Denver Landmark Preservation Commission Individual Structure Landmark Designation Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL NEWS IS a PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21St Century

LOCAL NEWS IS A PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21st Century INTRODUCTION A free and independent press was so fundamental to the founding vision of “Congress shall make no law democratic engagement and government accountability in the United States that it is called out in the First Amendment to the Constitution alongside individual respecting an establishment of freedoms of speech, religion, and assembly. Yet today, local newsrooms and religion, or prohibiting the free their ability to fulfill that lofty responsibility have never been more imperiled. At exercise thereof; or abridging the very moment when most Americans feel overwhelmed and polarized by a the freedom of speech, or of the barrage of national news, sensationalism, and social media, Colorado’s local news outlets – which are still overwhelmingly trusted and respected by local residents – press; or the right of the people are losing the battle for the public’s attention, time, and discretionary dollars.1 peaceably to assemble, and to What do Colorado communities lose when independent local newsrooms shutter, petition the Government for a cut staff, merge, or sell to national chains or investors? Why should concerned redress of grievances.” citizens and residents, as well as state and local officials, care about what’s happening in Colorado’s local journalism industry? What new models might First Amendment, U.S. Constitution transform and sustain the most vital functions of a free and independent Fourth Estate: to inform, equip, and engage communities in making democratic decisions? 1 81% of Denver-area adults say the local news media do very well to fairly well at keeping them informed of the important news stories of the day, 74% say local media report the news accurately, and 65% say local media cover stories thoroughly and provide news they use daily. -

![LOCAL AREA 3: METRO [Includes Counties of Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Clear Creek, Denver, Douglas, Elbert, Gilpin, Jefferson, Park]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1275/local-area-3-metro-includes-counties-of-adams-arapahoe-boulder-clear-creek-denver-douglas-elbert-gilpin-jefferson-park-11275.webp)

LOCAL AREA 3: METRO [Includes Counties of Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Clear Creek, Denver, Douglas, Elbert, Gilpin, Jefferson, Park]

LOCAL AREA 3: METRO [Includes Counties of Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Clear Creek, Denver, Douglas, Elbert, Gilpin, Jefferson, Park] Call Sign FIPS City of Freq Facilities EAS Monitoring Assignments Code License (CH) (N)ight (D)ay Title K16CM 08031 AURORA CH 16 39.2 KW Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 K17CF 08013 BOULDER CH 17 2.69 KW Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 K36CP 08031 AURORA CH 36 75.6 KW Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 K38DF 08031 AURORA CH 38 10.6 KW Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 K43DK 08031 DENVER CH 43 30.3 KW Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 K54DK 08013 BOULDER CH 54 1.18 KW Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 K57BT 08031 DENVER CH 57 4.9 KW Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 KALC 08031 DENVER 105.9 100. KW 448 Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 KBCO 08013 BOULDER 1190 0.11/5. KW ND-1 U PN LP-1, LP-2 NWS KBCO-FM 08013 BOULDER 97.3 100. KW 470 Meters PN LP-1, LP-2 NWS KBDI-TV 08013 BROOMFIELD CH 12 229 KW 738 Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 KBNO 08031 DENVER 1220 0.012/0.66 KW ND-1 U PN LP-1 LP-2 KBPI 08031 DENVER 106.7 100. KW 301 Meters PN LP-1, LP-2 NWS KBVI 08013 BOULDER 1490 1. KW ND-1 U PN, BSPP LP-1 LP-2 KCDC 08013 LONGMONT 90.7 .100 KW 82 Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 KCEC 08031 DENVER CH 50 2510 KW 233 Meters PN LP-1 LP-2 KCFR 08031 DENVER 90.1 50. -

Detailed Table of Contents (PDF Download)

CONTENTS Preface xix Introduction xxi Acknowledgments xxvii PART I CONTENT REGULATION 1 CHAPTER 1 BOOKS AND MAGAZINES 3 A. Violence 3 Rice v. Paladin Enterprises 4 Braun v. Soldier of Fortune Magazine, Inc. 11 Einmann v. Soldier of Fortune Magazine, Inc. 18 B. Censorship 25 Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan 25 CHAPTER 2 MUSIC 29 A. Violence 29 Weirum v. RKO General, Inc. 29 McCollum v. CBS, Inc. 33 Matarazzo v. Aerosmith Productions, Inc. 40 Davidson v. Time Warner 42 Pahler v. Slayer 51 B. Censorship 56 Luke Records v. Navarro 57 Marilyn Manson v. N.J. Sports & Exposition Auth. 60 Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad 71 xi xii Contents CHAPTER 3 TELEVISION 79 A. Violence 79 Olivia N. v. NBC 80 Graves v. WB 84 Zamora v. CBS 89 B. Censorship 94 Writers Guild of Am., West Inc. v. ABC, Inc. 94 F.C.C. v. Fox Television Stations, Inc. 103 CHAPTER 4 FILM 115 A. Violence 115 Byers v. Edmondson 117 Lewis v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. 122 B. Censorship 128 Swope v. Lubbers 128 Appendix 1: The Movie Rating System 134 United Artists Corporation v. Maryland State Board of Censors 141 Miramax Films Corp. v. Motion Picture Ass’n of Am., Inc. 145 C. Both Sides of the Censor Debate 151 MPAA Ratings Chief Defends Movie Ratings 151 Censuring the Movie Censors 153 CHAPTER 5 VIDEO GAMES 159 A. Violence 159 Watters v. TSR 160 James v. Meow Media 164 Sanders v. Acclaim Entertainment, Inc. 174 Wilson v. Midway Games 186 B. Censorship 189 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Assoc. -

2005 Annual Report

RESULTS Matter 2005 Annual Report The E.W. Scripps Company Mission The E.W.The Company Scripps 2005 Annual Report The E.W. Scripps Company strives for excellence in the products and services we produce and responsible service to the communities in which we operate. Our purpose is to continue to engage in successful, growing enterprises in the fields of information and entertainment. The company intends to expand, develop and acquire new products and services, and to pursue new market opportunities. Our focus shall be long-term growth for the benefit of shareholders and employees. P.O. Box 5380 Cincinnati, Ohio 45201 www.scripps.com The E. W. Scripps Company 2005 Annual Report Board of Directors RESULTS do matter and they’re what The E.W. Scripps 123456 Company is all about. Millions of engaged media consumers, and the advertisers and merchants who want to reach them, turn to 7 8 9 10 11 12 Scripps every day for a growing range of innovative information services that excel at delivering outstanding results. 1 William R. Burleigh, 70 3 Paul K. Scripps, 60 6 David A. Galloway, 62 8 Ronald W. Tysoe, 52 11 Jarl Mohn, 54 Chairman of the company since May 1999 and Chairman Retired Vice President/ Corporate Director; Vice Chairman, Trustee, Mohn of the Executive Committee since October 2000. He joined Newspapers, The E.W. retired President and Federated Department Family Trust; retired the Board of Directors in 1990. He served as President and Scripps Company. CEO, Torstar Corp. Stores Inc. Director President & Chief Chief Executive Officer from May 1996 until September 2000 Director since 1986. -

KLZ Radio, Inc. Annual EEO Report December 1, 2015 – November 30, 2016

KLZ Radio, Inc. Annual EEO Report December 1, 2015 – November 30, 2016 The purpose of this EEO Public File Report (Annual EEO report) is to comply with Section 73.2080(c)(6) of the FCC’s 2002 EEO Rule. This Report has been prepared on behalf of the Station Employment Unit that is comprised of the following station(s): Station City of License KLZ AM Denver, CO KLTT AM Commerce City, CO KLDC AM Denver, CO KLVZ AM Brighton, CO Section I. List all Full-Time Job Vacancies Filled by Each Station in the Employment Unit: Full-time Date Total # Recruitment Sources Recruitment Positions Filled by Position Interviewed Utilized Source of Hire Job Title Hired Producer/Board 4/1/16 7 4a,7,10,19,20,23,37,38,39,42,44,49 42 Op KLZ 5/31/16 6 4a,5,9a,12,15,23,37,39 4a Writer/Producer KLZ 6/7/16 10 4a,5,9a,12,15,23,38,39,42 9a Writer/Producer KLTT Admin 7/18/16 10 6,7,9,9a,10,11,23,39,41,42,44 42 Assist. Board 10/20/16 6 5,7,9a,10,12,21,23,29,37,38,40,41,42,55 42 Op/Producer Sales 10/31/16 6 5,9,9a,12,23,37,39,41,48,51, 9a Person/Account Exec. Total # of Interviewees Referred by Each Source: For the period from December 1, 2015 to November 30, 2016 this Employment Unit interviewees –45 Full time job vacancies--6 Stations KLZ/KLTT/KLDC/KLVZ are Equal Opportunity Employers Section II. -

KCFR, KVOD – Denver, CO KCFC - Boulder, CO

PUBLIC BROADCASTING OF COLORADO, INC. RECRUITING/OUTREACH ACTIVITIES KCFR, KVOD – Denver, CO KCFC - Boulder, CO Participation in job fair: Colorado State University Career Fair September 15, 2004 Participation in job fair: University of Colorado School of Journalism and Mass Communication Career Group October 27, 2004 Participation in job fair: Denver Post Career Fair November 9, 2004 A Leadership Development Training program for managers was started during the past year to develop leadership skills among the senior management team. General management training that includes assuring equal employment opportunities and preventing discrimination also is an ongoing process, particularly with new managers. Public Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. (“PBC”) is a member of the National Association of Broadcasters and the Colorado Broadcasters Association, which both have Internet websites that discuss careers and career opportunities in the broadcasting industry. When PBC receives inquiries from people interested in broadcasting employment opportunities, in addition to responding to their inquiries, PBC may direct them to these websites to help provide additional information that may be responsive to their questions. In addition to the above, all positions are posted on the Colorado Public Radio website which currently gets about 30,000 hits/month, as well as the National Public Radio website which gets millions of hits/month. PBC is in the process of designing an internship program that it expects will become fully functional in early 2005. The internship program will assist members of the community to acquire skills needed for employment at a broadcast station. PBC expects to provide internships in its programming, development, engineering and administration departments. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

Gerald R. Ford Administration White House Press Releases

Digitized from Box 8 of the White House Press Releases at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Office of the White House Press Secretary ----------------------------------------------------------------------- NOTICE TO THE PRESS INVITEES TO THE RECEPTION FOR BROADCAST EXECUTIVES THE BLUE ROOM Wednesday, March 12, 1975 Mr. John Murphy, President Avco Broadcasting Corporation Cincinnati, Ohio Mr. Arch L. Madsen, President Bonn~ville International Corporation Salt Lake City, Utah Mr. Thomas S. Murphy Board Chairman Capital Cities Communications, Inc. New York, New York Mr. C. Wrede Petersmeyer Chairman and President Corinthian Stations New York, New York Mr. Clifford M. Kirtland, Jr., President Cox Broadcasting Corporation Atlanta, Georgia Mr. Rei4 L. Shaw, President General Electric Broadcasting Company Schenectady, New York Mr. John T. Reynolds. President, Television Division Golden West Broadcaster Stations Los Angeles, California Mr•. Franklin C. Snyder Vice President, Broadcast Division Hearst Corporation Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (MORE) - 2 - Mr. Norman. E. Walt, President McGraw-Hill Broadcasting Company New York, New York Mr. Clem Weber Executive Vice President New York, New York Mr. E. R. Vadeboncoeur, President Newhouse Broadcasting Stations Syracuse, New York Mr. August C. Meyer, Sr. President Mr. August C. Meyer, Jr. Secretary-Treasurer Midwest Television, Inc. Champaign, Illinois Mr. T. Ballard Morton, President Orion Broadcasting Stations Louisville, Kentucky Mr. Joel Chaseman, President Pos t-Newsweek Stations Washington, D. C. Mr. Frank Shakespeare, President RKO General, Inc. New York, New York Mr. Marshall Berkman, President Rust Craft Broadcasting Company Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Mr. Peter B. Storer, President Storer Broadcasting Company Miami Beach, Florida Mr. Charles S. Mecham, Jr. Board Chairman Taft Broadcasting Cincinnati, Ohio (MORE) - 3 - Mr. -

Workbook 7.Indd

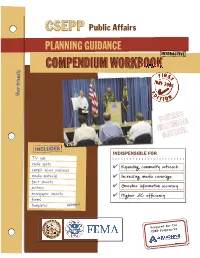

CSEPPCSEPP Public Affairs PLANNING GUIDANCE COMPENDIUM WORKBOOK CONTAINS MULTIMEDIA MATERIAL INCLUDES INDISPENSIBLE FOR TV ads radio spots Expanding community outreach sample news releases media material Increasing media coverage fact sheets posters Greater information accuracy newspaper inserts Higher JIC efficiency forms re! templates and mo for the Prepared ram by CSEP Prog 2 ☞ Instructions Th is Workbook CD contains the following elements. Th ere are no hyperlinks between them. Main document PDF fi le (what you are reading now). Th ere are also three kinds of supporting documents on the CD. Th ey are listed in the text with their titles in blue italics. On the CD, they are organized within folders that are named and numbered to correspond to the sections of this main document. Supporting documents in PDF format. Th ey can be opened with Acrobat Reader (a free download from www.adobe.com). If you are reading this, Reader is already installed on your computer. Th ese documents are QuickTime multimedia fi les — audio for the radio spots and audio+video for the television spots. You must have QuickTime installed on your computer to see and/or hear these fi les. QuickTime is a free download from www.apple.com. Make sure your speakers are connected and your computer’s sound is turned on. Microsoft Word fi les. Th ey can be opened in Word and used as modifi able templates. PowerPoint presentation. Graphics fi les are provided in these formats, in addition to PDF. Th ese can be imported into art editing and page layout programs. Th e icons indicate, left to right, Adobe Illustrator, Encapsulated PostScript, Joint Experts Photographic Group (also known as JPEG, a standard format for use on the Web), and Tagged Image Format. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 6.0 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT .................................................................................. 6-1 6.1 Objectives...........................................................................................................6-1 6.2 Elements of Program..........................................................................................6-1 6.3 Agency Input ......................................................................................................6-6 6.4 Public Input.......................................................................................................6-11 6.5 Special Outreach to Low-Income and Minority Populations.............................6-20 6.6 Release of Draft EIS.........................................................................................6-25 6.7 Coordination Subsequent to Release of Final EIS ...........................................6-26 TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 6-1 Mailing Distribution Area.....................................................................................6-3 LIST OF TABLES Page Table 6-1 Local Media Contact List ....................................................................................6-5 Table 6-2 Agency and Local Government Involvement Activities.......................................6-7 Table 6-3 Summary of Citizen Working Group Meetings .................................................6-13 Table 6-4 Local Neighborhood Associations and Business Groups.................................6-15 Table 6-5 -

L-:I, by Local Townspeople? None (}

1. What is the most widely-read city daily newspaper in your area (e.g. Denver Post, Billings Gazette, Scottsbluff Star-Herald, etc.)? Denver Post - Rocky Mountain News - Greeley Tribune 2. What is the most widely-read local newspaper in your area (e.g. The Platteville Herald, the Lovell Chronicle, the Bayard Transcript, etc.)? Eaton Herald - Highland Today 3. What is the most widely-read agriculturally-oriented magazine in your area? Colorado Rancher & Farmer- Farm Journal - Upbeet - Sugar Beet Grower 4. Which city radio station is most listened to by growers in your area (e.g. KOA Denver)? KOA * KLZ • KHOW Denver By local townspeople? KOA * KLZ • KHOW Denver 5. Which local radio station is most listened to by growers in your area? . KFKA - KYOU - Greeley KUAD Windsor By local townspeople? KFKA - KYOU -Greeley KUAD Windsor 6. Which city television·station is watched most by growers in your area? Channel 2 - 4 - 7 - 9 Denver By local townspeople? Channel 2 - 4 - 7 - 9 Denver 7. Which local television station is watched most by growers in your area? None 1.,, - ':l-:i, By local townspeople? None (}. _ '-\ ...1 ,.q 8. Which radio-TV farm broadcaster is most popular in your area? Evan Slack Ed ~ollins 9. What is the favorite gathering place in your area? P~erce Cafe, Eaton Country Club Eaton Pool Hall, Franz Cafe, Prducer's Sale Greeley, McClures John Deere 10. What are major activities in which people in your area are interested? Agriculture, Local Sports, Schools, Church "°' o a e e ive most res ected o 1 10n or oug t eaders in your co mu 1 y (should not necessarily be restricted to growers)? A._____ M_r _. -

A TIMELINE for GOLDEN, COLORADO (Revised October 2003)

A TIMELINE FOR GOLDEN, COLORADO (Revised October 2003) "When a society or a civilization perishes, one condition can always be found. They forgot where they came from." Carl Sandburg This time-line was originally created by the Golden Historic Preservation Board for the 1995 Golden community meetings concerning growth. It is intended to illustrate some of the events and thoughts that helped shape Golden. Major historical events and common day-to-day happenings that influenced the lives of the people of Golden are included. Corrections, additions, and suggestions are welcome and may be relayed to either the Historic Preservation Board or the Planning Department at 384-8097. The information concerning events in Golden was gathered from a variety of sources. Among those used were: • The Colorado Transcript • The Golden Transcript • The Rocky Mountain News • The Denver Post State of Colorado Web pages, in particular the Colorado State Archives The League of Women Voters annual reports Golden, The 19th Century: A Colorado Chronicle. Lorraine Wagenbach and Jo Ann Thistlewood. Harbinger House, Littleton, 1987 The Shining Mountains. Georgina Brown. B & B Printers, Gunnison. 1976 The 1989 Survey of Historic Buildings in Downtown Golden. R. Laurie Simmons and Christine Whitacre, Front Range Research Associates, Inc. Report on file at the City of Golden Planning and Development Department. Survey of Golden Historic Buildings. by R. Laurie Simmons and Christine Whitacre, Front Range Research Associates, Inc. Report on file at the City of Golden Planning and Development Department. Golden Survey of Historic Buildings, 1991. R. Laurie Simmons and Thomas H. Simmons. Front Range Research Associates, Inc.