Suquamish Tribe 2017 Multi Hazard Mitigation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suquamish Tribe Experience

Tribal State Transportation Conference Suquamish Clearwater Casino Resort September 28th, 2016 Suquamish Tribe Experience Russell Steele Scott Crowell Robert B. Gatz Port Madison Indian Reservation encompasses 7,657 acres of the Kitsap Peninsula. The Reservation fronts on Puget Sound. 1,200 Tribal Members The land within the Reservation is checker boarded with both fee and trust parcels. The Tribe is actively purchasing back fee land and has Introduction recently exceeded 50% of total land area The road system consists mostly of Kitsap County roads and State Route 305 We have very low mileage of tribal roads in the BIA IRR inventory Kitsap Transit provides transit service to the reservation with the connection Poulsbo, Kingston, and Washington State Ferries on Bainbridge Island and Kingston. The Washington State Ferries provide links to Seattle and Edmonds. The Tribe owns & operates: Elders buses School buses serving Chief Kitsap Academy and the Marion Forsman-Boushie Early Learning Center Casino buses providing shuttle to and from the Casino Tribal from nearby hotels and connection with the state ferry Transportation terminals at Bainbridge Island and Kingston Kiana Lodge dock Suquamish dock Tribal streets and roads mostly in Tribal Housing developments Paved pedestrian path through White Horse Golf Course BIA IRR Funding HUD & ICDBG Funding Project Tribal Hard Dollars Senate Earmark Funding Federal Highway Administration Sources Tribal Gas Tax Funds Puget Sound Regional Council Award Safe Routes to Schools Funding -

Dxseeeb Syeceb Suquamish News

dxseEeb syeceb Suquamish News VOLUME 15 JUNE 2015 NO. 6 Reaching Milestones In this issue... Suquamish celebrates opening of new hotel tower and seafood plant Seafoods Opening pg. 3 CKA Mentors pg. 4 Renewal Pow Wow pg. 8 2 | June 2015 Suquamish News suquamish.org Community Calendar Featured Artist Demonstration Museum Movie Night the Veterans Center Office at (360) 626- contact Brenda George at brendageorge@ June 5 6pm June 25 6pm 1080. The Veterans Center is also open clearwatercasino.com. See first-hand how featured artist Jeffrey Join the museum staff for a double feature every Monday 9am-3pm for Veteran visit- Suquamish Tribal Veregge uses Salish formline designs in his event! Clearwater with filmmaker Tracy ing and Thursdays for service officer work Gaming Commission Meetings works, and the techniques he uses to merge Rector from Longhouse Media Produc- 9am-3pm. June 4 & 8 10am two disciplines during a demonstration. tions. A nonfiction film about the health The Suquamish Tribal Gaming Commis- For more information contact the Suqua- of the Puget Sound and the unique rela- Suquamish Elders Council Meeting sion holds regular meetings every other mish Museum at (360) 394-8499. tionship of the tribal people to the water. June 4 Noon Then Ocean Frontiers by filmmaker Karen The Suquamish Tribal Elders Council Thursday throughout the year. Meetings nd Museum 32 Anniversary Party Anspacker Meyer. An inspiring voyage to meets the first Thursday of every month in generally begin at 9am, at the Suquamish June 7 3:30pm coral reefs, seaports and watersheds across the Elders Dining Room at noon. -

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation As a National Heritage Area

Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION Washington State National Maritime Heritage Area Feasibility Study for Designation as a National Heritage Area WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION APRIL 2010 The National Maritime Heritage Area feasibility study was guided by the work of a steering committee assembled by the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. Steering committee members included: • Dick Thompson (Chair), Principal, Thompson Consulting • Allyson Brooks, Ph.D., Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation • Chris Endresen, Office of Maria Cantwell • Leonard Forsman, Chair, Suquamish Tribe • Chuck Fowler, President, Pacific Northwest Maritime Heritage Council • Senator Karen Fraser, Thurston County • Patricia Lantz, Member, Washington State Heritage Center Trust Board of Trustees • Flo Lentz, King County 4Culture • Jennifer Meisner, Washington Trust for Historic Preservation • Lita Dawn Stanton, Gig Harbor Historic Preservation Coordinator Prepared for the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation by Parametrix Berk & Associates March , 2010 Washington State NATIONAL MARITIME HERITAGE AREA Feasibility Study Preface National Heritage Areas are special places recognized by Congress as having nationally important heritage resources. The request to designate an area as a National Heritage Area is locally initiated, -

Title Page: Arial Font

2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Heritage Capital Projects Funding? Does the project your organization is planning involve an historic property or support access to heritage? If so… it may be eligible for state HCP funding. WASHINGTON STATEExamples: HISTORICAL SOCIETY GRANT FUNDS FOR CAPITAL PROJECTS Historic Seattle PDA – Rehabilitation of THAT SUPPORT HERITAGE Washington Hall IACC CONFERENCE 2016 - OCTOBER 19, 2016 City Adapts and Reuses Old City Hall Park District Preserves Territorial History Tacoma Metropolitan Parks City of Bellingham - 1892 Old City Hall Preservation of the Granary at the Adaptively Reused as Whatcom Museum Fort Nisqually Living History Museum Multi-phased Window Restoration Project Point Defiance Park, Tacoma Suquamish Indian Nation’s Museum City Restores Station for Continued Use The Suquamish Indian Nation Suquamish Museum Seattle Dept. of Transportation King Street Station Restoration 1 2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Small Town Renovates its Town Hall City Builds Park in Recognition of History City of Tacoma – Chinese Reconciliation Park Town of Wilkeson – Town Hall Renovation Port Rehabilitates School and Gym Public Facilities District Builds New Museum Port of Chinook works with Friends of Chinook School – Chinook School Rehabilitation as a Community Center Richland Public Facilities District –The Reach City Preserves & Interprets Industrial History City Plans / Builds Interpretive Elements City of DuPont Dynamite Train City of Olympia – Budd Inlet Percival Landing Interpretive Elements 2 2016 IACC Conference - S24 Heritage Project 10/19/2016 Funding Port: Tourism as Economic Development Infrastructure That Creates Place Places and spaces – are social and community infrastructure Old and new, they connect us to our past, enhance our lives, and our communities. -

Tribal Ceded Areas in Washington State

Blaine Lynden Sumas Fern- Nooksack Oroville Metaline dale Northport Everson Falls Lummi Nation Metaline Ione Tribal Ceded Areas Bellingham Nooksack Tribe Tonasket by Treaty or Executive Order Marcus Samish Upper Kettle Republic Falls Indian Skagit Sedro- Friday Woolley Hamilton Conconully Harbor Nation Tribe Lyman Concrete Makah Colville Anacortes Riverside Burlington Tribe Winthrop Kalispel Mount Vernon Cusick Tribe La Omak Swinomish Conner Twisp Tribe Okanogan Colville Chewelah Oak Stan- Harbor wood Confederated Lower Elwha Coupeville Darrington Sauk-Suiattle Newport Arlington Tribes Klallam Port Angeles The Tulalip Tribe Stillaguamish Nespelem Tribe Tribes Port Tribe Brewster Townsend Granite Marysville Falls Springdale Quileute Sequim Jamestown Langley Forks Pateros Tribe S'Klallam Lake Stevens Spokane Bridgeport Elmer City Deer Everett Tribe Tribe Park Mukilteo Snohomish Grand Hoh Monroe Sultan Coulee Port Mill Chelan Creek Tribe Edmonds Gold Bothell + This map does not depict + Gamble Bar tribally asserted Index Mansfield Wilbur Creston S'Klallam Tribe Woodinville traditional hunting areas. Poulsbo Suquamish Millwood Duvall Skykomish Kirk- Hartline Almira Reardan Airway Tribe land Redmond Carnation Entiat Heights Spokane Medical Bainbridge Davenport Tribal Related Boundaries Lake Island Seattle Sammamish Waterville Leavenworth Coulee City Snoqualmie Duwamish Waterway Bellevue Bremerton Port Orchard Issaquah North Cheney Harrington Quinault Renton Bend Cashmere Rockford Burien Wilson Nation -

Tulalip Tribes V. Suquamish Tribe

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT TULALIP TRIBES, No. 13-35773 Plaintiff-Appellant, D.C. Nos. v. 2:05-sp-00004- RSM SUQUAMISH INDIAN TRIBE, 2:70-cv-09213- Defendant-Appellee, RSM and OPINION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; SWINOMISH TRIBAL COMMUNITY; JAMESTOWN S’KLALLAM TRIBE; LOWER ELWHA BAND OF KLALLAMS; PORT GAMBLE S’KLALLAM TRIBE; NISQUALLY INDIAN TRIBE; SKOKOMISH INDIAN TRIBE; UPPER SKAGIT INDIAN TRIBE; LUMMI NATION; NOOKSACK INDIAN TRIBE OF WASHINGTON STATE; WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE; QUINAULT INDIAN NATION; STILLAGUAMISH TRIBE; PUYALLUP TRIBE; MUCKLESHOOT INDIAN TRIBE; QUILEUTE INDIAN TRIBE, Real-parties-in-interest. 2 TULALIP TRIBES V. SUQUAMISH INDIAN TRIBE Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington Ricardo S. Martinez, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted October 8, 2014—Seattle, Washington Filed July 27, 2015 Before: Richard A. Paez, Jay S. Bybee, and Consuelo M. Callahan, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge Paez SUMMARY* Indian Law The panel affirmed the district court’s summary judgment in a treaty fishing rights case in which the Tulalip Tribes sought a determination of the scope of the Suquamish Indian Tribe’s usual and accustomed fishing grounds and stations. The Tulalip Tribes invoked the district court’s continuing jurisdiction as provided by a permanent injunction entered in 1974. The panel affirmed the district court’s conclusion that certain contested areas were not excluded from the Suquamish Tribe’s usual and accustomed fishing grounds and stations, as determined by the district court in 1975. * This summary constitutes no part of the opinion of the court. -

Who Is Who in the Lower Duwamish Waterway

Who Is Who in the Lower Duwamish Waterway Federal Government Agency for Toxic Substances This federal health agency funded WA Department of Health to complete a public health assessment of the chemical contamination in LDW and su pports communit y and Disease Registry engagement to prevent harmful effects related to exposure of chemical contamination. In addition to managing t he Howard Hanson dam and maintaining the navigation channel within the Duwamish Waterway, the US Army Corps of Engineers serves as t he primary point of contact for the interagency Dredged Material Management Program. The agency regulates activities in waters of t he United States, including wetlands, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers through its permitting authority under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. Where such actions are within Superfund sites, EPA and the Corps of Engineers coordinate on review of the proposed action. The Corps of Engineers is also providing EPA technical support in overseeing LDW Superfund work. US Coast Guard If oil spills occur in the LDW, the US Coast Guard responds, in coordination with EPA, Ecology, and others. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is the lead agency for cleanup of the sediments in the Lower Duwamish Waterway (LDW), Ha rbor Island East and West U.S. Environmental Waterway, Lockheed West Seattle, and Pacific Sound Resources, under CERCLA (commonly cal led Superfund). EPA is also using CERCLA and ot her environmental authorities Protection Agency to require studies and cleanup of several sites next to the LDW. EPA helps respond to spills on land. Tribes The Duwamish Tribe has been in the Seattle/Greater King Cou nty area since time immemorial. -

Suquamish Crab Regulation

SUQUAMISH CRAB REGULATION AFFECTED ORGANIZATIONS: WDFW, and AFFECTED TRIBES DATE: September 28, 2020 REGULATION NUMBER 20-111S REGULATIONS MODIFIED: 20-91S SPECIES: Crab FISHERY TYPE: Commercial and C&S EFFECTIVE DATE: September 28, 2020 HARVEST LOCATIONS, POT LIMITS AND -SEASONS BY REGION: This regulation lists harvest areas, harvest openings and harvest restrictions for Suquamish tribal fishers. This regulation may be amended by subsequent emergency regulations. Region 1 Commercial MFSFCA 20A, 20B, 21A, 22A, and 22B Closed areas: 1) Chuckanut Bay, Samish Bay, and Padilla Bay east of a line drawn from the western tip of Samish Island to the westernmost point on Hat Island and southeast to the shore on the main land just to the east of Indian Slough. 2) Bellingham Bay is closed north of a line from Point Francis to Post Point. Hale Pass is closed northwest of a line from Pont Francis to the red and green buoy southeast of Point Francis, then to the northernmost tip of Eliza Island, then along the eastern shore of the island to its southernmost tip, and then north of a line from the southernmost tip of Eliza Island to Carter Point. Open: 8:00AM Wednesday, September 30, 2020 Close: 4:00PM Sunday, October 4, 2020 Gear limit: 40 tagged pots per boat Subsistence MFSFCA 20A, 20B, 22A, and 21A (west of a line drawn from the Sinclair Island Light (SE Point of Sinclair Island) and Carter Point on Lummi Island Open: 8:00AM Tuesday, June 30, 2020 Close: 8:00PM Monday, May 31, 2021 or when the treaty share is harvested (not to exceed 2.2 million pounds), whichever comes first. -

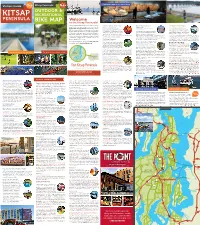

VKP Visitorguide-24X27-Side1.Pdf

FREE FREE MAP Kitsap Peninsula MAP DESTINATIONS & ATTRACTIONS Visitors Guide INSIDE INSIDE Enjoy a variety of activities and attractions like a tour of the Suquamish Museum, located near the Chief Seattle grave site, that tell the story of local Native Americans Welcome and their contribution to the region’s history and culture. to the Kitsap Peninsula! The beautiful Kitsap Peninsula is located directly across Gardens, Galleries & Museums Naval & Military History Getting Around the Region from Seattle offering visitors easy access to the www.VisitKitsap.com/gardens & Memorials www.VisitKitsap.com/transportation Natural Side of Puget Sound. Hop aboard a famous www.VisitKitsap.com/arts-and-culture visitkitsap.com/military-historic-sites- www.VisitKitsap.com/plan-your-event www.VisitKitsap.com/international-visitors WA State Ferry or travel across the impressive Tacaoma Visitors will find many places and events that veterans-memorials The Kitsap Peninsula is conveniently located Narrows Bridge and in minutes you will be enjoying miles offer insights about the region’s rich and diverse There are many historic sites, memorials and directly across from Seattle and Tacoma and a short of shoreline, wide-open spaces and fresh air. Explore history, culture, arts and love of the natural museums that pay respect to Kitsap’s remarkable distance from the Seattle-Tacoma International waterfront communities lined with shops, art galleries, environment. You’ll find a few locations listed in Naval, military and maritime history. Some sites the City & Community section in this guide and many more choices date back to the Spanish-American War. Others honor fallen soldiers Airport. One of the most scenic ways to travel to the Kitsap Peninsula eateries and attractions. -

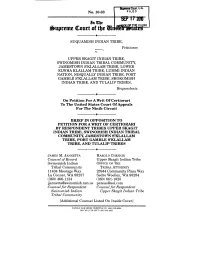

Cert Opp in Suquamish V Upper Skagit Et Al

SUQUAMISH INDIAN TRIBE, Petitioner, v. UPPER SKAGIT INDIAN TRIBE, SWINOMISH INDIAN TRIBAL COMMUNITY, JAMESTOWN S’KLALLAM TRIBE, LOWER ELWHA KLALLAM TRIBE, LUMMI INDIAN NATION, NISQUALLY INDIAN TRIBE, PORT GAMBLE S’KLALLAM TRIBE, SKOKOMISH INDIAN TRIBE, AND TULALIP TRIBES, Respondents. On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI BY RESPONDENT TRIBES UPPER SKAGIT INDIAN TRIBE, SWINOMISH INDIAN TRIBAL COMMUNITY, JAMESTOWN S’KLALLAM TRIBE, PORT GAMBLE S’KLALLAM TRIBE, AND TULALIP TRIBES JAMES M. JANNETTA HAROLD CHESNIN Counsel of Record Upper Skagit Indian Tribe Swinomish Indian OFFICE OF THE Tribal Community TRIBAL ATTORNEY 11404 Moorage Way 25944 Community Plaza Way La Conner, WA 98257 Sedro Woolley, WA 98284 (360) 466-1134 (360) 661-1020 jj [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Respondent Counsel for Respondent Swinomish Indian Upper Skagit Indian Tribe Tribal Community [Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover] COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALl, COLLECT (402) 342-2831 LAUREN P. RASMUSSEN MASON D. MORISSET LAW OFFICES OF MORISSET, SCHLOSSER, LAUREN P. RASMUSSEN JOZW~AK & MCGAW 11904 Third Avenue, 1115 Norton Building Suite 1030 801 Second Avenue Seattle, WA 98101 Seattle, WA 98104 (206) 623-0900 (206) 386-5200 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Respondents Counsel for Respondent Port Gamble S’Klallam Tulalip Tribes and Jamestown S’Klallam Tribes QUESTION PRESENTED In 1975 the district court in United States v. Washington, W.D. Wash. No. C70-9213, a case involv- ing the treaty fishing rights of 21 Indian tribes in northwest Washington, made a factual determination of the Suquamish Tribe’s usual and accustomed fishing places (U&As). -

NATIVE AMERICAN HIGHLIGHTS of WASHINGTON Statepdf

NATIVE AMERICAN HIGHLIGHTS OF WASHINGTON STATE & OLYMPIC NATIONAL PARK (10 day) Fly-Drive Native American culture in the Pacific Northwest is unique and celebrated through the bold art and style of the diverse Northwest Coastal tribes that have been connected to one another for thousands of years through trade. This link is apparent in their art - masks, canoes, totem poles, baskets, clothing and bentwood boxes - using cedar, copper and other materials readily accessible in nature. Their art tells the stories of their lives through the centuries, passing history and wisdom from generation to generation. Native American culture is present in everyday life in Seattle from the totems that grace the parks and public spaces to the manhole covers on the streets. Along your journey, you will experience Seattle’s unique urban attractions, Bellingham’s historic seaport ambiance and the wild beauty of the Olympic Peninsula from lush old-growth forests to spectacular, untamed beaches. En route you’ll encounter the many ways Native American culture is woven into the fabric of the Pacific Northwest. Day 1 Arrive Seattle Pike Place Market 85 Pike Street Seattle, WA 98101 www.pikeplacemarket.org Pike Place Market is a hot spot for fresh food sourced from nearby farms, cocktails created by favorite mixologists and a place to rub elbows with both Seattle locals and visitors. From flying fish to street musicians to gorgeous flowers and an array of delicious food options, this 100+ year-old national historic district is a vibrant neighborhood, welcoming over 10 million visitors annually to this super cool hub. Steinbrueck Native Gallery (Near Pike Place Market) 2030 Western Avenue Seattle, WA 98121 www.steinbruecknativegallery.com Highlights: Works by long- established First Nations masters and talented emerging artists. -

Bibliography for S'abadeb-- the Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian, and Anna Elam, TRC Coordinator

Bibliography for S'abadeb-- The Gifts: Pacific Coast Salish Art and Artists Prepared by Traci Timmons, SAM Librarian, and Anna Elam, TRC Coordinator Books for Adults: the SAM/Dorothy Stimson Bullitt Library Books are available in the Reading Room of the Bullitt Library (Seattle Art Museum, Fifth Floor, South Building). *= books selected for in-gallery reading areas American Indian sculpture: a study of the Northwest coast, by special arrangement with the American Ethnological Society by Wingert, Paul S. (American Indian sculpture: a study of the Northwest coast, by special arrangement with the American Ethnological Society, 1949). E 98 A7 W46 * Aunt Susie Sampson Peter: the wisdom of a Skagit elder by Hilbert, Vi; Miller, Jay et al. (Federal Way, WA: Lushootseed Press, 1995). E 99 S2 P48 Coast Salish essays by Suttles, Wayne P. et al. (Vancouver, BC: Talonbooks; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1987). E 99 S2 S8 The Coast Salish of British Columbia by Barnett, Homer (Eugene: University of Oregon, 1955). E 99 S2 B2 * Contemporary Coast Salish art by Blanchard, Rebecca and Davenport, Nancy. (Seattle: Stonington Gallery : University of Washington Press, 2005). E 99 S2 B6 Crow's shells: artistic basketry of Puget Sound by Marr, Carolyn and Thompson, Nile. (Seattle: Dushuyay Publications, 1983). E 98 B3 T5 * Eyes of Chief Seattle by the Suquamish Museum. (Suquamish, WA: Suquamish Museum, 1985). E 99 S7 S8 * Gram Ruth Sehome Shelton: the wisdom of a Tulalip elder by Hilbert, Vi; Miller, Jay et al. (Federal Way, WA: Lushootseed Press, 1995). E 99 S2 S43 Haboo: Lushootseed literature in English by Hilbert, Vi and Hilbert, Ron.