Visions of Water in Lower Murray Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles and Books About Western and Some of Central Nsw

Rusheen’s Website: www.rusheensweb.com ARTICLES AND BOOKS ABOUT WESTERN AND SOME OF CENTRAL NSW. RUSHEEN CRAIG October 2012. Last updated: 20 March 2013 Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig Using the information from this document: Please note that the research on this web site is freely provided for personal use only. Site users have the author's permission to utilise this information in personal research, but any use of information and/or data in part or in full for republication in any printed or electronic format (regardless of commercial, non-commercial and/or academic purpose) must be attributed in full to Rusheen Craig. All rights reserved by Rusheen Craig. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Wentworth Combined Land Sales Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig 1 Contents THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE WESTERN PLAINS. ...................................................... 6 Exploration of the Bogan. ................................................................................................................................... 6 Roderick Mitchell on the Darling. ...................................................................................................................... 7 Exploration of the Country between the Lachlan and the Darling ...................................................................... 7 Occupation of the Country. ................................................................................................................................ 8 Occupation -

Bound for South Australia Teacher Resource

South Australian Maritime Museum Bound for South Australia Teacher Resource This resource is designed to assist teachers in preparing students for and assessing student learning through the Bound for South Australia digital app. This education resource for schools has been developed through a partnership between DECD Outreach Education, History SA and the South Australian Maritime Museum. Outreach Education is a team of seconded teachers based in public organisations. This app explores the concept of migration and examines the conditions people experienced voyaging to Australia between 1836 and the 1950s. Students complete tasks and record their responses while engaging with objects in the exhibition. This app comprises of 9 learning stations: Advertising Distance and Time Travelling Conditions Medicine at Sea Provisions Sleep Onboard The First 9 Ships Official Return of Passengers Teacher notes in this resource provide additional historical information for the teacher. Additional resources to support student learning about the conditions onboard early migrant ships can be found on the Bound for South Australia website, a resource developed in collaboration with DECD teachers and History SA: www.boundforsouthaustralia.net.au Australian Curriculum Outcomes: Suitability: Students in Years 4 – 6 History Key concepts: Sources, continuity and change, cause and effect, perspectives, empathy and significance. Historical skills: Chronology, terms and Sequence historical people and events concepts Use historical terms and concepts Analysis -

Riverland - Adelaide Timetable

Riverland - Adelaide Timetable MONDAY TO FRIDAY MONDAY TO FRIDAY TO ADELAIDE 973 FROM ADELAIDE 972 am pm RENMARK Visitor Centre 7.30 ADELAIDE Central Bus Station 4.00 Berri Berri Plaza Newsagent 7.50 Elizabeth (P) Bus Stop, Frobisher Road 4.37 Glossop Opp. Glossop Motel 7.57 Gawler (P) Gawler VisitorCentre 4.50 Barmera Barmera Visitor Centre 8.10 Nuriootpa (P) Fire Station 5.15 Cobdogla T/Off near school 8.15 Truro United Roadhouse 5.30 Kingston-on-Murray Store 8.25 Blanchetown - arrive BP Roadhouse 6.00 Waikerie Waikerie Garden Centre 8.50 Blanchetown - depart BP Roadhouse 6.10 Blanchetown - arrive BP Roadhouse 9.20 Waikerie Waikerie Garden Centre 6.40 Blanchetown - depart BP Roadhouse 9.30 Kingston-on-Murray Store 7.10 Truro Opp. United Roadhouse 10.00 Cobdogla Turn off near school 7.15 Nuriootpa (S) Opp. Fire Station 10.15 Barmera Barmera Visitor Centre 7.20 Gawler (S) Gawler Visitor Centre 10.38 Glossop Glossop Motel 7.33 Elizabeth (S) Bus Stop, Frobisher Road 10.53 Berri Berri Plaza Newagent 7.40 ADELAIDE Central Bus Station 11.30 RENMARK Visitor Centre 8.00 Long Weekend and Public Holiday periods (including the day before and the day after) - check for special timetables with your local agent or Stateliner, unless booking online which will include all alterations. On Request Denotes via turn off (S) Set-down only (P) Pick-up only All times subject to traffic and road conditions Refer to General Information for important travel details 30/06/20 AGENTS BLANCHETOWN BP Blanchetown (08) 8540 5060 WAIKERIE Waikerie Garden Centre (08) 8541 3759 KINGSTON-ON-MURRAY General Store (08) 8583 0220 BERRI Berri Plaza Newsagent & Photographics (08) 8582 2575 RENMARK Stateliner Office - Adelaide 1300 851 345 GENERAL INFORMATION RESERVATIONS Please book at least 48 hours in advance. -

Upper Riccarton Cemetery 2007 1

St Peter’s, Upper Riccarton, is the graveyard of owners and trainers of the great horses of the racing and trotting worlds. People buried here have been in charge of horses which have won the A. J. C. Derby, the V.R.C. Derby, the Oaks, Melbourne Cup, Cox Plate, Auckland Cup (both codes), New Zealand Cup (both codes) and Wellington Cup. Area 1 Row A Robert John Witty. Robert John Witty (‘Peter’ to his friends) was born in Nelson in 1913 and attended Christchurch Boys’ High School, College House and Canterbury College. Ordained priest in 1940, he was Vicar of New Brighton, St. Luke’s and Lyttelton. He reached the position of Archdeacon. Director of the British Sailors’ Society from 1945 till his death, he was, in 1976, awarded the Queen’s Service Medal for his work with seamen. Unofficial exorcist of the Anglican Diocese of Christchurch, Witty did not look for customers; rather they found him. He said of one Catholic lady: “Her priest put her on to me; they have a habit of doing that”. Problems included poltergeists, shuffling sounds, knockings, tapping, steps tramping up and down stairways and corridors, pictures turning to face the wall, cold patches of air and draughts. Witty heard the ringing of Victorian bells - which no longer existed - in the hallway of St. Luke’s vicarage. He thought that the bells were rung by the shade of the Rev. Arthur Lingard who came home to die at the vicarage then occupied by his parents, Eleanor and Archdeacon Edward Atherton Lingard. In fact, Arthur was moved to Miss Stronach’s private hospital where he died on 23 December 1899. -

November 2019

Care Resilience Create Optimism Innovate Courage UHSnews Knowledge ISSUE: 7| TERM FOUR 2019 Inside this issue From our Principal, Mr David Harriss End of year Information Hello everyone, and welcome to our second-last newsletter for the year. Year 12 Exams are 2 Year 12 Graduation finished, all work has been submitted and our 2019 cohort can now relax and await their 4 final results just before Christmas. A final year 12 report will be coming home soon based School Sport 10 on school-based results. These grades will go through a standards moderation process and Mathematical Mindsets may be altered by the SACE Board, and their Externally Marked work (Exams, Investigations 11 etc.) needs to be added as well. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all of these Student Voice 16 students and their families for their contribution to Underdale High School and wish them Dental Program all the best in whatever endeavours they wish to pursue in the future. 19 Calendar Dates Plans for our $20million development are nearing completion, and some of these plans and images will be on our Website soon. I will let you know when this happens. It is envisaged Term 4 that building will start in the second half of next year and be completed by the end of 2021, Week 6 in readiness for the Year 7’s coming to Underdale High School. We are excited by both of these events, and they promise to build on our great school community. Wednesday 20th November - Year 12 Formal The last weeks of school are vital for our remaining students. -

Galahs This Is the Longer Version of an Article to Be Published in Australian Historical Studies in April 2010. Copyright Bill

Galahs This is the longer version of an article to be published in Australian Historical Studies in April 2010. Copyright Bill Gammage, 3 November 2008. Email [email protected] When Europeans arrived in Australia, galahs were typically inland birds, quite sparsely distributed. Now they range from coast to coast, and are common. Why did this change occur? Why didn’t it occur earlier? Galahs feed on the ground. They found Australia’s dominant inland grasses too tall to get at the seed, so relied on an agency to shorten them: Aboriginal grain cropping before contact, introduced stock after it. *** On 3 July 1817, near the swamps filtering the Lachlan to the Murrumbidgee and further inland than any white person had been, John Oxley wrote, ‘Several flocks of a new description of pigeon were seen for the first time... A new species of cockatoo or paroquet, being between both, was also seen, with red necks and breasts, and grey backs. I mention these birds particularly, as they are the only ones we have yet seen which at all differ from those known on the east coast’ [1]. Allan Cunningham, Oxley’s botanist, also saw the birds. ‘We shot a brace of pigeons of a new species...’, he noted, ‘Some other strange birds were observed (supposed to be Parrots), about the size and flight of a pigeon, with beautiful red breasts’, and next morning, ‘They are of a light ash colour on the back and wings, and have rich pink breasts and heads’ [1]. In the manner of science parrot and pigeon were shot, and within a few months John Lewin in Sydney drew the first known depictions of them [53]. -

The Riverland Regional Fact Sheet

The Riverland Overview The Riverland includes about It is a critical spiritual and cultural 3 million hectares — around 3% of the location for First Nations of the River Murray–Darling Basin. Murray and Mallee Region. The Riverland Ramsar wetlands run Water-based activities and recreation from the South Australian border to focussed on the River Murray and Renmark, include the Chowilla, Pike dryland conservation reserves are and Katarapko foodplains and are important tourism drawcards. home to a wide range of waterbirds, plants and aquatic species. The River Murray provides water to Adelaide and regional towns, from Agriculture includes irrigated and the Eyre Peninsula to the South East dryland crop production, including of the state. intensive horticulture, cereal cropping and grazing. Image: The River Murray near Renmark, South Australia Carnarvon N.P. r e v i r e R iv e R v i o g N re r r e a v i W R o l g n Augathella a L r e v i R d r a W Chesterton Range N.P. Charleville Mitchell Morven Roma Cheepie Miles River Chinchilla amine Cond Condamine k e e r r ve C i R l M e a nn a h lo Dalby c r a Surat a B e n e o B a Wyandra R Tara i v e r QUEENSLAND Brisbane Toowoomba Moonie Thrushton er National e Riv ooni Park M k Beardmore Reservoir Millmerran e r e ve r i R C ir e e St George W n i Allora b e Bollon N r e Jack Taylor Weir iv R Cunnamulla e n n N lo k a e B Warwick e r C Inglewood a l a l l a g n u Coolmunda Reservoir M N acintyre River Goondiwindi 25 Dirranbandi M Stanthorpe 0 50 Currawinya N.P. -

2006 007.Pdf

No. 7 383 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 2 FEBRUARY 2006 CONTENTS Page Page Appointments, Resignations, Etc...............................................384 Proclamations ............................................................................ 419 Architects Act 1939—Register..................................................385 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................... 438 Corporations and District Councils—Notices............................434 Rail Safety Act 1996—Notice................................................... 417 Development Act 1993—Notices..............................................395 Electoral Act 1985—Notice ......................................................410 REGULATIONS Environment Protection Act 1993—Notice...............................405 Summary Offences Act 1953 (No. 16 of 2006) ..................... 420 Fisheries Act 1982—Notice ......................................................410 Senior Secondary Assessment Board of South Harbors and Navigation Regulations 1994—Notice..................410 Australia Act 1983 (No. 17 of 2006).................................. 422 Land and Business (Sale and Conveyancing) Act 1994— Natural Resources Management Act 2004 Notice ....................................................................................410 (No. 18 of 2006)................................................................ -

For GRG 24/90 Miscellaneous Records of Historical Interest

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRG 24/90 Miscellaneous records of historical interest, artificial series - Colonial Secretary's Office, Governor's Office and others Series This series consists of miscellaneous records from Description various government agencies, namely the Colonial Secretary's Office and the Governor's Office, from 1837 - 1963. Records include correspondence between the Governor and the Colonial Secretary, correspondence between the Governor and Cabinet, and correspondence of the Executive Council. Also includes records about: hospitals, gaols, cemeteries, courts, the Surveyor-General's Office, harbours, Botanic Gardens, Lunatic Asylum, Destitute Board, exploration, police and military matters, Chinese immigration, Aboriginal people, marriage licences, prostitution, the postal service, the Adelaide Railway Company, agriculture, churches, and the Admella sinking. The items in this artificial series were allocated a number by State Records. Series date range 1837 - 1963 Agencies Office of the Governor of South Australia and responsible Department of the Premier and Cabinet Access Open. Determination Contents Arranged alphabetically by topic. A - Y State Records has public access copies of this correspondence on microfilm in our Research Centre. 27 May 2016 INDEX TO GRG 24/90, MISCELLANEOUS RECORDS SUBJECT DESCRIPTION REFERENCE NO. ABERNETHY, J. File relating to application GRG 24/90/86 by J. Abernethy, of Wallaroo Bay, for a licence for an oyster bed. Contains letter from J.B. Shepherdson J.P., together with a chart of the bed. 24 April, 1862. ABORIGINES Report by M. Moorhouse on GRG 24/90/393 O'Halloran's expedition to the Rufus. -

Aboriginal/ European Interactions and Frontier Violence on the Western

the space of conflict: Aboriginal/ European interactions and frontier violence on the western Central murray, south Australia, 1830–41 Heather Burke, Amy Roberts, Mick Morrison, Vanessa Sullivan and the River Murray and Mallee Aboriginal Corporation (RMMAC) Colonialism was a violent endeavour. Bound up with the construction of a market-driven, capitalist system via the tendrils of Empire, it was intimately associated with the processes of colonisation and the experiences of exploiting the land, labour and resources of the New World.1 All too often this led to conflict, particularly between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Overt violence (the euphemistic ‘skirmishes’, ‘affrays’ and ‘collisions’ of the documentary record), clandestine violence (poisonings, forced removals, sexual exploitation and disease) and structural violence (the compartmentalisation of Aboriginal people through processes of race, governance and labour) became routinised aspects of colonialism, buttressed by structures of power, inequality, dispossession and racism. Conflict at the geographical margins of this system was made possible by the general anxieties of life at, or beyond, the boundaries of settlement, closely associated with the normalised violence attached to ideals of ‘manliness’ on the frontier.2 The ‘History Wars’ that ignited at the turn of the twenty-first century sparked an enormous volume of detailed research into the nature and scale of frontier violence across Australia. Individual studies have successfully canvassed the 1 Silliman 2005. 2 -

A Biological Survey of the Murray Mallee South Australia

A BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE MURRAY MALLEE SOUTH AUSTRALIA Editors J. N. Foulkes J. S. Gillen Biological Survey and Research Section Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia 2000 The Biological Survey of the Murray Mallee, South Australia was carried out with the assistance of funds made available by the Commonwealth of Australia under the National Estate Grants Programs and the State Government of South Australia. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Australian Heritage Commission or the State Government of South Australia. This report may be cited as: Foulkes, J. N. and Gillen, J. S. (Eds.) (2000). A Biological Survey of the Murray Mallee, South Australia (Biological Survey and Research, Department for Environment and Heritage and Geographic Analysis and Research Unit, Department for Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts). Copies of the report may be accessed in the library: Environment Australia Department for Human Services, Housing, GPO Box 636 or Environment and Planning Library CANBERRA ACT 2601 1st Floor, Roma Mitchell House 136 North Terrace, ADELAIDE SA 5000 EDITORS J. N. Foulkes and J. S. Gillen Biological Survey and Research Section, Heritage and Biodiversity Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 AUTHORS D. M. Armstrong, J. N. Foulkes, Biological Survey and Research Section, Heritage and Biodiversity Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001. S. Carruthers, F. Smith, S. Kinnear, Geographic Analysis and Research Unit, Planning SA, Department for Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, GPO Box 1815, ADELAIDE SA 5001. -

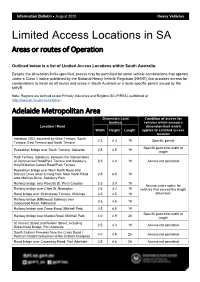

Consolidated Table of Limited Access Locations for SA

Information Bulletin August 2020 Heavy Vehicles Limited Access Locations in SA Areas or routes of Operation Outlined below is a list of Limited Access Locations within South Australia. Despite the dimension limits specified, access may be permitted for some vehicle combinations that operate under a Class 1 notice published by the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator (NHVR) that provides access for combinations to travel on all routes and areas in South Australia or a route specific permit issued by the NHVR. Note: Regions are defined as per Primary Industries and Regions SA (PIRSA), published at http://www.pir.sa.gov.au/regions. Adelaide Metropolitan Area Dimension Limit Condition of access for (metres) vehicles which exceed a Location / Road dimension limit which Width Height Length applies to a limited access location Adelaide CBD, bounded by West Terrace, South 2.5 4.3 19 Specific permit Terrace, East Terrace and North Terrace Specific permit for width or Pedestrian bridge over South Terrace, Adelaide 2.5 4.5 19 length Park Terrace, Salisbury, between the intersections of Commercial Road/Park Terrace and Salisbury 2.5 4.3 19 Access not permitted Hwy/Waterloo Corner Road/Park Terrace Pedestrian bridge over Main North Road and Malinya Drive when turning from Main North Road 3.5 4.5 19 onto Malinya Drive, Salisbury Park Railway bridge over Rosetta St, West Croydon 2.5 3.0 19 Access under notice for Railway bridge over Chief St, Brompton 2.5 3.2 19 vehicles that exceed the length Road bridge over St Andrews Terrace, Willunga 3.5 4.5 19 dimension