“Wrong, Or at Best Misleading”: Public Policy and the Slow Recovery in Australia, 1990 – 1994 Joshua Black, the Australian National University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

Attachment a (Sub 43A) the TOOMER AFFAIR' AUTHORITY's CRIMINAL CULTURE of RETRIBUTION & COVER UP

Attachment A (Sub 43a) THE TOOMER AFFAIR' AUTHORITY'S CRIMINAL CULTURE OF RETRIBUTION & COVER UP By Keith Potter - 32 years diverse employment with the Australian Public Service, plus 28 years involvement in whistleblowing matters. Foreword: Authority's criminal culture of retribution and cover up has seriously damaged numerous whistleblowers and dissenters, and further harmed the public interest. This is exemplified by the case of Bill Toomer and his family, and irreparable damage to quarantine protection of public health and rural resources. Authority's culture of retribution seriously damaged Mr Toomer and his family. Occasional glimpses of their life are accordingly included. I have his permission to include this information. Summary: Bill Toomer was the Senior Quarantine and Grain Ships Inspector for Western Australia when he was demoted on disciplinary grounds for making false and unauthorised statement to the media. According to official reports he was an overzealous, egotistical and disobedient officer of such difficult character that he had to be transferred to Victoria "in the public interest" because he was unemployable in WA. The reality is that his problems started in Victoria where his thoroughness of inspection, and refusal of bribes, resulted in unscheduled ship fumigations. The resultant delays incurred considerable costs to the ship owners, mostly influential overseas owners, and problems for their Australian agents. His wings were clipped before he was returned to Victoria for final despatch. An officer of one of the Victorian sub agents to James Patrick Stevedoring P/L testified under oath that he was told that Toomer would be sent to WA where he would be "fixed up". -

Audit Report No. 46, 1999–2000

'LVVHQWLQJ5HSRUW Audit Report No. 46, 1999–2000 High Wealth Individuals Taskforce Australian Taxation Office This dissenting report deals with the failure of the Government to legislate to deal with large scale tax avoidance and evasion techniques utilising trusts. Introduction The High Wealth Individuals Taskforce was established by the Commissioner of Taxation in May 1996 as an administrative response to a major problem the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) had identified late in the previous year. Advice to the Previous Government Trusts can provide a vehicle for a number of tax avoidance and evasion techniques. Throughout 1994 and 1995 the Treasurer’s office pressed Treasury for advice on the extent of the problem and possible remedies. It was raised almost weekly but nothing was forthcoming until November 9, 1995 when the ATO advised that it had uncovered a significant problem using multiple trust structures. The ATO had obtained software which was capable of finding patterns in large amounts of seemingly unrelated information. Using it, they had found that large numbers of seemingly unrelated trusts were related and a range of techniques were being used by high wealth individuals to reduce tax liabilities to low or negligible levels. Treasury and the ATO worked on the issue over the next three months, eventually advising the Treasurer that it would be appropriate to make a 74 public announcement that the government would act to end these practices. The press release issued by then Treasurer Ralph Willis on 11 February 1996 was written directly from the Treasury and ATO advice. It was titled, High Wealth Individuals - Taxation of Trusts, and in full, it read: On November 9, 1995 I was informed by the Australian Taxation Office that as part of the Compliance Enforcement Strategy, authorised by the Government, it had conducted analysis of the accumulation of wealth by certain individuals and the taxes paid by them. -

Legislation and Regulations, Media Releases and Policy Statements and Publications

Appendix B Legislation and regulations, media releases and policy statements and publications Legislation and regulations, media releases and policy statements and publications Legislation and regulations Current 1. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Act No. 92 of 1975 as amended: see Appendix D) 2. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Regulations 1989 (Statutory Rules No. 177 of 1989 as amended: see Appendix E) 3. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers (Notices) Regulations (Statutory Rules No. 226 of 1975 as amended: see Appendix E) Historical 1. Companies (Foreign Take-overs) Act 1973, No. 199 of 1973 — December 1973. 2. Companies (Foreign Take-overs) Act 1972, No. 134 of 1972 — November 1972. 83 Foreign Investment Review Board Annual Report 2005-06 Media releases and policy statements 1. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Qantas Offer — 14 December 2006. 2. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Foreign Investment: Brambles Industries Limited — 9 November 2006. 3. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Foreign Investment Proposal: Thales Australia Holdings Pty Limited — Acquisition of remaining 50 per cent interest in ADI Limited — 12 October 2006. 4. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Reappointment of member of Foreign Investment Review Board [Ms Lynn Wood] — 29 April 2005. 5. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — BHP Billiton Group — No objections raised to the acquisition of WMC Resources Limited, subject to conditions — 4 April 2005. 6. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Xstrata Plc — No objections raised to the acquisition of WMC Resources Limited, subject to conditions — 11 February 2005. -

Briefings: ACTU/ALP Accord

BRIEFINGS / • MMMM • Cockatoo Dockyard construction. ACTU/ALP Accord A u s t r a l i a n L e f t R e v ie w 86 After almost a year of about to be set up — but it that the Australian operation, the prices and is a "toothless tiger" in Clif dockyards should get the incomes accord reached Dolan's words. Petrol, contracts. But the govern between the Labor Party postal and phone charges ment, heavily invluenced and the ACTU before the are the only areas to come by the bureaucracy, has election is in danger of within the authority's stuck to past traditions of becoming superfluous to jurisdiction! Control of using the main criteria as the Hawke government's non-wage incomes, like competitiveness with operations. The document doctors' fees, and share overseas dockyards, with negotiated over many dividends, has been job creation and industry months between Labor ignored. development relegated as spokespeople Ralph Willis The accord says: "On priorities. and Bill Hayden was taken taking office the govern The W illiamstown over by Bob Hawke and ment will substantially dockyard, of course, did Paul Keating and con restructure the income tax get contracts for the sequently underwent some scale to ease the tax construction of frigates for transformation of purpose. burden on low and middle the Navy — but only Although Willis, as income earners". The reluctantly, with dire Industrial Relations government has made warnings being given by Minister, retains some vague references about a the Defence Minister about involvement in the work review of the tax scales the need for fewer disputes ings of the accord, the main next year, which might lead if the contracts were to be control over its implement to some reform two years kept. -

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Robert J. Bookmiller Gulf Research Center i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Dubai, United Arab Emirates (_}A' !_g B/9lu( s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ *_D |w@_> TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B uG_GAE#'c`}A' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGLi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' , ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published 2009 i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in |w@_> a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. -

Murray Goot- Public Opinion and the Democratic Deficit

Public Opinion and the Democratic Deficit: Australia and the War Against Iraq by Murray Goot © all rights reserved. To facilitate downloading, this paper has been divided into parts I & II A few weeks after the return of the Howard Government, in November 2001, I was invited to speak at a joint meeting in Canberra of the Academy of Humanities in Australia and the Academy of the Social Sciences. At that time, the Prime Minister’s reputation as a man who fashioned his policies on the basis of opinion polls was at its height; not long before no less a figure than Paul Kelly, the country’s most distinguished political journalist, had described John Howard as ‘the most knee-jerk, poll-reactive, populist prime minister in the past 50 years’ (2000). Many in the audience were convinced that this was precisely how Howard had fashioned his government’s policies on a whole raft of issues, not least those to do with ‘race’; that it was on the basis of such policies, especially in relation to refugees, that his government had been returned; and for doing it they considered him deserving of the deepest disapprobation. Shortly before the Howard Government announced, on February 18, that Australia would join the United States and Britain in their attempt to disarm Iraq, I was invited to Canberra by another group of academics concerned that Howard was about to embroil Australia in a conflict without the formal authorisation of the Parliament; that far from following public opinion on the issue he was prepared to defy it; and that even for contemplating such a course they considered him deserving of the deepest disapprobation. -

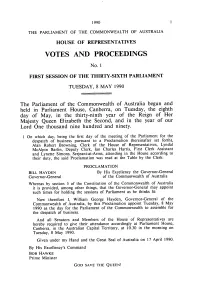

Votes and Proceedings

1990 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 8 MAY 1990 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the eighth day of May, in the thirty-ninth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and ninety. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Alan Robert Browning, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Deputy Clerk, Ian Charles Harris, First Clerk Assistant and Lynette Simons, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION BILL HAYDEN By His Excellency the Governor-General Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Whereas by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is provided, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, William George Hayden, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Tuesday, 8 May 1990 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business. And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 10.30 in the morning on Tuesday, 8 May 1990. -

Australia: Background and U.S

Order Code RL33010 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Australia: Background and U.S. Relations Updated April 20, 2006 Bruce Vaughn Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Australia: Background and U.S. Interests Summary The Commonwealth of Australia and the United States are close allies under the ANZUS treaty. Australia evoked the treaty to offer assistance to the United States after the attacks of September 11, 2001, in which 22 Australians were among the dead. Australia was one of the first countries to commit troops to U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. In October 2002, a terrorist attack on Western tourists in Bali, Indonesia, killed more than 200, including 88 Australians and seven Americans. A second terrorist bombing, which killed 23, including four Australians, was carried out in Bali in October 2005. The Australian Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, was also bombed by members of Jemaah Islamiya (JI) in September 2004. The Howard Government’s strong commitment to the United States in Afghanistan and Iraq and the recently negotiated bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Australia and the United States have strengthened what were already close ties between the two long-term allies. Despite the strong strategic ties between the United States and Australia, there have been some signs that the growing economic importance of China to Australia may influence Australia’s external posture on issues such as Taiwan. Australia plays a key role in promoting regional stability in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific. -

Black Holes to Surplus Budgets

Howard Government Retrospective II, University of NSW, Canberra 15 November 2017 “To the Brink 1997-2001” Black Holes to Surplus Budgets Speech by Hon Peter Costello AC P a g e 1 | 11 Black Holes to Surplus Budgets The last Budget of the Keating Government was delivered by Ralph Willis on 9 May 1995. “The Budget delivers a surplus in 1995-96 of $718 million”, he said and went on: “Importantly, the Budget for 1996-97 will be in surplus excluding asset sales and special debt and capital repayments. And the budget surplus by 1998-99 will be $7.4 billion or 1.2 percent of GDP” Chart 1 of Budget Paper No. 1 (see Annexure A) showed a Budget with surpluses right across the forward estimates. Now one had to be careful with these sorts of claims. In those days, the Government reported what we now call a “Headline Balance”. If the Government sold an asset, the full amount of the proceeds were included on the bottom-line. Believe it or not it was treated as a “negative outlay”, effectively a cut in expenditure. So, in the 1995-96 Budget when Willis announced the sale of the Commonwealth’s remaining 50.4% equity in the Commonwealth Bank in two instalments, one to be received in 1995-96 and the other in 1997-98, the Budget bottom line was boosted by these one-off receipts from privatisation. ¹ Of the year in between, 1996-97- the first Budget for an incoming Government- Willis went out of his way to say it would be in surplus “excluding asset sales and special debt and capital repayments”. -

Companion (Ac) in the General Division of the Order of Australia

COMPANION (AC) IN THE GENERAL DIVISION OF THE ORDER OF AUSTRALIA Dr Martin Lee PARKINSON PSM, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 1 National Circuit, Barton ACT 2601 For eminent service to the Australian community through leadership in public sector roles, to innovative government administration and high level program delivery, to the development of economic policy, and to climate change strategy. Service includes: Secretary, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, since 2016. Secretary, Department of the Treasury, 2011-2014. Secretary, Department of Climate Change, Energy Efficiency and Water, 2010-2011. Secretary, Department of Climate Change, 2007-2010. Deputy Secretary, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2007. Deputy Secretary, Department of the Treasury, 2001-2007. Chair, Prime Minister's Task Group on Energy Efficiency, 2010. Head, Prime Minister's Task Group on Emissions Trading, 2006-2007. Senior Advisor to Federal Treasurers John Kerin, 1991, Ralph Willis, 1991, John Dawkins, 1991-1993. Involved in: The development of the Capital Gains Tax. Policy Development and Review Department, International Monetary Fund (IMF), 1997-2001. Australian G20 Deputy Finance Minister, Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Meeting, Melbourne, 2006. Non-Executive Director, ORICA Limited, 2015. Non-Executive Director, O'Connell Street Associates, 2015. Non-Executive Director, German-Australian Chamber of Industry and Commerce, 2015. Member, Policy Committee, Grattan Institute, 2015. Member, Advisory Board, Future Directions Project, Australian Federal Police, 2015-2016. Board Member, Reserve Bank of Australia, 2011-2014. Chair, Advisory Board, Australian Office of Financial Management, 2011-2014. Ex-officio Member, Board of Taxation, 2011-2014. Chair, Standard Business Reporting Board, 2011-2014. -

Hawke: the Prime Minister

book reviews the Left, especially Ian Buruma Hawke: The Prime Minister from the float strengthened, but and Timothy Garton Ash, treat By Blanche d’Alpuget for d’Alpuget only Hawke can Ramadan highly positively, yet Melbourne University Press, take credit. denigrate more liberal Muslim 2010 d’Alpuget barely covers the figures—especially the Somali-born $44.95, 401 pages deregulation of the banking sector Dutch citizen Ayaan Hirsi Ali. ISBN 9780522856705 or Keating’s role in putting together Berman’s outrage and anger begins the detail of the policy together, to burn through as he demonstrates awke: The Prime Minister underplaying his contribution to their subtle condescension, their Hhas been written to confirm the government from the start. arguable sexism, their dismissal the ‘great man’ view of history, Hawke’s great contribution as a of her ideas, and their absurd which is not surprising given Labor leader, aside from winning efforts to paint Hirsi Ali as an Blanche d’Alpuget is Bob Hawke’s four elections, was the Accord. In ‘enlightenment fundamentalist.’ current wife. The result this landmark change In the end, this final burst of is that Hawke’s judgment for labour relations in white heat is illuminating. is depicted as near Australia, the major Berman demonstrates that what peerless and he is seen as unions and the Hawke Western intellectuals are doing having full ownership of government agreed to is in fact adopting the categories the reform legacy of his arbitrated wage increases of the Islamist movement governments. It would that were lower than rises themselves—to whom Qaradawi have been a better book if in inflation in exchange is an orthodox moderate and it were less cavalier in its for social benefits such Ramadan is half-way lost to portrayal of Hawke and as universal health care, Western liberalism while Hirsi Ali more willing to credit superannuation, and tax is ‘an infidel fundamentalist,’ as she his team of ministers for reforms benefiting low- was labelled by the murderer of her successes.