Conspiracy Against the Public - an Experiment on Collusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 202 (2019) 87–92

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 202 (2019) 87–92 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Drug and Alcohol Dependence journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugalcdep Evidence for essential unidimensionality of AUDIT and measurement invariance across gender, age and education. Results from the WIRUS study T ⁎ Jens Christoffer Skogena,b,c, , Mikkel Magnus Thørrisend, Espen Olsene, Morten Hessef, Randi Wågø Aasc,d a Department of Health Promotion, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway b Alcohol & Drug Research Western Norway, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway c Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway d Department of Occupational Therapy, Prosthetics and Orthotics, Faculty of Health Sciences, OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway e UiS Business School, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway f Centre for Alcohol and Drug Research, Aarhus University, Denmark ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: Globally, alcohol use is among the most important risk factors related to burden of disease, and Alcohol screening commonly emerges among the ten most important factors. Also, alcohol use disorders are major contributors to AUDIT global burden of disease. Therefore, accurate measurement of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems is im- Factor analysis portant in a public health perspective. The Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) is a widely used, brief ten- Measurement invariance item screening instrument to detect alcohol use disorder. Despite this the factor structure and comparability Work life across different (sub)-populations has yet to be determined. Our aim was to investigate the factor structure of the Sociodemographics AUDIT-questionnaire and the viability of specific factors, as well as assessing measurement invariance across gender, age and educational level. -

Fragmentering Eller Mobilisering? Regional Utvikling I Nordvest Er Temaet for Denne Antologien Basert På Artikler Presentert På Fjordkonferansen 2014

Regional utvikling i Nordvest Fragmentering eller mobilisering? Regional utvikling i Nordvest er temaet for denne antologien basert på artikler presentert på Fjordkonferansen 2014. Mye har endret seg på Nordvestlandet det siste året, og forslag til flere større regionalpolitiske reformer skaper stort engasjement og intens debatt. Blant annet gjelder dette områder knyttet til samarbeid, koordinering og sammenslåinger Fragmentering eller mobilisering? av politidistrikt, byer og tettsteder, høyskoler og sykehus. Parallelt med disse politiske endringene har en halvering av oljeprisen og stenging av viktige eksportmarkeder for fisk gitt skremmeskudd til næringslivet Regional utvikling i Nordvest i regionen. Dette gjør at innovasjonsevnen blir enda viktigere i tiden framover. Viktige hindringer for innovasjon i regionale Fjordantologien 2014 innovasjonssystem kan være fragmentering (mangel på samarbeid og koordinering), «lock-in» (manglende læringsevne) og «institutional thinness» (mangel på spesialiserte kunnskapsaktører).Det er derfor Redaktørar: all grunn til å stille seg spørsmålet om hvilken retning utvikling Øyvind Strand på Nordvestlandet tar: går det mot regional fragmentering eller Erik Nesset regional mobilisering? Er Nordvestlandet fremdeles «liv laga»? Disse Harald Yndestad spørsmålene blir reist både direkte og indirekte i mange av artiklene i årets antologi. Fokuset for Fjordkonferansen er faglig utvikling med mottoet «av fagfolk for fagfolk». Formålet er å være en arena for utveksling av kunnskap og erfaringer, bidra til nettverksbygging mellom fagmiljøene i regionen og stimulere til økt publisering av vitenskapelige artikler fra kunnskapsinstitusjonene i Sogn og Fjordane og Møre og Romsdal. Fjordantologien 2014 Fjordantologien Fjordkonferansen ble arrangert i Loen 19. – 20. juni 2014, med regional utvikling som det samlende temaet. Det var 29 foredrag på programmet, og av disse hadde 26 en forskningbasert karakter. -

Utku Ali Riza Alpaydin.Pdf (1.050Mb)

University-Industry Collaborations (UICs): A Matter of Proximity Dimensions? by UTKU ALİ RIZA ALPAYDIN Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) PhD programme in Social Sciences UiS Business School 202 University of Stavanger NO-4036 Stavanger NORWAY www.uis.no ©202 Utku Ali Rıza Alpaydın ISBN: 978-82-7644-991-4 ISSN: 1890-1387 PhD: Thesis UiS No. 576 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank the members of my supervisor team, Rune Dahl Fitjar and Christian Richter Østergaard. Thank you to my main supervisor, Rune, for all your help and support during this PhD. I have truly appreciated your irreplaceable academic assistance through your insightful comments. You have been a source of a professional and intellectual guidance for my research. Your encouragement to follow my ideas and assistance to support me on every step in the best possible way substantially facilitated my PhD life. I am grateful for your generosity to share your experiences and for your dedication to review all the papers included in this thesis. Thank you to my co-supervisor, Christian, for your contributions on this PhD especially during my term as a visiting scholar at Aalborg University. The suggestions you provided strengthened significantly the empirical part of this thesis. The papers in this PhD have been presented at a wide range of conferences. I would like to thank the organizers, discussants and participants at the following conferences: The 12th Regional Innovation Policies (RIP) Conference, in Santiago del Compostela, Spain, in October 2017; The 16th Triple Helix Conference, in Manchester, United Kingdom, in September 2018; Norwegian Research School on Innovation (NORSI) Conference, in Oslo, Norway, in January 2019; University-Industry Interaction (UIIN) Conference, in Helsinki, Finland, in June 2019; Technology Transfer Society (T2S) Annual Conference, in Toronto, Canada, in September 2019; and The 5th Geography of Innovation (GEOINNO) Conference, in Stavanger, Norway, in January 2020. -

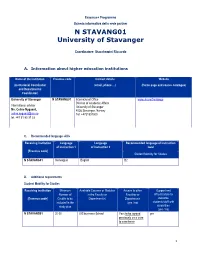

N STAVANG01 University of Stavanger

Erasmus+ Programme Scheda informativa della sede partner N STAVANG01 University of Stavanger Coordinatore: Stacchezzini Riccardo A. Information about higher education institutions Name of the institution Erasmus code Contact details Website (Institutional Coordinator (email, phone …) (Home page and course catalogue) and Departmental Coordinator) University of Stavanger N STAVANG01 International Office www.uis.no/frontpage Division of Academic Affairs International advisor University of Stavanger Ms. Celine Nygaard, 4036 Stavanger. Norway [email protected] Tel. +4751831000 tel. +47 51 83 37 33 C. Recommended language skills Receiving institution Language Language Recommended language of instruction of instruction 1 of instruction 2 level [Erasmus code] Student Mobility for Studies N STAVANG01 Norwegian English B2 D. Additional requirements Student Mobility for Studies Receiving institution Minimum Available Courses or Modules Access to other Support and Number of in the Faculty or Faculties or infrastructure to [Erasmus code] Credits to be Department(s) Departments welcome included in the (yes / no) students/staff with study plan disabilities (yes / no) N STAVANG01 20-30 UIS business School Yes (to be agreed yes previously on a case to case basis 1 N STAVANG01 For information on UiS’ services for mobile participants with special needs/disabilities, please see this web page: http://www.uis.no/studies/practical-information/additional-needs/ E. Calendar Receiving Autumn term Spring term institution APPLICATION DEADLINE APPLICATION DEADLINE -

Norsk Bokfortegnelse / Norwegian National Bibliography Nyhetsliste / List of New Books

NORSK BOKFORTEGNELSE / NORWEGIAN NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY NYHETSLISTE / LIST OF NEW BOOKS Utarbeidet ved Nasjonalbiblioteket Published by The National Library of Norway 2015: 06 : 1 Alfabetisk liste / Alphabetical bibliography Registreringsdato / Date of registration: 2015.06.01-2015.06.14 100 inspirerende mønster til å fargelegge selv Dahlström, Pontus, 1970- Kreativitet og mindfulness : fargelegging som gir ro i sjelen / [idé og prosjektledelse: Alexandra Lidén ; formgivning, billedresearch og billedbearbeiding: Eric Thunfors ; tekst: Pontus Dahlström]. - [Oslo] : Cappelen Damm faktum, 2015. - 2 b. : ill. ; 26 cm. Originaltittel: Kreativitet och mindfulness. - 100 inspirerende mønster til å fargelegge selv. 2015. - [118] s. Originaltittel: 100 bilder på inspirerande mönster att färglägga själv. ISBN 978-82-02-48360-9 (ib.) Dewey: 100 mønstre av planter og dyr til å fargelegge selv Dahlström, Pontus, 1970- Kreativitet og mindfulness : fargelegging som gir ro i sjelen / [idé og prosjektledelse: Alexandra Lidén ; formgivning, billedresearch og billedbearbeiding: Eric Thunfors ; tekst: Pontus Dahlström]. - [Oslo] : Cappelen Damm faktum, 2015. - 2 b. : ill. ; 26 cm. Originaltittel: Kreativitet och mindfulness. - 100 mønstre av planter og dyr til å fargelegge selv. 2015. - [120] s. Originaltittel: 100 bilder på växter och djur att färglägga själv. ISBN 978-82-02-48366-1 (ib.) Dewey: [5. trinn] Salto / [bilderedaktør: Kari Anne Hoen]. - Bokmål[utg.]. - [Oslo] : Gyldendal undervisning, 2013- . - b. : ill. Norsk for barnetrinnet. - [5. trinn] / Marianne Teigen ... [et al.]. 2015- . - b. Tittel laget av katalogisator. Dewey: [6. trinn] Ordriket 1-7 / Christian Bjerke ... [et al.]. - Nynorsk[utg.]. - Bergen : Fagbokforl., 2013- . - b. : ill. For lærerveiledninger, se bokmålutg. Tittel hentet fra omslaget. Dewey: 1 Abdel-Samad, Hamed 1972-: Den islamske fascismen Abdel-Samad, Hamed, 1972- Den islamske fascismen / Hamed Abdel-Samad ; oversatt av Lars Rasmussen Brinth og Christian Skaug. -

2008 Annual Report of Finansmarkedsfondet

Report for Finansmarkedsfondet: Conference on Frontiers of Corporate Finance Organizers: Bernt Arne Ødegaard and Lorán Chollete June 20, 2013 This document summarizes the Conference on Frontiers of Corporate Finance. We approach this report in 3 steps: summary of activities; benefits to Norway and Finansmarkedsfondet, and evaluation. 1. Summary The Conference on Frontiers of Corporate Finance was held on June 13-14, 2013. The conference program is in the attached file.1 The keynote speakers were Professors Espen Eckbo from Dartmouth College, http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/espen.eckbo/ , and David Yermack from New York University, http://people.stern.nyu.edu/dyermack/ . Both professors are internationally renowned experts in the field of corporate finance, and Directors of important Centers for Corporate Governance at their universities. This was the first time that both keynote speakers attended the same conference in Norway. The conference was motivated by outstanding challenges in corporate finance research, as well as the practical issue of understanding the exploding salaries for CEOs in North America and Western Europe versus the more sedate salary growth in Scandinavia. In particular, such rapidly increasing salaries may have been partially funded by excessively risky investments, hence precipitating the recent financial crisis. Moreover, large CEO salaries exacerbate the wealth inequality that plagues much of the global economy. We were privileged to receive participation from both Norwegian and international researchers. Norwegian participants included colleagues from the University of Bergen, University of Stavanger, and Norwegian School of Business (BI). International participants attended from City University of New York, Copenhagen Business School, Dartmouth College, Fordham University, Hunter College, and New York University. -

111E549e10f30b165f86a6e925f

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/1462-6004.htm JSBED 26,5 Motivation of female entrepreneurs: a cross-national study 684 Marina Solesvik Nord University Business School, Nord University, Bodø, Norway Received 8 October 2018 Revised 4 December 2018 Tatiana Iakovleva 11 December 2018 Accepted 12 December 2018 UiS Business School, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway, and Anna Trifilova National Research University Higher School of Economics, Nizhnij Novgorod, Russian Federation Abstract Purpose – This paper focuses on the motivation of females to start businesses in developed and emerging economies. Although the issues related to the motivation of entrepreneurs have been widely studied, there are a few studies focusing on the differences in women’s entrepreneurial motivation in countries with different levels of market economy development. Furthermore, existing studies on female founders mainly adapt the concepts that have often been developed in male-dominated paradigm. The purpose of this paper is to explore in depth motivations of female entrepreneurs in different contexts and discover the dissimilarities in women’s entrepreneurial motivations in countries with different levels of economic development. Design/methodology/approach – The qualitative research approach is applied in this study to explore the social-driven and profit-driven motives of female entrepreneurs. The authors have employed purposeful sampling to select cases. The authors investigated the motivations of 45 female entrepreneurs in Norway (12), Russia (21) and Ukraine (12). Semi-structured interviews were used to collect primary data. The authors have also triangulated the data collected from interviews with the data available on the internet, company reports and newspaper publications. -

Feedback and Performance: Experiments in Behavioral Economics

Feedback and Performance: Experiments in Behavioral Economics by William Gilje Gjedrem Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) Faculty of Social Sciences UiS Business School 2016 University of Stavanger N-4036 Stavanger NORWAY www.uis.no ©2016 William Gilje Gjedrem ISBN: 978-82-7644-685-2 ISSN: 1890-1387 PhD thesis no. 321 Preface This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Philosophiae Doctor (PhD) at the University of Stavanger, Faculty of Social Sciences, Norway. The project was funded by the Norwegian Research Coun- cil (227004). The financial support from the Norwegian Research Council is gratefully acknowledged. The thesis consists of four separate essays which are summarized in the introduction, including a brief discussion concerning the concept of causality and the use of experiments as an empirical strategy. Chapter 2 is the first essay, which has been written together with Mari Rege. Chapter 3 is my single author essay. Chapter 4 is joint work with Ola Kvaløy. Finally, chapter 5 is written in collaboration with Kristoffer Wigestrand Eriksen and Jon Kristian Heimdal. i ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my warmest gratitude to my supervisor Mari Rege. She has been very important during the four years that I have worked on this thesis, and without her support the bumpy road towards a PhD would certainly have been bumpier. Her encouragement was also influential in my decision to pursue a PhD in the first place. I am also very thankful to my co-supervisor, Ola Kvaløy, for his continued support, the encouraging discussions we have had, and the constructive feedback he has provided. -

Futures Literacy Norway

Futures Literacy Norway Futures Literacy Norway The People and the Organizations Behind Welcome to the UNESCO Futures Literacy Summit Booth of Futures Literacy Norway. Futures Literacy Norway is a loose affiliation of organizations and people using anticipation thinking and practices in research and innovation policy learning and leadership. In this document we present the people and the Futures Literacy Norway is an informal collective organizations behind the network. of researchers, consultants and policy https://futuresliteracynorway.blogspot.com makers involved in innovation and leadership for the future UNESCO 1 FUTURES LITERACY SUMMIT 2020 Futures Literacy Norway The People Elisabeth Gulbrandsen is Special Adviser at the Research Council of Norway (RCN). She is currently engaged with RCN's experiments for developing 3rd generation research and innovation policy or Transformative Innovation Policy (TIP). Whereas earlier generations argued with 'market failure' and 'system failure' to motivate the spending of public money on research and innovation, 3rd generation relates to a failure to engage with the Grand Societal Challenges in constructive ways. She networks internationally to further TIP and has been serving on the governing board of the Transformative Innovation Policy Consortium since its inception in 2016. Before joining RCN she held positions at The Centre for Elisabeth Gulbrandsen from the Research Council of Norway is Technology and Culture, University of Oslo and Luleå actively engaged in the AFINO University of Technology. While working at RCN she has also work. She is also part of Futures been a frequent guest researcher and lecturer at Blekinge Literacy Norway, Photo: RCN Institute of Technology. She holds a doctorate in technoscience studies from Blekinge Institute of Technology. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum vitae Name: Fitjar, Rune Dahl ORCID ID: 0000-0001-5333-2701 Date of birth: 26 November 1979 Nationality: Norwegian Languages: Norwegian (native), English (fluent), Spanish (fluent), German (basic) URL for web site: www.fitjar.net • EDUCATION 2007 PhD in Government Government Department, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), UK PhD Supervisor: Eiko Thielemann 2006 Postgraduate Certificate in Higher Education Teaching and Learning Centre, LSE, United Kingdom 2003 M.Sc in Comparative Politics Government Department, LSE, United Kingdom • CURRENT POSITION(S) 2013 – Professor in Innovation Studies UiS Business School, University of Stavanger, Norway 2009 – Senior Research Scientist (20% from 2013) International Research Institute of Stavanger, Norway • PREVIOUS POSITIONS 2010 – 2013 Associate Professor in Quantitative Research Methods (20%) Department of Media, Culture and Social Sciences, University of Stavanger, Norway 2011 – 2012 Visiting Scholar Department of Urban Planning, Luskin School of Public Affairs, UCLA, United States 2007 – 2008 Research Scientist International Research Institute of Stavanger, Norway 2004 – 2006 Class Teacher Government Department and Methodology Institute, LSE, United Kingdom • SUPERVISION OF GRADUATE STUDENTS AND POSTDOCTORAL FELLOWS 2017 – Marte Cecilie Wilhelmsen Solheim, PostDoc, Employee Learning and Firm Innovation. 2017 – Utku Ali Riza Alpaydin, PhD, Proximities in University-Industry Collaboration. 2017 – Kwadwo Atta-Owusu, PhD, Micro-processes of Academics’ Collaboration Behaviours. 2017 – Jonathan Muringani, PhD, Regional Institutions and Economic Development. 2016 – Silje Haus-Reve, PhD, Diverse Knowledge, Innovation and Productivity. 2015 – Nina Hjertvikrem, PhD, Regional Innovation and Collaboration Networks. 2015 – 2018 Giuseppe Calignano, PostDoc, Clusters, Networks and Innovation Policy. 2013 – 2017 Marte Cecilie Wilhelmsen Solheim, PhD, Diversity and Regional Innovation. 2013 – Additionally: co-supervision of 2 PhD students, main supervision of 6 M.Sc. -

Valuation of Proved Vs. Probable Oil and Gas Reserves

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Misund, Bård; Osmundsen, Petter Article Valuation of proved vs. probable oil and gas reserves Cogent Economics & Finance Provided in Cooperation with: Taylor & Francis Group Suggested Citation: Misund, Bård; Osmundsen, Petter (2017) : Valuation of proved vs. probable oil and gas reserves, Cogent Economics & Finance, ISSN 2332-2039, Taylor & Francis, Abingdon, Vol. 5, Iss. 1, pp. 1-17, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2017.1385443 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/194725 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Misund & Osmundsen, Cogent Economics & Finance (2017), 5: 1385443 https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2017.1385443 FINANCIAL ECONOMICS | RESEARCH ARTICLE Valuation of proved vs. -

THE ROLE of UNIVERSITIES in INNOVATION and REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT: the CASE of ROGALAND REGION Utku Ali Rıza Alpaydın Kwadwo Atta-Owusu Saeed Moghadam Saman Ph.D

THE ROLE OF UNIVERSITIES IN INNOVATION AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT: THE CASE OF ROGALAND REGION Utku Ali Rıza Alpaydın Kwadwo Atta-Owusu Saeed Moghadam Saman Ph.D. Candidates, UiS Business School 20 November 2017 This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 722295. Outline • Introduction • Regional Economic Structure of Rogaland • Literature Review and Theoretical Perspective • The Founding, Educational and Research Impact of UiS • Trajectory of UiS’s Regional Engagement • Discussion and Conclusion • Policy Implications RUNIN: THE CASE OF ROGALAND REGION Alpaydın, Atta-Owusu & Saman, UiS Business School Introduction • Rogaland • The 4th largest region in terms of population • Stavanger; The Oil and Gas Capital of Norway • Ranks the 2nd in terms of GDP per inhabitant • 2nd in terms of patent applications in Norway (16.2% of applications in Norway) • 1st in terms of granted patents in Norway (NIPO, 2017). • University of Stavanger • Origins date back to 1960s with Rogaland District College • 6 faculties, 11 departments, 11,194 students and 1,363 full-time employees RUNIN: THE CASE OF ROGALAND REGION Alpaydın, Atta-Owusu & Saman, UiS Business School Regional Economic Structure of Rogaland 60 Share of GDP • Regional Economic History Share of investments Share of exports • Fisheries and shipbuilding until Share of state revenues 1960s 50 • Turning points: 1962 and 1969 • 1970s: Emergence of the booming economy dependent on 40 38.8 petroleum sector Per cent Per • Resonance of International Oil 30 Sector Developments in 24.7 20.7 Rogaland 20 18.4 • Late 1980s: Unprecedented increase in employment, decline 17.1 11.8 in establishments 10 • 1998 Asian Crisis • 2008 Financial Crisis • 2014 Oil Price Crisis 0 19711973197519771979198119831985198719891991199319951997199920012003200520072009201120132015 Source: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.