidence suggests that in the Association of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists some cases an autoimmune phenomenon is the most of the Region in association with the Regional plausible cause. Histopathologists Group. Data was entered either by pathologist or clinician, and as soon as a case Introduction was notified, the clinical data on an agreed proforma Paraneoplastic syndromes are systemic manifestations were obtained from the surgeon concerned - he/ ofcancer that cannot readily be explained by the local she provided details of the mode of presentation, or metastatic effects of a tumour or of hormones investigation, operative staging, and treatment. indigenous to the tissue in which the tumour arises. Histological material was reviewed centrally by The syndromes fall into four broad groups, in which the two of the authors. -

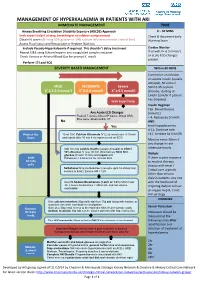

Management of Hyperkalaemia in Patients with Aki Immediate Management Time

MANAGEMENT OF HYPERKALAEMIA IN PATIENTS WITH AKI IMMEDIATE MANAGEMENT TIME ≥ Airway Breathing Circulation Disability Exposure (ABCDE) Approach 0 – 30 MINS Seek expert help if airway, breathing or circulation compromised Check & document Early Obtain IV access (If using 50% glucose or 10% calcium infusions consider central line) Warning Score Assess Fluid status and Resuscitate or Replace fluid loss Exclude Pseudo-Hyperkalaemia if required. This shouldn’t delay treatment Cardiac Monitor Repeat U&E using lithium heparin anti-coagulated sample container If unwell, K+ 6.5 mmol/L + or acute ECG changes Check Venous or Arterial Blood Gas for prompt K result P present Perform 12 Lead ECG SEVERITY BASED MANAGEMENT Within 60 MINS Commence an infusion of soluble insulin (usually actrapid), 50 units in MILD MODERATE Severe 50ml 0.9% sodium + + + K 5.5-5.9 mmol/l K 6-6.4 mmol/l K ≥ 6.5 mmol/l chloride, starting at 1ml/hr (2ml/hr if patient has diabetes) Seek Expert help Insulin Regimen Cap. Blood Glucose Any Acute ECG Changes (mmol/L) Peaked T waves, Absent P waves, Broad QRS, < 4: Reduce by 0.5ml/h Sine wave, Bradycardia, VT No AND Yes treat hypoglycaemia 4-11: Continue rate Protect the 10 ml 10% Calcium Gluconate IV (2.26 mmol) over 5-10 min >11: Increase by 0.5ml/h Heart and repeat after 10 min if no improvement on ECG Monitor every 30min if any change in rate Add 10 units soluble Insulin (usually Actrapid) to 250ml otherwise hourly 10% Glucose IV over 30 min (Alternatively 50ml 50% glucose IV over 15 min) and repeat until Dialysis Shift Potassium < 5.5mmol/L for at least 4hrs. -

Workshop on Internationalized Domain Names for Pakistani Languages April 20, 2008

Workshop on Internationalized Domain Names for Pakistani Languages April 20, 2008 Table 1: Tentative tables for public feedback 1 Character Unicode Description Balochi Pashto Punjabi Saraiki Sindhi Torwali ASIWG Decision 2 0600 ARABIC NUMBER SIGN NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 0601 ARABIC SIGN SANAH NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 0601 ARABIC FOOTNOTE MARKER NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 0603 ARABIC SIGN SAFHA NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 0604 <reserved> UNASSIGNED 1 Dr. Sarmad Hussain, Professor and Head, Center for Research in Urdu Language Processing, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Lahore, PAKISTAN. Email: [email protected] , URL: www.crulp.org , www.nu.edu.pk 2 Arabic Script IDN Working Group (ASIWG) [email protected] http://lists.irnic.ir/mailman/listinfo/idna-arabicscript 0605 <reserved> UNASSIGNED 0606 ARABIC-INDIC CUBE ROOT NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 0607 ARABIC-INDIC FOURTH NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED ROOT 0608 ARABIC RAY NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 0609 ARABIC-INDIC PER MILLE NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED SIGN 060A ARABIC-INDIC PER TEN NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED THOUSAND SIGN 060B AFGHANI SIGN NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 060C ARABIC COMMA NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED 060D ARABIC DATE SEPARATOR NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED ؍ 060E ARABIC POETIC VERSE SIGN NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED ؎ 060F ARABIC SIGN MISRA NO NO NO NO NO NO DISALLOWED ؏ 0610 ARABIC SIGN SALLALLAHOU PENDING PENDING PENDING PENDING PENDING PENDING PVALID ALAYHE WASSALLAM 0611 ARABIC SIGN ALAYHE PENDING PENDING -

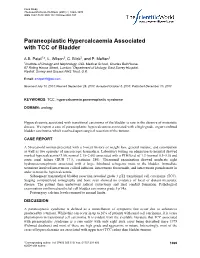

Paraneoplastic Hypercalcaemia Associated with TCC of Bladder

Case Study TheScientificWorldJOURNAL (2004) 4, 1069–1070 ISSN 1537-744X; DOI 10.1100/tsw.2004.187 Paraneoplastic Hypercalcaemia Associated with TCC of Bladder A.B. Patel1,*, L. Wilson2, C. Blick2, and P. Meffan2 1Institute of Urology and Nephrology, UCL Medical School, Charles Bell House, 67 Riding House Street, London; 2Department of Urology, East Surrey Hospital, Redhill, Surrey and Sussex NHS Trust, U.K. E-mail: [email protected] Received July 14, 2004; Revised September 28, 2004; Accepted October 5, 2004; Published December 10, 2004 KEYWORDS: TCC, hypercalcaemia,paraneoplastic syndrome DOMAIN: urology Hypercalcaemia associated with transitional carcinoma of the bladder is rare in the absence of metastatic disease. We report a case of paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia associated with a high-grade, organ-confined bladder carcinoma, which resolved upon surgical resection of the tumour. CASE REPORT A 58-year-old woman presented with a 3-week history of weight loss, general malaise, and constipation as well as two episodes of macroscopic haematuria. Laboratory testing on admission to hospital showed marked hypercalcaemia (3.66, normal 2.15–2.60) associated with a PTH level of 1.3 (normal 0.5–5.5) and acute renal failure (BUN 37.5, creatinine 280). Ultrasound examination showed moderate right hydroureteronephrosis associated with a large, lobulated echogenic mass in the bladder. Immediate treatment involved intravenous colloid infusion, intravenous furosemide, and intravenous pamidronate in order to treat the hypercalcaemia. Subsequent transurethral bladder resection revealed grade 3 pT2 transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). Staging computerised tomography and bone scan showed no evidence of local or distant metastatic disease. The patient then underwent radical cystectomy and ileal conduit formation. -

Artefactual Serum Hyperkalaemia and Hypercalcaemia in Essential Thrombocythaemia J Clin Pathol: First Published As 10.1136/Jcp.53.2.105 on 1 February 2000

J Clin Pathol 2000;53:105–109 105 Artefactual serum hyperkalaemia and hypercalcaemia in essential thrombocythaemia J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.53.2.105 on 1 February 2000. Downloaded from M R Howard, S Ashwell, L R Bond, I Holbrook Abstract the release of potassium ions from platelets Aim—To investigate possible abnormali- which are entrapped within the clot in a serum ties of serum potassium and calcium sample. This phenomenon generally occurs levels in patients with essential thrombo- with platelet counts in excess of 600 × 109/litre, cythaemia and significant thrombocyto- with a roughly predictable increment in serum sis. potassium for every further increase in platelet Methods—24 cases of essential thrombo- count. The potassium level is normalised if the cythaemia with significant thrombocyto- estimation is made using plasma rather than sis (platelet count > 700 × 109/litre) had serum.45 serum potassium and calcium estimations Abnormalities of other ions have not been performed at the time of maximum well described in essential thrombocythaemia. thrombocytosis before treatment, and at Despite the presence of calcium in platelet- the time of low platelet count after dense granules and its secretion from platelets treatment with cytoreductive drugs. Se- during activation, there has been no systematic lected patients were further investigated study of serum calcium levels in patients with with plasma sampling and estimation of essential thrombocythaemia and significantly ionised calcium and parathyroid hor- increased platelet counts. There has been a mone. single case report of serum hypercalcaemia Results—At the time of maximum throm- associated with essential thrombocythaemia. In bocytosis six patients had serum hyperka- this case the hypercalcaemia rapidly resolved laemia (> 5.5 mmol/litre) and five had following reduction of the platelet count.6 We serum hypercalcaemia (> 2.6 mmol/litre). -

20 May 2021 4° 5° 6° 7° 8° 9° 10° 11° 12° 13° 14° 15° 16° 17° 18° 19° 20° 21° 22° 23° 24°

ERC-03/L 20 May 2021 4° 5° 6° 7° 8° 9° 10° 11° 12° 13° 14° 15° 16° 17° 18° 19° 20° 21° 22° 23° 24° LFD54 M < A1 < M 0 G2 DIKEL VALMA LIP233 Z LIR22 LIP329 LIR50 A482 OKDI N14 T216 N141> T ANA > <Y < 6 8 YE L 1> 2 R 4 3 VE LFD < 4 LIP99 CRA TI < 4 E ED R1 9 R 5 > 5 A 1 K < 4 M L G U SO A2 T 5 L L TORLI 8 06 7 MA 7 L 4 2 A LIR3 7 M M P 4 ERIK 2 U ISIP ) W1 1 6 8 0 DIVK P AAL > 8 U 0 LF 1 2 1 M 0 LA ASB D 3 1 > > 3 L 1 5 7 L LIRL LIR N V 4A 4 8 3 9 3 7 7 LIR309A A 95 7 N K > LF 1 2 L 7 LIRRAET ERAV --------- 1 1 R19 LG 2 9 K P - 5 F 3 --- A N 2 9 7 A --- 3 G LIRRUS1 300 305 8 --- R 4 L AP 9 5 2 LIR LIR --- LA AR < 8 M 6 RUR M AM 4 < LID 9B B A D2 DOB M 13 H P 2 67 0 8 R30 T A L 1 Q LI L 9 F E A 2 D S 9 4 54C1 L J L IR300B L 2> 0 SK L A < 1 7 L 4 L 4 E TMA R3C F P 5 G 5 > 9 Z IP328 BCN1 6 A AAA LA K 2 3 1 L LIB 7 A O L M L L 1 1 L < 9 3 B > FM 5 9 9 G N 6 LFD54 LFD MAJ E L H IKO C2 1 9 580 LVIN 5 1 2 2 G O OD < 5 8 6 L W < 5 2 < L ) 1 1 7 > 0 6 0 10 1 R LS ( LGGG GR 1 LAT LIP2 5 6 3 LYBA FIR ( 8 N L LF Z LIP323 2A A T I 2 D 8 0 54C3 2 LIR3 L SA01 1 A 6 6 T 2 T N 1 <U 1 5 D 2 LW LW < HI 1 GR 7 M 9 302B 5 R S LWSS N 6 1 L 6 3 LIR T Z 2 UR 3 6 F I > 01 NIVD GOPA M 4 M 80 EKM K N 1 1 8 3 A T P 3 2 M POULP 2 LIP8A LIP163 3 I A > 17 T AG 7 7 R O 4 3 R O T 1 5 OSN P COR INTO 9 LIP173 B F > 1 < 3 LG U SI Z 7 T2 W ( 2 B P 3 L 6 T 7 T < M CR R L AR3 7 3 AS L 0 41° M LIBA 1 L L 2 4 I Y 9 J > 6 N 4 TA 3 N 8 M M N A 5 M < MAR 6 Q 9 < CHEL < UREN LFM T SEILLE FIR (L 7 9 D B P E 1 < 3 8 6 Y 6 F 5 MD MM Z LIBF KA A N L Y < L ) O 6 9 6 V 1 2 LIP8B SIPRO 8