'Garra Charrua' the Unlikely Success of Uruguayan Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GURU'guay GUIDE to URUGUAY Beaches, Ranches

The Guru’Guay Guide to Beaches, Uruguay: Ranches and Wine Country Uruguay is still an off-the-radar destination in South America. Lucky you Praise for The Guru'Guay Guides The GURU'GUAY GUIDE TO URUGUAY Beaches, ranches Karen A Higgs and wine country Karen A Higgs Copyright © 2017 by Karen A Higgs ISBN-13: 978-1978250321 The All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever Guru'Guay Guide to without the express written permission of the publisher Uruguay except for the use of brief quotations. Guru'Guay Productions Beaches, Ranches Montevideo, Uruguay & Wine Country Cover illustrations: Matias Bervejillo FEEL THE LOVE K aren A Higgs The Guru’Guay website and guides are an independent initiative Thanks for buying this book and sharing the love 20 18 Got a question? Write to [email protected] www.guruguay.com Copyright © 2017 by Karen A Higgs ISBN-13: 978-1978250321 The All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever Guru'Guay Guide to without the express written permission of the publisher Uruguay except for the use of brief quotations. Guru'Guay Productions Beaches, Ranches Montevideo, Uruguay & Wine Country Cover illustrations: Matias Bervejillo FEEL THE LOVE K aren A Higgs The Guru’Guay website and guides are an independent initiative Thanks for buying this book and sharing the love 20 18 Got a question? Write to [email protected] www.guruguay.com To Sally Higgs, who has enjoyed beaches in the Caribbean, Goa, Thailand and on the River Plate I started Guru'Guay because travellers complained it was virtually impossible to find a good guidebook on Uruguay. -

Los Frentes Del Anticomunismo. Las Derechas En

Los frentes del anticomunismo Las derechas en el Uruguay de los tempranos sesenta Magdalena Broquetas El fin de un modelo y las primeras repercusiones de la crisis Hacia mediados de los años cincuenta del siglo XX comenzó a revertirse la relativa prosperidad económica que Uruguay venía atravesando desde el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A partir de 1955 se hicieron evidentes las fracturas del modelo proteccionista y dirigista, ensayado por los gobiernos que se sucedieron desde mediados de la década de 1940. Los efectos de la crisis económica y del estancamiento productivo repercutieron en una sociedad que, en la última década, había alcanzado una mejora en las condiciones de vida y en el poder adquisitivo de parte de los sectores asalariados y las capas medias y había asistido a la consolidación de un nueva clase trabajadora con gran capacidad de movilización y poder de presión. El descontento social generalizado tuvo su expresión electoral en las elecciones nacionales de noviembre de 1958, en las que el sector herrerista del Partido Nacional, aliado a la Liga Federal de Acción Ruralista, obtuvo, por primera vez en el siglo XX, la mayoría de los sufragios. Con estos resultados se inauguraba el período de los “colegiados blancos” (1959-1966) en el que se produjeron cambios significativos en la conducción económica y en la concepción de las funciones del Estado. La apuesta a la liberalización de la economía inauguró una década que, en su primera mitad, se caracterizó por la profundización de la crisis económica, una intensa movilización social y la reconfiguración de alianzas en el mapa político partidario. -

Holland America's Shore Excursion Brochure

Continental Capers Travel and Cruises ms Westerdam November 27, 2020 shore excursions Page 1 of 51 Welcome to Explorations Central™ Why book your shore excursions with Holland America Line? Experts in Each Destination n Working with local tour operators, we have carefully curated a collection of enriching adventures. These offer in-depth travel for first- Which Shore Excursions Are Right for You? timers and immersive experiences for seasoned Choose the tours that interest you by using the icons as a general guide to the level of activity alumni. involved, and select the tours best suited to your physical capabilities. These icons will help you to interpret this brochure. Seamless Travel Easy Activity: Very light activity including short distances to walk; may include some steps. n Pre-cruise, on board the ship, and after your cruise, you are in the best of hands. With the assistance Moderate Activity: Requires intermittent effort throughout, including walking medium distances over uneven surfaces and/or steps. of our dedicated call center, the attention of our Strenuous Activity: Requires active participation, walking long distances over uneven and steep terrain or on on-board team, and trustworthy service at every steps. In certain instances, paddling or other non-walking activity is required and guests must be able to stage of your journey, you can truly travel without participate without discomfort or difficulty breathing. a care. Panoramic Tours: Specially designed for guests who enjoy a slower pace, these tourss offer sightseeing mainly from the transportation vehicle, with few or no stops, and no mandatory disembarkation from the vehicle Our Best Price Guarantee during the tour. -

Uruguay: an Overview

May 8, 2018 Uruguay: An Overview Uruguay, a small nation of 3.4 million people, is located on Figure 1.Uruguay at a Glance the Atlantic coast of South America between Brazil and Argentina. The country stands out in Latin America for its strong democratic institutions; high per capita income; and low levels of corruption, poverty, and inequality. As a result of its domestic success and commitment to international engagement, Uruguay plays a more influential role in global affairs than its size might suggest. Successive U.S. administrations have sought to work with Uruguay to address political and security challenges in the Western Hemisphere and around the world. Political and Economic Situation Uruguay has a long democratic tradition but experienced 12 years of authoritarian rule following a 1973 coup. During the dictatorship, tens of thousands of Uruguayans were Sources: CRS Graphics, Instituto Nacional de Estadística de forced into political exile; 3,000-4,000 were imprisoned; Uruguay, Pew Research Center, and the International Monetary Fund. and several hundred were killed or “disappeared.” The country restored civilian democratic governance in 1985, The Broad Front also has enacted several far-reaching and analysts now consider Uruguay to be among the social policy reforms, some of which have been strongest democracies in the world. controversial domestically. The coalition has positioned Uruguay on the leading edge of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and President Tabaré Vázquez of the center-left Broad Front transgender (LGBT) rights in Latin America by allowing was inaugurated to a five-year term in March 2015. This is LGBT individuals to serve openly in the military, legalizing his second term in office—he previously served as adoption by same-sex couples, allowing individuals to president from 2005 to 2010—and the third consecutive change official documents to reflect their gender identities, term in which the Broad Front holds the presidency and and legalizing same-sex marriage. -

INTELLECTUALS and POLITICS in the URUGUAYAN CRISIS, 1960-1973 This Thesis Is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements

INTELLECTUALS AND POLITICS IN THE URUGUAYAN CRISIS, 1960-1973 This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Spanish and Latin American Studies at the University of New South Wales 1998 And when words are felt to be deceptive, only violence remains. We are on its threshold. We belong, then, to a generation which experiences Uruguay itself as a problem, which does not accept what has already been done and which, alienated from the usual saving rituals, has been compelled to radically ask itself: What the hell is all this? Alberto Methol Ferré [1958] ‘There’s nothing like Uruguay’ was one politician and journalist’s favourite catchphrase. It started out as the pride and joy of a vision of the nation and ended up as the advertising jingle for a brand of cooking oil. Sic transit gloria mundi. Carlos Martínez Moreno [1971] In this exercise of critical analysis with no available space to create a distance between living and thinking, between the duties of civic involvement and the will towards lucidity and objectivity, the dangers of confusing reality and desire, forecast and hope, are enormous. How can one deny it? However, there are also facts. Carlos Real de Azúa [1971] i Acknowledgments ii Note on references in footnotes and bibliography iii Preface iv Introduction: Intellectuals, Politics and an Unanswered Question about Uruguay 1 PART ONE - NATION AND DIALOGUE: WRITERS, ESSAYS AND THE READING PUBLIC 22 Chapter One: The Writer, the Book and the Nation in Uruguay, 1960-1973 -

Ilson Y Los Tupamaros

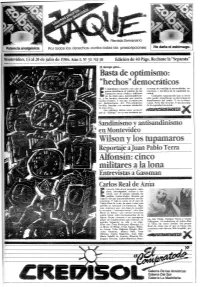

.Revista Semanario Por todos los derechos, contra todas las proscripciones . No daña el estómago. 13 al20 de julio de 1984. Año l. No 31 N$ 30 Edición de 40 Págs. Reclame la "Separata" El tiempo pasa ... Basta de optimismo: "hechos'' democráticos 1 .optimismo excesivo con que al ra tratar de conciliar la inconciliable: de gunos abordaron el reinicio de los mocracia y doctrina de la seguridad na contactos entre civiles y militares cional. no ha dado paso, lamentablemen Cualquier negociación' que se inicie te, a los hechos concretos que nuestra sólo puede desembocar en las formas de nación reclama. Y eso que, a estarse por transferencia del poder. Y en la demo las declaraciones del Vice-Almirante cracia. Neto. Sin recortes. Y sin doctrina Invidio, bastaba con sentarse ·alrededor de la seguridad nacional. de una mesa ... Los militares deben tener presente que el "diálogo" no es una instancia pa- Sandinisffio y antisandinismo en Montevideo ilson y los tupamaros Reportaje a Juan Pablo Tet·t·a Alfonsín: cinco militares a la lona Entrevistas a Gassman Carlos Real de Azúa vocar la vida de un pensador, ensa yista, investigador, crítico y do cente, por el propio cúmulo de Eperfiles intelectuales, llevaría un espacio del que lamentablemente no dis ponemos. Y más si, como en el caso de Carlos Real de Azúa, de entre todos esos perfiles se destacan los humanos. Diga mos en ton ces que, sin dejar de a ten!ler. la aversión ·-"aversión severa", dice Lisa Block de Behar- que nuestro ensayista sentía hacia toda representación de su figura, Jaque convoca a un prestigioso grupo de colaboradores para esbozar, en no, Ida Vitale, !Enrique Fierro y Carlos nuestra Separata, su vida y su obra. -

Redalyc.SOCIAL PROBLEMS: the DEMOGRAPHIC EMERGENCY IN

JANUS.NET, e-journal of International Relations E-ISSN: 1647-7251 [email protected] Observatório de Relações Exteriores Portugal Delisante Morató, Virginia SOCIAL PROBLEMS: THE DEMOGRAPHIC EMERGENCY IN URUGUAY JANUS.NET, e-journal of International Relations, vol. 6, núm. 1, mayo-octubre, 2015, pp. 68-85 Observatório de Relações Exteriores Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=413541154005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative OBSERVARE Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa ISSN: 1647-7251 Vol. 6, n.º 1 (May-October 2015), pp. 68-85 SOCIAL PROBLEMS: THE DEMOGRAPHIC EMERGENCY IN URUGUAY Virginia Delisante Morató [email protected] Holder of a Master Degree in International Relations from ISCSP, University of Lisbon Holder of a Bachelor Degree in International Studies from Universidad ORT Uruguay. Deputy Academic Coordinator of the Bachelor Degree in International Studies, Lecturer and Associate Professor of Final Projects of the Faculty of Management and Social Sciences of the University ORT Uruguay. Abstract This article focuses on Uruguay in a context of highly publicized external image through its recent former president Jose Mujica. It covers government policies related to the problems that all societies must face, addressing, in particularly, the demographic problem it is experiencing, since it differentiates the country both in a regional and in the entire Latin American context. Keywords: Uruguay; social problems; demography: emigration How to cite this article Morató, Virginia Delisante (2015). -

The United States and the Uruguayan Cold War, 1963-1976

ABSTRACT SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 In the early 1960s, Uruguay was a beacon of democracy in the Americas. Ten years later, repression and torture were everyday occurrences and by 1973, a military dictatorship had taken power. The unexpected descent into dictatorship is the subject of this thesis. By analyzing US government documents, many of which have been recently declassified, I examine the role of the US government in funding, training, and supporting the Uruguayan repressive apparatus during these trying years. Matthew Ford May 2015 SUBVERTING DEMOCRACY, PRODUCING TERROR: THE UNITED STATES AND THE URUGUAYAN COLD WAR, 1963-1976 by Matthew Ford A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno May 2015 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Matthew Ford Thesis Author Maria Lopes (Chair) History William Skuban History Lori Clune History For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. Permission to reproduce this thesis in part or in its entirety must be obtained from me. -

Uruguay Year 2020

Uruguay Year 2020 1 SENSITIVE BUT UNCLASSIFIED Table of Contents Doing Business in Uruguay ____________________________________________ 4 Market Overview ______________________________________________________________ 4 Market Challenges ____________________________________________________________ 5 Market Opportunities __________________________________________________________ 5 Market Entry Strategy _________________________________________________________ 5 Leading Sectors for U.S. Exports and Investment __________________________ 7 IT – Computer Hardware and Telecommunication Equipment ________________________ 7 Renewable Energy ____________________________________________________________ 8 Agricultural Equipment _______________________________________________________ 10 Pharmaceutical and Life Science _______________________________________________ 12 Infrastructure Projects________________________________________________________ 14 Security Equipment __________________________________________________________ 15 Customs, Regulations and Standards ___________________________________ 17 Trade Barriers _______________________________________________________________ 17 Import Tariffs _______________________________________________________________ 17 Import Requirements and Documentation _______________________________________ 17 Labeling and Marking Requirements ____________________________________________ 17 U.S. Export Controls _________________________________________________________ 18 Temporary Entry ____________________________________________________________ -

Montevideo, Uruguay, 2 - 3 October 2019

Report on the IX Reflection Forum 2019 “Building inclusive societies under the new development paradigm” Montevideo, Uruguay, 2 - 3 October 2019 Executive Summary On 2 and 3 October 2019 the IX EU-LAC Reflection Forum took place in Montevideo (Uruguay), jointly organised by the Uruguayan Agency for International Cooperation (AUCI), the Uruguayan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean of the United Nations (ECLAC), the EUROsociAL+ Programme and the Ibero-American General Secretariat (SEGIB). In accordance with its mandate to promote debate on matters of priority to the EU-LAC Strategic Association and to encourage contributions to the inter-governmental process from the economic and academic sectors and other sectors of civil society, the EU-LAC Foundation regularly organises Reflection Forums in its member states. The specific objectives of the Reflection Forums are: (i) to provide an informal platform for discussion between officials and academic experts and other sectors of civil society, concerning EU-LAC relations, (ii) to discuss progress made and challenges encountered in bi-regional relations and (iii) to feed into analyses with fresh perceptions, as well as to make recommendations for action. Discussions in the Reflection Forums take place under “Chatham House” rules, and the format attempts to generate an atmosphere of respect and mutual trust, thus facilitating the open and informal exchange of points of view and perspectives between the participants, in a truly bi-regional approach. The specific topic of the IX Reflection Forum was: “Building inclusive societies under the new development paradigm”. -

LOS TUPAMAROS Continuadores Históricos Del Ideario Artiguista

Melba Píriz y Cristina Dubra (1997c) LOS TUPAMAROS Continuadores históricos del ideario artiguista Considerado el territorio de la Banda Oriental como "tierra sin ningún provecho" por los conquistadores españoles, su conquista será tardía y este hecho signará la historia de esta fértil pradera, habitada desde ya mucho tiempo (estudios recientes nos llevan a considerar en miles de años la presencia de los primeros pobladores en la región) por comunidades indígenas en algunos casos cultivadores y, o cazadores, pescadores y recolectores .La situación de frontera interimperial (conflicto de límites entre los dominios de España y Portugal) determinará el interés por estos territorios pese a la sociedad indígena indómita que la habitaba. En el siglo XVII, la introducción del ganado bovino pautará de aquí en más la economía y la sociedad de esta Banda. La primera forma de explotación de la riqueza pecuaria fue la vaquería, expedición para matar ganado, extraer el cuero y el sebo. La vaquería depredó el ganado "cimarrón", por eso se irá sustituyendo este sistema por "la estancia", establecimiento permanente con ocupación de tierra. El poblamiento urbano fue también una consecuencia del carácter fronterizo de nuestro territorio. En 1680 los portugueses fundan la Colonia del Sacramento y a partir de 1724 los españoles fundan Montevideo. Durante el coloniaje estará presente un gran conflicto entre los grandes latifundistas por un lado y los pequeños y medianos hacendados por otro A comienzos del siglo XIX, se producen las invasiones inglesas al Río de la Plata. La ocupación que realizaron si bien breve, no dejará de tener importancia. Se agudizaron, por ejemplo, las contradicciones ya existentes en la sociedad colonial y comenzó a hacerse inminente la lucha por el poder entre una minoría española residente encabezada por los grandes comerciantes monopolistas y los dirigentes del grupo criollo, hijos de españoles nacidos en América. -

El Artiguismo Y El Movimiento De Liberación Nacional TUPAMAROS

El Artiguismo y el Movimiento de Liberación Nacional TUPAMAROS [Este ha sido escrito e impreso en mimeografo de forma clandestina en octubre del año 1975] Autoría: anónima mln-tupamaros.org. uy PREFACIO Ante la conmemoración de un nuevo natalicio de José Artigas, hemos decidido homenajearlo publicando y sacando a la luz un libro con valor histórico (tanto por su forma, contenido, como contexto histórico en el que fue producido). El M.L.N.-Tupamaros se considera desde sus inicios como continuadores de la lucha iniciada por el artiguismo y es en este sentido, sin entrar en detalles del contenido de la publicación, que decidimos realizar este aporte como forma de hacer público este valioso aporte escrito de forma anónima. Éste ha sido escrito e impreso en mimeógrafo de forma clandestina en octubre del año 1975 y confirma que el M.L.N.-T en ese período no se encontraba totalmente en prisión o en el exilio. Hemos sido fieles al original en su totalidad (ilustraciones y textos) y es un aporte en la intención de recuperar parte de la "historia reciente” y de la lucha de nuestro pueblo. Montevideo, 19 de junio de 2020 Tupamaros El ARTIGUISMO Y El MOVIMIENTO DE LIBERACIÓN NACIONAL (TUPAMAROS) OCTUBRE 1975 ................................................................................ P ig . 3 ir ll|ti y la lucha del lCLlf(T)...............•»••••• ............................. * 3 Bacca ccoodolcaa da la Bevo lue lí o ¿ rtlg u le ta ............................• • 11 Z) Bacca too ohmica* del fc C tr a h ia c ..« * ..« » * ......................... • 17 l) Banca fielest y humanae dal vocali eoo provincial.» • 17 I Buenos Airea» la p ro vin e la -p u e rio *..................................