Black Holes to Surplus Budgets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategy-To-Win-An-Election-Lessons

WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 i The Institute of International Studies (IIS), Department of International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada, is a research institution focused on the study on phenomenon in international relations, whether on theoretical or practical level. The study is based on the researches oriented to problem solving, with innovative and collaborative organization, by involving researcher resources with reliable capacity and tight society social network. As its commitments toward just, peace and civility values through actions, reflections and emancipations. In order to design a more specific and on target activity, The Institute developed four core research clusters on Globalization and Cities Development, Peace Building and Radical Violence, Humanitarian Action and Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. This institute also encourages a holistic study which is based on contempo- rary internationalSTRATEGY relations study scope TO and WIN approach. AN ELECTION: ii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 By Dafri Agussalim INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITAS GADJAH MADA iii WINNING ELECTIONS: LESSONS FROM THE AUSTRALIAN LABOR PARTY 1983-1996 Penulis: Dafri Agussalim Copyright© 2011, Dafri Agussalim Cover diolah dari: www.biogenidec.com dan http:www.foto.detik.com Diterbitkan oleh Institute of International Studies Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Gadjah Mada Cetakan I: 2011 x + 244 hlm; 14 cm x 21 cm ISBN: 978-602-99702-7-2 Fisipol UGM Gedung Bulaksumur Sayap Utara Lt. 1 Jl. Sosio-Justisia, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta 55281 Telp: 0274 563362 ext 115 Fax.0274 563362 ext.116 Website: http://www.iis-ugm.org E-mail: [email protected] iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book is a revised version of my Master of Arts (MA) thesis, which was written between 1994-1995 in the Australian National University, Canberra Australia. -

Audit Report No. 46, 1999–2000

'LVVHQWLQJ5HSRUW Audit Report No. 46, 1999–2000 High Wealth Individuals Taskforce Australian Taxation Office This dissenting report deals with the failure of the Government to legislate to deal with large scale tax avoidance and evasion techniques utilising trusts. Introduction The High Wealth Individuals Taskforce was established by the Commissioner of Taxation in May 1996 as an administrative response to a major problem the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) had identified late in the previous year. Advice to the Previous Government Trusts can provide a vehicle for a number of tax avoidance and evasion techniques. Throughout 1994 and 1995 the Treasurer’s office pressed Treasury for advice on the extent of the problem and possible remedies. It was raised almost weekly but nothing was forthcoming until November 9, 1995 when the ATO advised that it had uncovered a significant problem using multiple trust structures. The ATO had obtained software which was capable of finding patterns in large amounts of seemingly unrelated information. Using it, they had found that large numbers of seemingly unrelated trusts were related and a range of techniques were being used by high wealth individuals to reduce tax liabilities to low or negligible levels. Treasury and the ATO worked on the issue over the next three months, eventually advising the Treasurer that it would be appropriate to make a 74 public announcement that the government would act to end these practices. The press release issued by then Treasurer Ralph Willis on 11 February 1996 was written directly from the Treasury and ATO advice. It was titled, High Wealth Individuals - Taxation of Trusts, and in full, it read: On November 9, 1995 I was informed by the Australian Taxation Office that as part of the Compliance Enforcement Strategy, authorised by the Government, it had conducted analysis of the accumulation of wealth by certain individuals and the taxes paid by them. -

Legislation and Regulations, Media Releases and Policy Statements and Publications

Appendix B Legislation and regulations, media releases and policy statements and publications Legislation and regulations, media releases and policy statements and publications Legislation and regulations Current 1. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Act No. 92 of 1975 as amended: see Appendix D) 2. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Regulations 1989 (Statutory Rules No. 177 of 1989 as amended: see Appendix E) 3. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers (Notices) Regulations (Statutory Rules No. 226 of 1975 as amended: see Appendix E) Historical 1. Companies (Foreign Take-overs) Act 1973, No. 199 of 1973 — December 1973. 2. Companies (Foreign Take-overs) Act 1972, No. 134 of 1972 — November 1972. 83 Foreign Investment Review Board Annual Report 2005-06 Media releases and policy statements 1. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Qantas Offer — 14 December 2006. 2. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Foreign Investment: Brambles Industries Limited — 9 November 2006. 3. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Foreign Investment Proposal: Thales Australia Holdings Pty Limited — Acquisition of remaining 50 per cent interest in ADI Limited — 12 October 2006. 4. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Reappointment of member of Foreign Investment Review Board [Ms Lynn Wood] — 29 April 2005. 5. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — BHP Billiton Group — No objections raised to the acquisition of WMC Resources Limited, subject to conditions — 4 April 2005. 6. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Xstrata Plc — No objections raised to the acquisition of WMC Resources Limited, subject to conditions — 11 February 2005. -

Briefings: ACTU/ALP Accord

BRIEFINGS / • MMMM • Cockatoo Dockyard construction. ACTU/ALP Accord A u s t r a l i a n L e f t R e v ie w 86 After almost a year of about to be set up — but it that the Australian operation, the prices and is a "toothless tiger" in Clif dockyards should get the incomes accord reached Dolan's words. Petrol, contracts. But the govern between the Labor Party postal and phone charges ment, heavily invluenced and the ACTU before the are the only areas to come by the bureaucracy, has election is in danger of within the authority's stuck to past traditions of becoming superfluous to jurisdiction! Control of using the main criteria as the Hawke government's non-wage incomes, like competitiveness with operations. The document doctors' fees, and share overseas dockyards, with negotiated over many dividends, has been job creation and industry months between Labor ignored. development relegated as spokespeople Ralph Willis The accord says: "On priorities. and Bill Hayden was taken taking office the govern The W illiamstown over by Bob Hawke and ment will substantially dockyard, of course, did Paul Keating and con restructure the income tax get contracts for the sequently underwent some scale to ease the tax construction of frigates for transformation of purpose. burden on low and middle the Navy — but only Although Willis, as income earners". The reluctantly, with dire Industrial Relations government has made warnings being given by Minister, retains some vague references about a the Defence Minister about involvement in the work review of the tax scales the need for fewer disputes ings of the accord, the main next year, which might lead if the contracts were to be control over its implement to some reform two years kept. -

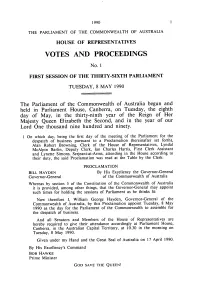

Votes and Proceedings

1990 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 8 MAY 1990 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the eighth day of May, in the thirty-ninth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and ninety. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Alan Robert Browning, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Deputy Clerk, Ian Charles Harris, First Clerk Assistant and Lynette Simons, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION BILL HAYDEN By His Excellency the Governor-General Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Whereas by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is provided, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, William George Hayden, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Tuesday, 8 May 1990 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business. And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 10.30 in the morning on Tuesday, 8 May 1990. -

Hawke: the Prime Minister

book reviews the Left, especially Ian Buruma Hawke: The Prime Minister from the float strengthened, but and Timothy Garton Ash, treat By Blanche d’Alpuget for d’Alpuget only Hawke can Ramadan highly positively, yet Melbourne University Press, take credit. denigrate more liberal Muslim 2010 d’Alpuget barely covers the figures—especially the Somali-born $44.95, 401 pages deregulation of the banking sector Dutch citizen Ayaan Hirsi Ali. ISBN 9780522856705 or Keating’s role in putting together Berman’s outrage and anger begins the detail of the policy together, to burn through as he demonstrates awke: The Prime Minister underplaying his contribution to their subtle condescension, their Hhas been written to confirm the government from the start. arguable sexism, their dismissal the ‘great man’ view of history, Hawke’s great contribution as a of her ideas, and their absurd which is not surprising given Labor leader, aside from winning efforts to paint Hirsi Ali as an Blanche d’Alpuget is Bob Hawke’s four elections, was the Accord. In ‘enlightenment fundamentalist.’ current wife. The result this landmark change In the end, this final burst of is that Hawke’s judgment for labour relations in white heat is illuminating. is depicted as near Australia, the major Berman demonstrates that what peerless and he is seen as unions and the Hawke Western intellectuals are doing having full ownership of government agreed to is in fact adopting the categories the reform legacy of his arbitrated wage increases of the Islamist movement governments. It would that were lower than rises themselves—to whom Qaradawi have been a better book if in inflation in exchange is an orthodox moderate and it were less cavalier in its for social benefits such Ramadan is half-way lost to portrayal of Hawke and as universal health care, Western liberalism while Hirsi Ali more willing to credit superannuation, and tax is ‘an infidel fundamentalist,’ as she his team of ministers for reforms benefiting low- was labelled by the murderer of her successes. -

Paul Keating Wheeler Centre

Conversation between Robert Manne and Paul Keating Wheeler Centre Robert Manne Well, thank you very much … [laughter] Paul Keating I knew I was with a popular guy Robert. Robert Manne I’ll speak about what’s just happened towards the end of today. I have to say, we’ve just heard four musicians from the Australian National Academy of Music, performing Wolf’s Italian Serenade. On violins we had Edwina George and Simone Linley Slattery, on viola Laura Curotta and cello Anna Orzech. The reason we heard them was the Australian National Academy of Music was born out of the vision of Paul Keating, its creation being a major component of his government’s 1994 Creative Nation Policy. [applause] Paul I have to say it is my greatest pleasure and privilege to be invited to do this. Paul Keating Thank you Robert. Robert Manne I hope by the end of my questions, the reason for me saying that will be clear. But anyhow, it’s from the bottom of my heart. Paul Keating Thank you for doing it. You are the best one to do it. [laughter] Robert Manne But I’m going to make sure that it’s not entirely comfortable for either of us, so we want to have a rough and tumble time as well. The reason for this conversation is that Paul Keating has produced what I think is a highly agreeable, highly stimulating and I think vividly and beautifully written book and I recommend it to you. It’s a book with a lot in it, a lot in it, just things that struck me, which I won’t be questioning Paul about, but things that struck me – there is for example an extremely moving eulogy for the musical genius Geoffrey Tozer. -

Foreign Investment Review Board Annual Report 2006-07

Appendix B Legislation and regulations, media releases and policy statements and publications Legislation and regulations, media releases and policy statements and publications Legislation and regulations Current 1. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Act No. 92 of 1975 as amended: see Appendix D) 2. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Regulations 1989 (Statutory Rules No. 177 of 1989 as amended: see Appendix E) 3. Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers (Notices) Regulations (Statutory Rules No. 226 of 1975 as amended: see Appendix E) Historical 1. Companies (Foreign Take-overs) Act 1973, No. 199 of 1973 — December 1973. 2. Companies (Foreign Take-overs) Act 1972, No. 134 of 1972 — November 1972. 89 Foreign Investment Review Board Annual Report 2006-07 Media releases and policy statements 1. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Wayne Swan MP — Release of a set of principles to enhance the transparency of Australia’s foreign investment screening regime — 17 February 2008. 2. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Foreign Investment Proposal: Red Earth Holdings b.v. — Acquisition of an additional interest in PBL Media Holdings Pty Limited and the PBL Media Holdings Trust — 4 September 2007. 3. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Foreign Investment: Canwest Global Communications Corp — Acquisition of interest in Ten Network Holdings Limited — 20 August 2007. 4. Statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP — Reappointment of Chairman of Foreign Investment Review Board [Mr John Phillips AO] — 18 April 2007. 5. Joint statement by the Treasurer, The Hon Peter Costello MP, and the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Transport and Regional Services, The Hon Mark Vaile MP — Qantas Airways Ltd — 6 March 2007. -

“Wrong, Or at Best Misleading”: Public Policy and the Slow Recovery in Australia, 1990 – 1994 Joshua Black, the Australian National University

“Wrong, or at Best Misleading”: Public Policy and the Slow Recovery in Australia, 1990 – 1994 Joshua Black, The Australian National University When the Australian economy entered its first recession for nearly thirty years in 2020, many pundits recalled their experiences of the previous downturn, the one that the then-Treasurer declared that we “had to have”. People remembered the “stubbornly high unemployment”, or the “jobless recovery”, and recalled their own experiences as “very tight”.1 Indeed, unemployment breached 11 per cent in July 1992 and was still at 9.2 per cent when the 1996 census was taken.2 To a profound extent, this was both a slow recovery and a jobless one. Why was the recovery so slow and painful for those who experienced it? Earlier commentary emphasised the role of monetary policy and the official cash rate, as if a few earlier movements on the way up or down could have changed “the main outlines of the boom and bust”.3 In this paper, I argue that the whole framework of economic policy that shaped the government’s response to the recession – a framework born out of the neoliberal 1980s – was built on flawed assumptions. First, the Hawke Government’s approach to macroeconomic management was limited by its obsession with (understandably) inflation and (less understandably) the current account deficit. These were the prime objectives of economic policy in the lead-up to the recession, fundamentally constraining policy options. Second, the government acted on the seemingly untenable assumption that employment growth would -

Download Chapter (PDF)

ADDENDA All dates are 1994 unless stated otherwise EUROPEAN UNION. Entry conditions for Austria, Finland and Sweden were agreed on 1 March, making possible these countries' admission on 1 Jan. 1995. ALGERIA. Mokdad Sifi became Prime Minister on 11 April. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA. At the elections of 8 March the Antigua Labour Party (ALP) gained 11 seats. Lester Bird (ALP) became Prime Minister. AUSTRALIA. Following a reshuffle in March, the Cabinet comprised: Prime Minis- ter, Paul Keating; Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Housing and Regional Development, Brian Howe; Minister for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the Govern- ment in the Senate, Gareth Evans; Trade, Bob McMullan; Defence, Robert Ray; Treasurer, Ralph Willis; Finance and Leader of the House, Kim Beazley; Industry, Science and Technology, Peter Cook; Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Nick Bolkus; Employment, Education and Training, Simon Crean; Primary Industries and Energy, Bob Collins; Social Security, Peter Baldwin; Industrial Relations and Transport, Laurie Brereton; Attorney-General, Michael Lavarch; Communications and the Arts and Tourism, Michael Lee; Environment, Sport and Territories, John Faulkner; Human Services and Health, Carmen Lawrence. The Outer Ministry comprised: Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Robert Tickner; Special Minister of State (Vice-President of the Executive Council), Gary Johns; Develop- ment Co-operation and Pacific Island Affairs, Gordon Bilney; Veterans' Affairs, Con Sciacca; Defence Science and Personnel, Gary Punch; Assistant Treasurer, George Gear; Administrative Services, Frank Walker; Small Businesses, Customs and Construction, Chris Schacht; Schools, Vocational Education and Training, Ross Free; Resources, David Beddall; Consumer Affairs, Jeannette McHugh; Justice, Duncan Kerr; Family Services, Rosemary Crowley. -

Hawke: Getting Relaxed and Comfortable with the People’S Philanderer

Hawke: Getting relaxed and comfortable with the people’s philanderer Issue 12, August 2010 | Andrew Thackrah It is a challenging task to convert the nuts and bolts of public policy implementation into engaging history, let alone gripping television drama. Kevin Rudd’s brief Prime Ministership, after all, reminds us that “we campaign in poetry, but we govern in prose”. In the slogan- dominated 2010 election, the main players appeared to have dropped all pretence of passion entirely. The makers of the telemovie Hawke – directed by Emma Freeman and screened recently on the Ten Network – are thus to be commended for attempting to bring the achievements of Australia’s 23rd Prime Minister, Robert James Lee Hawke, to popular attention. Hawke’s blokey charm and tendencies to self-delusion are ably captured by Richard Roxburgh, while Felix Williamson perfects small Keating mannerisms such as the slight licking of lips. Rachael Blake masters an air of sad detachment that the makers seemingly thought appropriate in a portrayal of the protagonist’s first wife, Hazel Hawke. There, however, the pleasures of Hawke end. In an effort to link Labor’s fortunes with the at times tormented and famously emotional personality of Hawke, the filmmakers avoid any serious attempt at highlighting how politics, at its best, is animated by ideas. They take the maxim that the personal is political and deciding that Hawke is a fundamentally decent, though transparently flawed, bloke – the people’s philanderer – are content to leave it at that. Even with these modest ambitions Hawke makes some odd turns along the way. -

Labor Must Risk Offence for Fierce, Honest Debate the AUSTRALIAN

5/27/2019 Labor must risk offence for fierce, honest debate THE AUSTRALIAN Labor must risk offence for fierce, honest debate NOEL PEARSON By NOEL PEARSON, COLUMNIST 12:00AM MAY 25, 2019 • H 209 COMMENTS After spending more than a decade after 1996 disavowing the legacy of Bob Hawke and Paul Keat ing, the Labor Party tentatively came around to invoking the reform heritage of the governments they led from 1983 to 1996. Though the country was entering its third decade of uninterrupted growth since the 1991 recession — a testament to the economic reforms that underpinned this stupendous achievement — their names became the byword for reform only after conservative politicians and commentators used them to contrast and criticise Hawke and Keating’s successors. In recent years Labor came to own Hawke-Keating but it was too late — the reform mantle abandoned in 1996 had been taken up with alacrity by John Howard, and a succession of Labor leaders in opposition and government could not pick up the mantle again. Indeed, they showed no great anxi ety for its loss to the conservatives. The latest Labor contender for the prime ministership cast himself and his agenda for government as falling within the Hawke-Keating tradition, but he was not and his agenda was a far cry from it. Bill Shorten was no ideological heir to the most successful Labor governments in history, and failed miserably as a result. It wasn’t only a matter of disowning the reform mantle; it was the shift from the centre that took place under Kim Beazley as opposition leader and continued until Shorten’s demise last weekend.