Review of Yellow Sky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

Stephen Crane on Film: Adaptation As

STEPHEN CRANE ON FILM: ADAPTATION AS INTERPRETATION By JANET BUCK ROLLINS r Bachelor of Arts Southern Oregon State College Ashland, Oregon 1977 Master of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1979 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for· the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1983 LIBRARY~ ~ STEPHEN CRANE ON FILM: ADAPTATION AS INTERPRETATION Thesis Approved: ii . ~ 1168780 ' PREFACE Criticism of film adaptations based on Stephen Crane's fiction is for the most part limited to superficial reviews or misguided articles. Scholars have failed to assess cinematic achievements or the potential of adaptations as interpretive tools. This study will be the first to gauge the success of the five films attempting to recreate and inter pret Crane's vision. I gratefully acknowledge the benefic criticism of Dr. Gordon Weaver, Dr. Jeffrey Walker, and Dr. William Rugg. Each scholar has provided thoughtful direction in content, organization, and style. I am espe cially appreciative of the prompt reading and meticulous, constructive comments of Dr. Leonard J. Leff. Mr. Terry Basford and Mr. Kim Fisher of the Oklahoma State Univer sity library deserve thanks for encouraging and aiding the research process. My husband, Peter, provided invaluable inspiration, listened attentively, and patiently endured the many months of long working hours. Finally, I dedicate this study to my parents and to my Aunt, Florence & Fuller. Their emotional and financial support have made my career as a scholar both possible and rewarding. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FILM MEETS CRANE'S ART 14 III. -

Forbidden Planet: Film Score for Full Orchestra

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 12-2003 Forbidden Planet: Film Score for Full Orchestra Tim Perrine Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Perrine, Tim, "Forbidden Planet: Film Score for Full Orchestra" (2003). Graduate Thesis Collection. 400. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/400 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Name of candidate: (111f:£tz£Zt8\lf:.- ····························································································· Oral examination: Date ..................... l.. ? ....... 1J?.g~.~.?.~.~ ..... ?:gO 3 Committee: Thesis title: .......... f .. O..~.~. .LP..P.f .. N. ......1?.~~g.) ······················'91 () (6"~$f:F,._ ............. · Thesis approved in final form: Date ................ }..fJ... ..... P.£..~.J?~...... '?:PP.~ ........ Major Professor .. ........ ........ z.{;:.f:VF.~f.f?.- STRANGE PLANET ~ FAMILIAR SOUNDS RE-SCORING FORBIDDEN PLANET Tim Perrine, 2003 Master,s Thesis Paper Prologue The intent of my master's thesis is two-fold. First, I wanted to present a large- scale work for orchestra that showcased the skills and craft I have developed as a composer (and orchestrator) to date. Secondly, since my goal as a composer is to work in Hollywood as a film composer, I wanted my large-scale work to function as a film score, providing the emotional backbone and highlighting action for a major motion picture. In order to achieve this, I needed a film that was both larger-than-life and contained, in my opinion, an easily replaceable score (or no score at all). -

Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction

“Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction By Dr. John L. Flynn While most critics tend to regard “Forbidden Planet” (1956) as a futuristic retelling of William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”—with Morbius as Prospero, Robby the Robot as Arial, and the Id monster as the evil Caliban—this very conventional approach overlooks the most obvious. “Forbidden Planet” was, in fact, pulp science fiction, a conglomeration of every cliché and melodramatic element from the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s. With its mysterious setting on an alien world, its stalwart captain and blaster-toting crew, its mad scientist and his naïve yet beautiful daughter, its indispensable robot, and its invisible monster, the movie relied on a proven formula. But even though director Fred Wilcox and scenarist Cyril Hume created it on a production line to compete with the other films of its day, “Forbidden Planet” managed to transcend its pulp origins to become something truly memorable. Today, it is regarded as one of the best films of the Fifties, and is a wonderful counterpoint to Robert Wise’s “The Day the Earth Stood Still”(1951). The Golden Age of Science Fiction is generally recognized as a twenty-year period between 1926 and 1946 when a handful of writers, including Clifford Simak, Jack Williamson, Isaac Asimov, John W. Campbell, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Frederick Pohl, and L. Ron Hubbard, were publishing highly original, science fiction stories in pulp magazines. While the form of the first pulp magazine actually dates back to 1896, when Frank A. Munsey created The Argosy, it wasn’t until 1926 when Hugo Gernsback published the first issue of Amazing Stories that science fiction had its very own forum. -

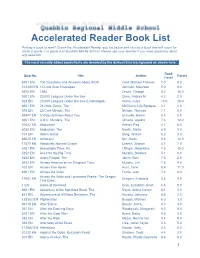

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

+- Vimeo Link for ALL of Bruce Jackson's and Diane

Virtual February 9, 2021 (42:2) William A. Wellman: THE PUBLIC ENEMY (1931, 83 min) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries +- Vimeo link for ALL of Bruce Jackson’s and Diane Christian’s film introductions and post-film discussions in the Spring 2021 BFS Vimeo link for our introduction to The Public Enemy Zoom link for all Fall 2020 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post-screening discussions: Meeting ID: 925 3527 4384 Passcode: 820766 Selected for National Film Registry 1998 Directed by William A. Wellman Written by Kubec Glasmon and John Bright Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck which are 1958 Lafayette Escadrille, 1955 Blood Cinematography by Devereaux Jennings Alley, 1954 Track of the Cat, 1954 The High and the Film Editing by Edward M. McDermott Mighty, 1953 Island in the Sky, 1951 Westward the Makeup Department Perc Westmore Women, 1951 It's a Big Country, 1951 Across the Wide Missouri, 1949 Battleground, 1948 Yellow Sky, James Cagney... Tom Powers 1948 The Iron Curtain, 1947 Magic Town, 1945 Story Jean Harlow... Gwen Allen of G.I. Joe, 1945 This Man's Navy, 1944 Buffalo Bill, Edward Woods... Matt Doyle 1943 The Ox-Bow Incident, 1939 The Light That Joan Blondell... Mamie Failed, 1939 Beau Geste, 1938 Men with Wings, 1937 Donald Cook... Mike Powers Nothing Sacred, 1937 A Star Is Born, 1936 Tarzan Leslie Fenton... Nails Nathan Escapes, 1936 Small Town Girl, 1936 Robin Hood of Beryl Mercer.. -

Forbidden Planet Was Nomi- Nated for an Oscar® (Special Effects) and Is Presented in Cinemascope with Color by Deluxe

Alex Film Society presents FORBIDDEN Saturday, July 7, 2007 PLANEt 2 pm & 8 pm Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1956) Forbidden Planet was nomi- nated for an Oscar® (special effects) and is presented in CinemaScope with Color by DeLuxe. Print Courtesy of Warner Bros Distributing. Short Subjects: Jumpin’ Jupiter (1955) Warner Bros Merrie Melodies with Porky Pig Warner-Pathé Newsreel Highlights of 1956 Alex Film Society P O Box 4807 Glendale, CA 91222 www.AlexFilmSociety.org ©2007 AFS FORBIDDEN PLANEt Directed by ..................................Fred McLeod Wilcox Color – 1956 – 98 minutes CinemaScope Produced by ................................Nicholas Nayfack Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Story by ........................................Irving Block & Allen Adler Print Courtesy of Warner Bros Based on William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” Screenplay by .............................Cyril Hume CAST CREW Walter Pidgeon ......................................Dr. Edward Morbius Cinematographer ............................. George J. Folsey Anne Francis ..........................................Altaira Morbius Editor................................................... Ferris Webster Leslie Nielsen .........................................Commander John J. Adams Production Designers ..................... Irving Block* Warren Stevens .....................................Lt. ‘Doc’ Ostrow Mentor Huebner* Jack Kelly .................................................Lt. Jerry Farman Art Directors ...................................... Cedric Gibbons & Arthur Lonergan Richard -

Tempest-Study-Guide-Final.Pdf

THE PLAY Synopsis Prospero, magician and rightful Duke of Milan, has been stranded for 12 years on an island with his daughter Miranda as part of a plot by his brother, Antonio, to depose him. Having great magic power, Prospero is reluctantly served by the spirit Ariel (whom he saved from being trapped in a tree) and Caliban, son of the witch Sycorax. Prospero promises to release Ariel eventually to maintain his loyalty. Caliban is kept enslaved as punishment for attempting to attack Miranda. The play begins with Prospero using his powers to wreck a ship Antonio is traveling in with his counselors on the shores of the island. Prospero separates the survivors with his spells. Two drunkard clowns, Stephano and Trinculo, fall in with Caliban by convincing him that they came from the moon. They stage a failed rebellion against Prospero. Ferdinand, son of King Alonso of Naples (a conspirator who helped depose Prospero), is separated from the others and Prospero attempts to set up a romantic relationship between him and Miranda. Though the two young people fall immediately in love, Prospero enlists Ferdinand as a servant because he fears that "too light winning [may] make the prize light,” or that Ferdinand may not value Miranda enough without having to work for her. Antonio and Sebastian conspire to kill Alonso so that Sebastian may become King of Naples. Ariel interrupts their machinations by appearing as a Harpy, demanding that each of the conspiratorial nobles make amends for their overthrowing of Prospero's rightful dukedom. Prospero manipulates each group through his magic, drawing them to him. -

The Dark Side of Hollywood

TCM Presents: The Dark Side of Hollywood Side of The Dark Presents: TCM I New York I November 20, 2018 New York Bonhams 580 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 24838 Presents +1 212 644 9001 bonhams.com The Dark Side of Hollywood AUCTIONEERS SINCE 1793 New York | November 20, 2018 TCM Presents... The Dark Side of Hollywood Tuesday November 20, 2018 at 1pm New York BONHAMS Please note that bids must be ILLUSTRATIONS REGISTRATION 580 Madison Avenue submitted no later than 4pm on Front cover: lot 191 IMPORTANT NOTICE New York, New York 10022 the day prior to the auction. New Inside front cover: lot 191 Please note that all customers, bonhams.com bidders must also provide proof Table of Contents: lot 179 irrespective of any previous activity of identity and address when Session page 1: lot 102 with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW submitting bids. Session page 2: lot 131 complete the Bidder Registration Los Angeles Session page 3: lot 168 Form in advance of the sale. The Friday November 2, Please contact client services with Session page 4: lot 192 form can be found at the back of 10am to 5pm any bidding inquiries. Session page 5: lot 267 every catalogue and on our Saturday November 3, Session page 6: lot 263 website at www.bonhams.com and 12pm to 5pm Please see pages 152 to 155 Session page 7: lot 398 should be returned by email or Sunday November 4, for bidder information including Session page 8: lot 416 post to the specialist department 12pm to 5pm Conditions of Sale, after-sale Session page 9: lot 466 or to the bids department at collection and shipment. -

Introduction to Shakespeare Is an Introduction to Literature; It Is Also an Introduction to Shakespeare Studies and by Extension an Introduction to Literary Studies

INTRODUCTION TO Shakespeare Jeffrey R. Wilson (Undergrad Syllabus ) COURSE DESCRIPTION How does Shakespeare help us understand the world we live in? Why is he the most celebrated English author? How should his plays be performed today? What were his politics, and what are the politics of working with Shakespeare now? Because Shakespeare is such a canonical author, an introduction to Shakespeare is an introduction to literature; it is also an introduction to Shakespeare studies and by extension an introduction to literary studies. Alert to these larger concerns, this course introduces students to some Shakespearean texts and contexts. Emphasis is placed on Shakespeare’s choice of drama— thus the plays are treated as plays, and experienced in performance—and on close reading and interpretation. But interpretation will be done in light of the traditions in and against which Shakespeare wrote, most especially the conventions of the four traditional Shakespearean genres: comedy, tragedy, history, and romance. Our readings will include the texts and contexts of Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Richard III, 1 Henry VI, The Merchant of Venice, and The Tempest, as well as their modern afterlives. We’ll discuss Shakespeare’s reception—how a provincial playwright came to be England’s literary figurehead—and adaptations that span the globe, some of them speaking back to Shakespeare, with fire, in addition to some recent trends in Shakespeare studies, especially interdisciplinary work. REQUIRED TEXT The Norton Shakespeare. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt, third edition. Norton, 2015. COURSE SCHEDULE Weeks 1-2: Interpretation Hamlet (1602-03) Week 3: Text Hamlet, first quarto edition (1603) Hamlet, second quarto edition (1605) Hamlet, first folio edition (1623) Week 4: Collaboration Marlowe, Nashe, Shakespeare, and others, 1 Henry VI (rev. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

From Shakespeare to the Good Wife: Wendall & Wootton Hit Melbourne for Industry Talks Also Featuring David Field & Cezary Skubiszewski

FROM SHAKESPEARE TO THE GOOD WIFE: WENDALL & WOOTTON HIT MELBOURNE FOR INDUSTRY TALKS ALSO FEATURING DAVID FIELD & CEZARY SKUBISZEWSKI Do Laurence Olivier, The Good Wife, Shakespeare and Alien Invasions have anything in common? Punters attending the Wendall Thomas Talks Scripts and Adrian Wootton Talks Shakespeare series will find out! Organised by the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) Industry Programs Unit, which stages film financing event MIFF 37ºSouth Market and the Accelerator emerging director workshop, the Wendall Thomas Talks Scripts and Adrian Wootton Talks Shakespeare series are ticketed events open to the general public – be they film or media students, aspiring or existing screen practitioners, film aficionados or Just the plain curious. MIFF Accelerator Master-classes: Additionally, MIFF Accelerator presents several ticketed sessions, including an Acting Masterclass with David Field (Chopper, The Rover, and MIFF 2016’s Centrepiece Gala Down Under), Editing with Simon Njoo (editor of The Babadook and MIFF 2016’s Premiere Fund-supported Bad Girl), Production Design with Ben Morieson (Oddball and MIFF 2016’s MIFF Premiere Fund-supported Opening Night film The Death & Life of Otto Bloom), Cinematography with Andrew Commis (The Daughter, The Rocket and MIFF 2016’s Spear), and Composing with Cezary Skubiszewski (Sapphires, Red Dog and MIFF 2016’s Premiere Fund-supported Monsieur Mayonnaise). More details at http://miffindustry.com/ticketed-events16 Adrian Wootton Talks Shakespeare: Former British Film Institute and London Film Festival Director Adrian Wootton returns exclusively to Melbourne for another series of his acclaimed Illustrated Film Talks, focusing this year on the rich screen legacy of most filmed author ever - William Shakespeare, who died 400 years ago and whose works have inspired hundreds of screen productions.