The Spirit Within Steven C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dxseeeb Syeceb Suquamish News

dxseEeb syeceb Suquamish News VOLUME 15 JUNE 2015 NO. 6 Reaching Milestones In this issue... Suquamish celebrates opening of new hotel tower and seafood plant Seafoods Opening pg. 3 CKA Mentors pg. 4 Renewal Pow Wow pg. 8 2 | June 2015 Suquamish News suquamish.org Community Calendar Featured Artist Demonstration Museum Movie Night the Veterans Center Office at (360) 626- contact Brenda George at brendageorge@ June 5 6pm June 25 6pm 1080. The Veterans Center is also open clearwatercasino.com. See first-hand how featured artist Jeffrey Join the museum staff for a double feature every Monday 9am-3pm for Veteran visit- Suquamish Tribal Veregge uses Salish formline designs in his event! Clearwater with filmmaker Tracy ing and Thursdays for service officer work Gaming Commission Meetings works, and the techniques he uses to merge Rector from Longhouse Media Produc- 9am-3pm. June 4 & 8 10am two disciplines during a demonstration. tions. A nonfiction film about the health The Suquamish Tribal Gaming Commis- For more information contact the Suqua- of the Puget Sound and the unique rela- Suquamish Elders Council Meeting sion holds regular meetings every other mish Museum at (360) 394-8499. tionship of the tribal people to the water. June 4 Noon Then Ocean Frontiers by filmmaker Karen The Suquamish Tribal Elders Council Thursday throughout the year. Meetings nd Museum 32 Anniversary Party Anspacker Meyer. An inspiring voyage to meets the first Thursday of every month in generally begin at 9am, at the Suquamish June 7 3:30pm coral reefs, seaports and watersheds across the Elders Dining Room at noon. -

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation As a National Heritage Area

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION APRIL 2010 The National Maritime Heritage Area feasibility study was guided by the work of a steering committee assembled by the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Steering committee members included: • Dick Thompson (Chair), Principal, Thompson Consulting • Allyson Brooks, Ph.D., Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation • Chris Endresen, Office of Maria Cantwell • Leonard Forsman, Chair, Suquamish Tribe • Chuck Fowler, President, Pacific Northwest Maritime Heritage Council • Senator Karen Fraser, Thurston County • Patricia Lantz, Member, Washington State Heritage Center Trust Board of Trustees • Flo Lentz, King County 4Culture • Jennifer Meisner, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation • Lita Dawn Stanton, Gig Harbor Historic Preservation Coordinator Prepared for the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation by Parametrix Berk & Associates March , 2010 Washington State NATIONAL MARITIME HERITAGE AREA Feasibility Study Preface National Heritage Areas are special places recognized by Congress as having nationally important heritage resources. The request to designate an area as a National Heritage Area is locally initiated, -

In the Spirit of the Ancestors: Contemporary Northwest Coast Art at the Burke Museum

In the Spirit of the Ancestors: Contemporary Northwest Coast Art at the Burke Museum. Robin K. Wright and Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, eds. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 150 pp.* Reviewed by Jay Miller In the Spirit of the Ancestors inaugurates a series from the Bill Holm Center Series titled “Native Art of the Pacific Northwest.” Its eight chapters bring together working artists and scholars from the entire Pacific coastline, assessing developments since the landmark “A Time of Gathering” exhibition and book that marked the 1989 centennial of Washington State as well as the 2006 exhibition with the same title as this book. It also profusely illustrates items from the Burke collection of 2,400 recent Northwest Coast art works. Shaun Peterson’s “Coast Salish Design: An Anticipated Southern Analysis” describes and illustrates with examples his struggles with mastering his ancestral art tradition, despite strong financial and regional pressures to make north coast formline style art, which is recognizable to non-specialist audiences and sells well. Learning from museum collections, older artists, and trial and error, Peterson realized Salish designs were defined by “cutout negative areas…to suggest movement” (14-15). His epiphany came with wing designs, whose key elements are crescents and wedges, not a dominant eye indicating joint mobility. Intended mostly for private and family use, Salish art was not public art, though many aspects of it have now become commercialized as savvy clientele grows within the United States and British Columbia triangle marked by the cities of Seattle, Vancouver, and Victoria. Margaret Blackman discusses the collection of 1,166 Northwest silkscreen prints that she and her husband assembled, which has been housed at the Burke Museum since 1998. -

Title Page: Arial Font

2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Heritage Capital Projects Funding? Does the project your organization is planning involve an historic property or support access to heritage? If so… it may be eligible for state HCP funding. WASHINGTON STATEExamples: HISTORICAL SOCIETY GRANT FUNDS FOR CAPITAL PROJECTS Historic Seattle PDA – Rehabilitation of THAT SUPPORT HERITAGE Washington Hall IACC CONFERENCE 2016 - OCTOBER 19, 2016 City Adapts and Reuses Old City Hall Park District Preserves Territorial History Tacoma Metropolitan Parks City of Bellingham - 1892 Old City Hall Preservation of the Granary at the Adaptively Reused as Whatcom Museum Fort Nisqually Living History Museum Multi-phased Window Restoration Project Point Defiance Park, Tacoma Suquamish Indian Nation’s Museum City Restores Station for Continued Use The Suquamish Indian Nation Suquamish Museum Seattle Dept. of Transportation King Street Station Restoration 1 2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Small Town Renovates its Town Hall City Builds Park in Recognition of History City of Tacoma – Chinese Reconciliation Park Town of Wilkeson – Town Hall Renovation Port Rehabilitates School and Gym Public Facilities District Builds New Museum Port of Chinook works with Friends of Chinook School – Chinook School Rehabilitation as a Community Center Richland Public Facilities District –The Reach City Preserves & Interprets Industrial History City Plans / Builds Interpretive Elements City of DuPont Dynamite Train City of Olympia – Budd Inlet Percival Landing Interpretive Elements 2 2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Port: Tourism as Economic Development Infrastructure That Creates Place Places and spaces – are social and community infrastructure Old and new, they connect us to our past, enhance our lives, and our communities. -

Suquamish Tribe 2017 Multi Hazard Mitigation Plan

Section 8 – Tsunami The Suquamish Tribe Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan 2017 The Suquamish Tribe Port Madison Indian Reservation November 5, 2017 Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe (This Page intentionally left blank) Multi- Hazard Mitigation Plan Page i Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe The Suquamish Tribe Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan Prepared for: The Suquamish Tribe, Port Madison Indian Reservation Funded by: The Suquamish Tribe & Federal Emergency Management Agency Pre-Disaster Mitigation Competitive Grant Program Project #: PDMC-10-WAIT-2013-001/Suquamish Tribe/Hazard Mitigation Plan Agreement #: EMS-2014-PC-0002 Prepared by: The Suquamish Office of Emergency Management Cherrie May, Emergency Management Coordinator Consultants: Eric Quitslund, Project Consultant Aaron Quitslund, Project Consultant Editor: Sandra Senter, Planning Committee Community Representative October, 2017 Multi- Hazard Mitigation Plan Page ii Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe (This Page intentionally left blank) Multi- Hazard Mitigation Plan Page iii Multi-Hazard Mitigation Plan The Suquamish Tribe Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... iv Table of Tables ............................................................................................................................ viii Table of Maps ............................................................................................................................... -

Singletary Cv

PRESTON SINGLETARY Born 1963, San Francisco, CA Tribal Affiliation: Tlingit EDUCATION 1984- The Pilchuck Glass School, Stanwood, WA 1999 Studied with Lino Tagliapietra, Checco Ongaro, Benjamin Moore, Dorit Brand, Judy Hill, Dan Daily, and Pino Signoretto AWARDS 2013 Mayor’s Art Award, Seattle, WA Visual Arts Fellowship, Artist Trust, Seattle, WA 2010 Honorary doctorate, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma, WA 2009 National Native Artist Exchange Award, New England Foundation for the Arts, Boston, MA 2004 1st Place Contemporary Art, Sealaska Heritage Foundation, “Celebration 2004,” AK 2003 Rakow Commission, Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY 2002 Seattle Arts Commission, Purchase Award 2000 Mayor’s Award and 1st, 2nd, 3rd Diversified Arts, Best of Division, Indian Art NW, Portland, OR 1999 1st, 2nd, 3rd place, Diversified Arts, Best of Division, Indian Art NW, Portland, OR 1998 1st place, Diversified Arts, Best of Aivision, Indian Art NW, Portland, OR 1998 Jon & Mary Shirley Scholarship, Pratt Fine Arts Center 1995 Washington Mutual Foundation, Study Grant, The Pilchuck Glass School. 1988- The Glass House Goblet Competition Purchase Award 1990 1985 Work Study Grant, The Institute of Alaska Native Arts SOLO GALLERY EXHIBITIONS 2018 Traver Gallery, Seattle, WA – The Air World 2017 Spirit wrestler Gallery, Vancouver, Canada – Pacific Currents Traver Gallery, Seattle, WA – Premonitions of Water Schantz Gallery, Stockbridge, MA – Mystic Figures Blue Rian Gallery, Santa Fe, NM – Journey Through Air to the Sky World 2016 Traver Gallery, Seattle, -

VKP Visitorguide-24X27-Side1.Pdf

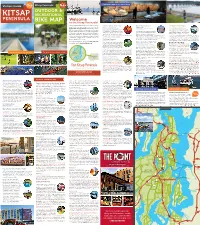

FREE FREE MAP Kitsap Peninsula MAP DESTINATIONS & ATTRACTIONS Visitors Guide INSIDE INSIDE Enjoy a variety of activities and attractions like a tour of the Suquamish Museum, located near the Chief Seattle grave site, that tell the story of local Native Americans Welcome and their contribution to the region’s history and culture. to the Kitsap Peninsula! The beautiful Kitsap Peninsula is located directly across Gardens, Galleries & Museums Naval & Military History Getting Around the Region from Seattle offering visitors easy access to the www.VisitKitsap.com/gardens & Memorials www.VisitKitsap.com/transportation Natural Side of Puget Sound. Hop aboard a famous www.VisitKitsap.com/arts-and-culture visitkitsap.com/military-historic-sites- www.VisitKitsap.com/plan-your-event www.VisitKitsap.com/international-visitors WA State Ferry or travel across the impressive Tacaoma Visitors will find many places and events that veterans-memorials The Kitsap Peninsula is conveniently located Narrows Bridge and in minutes you will be enjoying miles offer insights about the region’s rich and diverse There are many historic sites, memorials and directly across from Seattle and Tacoma and a short of shoreline, wide-open spaces and fresh air. Explore history, culture, arts and love of the natural museums that pay respect to Kitsap’s remarkable distance from the Seattle-Tacoma International waterfront communities lined with shops, art galleries, environment. You’ll find a few locations listed in Naval, military and maritime history. Some sites the City & Community section in this guide and many more choices date back to the Spanish-American War. Others honor fallen soldiers Airport. One of the most scenic ways to travel to the Kitsap Peninsula eateries and attractions. -

American Native Arts Auction Thursday February 11Th @ 4:00PM 16% Buyers Premium In-House 19% Buyers Premium Online/Phone 717 S Third St Renton (425) 235-6345

American Native Arts Auction Thursday February 11th @ 4:00PM 16% Buyers Premium In-House 19% Buyers Premium Online/Phone 717 S Third St Renton (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTIONS polychrome zig-zag false embroidery design. It has an old 2" glue repair near top rim, Lots 1,000’s End @ 7:00PM otherwise excellent condition. Late 19th or early 20th century. Lot Description 4B Antique Tlingit Large Indian Basket 8"x10". Spruce root basket with bright orange 1 Antique Tlingit Rattle Top Indian Basket polychrome false embroidery. It has a few 3.75"x6.5". Spruce root basket with small splits to top rim and three small splits polychrome geometric arrow motifs and in the side walls. Excellent condition spiral on lid. Excellent condition. Late 19th otherwise. Late 19th or early 20th century. or early 20th century. 4C Antique Tlingit Large Indian Basket 8"x10". 2 Antique Tlingit Rattle Top Indian Basket An exceptional spruce root basket with 4.25"x7.5". Spruce root basket with geometric diamond motif in false repeating polychrome geometric key motifs. embroidery. Excellent condition. Late 19th Excellent condition. Late 19th or early 20th or early 20th century. century. Collection of artist Danny Pierce, 4D Antique Tlingit Large Indian Basket Washington. 7.5"x10". Spruce root basket with 3 Antique Tlingit Rattle Top Indian Basket polychrome cross and box motif in false 3.75"x6.25". Spruce root basket with embroidery. It has a .5" area of slight repeating polychrome geometric cross and chipping to top rim, otherwise excellent diamond motifs. Excellent condition. Late condition. Late 19th or early 20th century. -

NATIVE AMERICAN HIGHLIGHTS of WASHINGTON Statepdf

NATIVE AMERICAN HIGHLIGHTS OF WASHINGTON STATE & OLYMPIC NATIONAL PARK (10 day) Fly-Drive Native American culture in the Pacific Northwest is unique and celebrated through the bold art and style of the diverse Northwest Coastal tribes that have been connected to one another for thousands of years through trade. This link is apparent in their art - masks, canoes, totem poles, baskets, clothing and bentwood boxes - using cedar, copper and other materials readily accessible in nature. Their art tells the stories of their lives through the centuries, passing history and wisdom from generation to generation. Native American culture is present in everyday life in Seattle from the totems that grace the parks and public spaces to the manhole covers on the streets. Along your journey, you will experience Seattle’s unique urban attractions, Bellingham’s historic seaport ambiance and the wild beauty of the Olympic Peninsula from lush old-growth forests to spectacular, untamed beaches. En route you’ll encounter the many ways Native American culture is woven into the fabric of the Pacific Northwest. Day 1 Arrive Seattle Pike Place Market 85 Pike Street Seattle, WA 98101 www.pikeplacemarket.org Pike Place Market is a hot spot for fresh food sourced from nearby farms, cocktails created by favorite mixologists and a place to rub elbows with both Seattle locals and visitors. From flying fish to street musicians to gorgeous flowers and an array of delicious food options, this 100+ year-old national historic district is a vibrant neighborhood, welcoming over 10 million visitors annually to this super cool hub. Steinbrueck Native Gallery (Near Pike Place Market) 2030 Western Avenue Seattle, WA 98121 www.steinbruecknativegallery.com Highlights: Works by long- established First Nations masters and talented emerging artists. -

Bibliography for S'abadeb-- the Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian, and Anna Elam, TRC Coordinator

Bibliography for S'abadeb-- The Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian, and Anna Elam, TRC Coordinator Books for Adults: the SAM/Dorothy Stimson Bullitt Library Books are available in the Reading Room of the Bullitt Library (Seattle Art Museum, Fifth Floor, South Building). *= books selected for in-gallery reading areas American Indian sculpture: a study of the Northwest coast, by special arrangement with the American Ethnological Society by Wingert, Paul S. (American Indian sculpture: a study of the Northwest coast, by special arrangement with the American Ethnological Society, 1949). E 98 A7 W46 * Aunt Susie Sampson Peter: the wisdom of a Skagit elder by Hilbert, Vi; Miller, Jay et al. (Federal Way, WA: Lushootseed Press, 1995). E 99 S2 P48 Coast Salish essays by Suttles, Wayne P. et al. (Vancouver, BC: Talonbooks; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1987). E 99 S2 S8 The Coast Salish of British Columbia by Barnett, Homer (Eugene: University of Oregon, 1955). E 99 S2 B2 * Contemporary Coast Salish art by Blanchard, Rebecca and Davenport, Nancy. (Seattle: Stonington Gallery : University of Washington Press, 2005). E 99 S2 B6 Crow's shells: artistic basketry of Puget Sound by Marr, Carolyn and Thompson, Nile. (Seattle: Dushuyay Publications, 1983). E 98 B3 T5 * Eyes of Chief Seattle by the Suquamish Museum. (Suquamish, WA: Suquamish Museum, 1985). E 99 S7 S8 * Gram Ruth Sehome Shelton: the wisdom of a Tulalip elder by Hilbert, Vi; Miller, Jay et al. (Federal Way, WA: Lushootseed Press, 1995). E 99 S2 S43 Haboo: Lushootseed literature in English by Hilbert, Vi and Hilbert, Ron. -

Americas (Northwest Coast)

Americas (Northwest Coast) Select the caption you wish to read from the index below or scroll down to read them all in turn Americas (Northwest Coast) 1 - Cedar bark waistcoat 2 - Shaman’s rattle 3 - Raven rattle 4 - Feasting dish 5 - Feasting dish 6 - Feasting dish 7 - Crooked Beak of Heaven (Galokwudzuwis) 8 - Portrait figure 9 - Spoon 10 - Feasting dishes 11 - Silver Pendant 12 - Bowl 13 - Feasting spoon (sdláagwaal xasáa) 14 - Pendant amulets 15 - Bowl 16 - Feasting spoon 17 - Feasting spoon 18 - Feasting spoon 19 - Feasting spoons 20 - Bow and arrows 21 - War club (chitoolth) 22 - Whalebone club (chitoolth) 23 - Adze head 24 - Scraper and maul head 25 - Crest pipe 26 - Panel pipe 27 - Model crest pole 28 - Model crest pole 29 - Model crest pole 30 - Model crest pole 31& 33 - Fish hooks 32 - Jig-hook 34 - Trolling hooks 35 - War club 36 - Beaver-tooth gouges 37 - Wood-working tool 38 - Wood-working tool 39 - Labret 40 - Painting of Whale 41 - Basketry-covered flasks 42 - Chief’s Box Killer Whale 43 - Harpoon cover 44 - Canoe paddle 45 - Basket (t'cayas) 46 - Baskets 47 - Burden basket 48 - Bark beater 49 - Clothing element 50 - Cedar bark cape 1 - Cedar bark waistcoat Mid-1990s Nuu-chah-nulth nation The waistcoat and shaman’s rattle below were presented to Graham Searle in June 1998, a local museum volunteer. He was named Tic Ma (teech mah) which means ‘generous heart’ and he became the Keeper of the Totem Pole. 2 - Shaman’s rattle Joe David (born 1946), late 20th century Nuu-chah-nulth nation This shaman’s tool enables him to communicate with ancestral spirits. -

Annual Report 2015

2015 Annual Report Greetings from the Director of the Suquamish Foundation Hello Friends, It is my honor to greet you in our 2015 Annual Report as this year marks my first as Director of the Suquamish Foundation. My name is Robin Sigo. I am a Suquamish Tribal Member and life-long resident of Suquamish. I have a Master’s of Social Work from the University of Washington and several years’ experience in grant development and research for the Suqua- mish Tribe and our ground-breaking community wellness program, Healing of the Canoe. I also serve as the Director of Grants for the Suquamish Tribe and am the Treasurer of the elect- ed governing body of the Suquamish Tribal Council. As I step into the Director’s role for the Suquamish Foundation, I not only see the highlights of accomplishments for 2015 but for the decade preceding it. For 2015; we continued to meet our mission “To build on the Suquamish Tribe’s ancestral vision to enhance the culture, education, environment and physical well-being of the Tribe and the greater Suquamish community”. We continued to work with our dedicated Board Members, Rich Deline, Frances Malone, Luther Mills, Jr., Sarah van Gelder, Noel Purser, Jim Nall and Marilyn Wandrey. We focused on fund-raising for the Suquamish Museum and Arts Center, to expand its’ programs and collections, as well as assisting with the tremendously successful First Annual International Salish Wool Weavers Symposium that brought over 200 participants and weavers from Canada and the U.S. to preserve, strengthen and study the traditional art of Salish weaving.